WKW Creating-New-Spaces-Afghanistan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Creating a Network of Model Schools to Support the Future Of

‘Creating a Network of Model Schools to Support the Future of Afghanistan’s Children’ An Educational Midline Survey for the Womanity Foundation 1 Samuel Hall is a research and consulting company with headquarters in Kabul, Afghanistan. We specialise in socio-economic surveys, private and public sector studies, monitoring and evaluation and impact assessments for governmental, non-governmental and international organizations. Our teams of field practitioners, academic experts and local interviewers have years of experience leading research in Afghanistan. We use our expertise to balance the needs of beneficiaries with the requirements of development actors. This technique has enabled us to acquire a firm grasp of the political and socio-cultural context of the country along with designing solid data collection methods. Our analyses are used for monitoring, evaluating and planning sustainable programmes as well as to apply cross-disciplinary knowledge and integrated solutions for efficient and effective interventions. Visit us at www.samuelhall.org Photo Credits: Ibrahim Ramazani and Naeem Meer This publication was commissioned by the Womanity Foundation and was prepared and conducted solely by Samuel Hall. The views and analysis contained in the publication therefore do not necessarily represent the views of the Womanity Foundation. This report should be cited using the following referencing style: Samuel Hall 2013, “Creating a Network of Model Schools to Support the Future of Afghanistan’s Children: An Educational Baseline Survey for the Womanity Foundation”. Samuel Hall encourages the dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission to reproduce portions of the work promptly. For permission to photocopy or reprint any part of this work, please send your request, along with complete information, to [email protected]. -

Female Police Officers Were Posi- Antzar, His 25 Colleagues and a Group of Village Elders Participated in a of Her Greatest Life’S Ambitions

United Nations Development Programme The Development Advocate 1 May 2013 EEmpoweredmpowered lives.lives. RResilientesilient nations.nations. AFGHANISTAN EDITION Inside the micro hydroelectric power plant in Kata Qala village. (Joel van Houdt/UNDP) MICRO HYDROELECTRIC POWER LIGHTING UP THE HOMES AND LIVES OF THOUSANDS BY MUJIB MASHAL of micro hydroelectric power plants. that is powering 2,163 households, Borghaso, Bamyan Province — Afghanistan has one of the benefiting more than 15,000 people. WELCOME lowest per capita rates of electricity These plants are not only bringing Eleven-year-old Mohamed Nasim, consumption in the world. In 2007 tangible improvements to the lives who is in sixth grade, wakes up at only seven percent of the population of the people who now depend on 5:30 every morning to take computer had access to electricity, according to them for access to electricity, they lessons in a makeshift classroom here Government data. Since then, that are creating jobs for locals, improving in Borghaso village, Bamyan Province, figure has risen to about 30 percent, relationships with the Government northwest of Kabul. He draws a house thanks to an increase in imported of Afghanistan and providing in Microsoft Paint, colors it, and types electricity and the construction of environmentally-friendly, and thus his name in the corner as his young micro hydroelectric and solar panel sustainable, sources of energy. And teacher watches over his shoulders. stations. But imported electricity, in a country where many people The back of Mohamed’s hands are which provides more than half of depend on kerosene oil, wood and Mr. Ajay Chhibber meets H.E. -

“We Have the Promises of the World”

Afghanistan “We Have the Promises HUMAN of the World” RIGHTS WATCH Women’s Rights in Afghanistan “We Have the Promises of the World” Women’s Rights in Afghanistan Copyright © 2009 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-574-1 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org December 2009 1-56432-574-1 “We Have the Promises of the World” Women’s Rights in Afghanistan Map of Afghanistan ............................................................................................................ 1 I. Summary ......................................................................................................................... 2 Key Recommendations .................................................................................................. 11 II. Methodology ................................................................................................................ 12 III. Attacks on Women in Public Life ...................................................................................14 Women in Public Life in Afghanistan ............................................................................. -

Afghanistan Rule of Law Project

AFGHANISTAN RULE OF LAW PROJECT FIELD STUDY OF INFORMAL AND CUSTOMARY JUSTICE IN AFGHANISTAN AND RECOMMENDATIONS ON IMPROVING ACCESS TO JUSTICE AND RELATIONS BETWEEN FORMAL COURTS AND INFORMAL BODIES Contracted under USAID Contract Number: DFD-I-00-04-00170-00 Task Order Number: DFD-1-800-00-04-00170-00 Afghanistan Rule of Law Project Checchi and Company Consulting, Inc. Afghanistan Rule of Law Project House #959, St. 6 Taimani iWatt Kabul, Afghanistan Corporate Office: 1899 L Street, NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA June 2005 This publication was prepared for the United States Agency for International Development. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION AND STUDY METHODOLOGY .............................................................1 II. BACKGROUND OF INFORMAL AND CUSTOMARY JUSTICE.......................................4 A. Definition and Characteristics..........................................................................................................4 B. Recent Studies...................................................................................................................................6 C. Jirga and Shura..................................................................................................................................7 III. SUMMARY OF FINDINGS AND CONCLUSIONS............................................................9 A. The Informal System ........................................................................................................................9 B. The Formal System.........................................................................................................................12 -

