Chapter 10: Spires in Late Gothic France

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Carolingian, Romanesque, Gothic

3 periods: - Early Medieval (5th cent. - 1000) - Romanesque (11th-12th cent.) - Gothic (mid-12th-15th cent.) - Charlemagne’s model: Constantine's Christian empire (Renovatio Imperii) - Commission: Odo of Metz to construct a palace and chapel in Aachen, Germany - octagonal with a dome -arches and barrel vaults - influences? Odo of Metz, Palace Chapel of Charlemagne, circa 792-805, Aachen http://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=pwIKmKxu614 -Invention of the uniform Carolingian minuscule: revived the form of book production -- Return of the human figure to a central position: portraits of the evangelists as men rather than symbols –Classicism: represented as roman authors Gospel of Matthew, early 9th cent. 36.3 x 25 cm, Kunsthistorische Museum, Vienna Connoisseurship Saint Matthew, Ebbo Gospels, circa 816-835 illuminated manuscript 26 x 22.2 cm Epernay, France, Bibliotheque Municipale expressionism Romanesque art Architecture: elements of Romanesque arch.: the round arch; barrel vault; groin vault Pilgrimage and relics: new architecture for a different function of the church (Toulouse) Cloister Sculpture: revival of stone sculpture sculpted portals Santa Sabina, Compare and contrast: Early Saint-Sernin, Toulouse, Rome, 422-432 Christian vs. Romanesque France, ca. 1070-1120 Stone barrel-vault vs. timber-roofed ceiling massive piers vs. classical columns scarce light vs. abundance of windows volume vs. space size Saint-Sernin, Toulouse, Roman and Romanesque Architecture France, ca. 1070-1120 The word “Romanesque” (Roman-like) was applied in the 19th century to describe western European architecture between the 10th and the mid- 12th centuries Saint-Sernin, Toulouse, France, ca. 1070-1120 4 Features of Roman- like Architecture: 1. round arches 2. -

Rouen Revisited

105 Chapter 8 Rouen Revisited 8.1 Overview This chapter describes Rouen Revisited, an interactive art installation that uses the tech- niques presented in this thesis to interpret the series of Claude Monet's paintings of the Rouen Cathe- dral in the context of the actual architecture. The chapter ®rst presents the artistic description of the work from the SIGGRAPH '96 visual proceedings, and then gives a technical description of how the artwork was created. 8.2 Artistic description This section presents the description of the Rouen Revisited art installation originally writ- ten by Golan Levin and Paul Debevec for the SIGGRAPH'96 visual proceedings and expanded for the Rouen Revisited web site. 106 Rouen Revisited Between 1892 and 1894, the French Impressionist Claude Monet produced nearly 30 oil paintings of the main facËade of the Rouen Cathedral in Normandy (see Fig. 8.1). Fascinated by the play of light and atmosphere over the Gothic church, Monet systemat- ically painted the cathedral at different times of day, from slightly different angles, and in varied weather conditions. Each painting, quickly executed, offers a glimpse into a narrow slice of time and mood. The Rouen Revisited interactive art installation aims to widen these slices, extending and connecting the dots occupied by Monet's paintings in the multidimensional space of turn-of-the-century Rouen. In Rouen Revisited, we present an interactive kiosk in which users are invited to explore the facËade of the Rouen Cathedral, as Monet might have painted it, from any angle, time of day, and degree of atmospheric haze. -

