Assessing Maternal Health and Catastrophic Expenditure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Justice & Security Practices, Perceptions, and Problems in Kabul and Nangarhar

Justice & Security Practices, Perceptions, and Problems in Kabul and Nangarhar M AY 2014 Above: Behsud Bridge, Nangarhar Province (Photo by TLO) A TLO M A P P I N G R EPORT Justice and Security Practices, Perceptions, and Problems in Kabul and Nangarhar May 2014 In Cooperation with: © 2014, The Liaison Office. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, recording or otherwise without prior written permission of the publisher, The Liaison Office. Permission can be obtained by emailing [email protected] ii Acknowledgements This report was commissioned from The Liaison Office (TLO) by Cordaid’s Security and Justice Business Unit. Research was conducted via cooperation between the Afghan Women’s Resource Centre (AWRC) and TLO, under the supervision and lead of the latter. Cordaid was involved in the development of the research tools and also conducted capacity building by providing trainings to the researchers on the research methodology. While TLO makes all efforts to review and verify field data prior to publication, some factual inaccuracies may still remain. TLO and AWRC are solely responsible for possible inaccuracies in the information presented. The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed in the report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Cordaid. The Liaison Office (TL0) The Liaison Office (TLO) is an independent Afghan non-governmental organization established in 2003 seeking to improve local governance, stability and security through systematic and institutionalized engagement with customary structures, local communities, and civil society groups. -

Afghanistan State Structure and Security Forces

European Asylum Support Office Afghanistan State Structure and Security Forces Country of Origin Information Report August 2020 SUPPORT IS OUR MISSION European Asylum Support Office Afghanistan State Structure and Security Forces Country of Origin Information Report August 2020 More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu). ISBN: 978-92-9485-650-0 doi: 10.2847/115002 BZ-02-20-565-EN-N © European Asylum Support Office (EASO) 2020 Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, unless otherwise stated. For third-party materials reproduced in this publication, reference is made to the copyrights statements of the respective third parties. Cover photo: © Al Jazeera English, Helmand, Afghanistan 3 November 2012, url CC BY-SA 2.0 Taliban On the Doorstep: Afghan soldiers from 215 Corps take aim at Taliban insurgents. 4 — AFGHANISTAN: STATE STRUCTURE AND SECURITY FORCES - EASO COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION REPORT Acknowledgements This report was drafted by the European Asylum Support Office COI Sector. The following national asylum and migration department contributed by reviewing this report: The Netherlands, Office for Country Information and Language Analysis, Ministry of Justice It must be noted that the review carried out by the mentioned departments, experts or organisations contributes to the overall quality of the report, it but does not necessarily imply their formal endorsement of the final report, which is the full responsibility of EASO. AFGHANISTAN: STATE STRUCTURE AND SECURITY -

Sunday, 06 October 2019 Venue: FAO Meeting Room Draft Agenda

Time: 14:00 – 15:30 hrs Date: Sunday, 06 October 2019 Venue: FAO Meeting Room Draft Agenda: Introduction of ANDMA Nangarhar Newly appointed Director Update on the current humanitarian situation in Nurgal (Kunar) and Surkhrod (Nangarhar) – DoRR, OCHA Petition from Surkhrod for Tents and IDPs left of assessment Update on the status of Joint Needs Assessment & Response – OCHA and Partners Petitions for IDPs from Laghman AOB www.unocha.org The mission of the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) is to mobilize and coordinate effective and principled humanitarian action in partnership with national and international actors. Coordination Saves Lives Update on Assessment & Response on Natural disasters – as of 21 April 2019 - IOM & ANDMA Deaths In Responde Province Districts Affected & Initial Info. # of Families Agencies Agencies Response Assistance Action Points j Status Assessed Families ured Assessed Assessed Responde Provided Affected d d Nangarhar 250 (1817 9 5 250 and 105 IOM, IMC, IOM, Ongoing NFI, Tents, -Health MHT will be deployed Assessment individuals) Assessment ongoing WFP, SCI, effective 23 April 2019.4.22, completed in Lalpur, NCRO, Pending: food, Kama, Rodat, Behsud, OXFAM, -WASH cluster will reassess the Jalalabad city, Goshta, RRD, ARCS, needs and respond accordingly. Mohmandara, Kot, Bati DACAAR, Kot DAIL, DA -IOM to share the list of families recommended for permanent Assessment ongoing: shelter with ACTED. Shirzad, Dehbala, Pachir- Agam, -ANDMA will clarify the land Chaparhar, -

