The Socio-Economic and Cultural Context of the Spread of HIV/AIDS in Botswana

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

B-E.00353.Pdf

© University of Hamburg 2018 All rights reserved Klaus Hess Publishers Göttingen & Windhoek www.k-hess-verlag.de ISBN: 978-3-933117-95-3 (Germany), 978-99916-57-43-1 (Namibia) Language editing: Will Simonson (Cambridge), and Proofreading Pal Translation of abstracts to Portuguese: Ana Filipa Guerra Silva Gomes da Piedade Page desing & layout: Marit Arnold, Klaus A. Hess, Ria Henning-Lohmann Cover photographs: front: Thunderstorm approaching a village on the Angolan Central Plateau (Rasmus Revermann) back: Fire in the miombo woodlands, Zambia (David Parduhn) Cover Design: Ria Henning-Lohmann ISSN 1613-9801 Printed in Germany Suggestion for citations: Volume: Revermann, R., Krewenka, K.M., Schmiedel, U., Olwoch, J.M., Helmschrot, J. & Jürgens, N. (eds.) (2018) Climate change and adaptive land management in southern Africa – assessments, changes, challenges, and solutions. Biodiversity & Ecology, 6, Klaus Hess Publishers, Göttingen & Windhoek. Articles (example): Archer, E., Engelbrecht, F., Hänsler, A., Landman, W., Tadross, M. & Helmschrot, J. (2018) Seasonal prediction and regional climate projections for southern Africa. In: Climate change and adaptive land management in southern Africa – assessments, changes, challenges, and solutions (ed. by Revermann, R., Krewenka, K.M., Schmiedel, U., Olwoch, J.M., Helmschrot, J. & Jürgens, N.), pp. 14–21, Biodiversity & Ecology, 6, Klaus Hess Publishers, Göttingen & Windhoek. Corrections brought to our attention will be published at the following location: http://www.biodiversity-plants.de/biodivers_ecol/biodivers_ecol.php Biodiversity & Ecology Journal of the Division Biodiversity, Evolution and Ecology of Plants, Institute for Plant Science and Microbiology, University of Hamburg Volume 6: Climate change and adaptive land management in southern Africa Assessments, changes, challenges, and solutions Edited by Rasmus Revermann1, Kristin M. -

The Scramble for Land Between the Barokologadi Community and Hermannsburg Missionaries

The Scramble for Land between the Barokologadi Community and Hermannsburg Missionaries Victor MS Molobi https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7824-1048 University of South Africa [email protected] Abstract This article investigates the land claim of the Barokologadi of Melorane, with their long history of disadvantages in the land of their forefathers. The sources of such disadvantages are traceable way back to tribal wars (known as “difaqane”) in South Africa. At first, people were forced to retreat temporarily to a safer site when the wars were in progress. On their return, the Hermannsburg missionaries came to serve in Melorane, benefiting from the land provided by the Kgosi. Later the government of the time expropriated that land. What was the significance of this land? The experience of Melorane was not necessarily unique; it was actually a common practice aimed at acquiring land from rural communities. This article is an attempt to present the facts of that event. There were, however, later interruptions, such as when the Hermannsburg Mission Church became part of the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Southern Africa (ELCSA). Keywords: land claim; church land; Barokologadi; missionary movement; Hermannsburg; Melorane; Lutheran Introduction Melorane is the area that includes the southern part of Madikwe Game Park in the North West Province, with the village situated inside the park. The community of Melorane is known as the Barokologadi of Maotwe, which was forcibly removed in 1950. Morokologadi is a porcupine, which is a totem of the Barokologadi community. The community received their land back on 6 July 2007 through the National Department of Land Affairs. -

The Decline in the Role of Chieftainship in Elections Geoffrey Barei Democracy Research Project University of Botswana

The African e-Journals Project has digitized full text of articles of eleven social science and humanities journals. This item is from the digital archive maintained by Michigan State University Library. Find more at: http://digital.lib.msu.edu/projects/africanjournals/ Available through a partnership with Scroll down to read the article. Pula: Botswana Journal of African Studies, Vol.14 No,1 (2000) The decline in the role of chieftainship in elections Geoffrey Barei Democracy Research Project University of Botswana Abstract This article focuses on three districts of Botswana, namely Central District, Ngwaketse District and Kgatleng District. It argues that as a result of the role played by the institution of chieftainship in elections, certain voting paltems that are discussed in the conceptual framework can be associated with it. The extent to which chieftainship has influenced electoral outcomes varies from one area to another. Introduction Chieftainship was the cornerstone of Botswana's political life, both before and during the colonial era, After independence in 1966 the institution underwent drastic reforms in terms of role, influence and respect Despite the introduction of a series of legislation by the post-colonial government that has curtailed and eroded the power of chiefs, it still plays a crucial role in the lives of ordinary people in rural areas, Sekgoma (1993:413) argues that the reform process that has affected chieftainship so far is irreversible, The government is not under pressure to repeal parts of the Acts that -

