Android User Interface Development Beginner's Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John Athayde and Bruce Williams — «The Rails View

What readers are saying about The Rails View This is a must-read for Rails developers looking to juice up their skills for a world of web apps that increasingly includes mobile browsers and a lot more JavaScript. ➤ Yehuda Katz Driving force behind Rails 3.0 and Co-founder, Tilde In the past several years, I’ve been privileged to work with some of the world’s leading Rails developers. If asked to name the best view-layer Rails developer I’ve met, I’d have a hard time picking between two names: Bruce Williams and John Athayde. This book is a rare opportunity to look into the minds of two of the leading experts on an area that receives far too little attention. Read, apply, and reread. ➤ Chad Fowler VP Engineering, LivingSocial Finally! An authoritative and up-to-date guide to everything view-related in Rails 3. If you’re stabbing in the dark when putting together your Rails apps’ views, The Rails View provides a big confidence boost and shows how to get things done the right way. ➤ Peter Cooper Editor, Ruby Inside and Ruby Weekly The Rails view layer has always been a morass, but this book reins it in with details of how to build views as software, not just as markup. This book represents the wisdom gained from years’ worth of building maintainable interfaces by two of the best and brightest minds in our business. I have been writing Ruby code for over a decade and Rails code since its inception, and out of all the Ruby books I’ve read, I value this one the most. -

Html Cheat Sheet

BEGINNER’S_ HTML CHEAT SHEET Main root 2 Document metadata 2 Sectioning root 3 Content sectioning 3 Text content 4 Inline text semantics 6 Image and multimedia 8 Scripting 9 Demarcating edits 9 Table content 9 Forms 11 Interactive elements 12 WebsiteSetup.org - Beginner’s HTML Cheat Sheet 1 Main root <html> … </html> The HTML <html> element represents the root (top-level element) of an HTML document, so it is also referred to as the root element. All other elements must be descendants of this element. Example: <!DOCTYPE html> <html lang="en"> <head>...</head> <body>...</body> </html> Document metadata <head> … </head> The HTML <head> element contains machine-readable information (metadata) about the document, like its title, scripts, and style sheets. <link> The HTML External Resource Link element (<link>) specifies relationships between the current document and an external resource. This element is most commonly used to link to stylesheets, but is also used to establish site icons (both "favicon" style icons and icons for the home screen and apps on mobile devices) among other things. <meta> The HTML <meta> element represents metadata that cannot be represented by other HTML meta-related elements, like <base>, <link>, <script>, <style> or <title> <style> … </style> The HTML <style> element contains style information for a document, or part of a document. <title> … </title> The HTML Title element (<title>) defines the document's title that is shown in a browser's title bar or a page's tab. Example: WebsiteSetup.org - Beginner’s HTML Cheat Sheet 2 <!DOCTYPE html> <html lang="en"> <head>...</head> <body>...</body> </html> Sectioning root <body> … </body> The HTML <body> Element represents the content of an HTML document. -

Microdata 184 Cross-Document Messaging 187 Accessible Rich Internet Applications (ARIA) 188 Accessibility 188 in Conclusion 191

Mobile HTML5 Estelle Weyl Mobile HTML5 by Estelle Weyl Copyright © 2014 Estelle Weyl. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Published by O’Reilly Media, Inc., 1005 Gravenstein Highway North, Sebastopol, CA 95472. O’Reilly books may be purchased for educational, business, or sales promotional use. Online editions are also available for most titles (http://my.safaribooksonline.com). For more information, contact our corporate/ institutional sales department: 800-998-9938 or [email protected]. Editors: Simon St. Laurent and Meghan Blanchette Indexer: Lucie Haskins Production Editor: Kristen Brown Cover Designer: Randy Comer Copyeditor: Kiel Van Horn Interior Designer: David Futato Proofreaders: Troy Mott and Jasmine Kwityn Illustrator: Rebecca Demarest November 2013: First Edition Revision History for the First Edition: 2013-11-12: First release See http://oreilly.com/catalog/errata.csp?isbn=9781449311414 for release details. Nutshell Handbook, the Nutshell Handbook logo, and the O’Reilly logo are registered trademarks of O’Reilly Media, Inc. Mobile HTML5, the image of a Racket-tailed Drongo, and related trade dress are trademarks of O’Reilly Media, Inc. Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and O’Reilly Media, Inc., was aware of a trade‐ mark claim, the designations have been printed in caps or initial caps. While every precaution has been taken in the preparation of this book, the publisher and author assume no responsibility for errors or omissions, or for damages resulting from the use of the information contained herein. ISBN: 978-1-449-31141-4 [LSI] Table of Contents Introduction. -