The ANSO Report (16-30 September 2010)

The Afghanistan NGO Safety Office Issue: 58 16-30 September 2010 ANSO and our donors accept no liability for the results of any activity conducted or omitted on the basis of this report. THE ANSO REPORT -Not for copy or sale- Inside this Issue COUNTRY SUMMARY Central Region 2-7 The impact of the elections and Zabul while Ghazni of civilian casualties are 7-9 Western Region upon CENTRAL was lim- and Kandahar remained counter-productive to Northern Region 10-15 ited. Security forces claim extremely volatile. With AOG aims. Rather it is a that this calm was the result major operations now un- testament to AOG opera- Southern Region 16-20 of effective preventative derway in various parts of tional capacity which al- Eastern Region 20-23 measures, though this is Kandahar, movements of lowed them to achieve a unlikely the full cause. An IDPs are now taking place, maximum of effect 24 ANSO Info Page AOG attributed NGO ‘catch originating from the dis- (particularly on perceptions and release’ abduction in Ka- tricts of Zhari and Ar- of insecurity) for a mini- bul resulted from a case of ghandab into Kandahar mum of risk. YOU NEED TO KNOW mistaken identity. City. The operations are In the WEST, Badghis was The pace of NGO incidents unlikely to translate into the most affected by the • NGO abductions country- lasting security as AOG wide in the NORTH continues onset of the elections cycle, with abductions reported seem to have already recording a three fold in- • Ongoing destabilization of from Faryab and Baghlan. -

AFGHANISTAN - Base Map KYRGYZSTAN

AFGHANISTAN - Base map KYRGYZSTAN CHINA ± UZBEKISTAN Darwaz !( !( Darwaz-e-balla Shaki !( Kof Ab !( Khwahan TAJIKISTAN !( Yangi Shighnan Khamyab Yawan!( !( !( Shor Khwaja Qala !( TURKMENISTAN Qarqin !( Chah Ab !( Kohestan !( Tepa Bahwddin!( !( !( Emam !( Shahr-e-buzorg Hayratan Darqad Yaftal-e-sufla!( !( !( !( Saheb Mingajik Mardyan Dawlat !( Dasht-e-archi!( Faiz Abad Andkhoy Kaldar !( !( Argo !( Qaram (1) (1) Abad Qala-e-zal Khwaja Ghar !( Rostaq !( Khash Aryan!( (1) (2)!( !( !( Fayz !( (1) !( !( !( Wakhan !( Khan-e-char Char !( Baharak (1) !( LEGEND Qol!( !( !( Jorm !( Bagh Khanaqa !( Abad Bulak Char Baharak Kishim!( !( Teer Qorghan !( Aqcha!( !( Taloqan !( Khwaja Balkh!( !( Mazar-e-sharif Darah !( BADAKHSHAN Garan Eshkashem )"" !( Kunduz!( !( Capital Do Koh Deh !(Dadi !( !( Baba Yadgar Khulm !( !( Kalafgan !( Shiberghan KUNDUZ Ali Khan Bangi Chal!( Zebak Marmol !( !( Farkhar Yamgan !( Admin 1 capital BALKH Hazrat-e-!( Abad (2) !( Abad (2) !( !( Shirin !( !( Dowlatabad !( Sholgareh!( Char Sultan !( !( TAKHAR Mir Kan Admin 2 capital Tagab !( Sar-e-pul Kent Samangan (aybak) Burka Khwaja!( Dahi Warsaj Tawakuli Keshendeh (1) Baghlan-e-jadid !( !( !( Koran Wa International boundary Sabzposh !( Sozma !( Yahya Mussa !( Sayad !( !( Nahrin !( Monjan !( !( Awlad Darah Khuram Wa Sarbagh !( !( Jammu Kashmir Almar Maymana Qala Zari !( Pul-e- Khumri !( Murad Shahr !( !( (darz !( Sang(san)charak!( !( !( Suf-e- (2) !( Dahana-e-ghory Khowst Wa Fereng !( !( Ab) Gosfandi Way Payin Deh Line of control Ghormach Bil Kohestanat BAGHLAN Bala !( Qaysar !( Balaq -