Final Evaluation of the Project for Building Resilience and Self

Project evaluation series Final evaluation of the project for Building Resilience and Self-reliance of Livestock Keepers by Improving Control of Foot-and-Mouth Disease and other Transboundary Animal Diseases in Afghanistan PROJECT EVALUATION SERIES Final evaluation of the project for Building Resilience and Self-reliance of Livestock Keepers by Improving Control of Foot-and- Mouth Disease and other Transboundary Animal Diseases in Afghanistan OSRO/AFG/402/JPN FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Rome, 2019 Required citation: FAO. 2019. Final Evaluation of the Project for Building Resilience and Self-reliance of Livestock Keepers by Improving Control of Foot-and-Mouth Disease and other Transboundary Animal Diseases in Afghanistan. Rome. 8 pp. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO. © FAO, 2019, last updated on 17/09/2021 Some rights reserved. This work is made available under the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo/legalcode/legalcode). -

DAD Afghanistan

Core Development Budget 1389 Provincial Allocation 1389 Province / Gov.Resp.Agency / Project Title Donors Commitment Breakdown (USD) Country-Wide 387,475,503 Afghanistan High Atomic Energy 100,000 Commission AFG/750002 Staff capacity Building Project GoA 100,000 Afghanistan National Standard Authority 600,000 Procurement of laboratories Mines and AFG/580006 GoA 300,000 Lequid Gas in Kabul and in provinces Procurment of Construction Material AFG/580009 GoA 300,000 Laboratory in Kabul Attorney General 719,904 AFG/510003 Offices for Attorney General in Provinces GoA 115,904 Criminal Justice Task Force-Counter AFG/510006 UK-MoFA 604,000 Narcotics (AGO) Control and Audit Office 1,887,000 Construction of new building for Control and AFG/660004 GoA 1,367,000 Audit Office AFG/660014 Support to the budget office of the parliament ARTF 220,000 AFG/660015 Purchasing of office equipemetns WB 300,000 Directorate of Environment 774,000 AFG/600006 Construction of NEPA Centeral Building GoA 474,000 AFG/600009 Laboratory equipment (water Air Soil) GoA 300,000 Geodesy and Cartography Office 537,000 AFG/650004 National Cadastral Survey GoA 35,000 AFG/650008 Geodesy and Cartography Equipment GoA 500,000 AFG/650009 Photogrametry Equipment and Metadata GoA 2,000 Independent Administrative Reform and 9,161,000 Civil Service Commission New, Proposed Management Capacity AFG/620030 GoA,ARTF 5,833,000 Program AFG/620070 Public Administration Reform (PAR) WB 3,169,000 Capacity Building Project for Finance and AFG/620096 WB 156,000 Administration AFG/620105 Capacity Building Program for Civil Servants GoA 3,000 Independent Directorate of Local 23,523,000 Governance Reconstruction of Nangarhar Provincial AFG/590003 GoA 21,000 Headquarters AFG/590008 SDP in border province (Local Governance) India 102,000 AFG/590038 Supplying of services in districts levels. -

Afghanistan Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey 2010-2011

Afghanistan Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey 2010-2011 Central Statistics Organisation (CSO) UNICEF (United Nations Children s Fund) January 2013 The Afghanistan Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (AMICS) was carried out in 2010-2011 by the Central Statistics Organisation (CSO) of the Government of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan in collaboration with United Nations Children s Fund (UNICEF). Financial and technical support was provided by UNICEF. MICS is an international household survey programme developed by UNICEF. The Afghanistan MICS was conducted as part of the fourth global round of MICS surveys (MICS4). MICS provides up-to-date information on the situation of children and women, and measures key indicators to monitor progress towards the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), the Afghanistan National Development Strategy (ANDS) and other internationally agreed upon commitments. Suggested citation: Central Statistics Organisation (CSO) and UNICEF (2012). Afghanistan Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey 2010-2011: Final Report. Kabul: Central Statistics Organisation (CSO) and UNICEF. Photos Copyright: Chapter 1: © UNICEF/NYHQ2007-1196/Noorani Report Cover Photos: Chapter 2: © UNICEF/NYHQ2000-0859/LeMoyne © UNICEF/AFGA2007-00819/Noorani Chapter 3: © UNICEF/AFGA2011-00116/Aziz Froutan © UNICEF/AFGA2009-00802/Shehzad Noorani Chapter 4: © UNICEF/AFGA2009-00654/Noorani © UNICEF/AFGA2010-01134/Noorani Chapter 5: © UNICEF/NYHQ2001-0491/Noorani Chapter 6: © UNICEF/AFGA2011-00010/Jalali Chapter 7: © UNICEF/AFGA2009-00546/Noorani Chapter 8: © UNICEF/NYHQ1992-0344/Isaac Chapter 9: © UNICEF/NYHQ2001-0486/Noorani Chapter 10: © UNICEF/NYHQ2007-1106/Noorani Chapter 11: © UNICEF/AFGA2010-00211/Noorani Chapter 12: © UNICEF/AFGA2007-00043/Khemka Report Copyright © Central Statistics Organization, 2012 ii Foreword After over three decades of armed conflict, Afghanistan has made great strides in overcoming some of the legacies of the past, amidst ongoing challenges and hope for the future. -