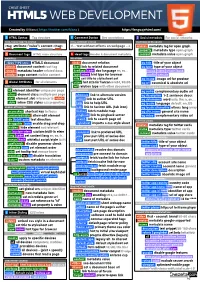

HTML5 Cheatsheet 2019

CHEAT SHEET HTML5 WEB DEVELOPMENT Created by @Manz ( https://twitter.com/Manz ) https://lenguajehtml.com/ S HTML Syntax Tag structure C Comment Syntax Dev annotations S Social metadata For social networks HTML TAG/ATTRIBUTE SYNTAX HTML COMMENT SYNTAX FACEBOOK OPEN GRAPH <tag attribute="value"> content </tag> <!-- text without effects on webpage --> <meta> metadata tag for open graph property metadata type open graph D Document tags HTML main structure H Head tags Header & document metadata content metadata value open graph MAIN TAGS RELATIONS REQUIRED METADATA PROPERTIES <!DOCTYPE html> HTML5 document <link> document relation og:title title of your object <html> document content root tag href link to related document og:type type of your object <head> metadata header related docs hreflang code doc language en, es... music video article book <body> page content visible content type mime hint type for browser profile website title set title to stylesheet set og:image image url for preview G Global Attributes for all elements sizes hint size for favicon 64x64, 96x96 og:url canonical & absolute url DOM / STYLE ATTRIBUTES rel relation type with other document OPTIONAL METADATA PROPERTIES id element identifier unique per page BASIC RELATION og:audio complementary audio url class element class multiple per page alternate link to alternate version og:description 1-2 sentence descr. slot element slot reference to <slot> author link to author URL og:determiner word auto, the, a, an, ... style inline CSS styles css properties help link to help URL -

Focus Styles

Searching accessible components Sami Keijonen Recourses ● Guide to accessible components in Smashing Magazine. ● WAI-ARIA practises. ● Scott O’Haras accessible components. Components like (1/2) ● Focus styles ● Navigation ● Icon only components (social links) ● “Cards” (image, heading, text linking to article) ● Modal dialogs Components like (2/2) ● Accordion ● Tabs ● Styling checkboxes and radio buttons ● “Autocomplete” (dynamic search results) A11y Figma Kit ● A11y Figma Kit for inspiration and reminder. ○ Article explaining the a11y Figma Kit. ● Accessibility plugins for Figma. Focus styles ● All interactive elements (links, form elements etc.) should have focus styles. ○ Crucial for keyboard users. ● Remember to style focus styles in design process (not just hover). In WCAG 2.1 there is only color contrast 3:1 guideline. :focus { Focus styles outline: 0.25rem solid #222; } Color contrast? In 2.2 draft there are also guidelines for change of contrast and minimum area. Focus styles Note that if box-shadow is used, still use transparent outline for WIN high contrast mode. Good examples Never use :focus { outline: 0 } CSS :focus { box-shadow: ... outline: 0.25rem solid transparent; } :focus-visible is for that and now also Safari 14.1 supports it. // Base focus styles :focus { outline: 0.25em solid $color; Focus styles outline-offset: 0.25em; } What about when focus styles // Be careful to remove focus styles are triggered also using mouse // for “mouse” users. click? :focus:not(:focus-visible) { outline: none; More about focus styles. } <nav> <ul> Navigation <li><a href=”url”>Link 1</a></li> <li><a href=”url”>Link 2</a></li> </ul> Start with semantic markup </nav> Navigation <nav aria-label=”Main”> If there are several <ul> navigation, it’s good to add <li><a href=”url”>Link 1</a></li> name using aria-label <li><a href=”url”>Link 2</a></li> attribute. -