(SIKA) – East Final Report

Stability in Key Areas (SIKA) – East Final Report ACKU 2 ACKU Ghazni Province_Khwaja Umari District_Qala Naw Girls School Sport Field (PLAY) opening ceremony ii Stability in Key Areas (SIKA) – East Final Report ACKU The authors’ views expressed in this document do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government iii Name of USAID Activity: Afghanistan Stability in Key Areas (SIKA) - East Name of Prime Contractor: AECOM International Development $144,948,162.00 Total funding: Start date: December 7, 2011 Option period: December 3, 2013 End date: September 6, 2015 Geographic locations: Ghazni Province: Andar, Bahrami Shahid, Dih Yak, Khwaja Umari, Qarabagh, and Muqur Khost Province: Gurbuz, Jaji Maidan, Mando Zayi, Tani, and Nadir Shah Kot Logar Province: Baraki Barak, Khoshi, and Mohammad Agha Maydan Wardak Province: Chaki Wardak, Jalrez, Nirkh, Saydabad and Maydan Shahr Paktya Province: Ahmad Abad, Laja Ahmad Khail, Laja Mangal, Zadran, Garda Serai, Zurmat, Ali Khail, Mirzaka, and Sayed Karam Paktika Province: Sharan and Yosuf Khel Overall goals and objectives: SIKA – East promotes stabilization in key areas by supporting GIRoA at the district level, while coordinating efforts at the provincial level to implement community led development and governance initiatives that respond to the population’s needs and concerns to build confidence, promote stability, and increase the provision of basic services. • Address Instability and Respond to Concerns: Provincial and District Entities increasingly address Expected Results: sources of instability and take measures to respond to the population’s development and governance concerns. • Enable Access to Services: Provincial and District entities understand what organizations and provincial line departments work within their geographic areas, ACKUwhat kind of services they provide, and how the population can access those services. -

WKW Creating-New-Spaces-Afghanistan

Women’s Participation in Community Decision-Making Spaces in Afghanistan A Case of Istalif and Kalakan Districts in Kabul Province 2 Women’s Participation in Community Decision-Making Spaces in Afghanistan Acknowledgements Author: Mariam Jalalzada Contributing Partner Organisation: Afghan Women’s Resource Center (AWRC) Design: Dacors Design This research study was made possible by the efforts of the programme staff of the Afghan Women’s Resource Center in Kalakan and Istalif Districts of Kabul Province – especially Samira Aslamzada. Their efforts in organising the field trips, focus group discussions with the women, and interviews with various individuals, is to be lauded. Special thanks are due to Durkhani Aziz for her kindness and her relentless role as co-facilitator during the entire fieldwork, ensuring attendance of Community Development Council (CDC) members and Government officials in the focus group discussions and interviews. My sincere thanks to the CDC members for taking the time and effort to attend the discussions and to talk about their personal lives, and to the Governmental representatives for their helpful engagement with this research. October 2015 3 Women’s Participation in Community Decision-Making Spaces in Afghanistan Contents Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................2 Acronyms............................................................................................................................4 Executive summary ........................................................................................................5 -