1 and Economic Development If He Is Aware That There Is a Lot of Illegal

BOTSWANA NATIONAL ASSEMBLY N O T I C E P A P E R (WEDNESDAY 29TH JULY, 2020) NOTICE OF QUESTIONS (FOR ORAL ANSWER ON TUESDAY 4TH AUGUST, 2020) 1. MR. M. M. PULE, MP. (MOCHUDI EAST): To ask the Minister of Finance (345) and Economic Development if he is aware that there is a lot of illegal border crossing along the Madikwe and Limpopo Rivers due to lack of a crossing point after Sikwane Border Post and is the Ministry planning to establish an official crossing point to facilitate residents of Malolwane, Oliphant Drift, Ramotlabaki and Phala Kampa. 2. MS. T. MONNAKGOTLA, MP. (KGALAGADI NORTH): To ask the Minister (346) for Presidential Affairs, Governance and Public Administration if he will consider improving the Radio Botswana signal coverage in Zutshwa, and further extend the coverage to Ngwatle and Ukhwi settlements. 3. MR. T. B. LUCAS, MP. (BOBONONG): To ask the Minister of (347) Environment, Natural Resources Conservation and Tourism if she would: (i) consider including all wild animals under the compensable species in respect of the danger and damage they cause to farmers, businesses and other entities; (ii) consider introducing market equivalent compensation for damage caused by all wild animals. 4. DR. K. GOBOTSWANG, MP. (SEFHARE-RAMOKGONAMI): To ask the (348) Minister of Local Government and Rural Development if he is aware that there are Headmen of Arbitration in Sefhare- Ramokgonami who have been assessed and cleared for social employment but are still to receive their monthly allowances; and if so, to state: (i) how many are on the waiting list; and (ii) when they will be assisted. -

Social and Economie Change in a Tswana Village

social and economie change in a tswana village k. f. m. kooi j ma n SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC CHANCE IN A TSWANA VILLAGE Kunnie Kooijman AFRIKA - STUDIECENTRUM LEIDEN 11 ABSTRACT This dissertation is a descriptive study of Bokaa, a village of 1976 inhabitants situated in the Kgatleng district of Botswana. Bokaa was selected for an analysis and description of social and economie change since relatively much is known of the Kgatleng of thirty to forty years ago through the justly famous writings of Isaac Schapera and since the village has had relatively much contact with modernizing influences. It was not intended to present' a static picture of a 'before' and an 'after' but rather to isolate the processes of change which have led to the present social structure. By means of historical records, oral tradition and lifehistories it was possible to analyse the major historical processes which have taken place since 1892, the date the village was founded. The social and economie structure of Bokaa today was studied by means of participant observation, a questionnaire, interviewing, the collection of case-studies and genealogies, and the consultation of the relevant literature. The major conclusions of the study are that the corporate groups of the traditional social structure are breaking down and that the growth of individualism has become a significant feature of the society. In economie activities this is apparent because kinship co-operation has largely diappeared and individuals make their own arrangements with the aim of realising the greatest benefit to themselves. In the kinship realm it is noticeable since the coporate unity of the ward, family- group and lineage segment has weakened considerably and since individuals increasingly seek to manipulate their kinship bonds and duties to their own advantage. -