Understanding Disability and Assistive Technology

Free ebooks ==> www.ebook777.com BOOKS FOR PROFESSIONALS BY PROFESSIONALS® O Connor RELATED Pro HTML5 Accessibility Build exciting, accessible, and usable web sites and apps with Pro HTML5 Accessibility. This book walks you through the process of designing user interfaces to be used by everyone, regardless of ability. It gives you the knowledge and skills you need to use HTML5 to serve the needs of the widest possible audience, including people with disabilities using assistive technology (AT) and older people. With Pro HTML5 Accessibility, you’ll learn: • How accessibility makes for good web site design • The fundamentals of ATs and how they interact with web content • How to apply HTML5 to your web projects in order to design more accessible content • How JavaScript and WAI-ARIA can be used with HTML5 to support the development of accessible web content • Important usability and user-centered design techniques that can make your HTML5 projects reach a wider audience Filled with practical advice, this book helps you master HTML5 and good accessibility design. It explores the new semantics of HTML5 and shows you how to combine them with authoring practices you may know from using earlier versions of HTML. It also aims to demonstrate how HTML5 content is currently supported (or not) by ATs such as screen readers and what this practically means for you as you endeavor to make your HTML5 projects accessible. Shelve in Web Design/HTML User level: Intermediate–Advanced SOURCE CODE ONLINE www.apress.com www.ebook777.com Free ebooks ==> www.ebook777.com For your convenience Apress has placed some of the front matter material after the index. -

Jedit 5.6 User's Guide the Jedit All-Volunteer Developer Team Jedit 5.6 User's Guide the Jedit All-Volunteer Developer Team

jEdit 5.6 User's Guide The jEdit all-volunteer developer team jEdit 5.6 User's Guide The jEdit all-volunteer developer team Legal Notice Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.1 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with no “Invariant Sections”, “Front-Cover Texts” or “Back-Cover Texts”, each as defined in the license. A copy of the license can be found in the file COPYING.DOC.txt included with jEdit. I. Using jEdit ............................................................................................................... 1 1. Conventions ...................................................................................................... 2 2. Starting jEdit .................................................................................................... 3 Command Line Usage .................................................................................... 3 Miscellaneous Options ........................................................................... 4 Configuration Options ............................................................................ 4 Edit Server Options ............................................................................... 4 Java Virtual Machine Options ........................................................................ 5 3. jEdit Basics ...................................................................................................... 7 Interface Overview ....................................................................................... -

Jedit 4.1 User's Guide

jEdit 4.1 User’s Guide jEdit 4.1 User’s Guide Copyright © 1999, 2003 Slava Pestov Copyright © 2001, 2002 John Gellene Legal Notice Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.1 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with no “Invariant Sections”, “Front-Cover Texts” or “Back-Cover Texts”, each as defined in the license. A copy of the license can be found in the file COPYING.DOC.txt included with jEdit. Table of Contents I. Using jEdit ........................................................................................................................ ix 1. Starting jEdit ................................................................................................................1 1.1. Conventions ......................................................................................................1 1.2. Platform-Independent Instructions....................................................................2 1.3. Starting jEdit on Windows................................................................................3 1.4. Command Line Usage.......................................................................................4 2. jEdit Basics ..................................................................................................................7 2.1. Buffers...............................................................................................................7 2.1.1. Memory Usage.......................................................................................7 -