Between Hope and Fear: Rural Afghan Women Talk About Peace and War

Martine van Bijlert Between Hope and Fear: Rural Afghan women talk about peace and war Afghanistan Analysts Network, Special Report, July 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY . 3 AIMS AND STRUCTURE OF THE REPORT . 8 CHAPTER 1 METHODOLOGY . 12 CHAPTER 2 SECURITY IN THE DISTRICTS: FREEDOM FROM CONFLICT AND FEAR, FREEDOM OF MOVEMENT, ACCESS TO HEALTH AND EDUCATION . 16 2.1 Security in the districts: Do you consider your district to be safe? . 17 2.2 Freedom of movement: How often do you go outside your home? . 25 2.3 Impact of the war: Have you suffered any losses due to the war? . 32 CHAPTER 3 VIEWS ON THE US-TALEBAN AGREEMENT AND HOW IT MIGHT AFFECT THEIR LIFE . 36 3.1 The US-Taleban agreement: Have you heard of it? What are your feelings about it? . 37 3.2 Possible impact of a peace deal with the Taleban: How would it affect you personally? How would it affect what you could do? . 46 CHAPTER 4 IMAGINING WHAT PEACE COULD LOOK LIKE . 49 CHAPTER 5 LOOKING BACK AND LOOKING AHEAD: WHAT HAS BEEN GAINED, WHAT HAS BEEN LOST AND WHAT CAN ONLY BE HOPED FOR? . 59 5.1 Brief update, since we last spoke to the interviewees . 60 5.2 What these findings tell us . 63 ANNEXES . 68 ANNEX 1. INTERVIEW QUESTIONS FOR THE RURAL WOMEN AND PEACE STUDY . 69 ANNEX 2. OPEN LETTER TO WOMEN WORLD LEADERS BY “OUR VOICES OUR FUTURE” . 71 ANNEX 3. OPEN LETTER ADDRESSED TO THE TALEBAN BY “OUR VOICES OUR FUTURE” . 73 AUTHOR . 75 Rural Afghan women talk about peace and war 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY As the United States proceeds with the rapid and unconditional withdrawal of its troops from Afghanistan, an unrelenting Taleban offensive is pushing the Afghan government out of scores of districts across the country. -

Funding Agency

iRKMENIST rk ti moonri....,sr; Ammon,) FAW(A13 SAR EPOWAm"etArl His - alma sh_ve Now Oil9hdwin HERAT .-- ) t-- 7-----i ..L.....e. oRuzwAN 1..r- GHAz ii (..- i. I Twin .i.,/--..1. siaslihran .1/ \i. PAKTIKA / ...i r Oit/L A.t / zABaL * .J -%,. Lishk..G. t-,, \ is*,i 1HELMAND/ KANDA NiMRÚV I 1.40/ . Afghanistar I e fI* Funding Agency National Endowment for Democracy Supporting Ire-rd.:In around thr VW, la ANCB MEMBER NGOs Dir yof A4eber 2007 [email protected] www.ancb.org Preface We are pleased to present the updated data directory of ANCB for 2007. This editioncontains ,,.nvdated information and details of ANCB member organizations whichare strive for the provision of humanitarian services to the people of Afghanistan. The information has been collected by the ANCB staff, provided by member NGOsand efforts have been made to make sure the accuracy of the information, however. this doesnot include all Afghan NGOs which are registered with the Government of Islamic Republic ofAfghanistan and confined to only ANCB members. Weare also working on improving our communication network with our members especially with those inmore remote provinces. This will make sure collection of more information faster and reliable. We would also like to thank all NGOs who have contributedto this directory and hope for their continued support in keeping future issues complete and accurate and wouldrequest to all those members who were not able to provide information for this issueto provide their organizations information necessary for the next issue of this directory. I hope this directory will serve the Donor & UN agencies, Government of Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, International Community and other stakeholders with useful information about ANCB member NGOs and will enable them to have a clear and comprehensive picture of the activities of Afghan NGOs. -