The Informal Regulation of the Onion Market in Nangarhar, Afghanistan Working Paper 26 Giulia Minoia, Wamiqullah Mumatz and Adam Pain November 2014 About Us

Researching livelihoods and Afghanistan services affected by conflict Kabul Jalalabad The social life of the Nangarhar Pakistan onion: the informal regulation of the onion market in Nangarhar, Afghanistan Working Paper 26 Giulia Minoia, Wamiqullah Mumatz and Adam Pain November 2014 About us Secure Livelihoods Research Consortium (SLRC) aims to generate a stronger evidence base on how people make a living, educate their children, deal with illness and access other basic services in conflict-affected situations. Providing better access to basic services, social protection and support to livelihoods matters for the human welfare of people affected by conflict, the achievement of development targets such as the Millennium Development Goals and international efforts at peace- building and state-building. At the centre of SLRC’s research are three core themes, developed over the course of an intensive one- year inception phase: . State legitimacy: experiences, perceptions and expectations of the state and local governance in conflict-affected situations . State capacity: building effective states that deliver services and social protection in conflict- affected situations . Livelihood trajectories and economic activity under conflict The Overseas Development Institute (ODI) is the lead organisation. SLRC partners include the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit (AREU), the Centre for Poverty Analysis (CEPA) in Sri Lanka, Feinstein International Center (FIC, Tufts University), Focus1000 in Sierra Leone, Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), -

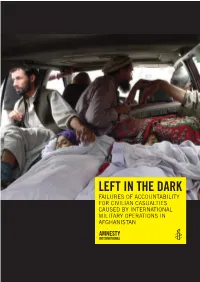

Left in the Dark

LEFT IN THE DARK FAILURES OF ACCOUNTABILITY FOR CIVILIAN CASUALTIES CAUSED BY INTERNATIONAL MILITARY OPERATIONS IN AFGHANISTAN Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 3 million supporters, members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. First published in 2014 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom © Amnesty International 2014 Index: ASA 11/006/2014 Original language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. The copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. To request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Cover photo: Bodies of women who were killed in a September 2012 US airstrike are brought to a hospital in the Alingar district of Laghman province. © ASSOCIATED PRESS/Khalid Khan amnesty.org CONTENTS MAP OF AFGHANISTAN .......................................................................................... 6 1. SUMMARY ......................................................................................................... 7 Methodology .......................................................................................................... -

19 October 2020 "Generated on Refers to the Date on Which the User Accessed the List and Not the Last Date of Substantive Update to the List

Res. 1988 (2011) List The List established and maintained pursuant to Security Council res. 1988 (2011) Generated on: 19 October 2020 "Generated on refers to the date on which the user accessed the list and not the last date of substantive update to the list. Information on the substantive list updates are provided on the Council / Committee’s website." Composition of the List The list consists of the two sections specified below: A. Individuals B. Entities and other groups Information about de-listing may be found at: https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/ombudsperson (for res. 1267) https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/sanctions/delisting (for other Committees) https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/content/2231/list (for res. 2231) A. Individuals TAi.155 Name: 1: ABDUL AZIZ 2: ABBASIN 3: na 4: na ﻋﺒﺪ اﻟﻌﺰﻳﺰ ﻋﺒﺎﺳﯿﻦ :(Name (original script Title: na Designation: na DOB: 1969 POB: Sheykhan Village, Pirkowti Area, Orgun District, Paktika Province, Afghanistan Good quality a.k.a.: Abdul Aziz Mahsud Low quality a.k.a.: na Nationality: na Passport no: na National identification no: na Address: na Listed on: 4 Oct. 2011 (amended on 22 Apr. 2013) Other information: Key commander in the Haqqani Network (TAe.012) under Sirajuddin Jallaloudine Haqqani (TAi.144). Taliban Shadow Governor for Orgun District, Paktika Province as of early 2010. Operated a training camp for non- Afghan fighters in Paktika Province. Has been involved in the transport of weapons to Afghanistan. INTERPOL- UN Security Council Special Notice web link: https://www.interpol.int/en/How-we-work/Notices/View-UN-Notices- Individuals click here TAi.121 Name: 1: AZIZIRAHMAN 2: ABDUL AHAD 3: na 4: na ﻋﺰﯾﺰ اﻟﺮﺣﻤﺎن ﻋﺒﺪ اﻻﺣﺪ :(Name (original script Title: Mr Designation: Third Secretary, Taliban Embassy, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates DOB: 1972 POB: Shega District, Kandahar Province, Afghanistan Good quality a.k.a.: na Low quality a.k.a.: na Nationality: Afghanistan Passport no: na National identification no: Afghan national identification card (tazkira) number 44323 na Address: na Listed on: 25 Jan. -