Viewpoint the Fire at Notre Dame Cathedral

Opinion thestructuralengineer.org Notre-Dame fi re Viewpoint Following the recent fi re at Notre-Dame de Paris, Th e fi re at Professor Jacques Heyman discusses the construction Notre-Dame of the cathedral and considers some of the questions that will arise in agreeing an approach to repair. cathedral The double roof system of the typical Gothic great church – a stone vault surmounted by a timber roof – is both decorative and functional. The steep external roof provides the necessary weatherproofi ng dictated by northern European climates (shallow pitches were used for Greek temples); indeed the stone vault, perhaps cracked and in any case not waterproof, itself needs the protection of the outer roof (in Cyprus, the crusader churches, e.g. Famagusta, hardly need this cover). However, timber burns well, and one function of the stone vault is to provide a Figure 1 Burning timbers were largely fi re-resistant barrier between caught by masonry vaults the outer roof and the church. GETTY There is thus a symbiotic action between the two coverings If, however, there are side of the church; the timber roof "ONE FUNCTION OF THE STONE VAULT IS aisles to the nave and choir, protects the stone vault and TO PROVIDE A FIRE-RESISTANT BARRIER then such buttresses would the church from the weather, obstruct those aisles. Hence and the stone vault protects the BETWEEN THE OUTER ROOF AND THE the thrusts from the high stone church from the potential fi re CHURCH" vaults are collected by the fl ying hazard of the timber roof. buttresses, and ‘fl own’ over the This dual action was very aisles to heavy masonry placed evident in the fi re of 15 April nave, and the (roughly) square the masonry rib vault and the outside the church. -

Virginia Theological Seminary Gothic France: 21-31 May 2021

Virginia Theological Seminary Gothic France: 21-31 May 2021 SAMPLE OF PROGRAM* Day 1: Friday, May 21, 2021 Arrival in Paris on your own Group Welcome Dinner in a restaurant Lodging in a 4 * boutique hotel in the 5th or 6th arrondissement of Paris (Hotel des Saint-Pères or similar) Day 2: Saturday May 22, 2021 Meet your private tour bus and 2 guides at your hotel for a guided day in Paris. Guided visit of the church of St Pierre de Montmartre, one of the oldest extant churches in Paris, and the Sacré Coeur Basilica with its mosaic of Christ in Glory. Lunch on your own in historic Montmartre After lunch, meet your tour bus for a guided visit of the St Denis Basilica to learn about the birth of Gothic architecture Return to the hotel at the end of the day. Dinner on your own Lodging in a 4 * boutique hotel in the 5th or 6th arrondissement of Paris (Hotel des Saint-Pères or similar) Day 3: Sunday, May 23, 2021 Meet your private tour bus and your 2 guides in front of your hotel for a day trip to Chartres. Guided tour of Notre Dame de Chartres Cathedral, a unique example of early gothic architecture, th and its 13 century Labyrinth Group Lunch in a restaurant Free time to explore the town of Chartres Return to Paris with your tour bus at the end of the day Dinner on your own Lodging in a 4 * boutique hotel in the 5th or 6th arrondissement of Paris (Hotel des Saint-Pères or similar) Day 4: Monday, May 24, 2021 Meet your 2 guides at your hotel for a guided day in Paris (transport pass provided) Guided visit of Notre Dame Cathedral (the exterior), an iconic masterpiece of Gothic architecture, ravaged by fire in April 2019. -

Paris, Brittany & Normandy

9 or 12 days PARIS, BRITTANY & NORMANDY FACULTY-LED INTERNATIONAL PROGRAMS ABOUT THIS TOUR Rich in art, culture, fashion and history, France is an ideal setting for your students to finesse their language skills or admire the masterpieces in the Louvre. Delight in the culture of Paris, explore the rocky island commune of Mont Saint-Michel and reflect upon the events that took place during World War II on the beaches of Normandy. Through it all, you’ll return home prepared for whatever path lies ahead of you. Beyond photos and stories, new perspectives and glowing confidence, you’ll have something to carry with you for the rest of your life. It could be an inscription you read on the walls of a famous monument, or perhaps a joke you shared with another student from around the world. The fact is, there’s just something transformative about an EF College Study Tour, and it’s different for every traveler. Once you’ve traveled with us, you’ll know exactly what it is for you. DAY 2: Notre Dame DAY 3: Champs-Élysées DAY 4: Versailles DAY 5: Chartres Cathedral DAY 3: Taking in the views from the Eiff el Tower PARIS, BRITTANY & NORMANDY 9 or 12 days Rouen Normandy (2) INCLUDED ON TOUR: OPTIONAL EXCURSION: Mont Saint-Michel Caen Paris (4) St. Malo (1) Round-trip airfare Versailles Chartres Land transportation Optional excursions let you incorporate additional Hotel accommodations sites and attractions into your itinerary and make the Light breakfast daily and select meals most of your time abroad. Full-time Tour Director Sightseeing tours and visits to special attractions Free time to study and explore EXTENSION: French Riviera (3 days) FOR MORE INFORMATION: Extend your tour and enjoy extra time exploring your efcollegestudytours.com/FRAA destination or seeing a new place at a great value. -