Botswana Semiology Research Centre Project Seismic Stations In

BOTSWANA SEISMOLOGICAL NETWORK ( BSN) STATIONS 19°0'0"E 20°0'0"E 21°0'0"E 22°0'0"E 23°0'0"E 24°0'0"E 25°0'0"E 26°0'0"E 27°0'0"E 28°0'0"E 29°0'0"E 30°0'0"E 1 S 7 " ° 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° " 7 S 1 KSANE Kasane ! !Kazungula Kasane Forest ReserveLeshomo 1 S Ngoma Bridge ! 8 " ! ° 0 0 ' # !Mabele * . MasuzweSatau ! ! ' 0 ! ! Litaba 0 ° Liamb!ezi Xamshiko Musukub!ili Ivuvwe " 8 ! ! ! !Seriba Kasane Forest Reserve Extension S 1 !Shishikola Siabisso ! ! Ka!taba Safari Camp ! Kachikau ! ! ! ! ! ! Chobe Forest Reserve ! !! ! Karee ! ! ! ! ! Safari Camp Dibejam!a ! ! !! ! ! ! ! X!!AUD! M Kazuma Forest Reserve ! ShongoshongoDugamchaRwelyeHau!xa Marunga Xhauga Safari Camp ! !SLIND Chobe National Park ! Kudixama Diniva Xumoxu Xanekwa Savute ! Mah!orameno! ! ! ! Safari Camp ! Maikaelelo Foreset Reserve Do!betsha ! ! Dibebe Tjiponga Ncamaser!e Hamandozi ! Quecha ! Duma BTLPN ! #Kwiima XanekobaSepupa Khw!a CHOBE DISTRICT *! !! ! Manga !! Mampi ! ! ! Kangara # ! * Gunitsuga!Njova Wazemi ! ! G!unitsuga ! Wazemi !Seronga! !Kaborothoa ! 1 S Sibuyu Forest Reserve 9 " Njou # ° 0 * ! 0 ' !Nxaunxau Esha 12 ' 0 Zara ! ! 0 ° ! ! ! " 9 ! S 1 ! Mababe Quru!be ! ! Esha 1GMARE Xorotsaa ! Gumare ! ! Thale CheracherahaQNGWA ! ! GcangwaKaruwe Danega ! ! Gqose ! DobeQabi *# ! ! ! ! Bate !Mahito Qubi !Mahopa ! Nokaneng # ! Mochabana Shukumukwa * ! ! Nxabe NGAMILAND DISTRICT Sorob!e ! XurueeHabu Sakapane Nxai National Nark !! ! Sepako Caecae 2 ! ! S 0 " Konde Ncwima ° 0 ! MAUN 0 ' ! ! ' 0 Ntabi Tshokatshaa ! 0 ° ! " 0 PHDHD Maposa Mmanxotai S Kaore ! ! Maitengwe 2 ! Tsau Segoro -

Kgatleng SUB District

Kgatleng SUB District VOL 5.0 KGATLENG SUB DISTRICT Population and Housing Census 2011 Selected Indicators for Villages and Localities ii i Population and Housing Census 2011 [ Selected indicators ] Kgatleng Sub District Population and Housing Census 2011 [Selected Indicators] Kgatleng Sub District 3 Table of Contents Kgatleng Sub District Population And Housing Census 2011: Selected Indicators For Villages And Localities Preface 3 VOL 5,0 1.0 Background and Commentary 6 1.1 Background to the Report 6 Published by 1.2 Importance of the Report 6 STATISTICS BOTSWANA Private Bag 0024, Gaborone 2.0 Population Distribution 6 Phone: (267)3671300, 3.0 Population Age Structure 6 Fax: (267) 3952201 Email: [email protected] 3.1 The Youth 7 Website: www.cso.gov.bw/cso 3.2 The Elderly 7 4.0 Annual Growth Rate 7 5.0 Household Size 7 COPYRIGHT RESERVED 6.0 Marital Status 8 7.0 Religion 8 Extracts may be published if source is duly acknowledged 8.0 Disability 9 9.0 Employment and Unemployment 9 10.0 Literacy 10 ISBN: 978-99968-429-7-9 11.0 Orphan-hood 10 12.0 Access to Drinking Water and Sanitation 10 12.1 Access to Portable Water 10 12.2 Access to Sanitation 11 13.0 Energy 11 13.1 Source of Fuel for Heating 11 13.2 Source of Fuel for Lighting 12 13.3 Source of Fuel for Cooking 12 14.0 Projected Population 2011 – 2026 13 Annexes 14 iii Population and Housing Census 2011 [ Selected indicators ] Kgatleng Sub District Population and Housing Census 2011 [Selected Indicators] Kgatleng Sub District 1 FIGURE 1: MAP OF KATLENG DISTRICT Preface This report follows our strategic resolve to disaggregate the 2011 Population and Housing Census report, and many of our statistical outputs, to cater for specific data needs of users. -

E-Government and Democracy in Botswana: Observational and Experimental Evidence on the Effects of E-Government Usage on Political Attitudes