Afghanistan Security Situation in Nangarhar Province

Report Afghanistan: The security situation in Nangarhar province Translation provided by the Office of the Commissioner General for Refugees and Stateless Persons, Belgium. Report Afghanistan: The security situation in Nangarhar province LANDINFO – 13 OCTOBER 2016 1 About Landinfo’s reports The Norwegian Country of Origin Information Centre, Landinfo, is an independent body within the Norwegian Immigration Authorities. Landinfo provides country of origin information to the Norwegian Directorate of Immigration (Utlendingsdirektoratet – UDI), the Immigration Appeals Board (Utlendingsnemnda – UNE) and the Norwegian Ministry of Justice and Public Security. Reports produced by Landinfo are based on information from carefully selected sources. The information is researched and evaluated in accordance with common methodology for processing COI and Landinfo’s internal guidelines on source and information analysis. To ensure balanced reports, efforts are made to obtain information from a wide range of sources. Many of our reports draw on findings and interviews conducted on fact-finding missions. All sources used are referenced. Sources hesitant to provide information to be cited in a public report have retained anonymity. The reports do not provide exhaustive overviews of topics or themes, but cover aspects relevant for the processing of asylum and residency cases. Country of origin information presented in Landinfo’s reports does not contain policy recommendations nor does it reflect official Norwegian views. © Landinfo 2017 The material in this report is covered by copyright law. Any reproduction or publication of this report or any extract thereof other than as permitted by current Norwegian copyright law requires the explicit written consent of Landinfo. For information on all of the reports published by Landinfo, please contact: Landinfo Country of Origin Information Centre Storgata 33A P.O. -

VOTING TOGETHER Why Afghanistan’S 2009 Elections Were (And Were Not) a Disaster

AFGHANISTAN RESEARCH AND EVALUATION UNIT Briefing Paper Series Noah Coburn and Anna Larson November 2009 VOTING TOGETHER Why Afghanistan’s 2009 Elections were (and were not) a Disaster Overview Contents The Afghan elections in 1. Contextual 2009 have become infamous Background and for low turnout, fraud and Political Landscapes ...2 insecurity. Delay in announcing 2. Voting Blocs. ..........7 the results and rumours of private negotiations have 3. Why Blocs Persist increased existing scepticism and Continue to of the electoral process among Shape Elections .... 10 national and international 4. Conclusions and commentators. What has been Ways Forward ...... 17 overlooked, however, is the way in which—at least at the local level—these elections About the Authors have been used to change the Noah Coburn is a sociocultural balance of power in a relatively anthropologist in Kabul with peaceful manner. In many the United States Institute of areas of Afghanistan, the polls Voters queuing in Qarabagh Peace. He is also a Presidential emphasised local divisions and Fellow at Boston University, groupings, and highlighted the importance of political and voting where he is completing a blocs (which can include ethnic groups, qawms,1 or even family doctoral dissertation on units) in determining political outcomes. Also, while perhaps not local political structures, “legitimate” by international standards, these elections reflected the conflict and democratisation highly localised cultural and social context in which they took place: in Afghanistan. He has a MA a context that is often patronage-based and in which power is gained from Columbia University. through constant struggle and dialogue between political groups and Anna Larson is a Researcher leaders.