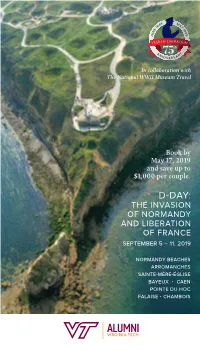

2019 Flagship Vatech Sept5.Indd

In collaboration with The National WWII Museum Travel Book by May 17, 2019 and save up to $1,000 per couple. D-DAY: THE INVASION OF NORMANDY AND LIBERATION OF FRANCE SEPTEMBER 5 – 11, 2019 NORMANDY BEACHES ARROMANCHES SAINTE-MÈRE-ÉGLISE BAYEUX • CAEN POINTE DU HOC FALAISE • CHAMBOIS NORMANDY CHANGES YOU FOREVER Dear Alumni and Friends, Nothing can match learning about the Normandy landings as you visit the ery places where these events unfolded and hear the stories of those who fought there. The story of D-Day and the Allied invasion of Normandy have been at the heart of The National WWII Museum’s mission since they opened their doors as The National D-Day Museum on June 6, 2000, the 56th Anniversary of D-Day. Since then, the Museum in New Orleans has expanded to cover the entire American experience in World War II. The foundation of this institution started with the telling of the American experience on D-Day, and the Normandy travel program is still held in special regard – and is considered to be the very best battlefield tour on the market. Drawing on the historical expertise and extensive archival collection, the Museum’s D-Day tour takes visitors back to June 6, 1944, through a memorable journey from Pegasus Bridge and Sainte-Mère-Église to Omaha Beach and Pointe du Hoc. Along the way, you’ll learn the timeless stories of those who sacrificed everything to pull-off the largest amphibious attack in history, and ultimately secured the freedom we enjoy today. Led by local battlefield guides who are experts in the field, this Normandy travel program offers an exclusive experience that incorporates pieces from the Museum’s oral history and artifact collections into presentations that truly bring history to life. -

The Dual Language of Geometry in Gothic Architecture: the Symbolic Message of Euclidian Geometry Versus the Visual Dialogue of Fractal Geometry

Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture Volume 5 Issue 2 135-172 2015 The Dual Language of Geometry in Gothic Architecture: The Symbolic Message of Euclidian Geometry versus the Visual Dialogue of Fractal Geometry Nelly Shafik Ramzy Sinai University Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.kenyon.edu/perejournal Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons Recommended Citation Ramzy, Nelly Shafik. "The Dual Language of Geometry in Gothic Architecture: The Symbolic Message of Euclidian Geometry versus the Visual Dialogue of Fractal Geometry." Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture 5, 2 (2015): 135-172. https://digital.kenyon.edu/perejournal/vol5/iss2/7 This Feature Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Art History at Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture by an authorized editor of Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ramzy The Dual Language of Geometry in Gothic Architecture: The Symbolic Message of Euclidian Geometry versus the Visual Dialogue of Fractal Geometry By Nelly Shafik Ramzy, Department of Architectural Engineering, Faculty of Engineering Sciences, Sinai University, El Masaeed, El Arish City, Egypt 1. Introduction When performing geometrical analysis of historical buildings, it is important to keep in mind what were the intentions -