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Bante, Jana et al. Working Paper E-government and democracy in Botswana: Observational and experimental evidence on the effects of e-government usage on political attitudes Discussion Paper, No. 16/2021 Provided in Cooperation with: German Development Institute / Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE), Bonn Suggested Citation: Bante, Jana et al. (2021) : E-government and democracy in Botswana: Observational and experimental evidence on the effects of e-government usage on political attitudes, Discussion Paper, No. 16/2021, ISBN 978-3-96021-153-2, Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE), Bonn, http://dx.doi.org/10.23661/dp16.2021 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/234177 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. -

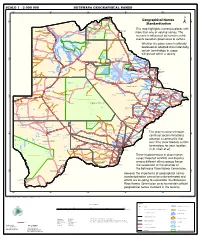

Geographical Names Standardization BOTSWANA GEOGRAPHICAL

SCALE 1 : 2 000 000 BOTSWANA GEOGRAPHICAL NAMES 20°0'0"E 22°0'0"E 24°0'0"E 26°0'0"E 28°0'0"E Kasane e ! ob Ch S Ngoma Bridge S " ! " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° Geographical Names ° ! 8 !( 8 1 ! 1 Parakarungu/ Kavimba ti Mbalakalungu ! ± n !( a Kakulwane Pan y K n Ga-Sekao/Kachikaubwe/Kachikabwe Standardization w e a L i/ n d d n o a y ba ! in m Shakawe Ngarange L ! zu ! !(Ghoha/Gcoha Gate we !(! Ng Samochema/Samochima Mpandamatenga/ This map highlights numerous places with Savute/Savuti Chobe National Park !(! Pandamatenga O Gudigwa te ! ! k Savu !( !( a ! v Nxamasere/Ncamasere a n a CHOBE DISTRICT more than one or varying names. The g Zweizwe Pan o an uiq !(! ag ! Sepupa/Sepopa Seronga M ! Savute Marsh Tsodilo !(! Gonutsuga/Gonitsuga scenario is influenced by human-centric Xau dum Nxauxau/Nxaunxau !(! ! Etsha 13 Jao! events based on governance or culture. achira Moan i e a h hw a k K g o n B Cakanaca/Xakanaka Mababe Ta ! u o N r o Moremi Wildlife Reserve Whether the place name is officially X a u ! G Gumare o d o l u OKAVANGO DELTA m m o e ! ti g Sankuyo o bestowed or adopted circumstantially, Qangwa g ! o !(! M Xaxaba/Cacaba B certain terminology in usage Nokaneng ! o r o Nxai National ! e Park n Shorobe a e k n will prevail within a society a Xaxa/Caecae/Xaixai m l e ! C u a n !( a d m a e a a b S c b K h i S " a " e a u T z 0 d ih n D 0 ' u ' m w NGAMILAND DISTRICT y ! Nxai Pan 0 m Tsokotshaa/Tsokatshaa 0 Gcwihabadu C T e Maun ° r ° h e ! 0 0 Ghwihaba/ ! a !( o 2 !( i ata Mmanxotae/Manxotae 2 g Botet N ! Gcwihaba e !( ! Nxharaga/Nxaraga !(! Maitengwe -

Botswana. Supervisor of Elections. . Report to the Minister of State on the General Elections, 1974

Botswana. Supervisor of Elections. Report to the Minister of State on the general elections, 1974. Gaborone, Government Printer [1974?] / 30p. 29cm. 1. Botswana-Pol. & govt. 2. Elections- Botswana. I • INDEX Page. Report to the Minister of State on the General Elections, 1974 Evaluation and Recommendations *"* Conclusion ...... 2 - • • • • 4 Title Appendix lA' A list of Constituencies, Polling Districts and Polling Stations showing the number of registered voters by constituency and polling station Appendix '/?' Authenticating Officers appointed in accordance with the Presidential Elections (Supplementary Provisions) Act >;• 12 Appendix 'C A list of Returning Officers for the Parliamentary Elections • ! l 13 Appendix Z)' A list of Returning Officers for the Local Government Elections .. ^ . 14 Appendix 'ZT Summary of the Parliamentary election results Appendix lF 17 A list of candidates in the Parliamentary Election showing the number of votes cast for each, number of votes in each constituency, and the majority gained by the winning can- didate and the percentage poll 18 Appendix '6" Summary of Local Government Election results by District or Town Council 20 Appendix 'IT A list of candidates in the Local Government election showing the number of votes cast tor each, the number of voters in each Polling District, the majority gained by the win- ning candidate, and the percentage poll / 22 Appendix T A list of political Parries registered under Section 149 of the Electoral Act 1969 30 Appendix ' J" A Report on-expenditure on the 1974 General Election 30 Sir, REPORT TO ™E MINISTER. OF STATE ON THE GENERAL ELECTIONS, 1974 SSSITOSSS: S.»=^^HS£s~rr?' Lo^l Government Election* become generally available to the public - - - > »S5S^S^as: • l^^sstsss^aSSSS^5^^-^-"5 5. -