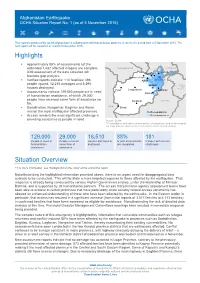

Highlights Situation Overview

Afghanistan Earthquake OCHA Situation Report No. 1 (as of 5 November 2015) This report is produced by OCHA Afghanistan in collaboration with humanitarian partners. It covers the period from 4-5 November 2015. The next report will be issued on or around 8 November 2015. Highlights • Approximately 88% of assessments (of the estimated 1,482 affected villages) are complete. TURKMENISTAN TAJIKISTAN IOM assessment of the data collected will Fayzabad Kunduz facilitate gap analysis. Mazar-e-Sharif • Verified reports indicate: 110 fatalities; 498 Aybak Epicentre people injured; 12,215 damaged and 6,295 Kabul Jamm u and houses destroyed. Ka shmir • Herat Chaghcharan Jalalabad Assessments indicate 129,000 people are in need Gardez of humanitarian assistance, of which 29,000 people have received some form of assistance so Kandahar PAKISTAN far. IRAN • Badakhshan, Nangarhar, Baghlan and Kunar Zaranj remain the most earthquake affected provinces. Affected districts • Access remains the most significant challenge in Affected provinces providing assistance to people in need. Source: OCHA The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. 129,000 29,000 18,510 88% 181 People in need of People received Houses damaged or of joint assessments Villages with access humanitarian some form of destroyed are completed. challenges assistance assistance Situation Overview + For more information, see “background on the crisis” at the end of the report. Notwithstanding the highlighted information provided above, there is an urgent need for disaggregated data analysis to be conducted. This will facilitate a more targeted response to those affected by the earthquake. -

Annual Narrative Report 2010

Afghan Civil Society Forum-organization (ACSFo) Annual Narrative Report 2010 Compiled by the Public Relation Section Afghanistan Civil Society Forum-organization House No. 48, Shahr Ara Wat, Shahr-e Naw Opposite Malalai Maternity Hospital Kabul, Afghanistan 0093-700-277-284 www.acsf.af Contents Acknowledgement 1 ADVOCACY SECTION 3 Introduction 3 Goals and Objectives: 4 Main Activities 4 Advocacy Methodology Training Manual 4 Girls Education in Afghanistan: 7 Advocating for the Rights of Persons with Disability: 8 Environment Protection Advocacy Committee: 9 Afghan Youth Advocacy Committee: 10 Conferences, Events and Meetings 11 Proposals and Concept Notes 15 Lessons Learned 18 Success Story 19 Challenges and Recommendations 20 CIVIC EDUCATION SECTION 21 Introduction 21 Goal: 22 Objectives: 22 Main Activities 22 Success Stories 26 Challenges and Recommendations 26 CAPACITY BUILDING SECTION: INITIATIVE TO PROPMOTE AFGHAN CIVIL SOCIETY (I-PACS) 28 Introduction: 28 Objectives: 28 1. To strengthen ACSFo capacity, systems and structure: 28 2. To develop capacity of partners Organizations (CSSCs): 29 3. To develop capacity of target Civil Society Organizations (CSOs): 29 The Beneficiaries of this Center: 34 Success Story: 36 Lessons Learnt: 36 Challenges /Recommendations: 36 MONITORING AND EVALUATION (M&E) SECTION 37 Introduction 37 Goals and Objectives 37 Main Activities 37 Capacity Building (Training Monitoring): 37 Training Evaluation Data (entry): 38 Civic Education (face to face session monitoring): 40 Good Governance (committees feedback -

AADO Annual Report 2011

AADO ANNUAL REPORT For the year ending 30 June 2011 About AADO AADO, the Afghan Australian Development Organisation is a voluntary, non-profit, non-government, member organisation. Its primary purpose is to implement projects that assist in the reconstruction and sustainable development of communities within Afghanistan. Within Australia, AADO seeks to support the Afghan community. Our vision Our organisation AADO’s vision is for stronger, chiefs and village elders, as With an elected Committee self-supporting families and their well as relevant government of Management, AADO is communities in Afghanistan. ministries. registered as an Incorporated Association in Victoria, Our approach To help alleviate poverty and achieve the Millennium Australia. AADO is a member AADO’s work in Afghanistan Development Goals, AADO’s of the Australian Council for is guided by the principle delivery of community International Development that education is one of the development initiatives in (ACFID) and is a signatory to the key cornerstones in ensuring Afghanistan, involves wide Council’s Code of Conduct. This poverty reduction and participation and close defines minimum standards sustainable development. Its collaboration with local in- of governance, management, major focus is the creation country partners. Recognition financial control and reporting and delivery of formal and of Afghan culture and traditions non-formal educational and is integral to the design and with which Australian non- training opportunities for the delivery of AADO’s programs.