The Digital Nature of Gothic

The Digital Nature of Gothic Lars Spuybroek Ruskin’s The Nature of Gothic is inarguably the best-known book on Gothic architecture ever published; argumentative, persuasive, passionate, it’s a text influential enough to have empowered a whole movement, which Ruskin distanced himself from on more than one occasion. Strangely enough, given that the chapter we are speaking of is the most important in the second volume of The Stones of Venice, it has nothing to do with the Venetian Gothic at all. Rather, it discusses a northern Gothic with which Ruskin himself had an ambiguous relationship all his life, sometimes calling it the noblest form of Gothic, sometimes the lowest, depending on which detail, transept or portal he was looking at. These are some of the reasons why this chapter has so often been published separately in book form, becoming a mini-bible for all true believers, among them William Morris, who wrote the introduction for the book when he published it First Page of John Ruskin’s “The with his own Kelmscott Press. It is a precious little book, made with so much love and Nature of Gothic: a chapter of The Stones of Venice” (Kelmscott care that one hardly dares read it. Press, 1892). Like its theoretical number-one enemy, classicism, the Gothic has protagonists who write like partisans in an especially ferocious army. They are not your usual historians – the Gothic hasn’t been able to attract a significant number of the best historians; it has no Gombrich, Wölfflin or Wittkower, nobody of such caliber – but a series of hybrid and atypical historians such as Pugin and Worringer who have tried again and again, like Ruskin, to create a Gothic for the present, in whatever form: revivalist, expressionist, or, as in my case, digitalist, if that is a word. -

Christian Symbolism Little Books on Art Enamels

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. http://books.google.com Christiansymbolism Mrs.HenryJenner THG UN1YGRSITY Of CALIFORNIA LIBRARY LITTLE BOOKS ON ART GENERAL EDITOR: CYRIL DAVENPORT CHRISTIAN SYMBOLISM LITTLE BOOKS ON ART ENAMELS. By Mrs. Nelson Dawson. With 33 illustrations. MINIATURES. Ancient and Modern. By Cyril Davenport. With 46 illus trations. JEWELLERY. By Cyril Davenport. With 4i illustrations, BOOKPLATES. By Edward Almack, F. S. A. With 42 illustrations. THE ARTS OF JAPAN. By Edward Dillon. With 40 illustrations. ILLUMINATED MSS. By John W. Bradley. With 40 illustrations. CHRISTIAN SYMBOLISM. By Mrs. Henry Jenner. With 40 illustrations. OUR LADY IN ART. By Mrs. Henry Jenner. With 40 illustrations. Frontispieces in color. Each with a Bibliography and Index. Small square 16mo, $1.00 net. A. C. McCluro & Co.. Publishers ' -iTRA lIU'.s t. I' .> m. • -V J CHICAGO A. C. MoCJ,URU & CO. 1910 LITTLE BOOKS ON ART CHRISTIAN SYMBOLISM BY MRS. HENRY JENNER < i WITH 41 ILLUSTRATIONS CHICAGO A. C. McCLURG & CO. 1910 First Published in 1910 Reprinted August 1, 1910 CONTENTS PAGE Introduction xiii CHAPTER I Sacraments and Sacramentals i CHAPTER II The Trinity 21 CHAPTER III The Cross and Passion 46 CHAPTER IV The World of Spirits 64 CHAPTER V The Saints 89 CHAPTER VI The Church 115 CHAPTER VII Ecclesiastical Costume 132 396146 vi CHRISTIAN SYMBOLISM CHAPTER VIII PAGE Lesser Symbolisms 145 CHAPTER IX Old Testament Types 168 Bibliography 177 Index . 181 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS THE LAST JUDGMENT . -