I UNIVERSITY of BOTSWANA FACULTY of AGRICULTURE DEPARTMENT of ANIMAL SCIENCE and PRODUCTION MILK PRODUCTION and CAPRINE MASTITIS

UNIVERSITY OF BOTSWANA FACULTY OF AGRICULTURE DEPARTMENT OF ANIMAL SCIENCE AND PRODUCTION MILK PRODUCTION AND CAPRINE MASTITIS OCCURANCE IN THE PRODUCTION STAGE OF THE GABORONE REGION GOAT MILK VALUE CHAIN BY WAZHA MUGABE MASTER OF SCIENCE IN ANIMAL SCIENCE (ANIMAL MANAGEMENT SYSTEMS) JUNE 2015 i UNIVERSITY OF BOTSWANA FACULTY OF AGRICULTURE DEPARTMENT OF ANIMAL SCIENCE AND PRODUCTION MILK PRODUCTION AND CAPRINE MASTITIS OCCURANCE IN THE PRODUCTION STAGE OF THE GABORONE REGION GOAT MILK VALUE CHAIN BY WAZHA MUGABE A dissertation presented in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Science in Animal Science (Animal Management Systems) Main Supervisor: Dr. G.S. Mpapho Co-Supervisors: Prof. J.M. Kamau Prof. S.J Nsoso Dr. W. Mahabile June 2015 ii ABSTRACT T1he first study was initiated with the objectives of analyzing the production stage of the goat milk value chain and prevalence of caprine mastitis and its impact on the value chain. The study was conducted in the Gaborone agricultural region of Botswana. The primary data was collected using a participatory survey from purposefully selected samples of 91 farmers, 4 traders and 220 consumers through self-administered questionnaires. The results show that 88% of the farmers were subsistence orientated meanwhile semi-commercial and commercial farmers constituted 11% and 1 % respectively. A mean milk yield of 1.18L /goat/ per day was produced across farms and this was mostly channeled towards the 88.6% of non-purchasing consumers for home consumption. The average lactation length in the region was 5.37 months, therefore affecting milk consumption and availability patterns. -

Scanned PDF[8.20

Handbook for District Sanitation Coordinators Authors: Kebadire Basaako Ronald D. Parker Robert B. Waller James G. Wilson Editor: John van Nostrand ! L ! G RA R Y, Uï Í E K • ' i AT i O M A L R ¿ F í : ; : íi i\ 0 E ir CCN'VRÎÏ Por? cc v':.'n.;r¡¡¡ v V/AÍÍÍK SUPPLY i AfvT! ¿A; i ) r.o. 93 ;;;o! 2. „•'•;-'' d AD í he '-¡ague t ,1 1 1 i A n T.I. (070) 81 49 11 ext. 1 T 1 / 1 '4 ¿ RN: ño C" l Lop<Q ) LO: N/8- i 1- lo HA 3O2, Washington, DC December 1983 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors wish to acknowledge, with thanks, the advice and assistance of the Council Secretaries and Staff of Kgatleng and Southern Districts, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), and the Technology Advisory Group (TAG) operating under the United Nations Development Programme Interregional Project INT/81/047 (executed by the World Bank). INTRODUCTION TO TAG REPRINT COPY The "Handbook for District Sanitation Coordinators" was originally prepared by two members of the USAID-funded team that had assisted in the development and implementation of the Environmental Sanitation and Protection (ESPP) Pilot Project in Botswana. TAG has been closely involved with ESPP since its inception, through participation in USAID project development missions and through technical support to the Senior Public Health Engineer (SPHE) in the Ministry of Local Government and Lands (MLGL) - an expatriate provided by UNDP through its project BOT/79/003. The SPHE supervised the project. TAG missions and headquarters staff were also responsible for the editing and production of the handbook.