Laon Cathedral • Early Gothic Example with a Plan That Resembles Romanesque

Gothic Art • The Gothic period dates from the 12th and 13th century. • The term Gothic was a negative term first used by historians because it was believed that the barbaric Goths were responsible for the style of this period. Gothic Architecture The Gothic period began with the construction of the choir at St. Denis by the Abbot Suger. • Pointed arch allowed for added height. • Ribbed vaulting added skeletal structure and allowed for the use of larger stained glass windows. • The exterior walls are no longer so thick and massive. Terms: • Pointed Arches • Ribbed Vaulting • Flying Buttresses • Rose Windows Video - Birth of the Gothic: Abbot Suger and St. Denis Laon Cathedral • Early Gothic example with a plan that resembles Romanesque. • The interior goes from three to four levels. • The stone portals seem to jut forward from the façade. • Added stone pierced by arcades and arched and rose windows. • Filigree-like bell towers. Interior of Laon Cathedral, view facing east (begun c. 1190 CE). Exterior of Laon Cathedral, west facade (begun c. 1190 CE). Chartres Cathedral • Generally considered to be the first High Gothic church. • The three-part wall structure allowed for large clerestory and stained-glass windows. • New developments in the flying buttresses. • In the High Gothic period, there is a change from square to the new rectangular bay system. Khan Academy Video: Chartres West Facade of Chartres Cathedral, Chartres, France (begun 1134 CE, rebuilt after 1194 CE). Royal Portals of Chartres Cathedral, Chartres, France (begun 1134 CE, rebuilt after 1194 CE). Nave, Chartres Cathedral, Chartres, France (begun 1134 CE, rebuilt after 1194 CE). -

Gothic Churches in Paris St Gervais Et St Protais Image Matching 3D Reconstruction to Understand the Vaults System Geometry

The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, Volume XL-5/W4, 2015 3D Virtual Reconstruction and Visualization of Complex Architectures, 25-27 February 2015, Avila, Spain GOTHIC CHURCHES IN PARIS ST GERVAIS ET ST PROTAIS IMAGE MATCHING 3D RECONSTRUCTION TO UNDERSTAND THE VAULTS SYSTEM GEOMETRY M.Capone a, , M. Campi b, R. Catuogno c a DiARC Dipartimento di Architettura Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II, [email protected] b DiARC Dipartimento di Architettura Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II, [email protected] c DiARC Dipartimento di Architettura Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II, [email protected] Commission V, WG V/4 KEY WORDS: Structure from Motion, Image Matching, 3D Modeling, Ribbed Vaults, Gothic Flamboyant, 3D reconstruction. ABSTRACT: This paper is part of a research about ribbed vaults systems in French Gothic Cathedrals. Our goal is to compare some different gothic cathedrals to understand the complex geometry of the ribbed vaults. The survey isn't the main objective but it is the way to verify the theoretical hypotheses about geometric configuration of the flamboyant churches in Paris. The survey method's choice generally depends on the goal; in this case we had to study many churches in a short time, so we chose 3D reconstruction method based on image dense stereo matching. This method allowed us to obtain the necessary information to our study without bringing special equipment, such as the laser scanner. The goal of this paper is to test image matching 3D reconstruction method in relation to some particular study cases and to show the benefits and the troubles. -

“Cathedral-Style” Churches

“Cathedral-Style” Churches After the turn of the century, Ukrainian congregations often grew to a size where their small church buildings were impractical. The years from about 1920 to 1940 thus witnessed the construction of many large Ukrainian churches in Manitoba. These were no longer simple log or light wood frame structures like those built by the early settlers. The new churches were more elaborate structures, larger in scale and often more sophisticated in ornamentation; similar in conception to the large Ukrainian Baroque churches like the restored St. Sophia in Kiev, the Church of the Holy Trinity and the Chapel of the Three Saints. Although not technically cathedrals – which are the seats of bishops – these churches are so extraordinary, especially in a rural landscape, that they are frequently called “prairie cathedrals.” Considering the modest nature of the log or wood frame churches examined previously in this study, the large churches designed for Ukrainian Catholic and Ukrainian Orthodox congregations in Manitoba during the 1920s, 30s, 40, and 50s are remarkable. Foremost among these are the Ukrainian Catholic churches designed by Father Philip Ruh. His designs for “cathedral‐style” churches adorn the countryside outside Manitoba from Edmonton, Alberta to St. Catharineʹs, Ontario. Research to date attributes 33 structures to this amazing man. Ruh’s influence also spread to other communities in less direct ways. He was often called upon by various congregations to discuss the designs for new churches and the two main contractors working for Ruh relied on his designs for the churches they built without his supervision. Ruh was prolific and his designs influential.