Enriching Unstructured Media Content About Events to Enable Semi-Automated Summaries, Compilations, and Improved Search by Leveraging Social Networks

Enriching Unstructured Media Content About Events to Enable Semi-Automated Summaries, Compilations, and Improved Search by Leveraging Social Networks Thomas Steiner Departament de Llenguatges i Sistemes Informàtics Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya A thesis submitted for the degree of Philosophiæ Doctor (PhD) February 2014 1st Advisor: Joaquim Gabarró Vallés Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya, Barcelona, Spain 2nd Advisor: Michael Hausenblas Digital Enterprise Research Institute, Galway, Ireland MapR Technologies, San Jose, CA, USA ii Abstract (i) Mobile devices and social networks are omnipresent Mobile devices such as smartphones, tablets, or digital cameras together with social networks enable people to create, share, and consume enormous amounts of media items like videos or photos both on the road or at home. Such mobile devices—by pure definition—accompany their owners almost wherever they may go. In consequence, mobile devices are omnipresent at all sorts of events to capture noteworthy moments. Exemplary events can be keynote speeches at conferences, music concerts in stadiums, or even natural catastrophes like earthquakes that affect whole areas or countries. At such events—given a stable network connection—part of the event-related media items are published on social networks both as the event happens or afterwards, once a stable network connection has been established again. (ii) Finding representative media items for an event is hard Common media item search operations, for example, searching for the of- ficial video clip for a certain hit record on an online video platform can in the simplest case be achieved based on potentially shallow human-generated metadata or based on more profound content analysis techniques like optical character recognition, automatic speech recognition, or acoustic fingerprint- ing. -

Luxology Modo Scripting & Commands

Luxology modo Scripting & Commands Copyright ©2001-2012 Luxology, LLC. All Rights Reserved. Patents Pending. Scripting and Commands!modo!Luxology, LLC IMPORTANT NOTE: THIS DOCUMENT IS NOW OBSOLETE As of modo 601, the Scripting and Commands document should be considered obsolete, and may be incomplete. It is now superseded by the Luxology SDK Wiki. The wiki contains all of the information present here, and provides more up-to-date information, user-edited and submitted articles, and the latest corrections, and includes both scripting language and C++ SDK documentation, as well as information about kits, config files and other developer-related materials. We expect the wiki to be a much improved source of information over this document. Be sure to visit sdk.luxology.com for the up-to-date wiki. Happy Coding! -- The Luxology Team Version 4.2!Page 1 of 299 Scripting and Commands!modo!Luxology, LLC Scripting and Commands!...............................................................17 Command System!...........................................................................18 Command History Viewport!...........................................................................................18 Command Entry!.............................................................................................................................18 Undo List!.........................................................................................................................................19 History!............................................................................................................................................20 -

Realbasic 2006 User's Guide

WWWREALBASICCOM 5SERS'UIDE REALbasic 2006 User’s Guide Documentation by David Brandt. © 1999-2006 by REAL Software, Inc. All rights reserved. WASTE Text Engine © 1993-2005 Marco Piovanelli Printed in U.S.A. Mailing Address REAL Software, Inc. 1705 South Capital of Texas Highway Suite 310 Austin, TX 78746 Web Site http://www.realsoftware.com ftp Site ftp://ftp.realsoftware.com Support REALbasic Feedback at the REAL Software web site. Bugs/ Submit via REALbasic Feedback at the REAL Software Feature Requests web site. Database Plug- The REALbasic CD; the most recent versions are at ins www.realsoftware.com. Sales [email protected] Phone 512-328-REAL (7325) Fax 512-328-7372 Version 2006R1, January, 2006 Contents CHAPTER 1 Introduction . 17 Contents . 17 Welcome to REALbasic . 18 Installing REALbasic . 19 Windows Requirements. 19 Linux Requirements . 19 Macintosh Requirements . 19 Where to Begin . 19 Documentation Conventions . 20 Using the On-Line Help . 21 Searching the Online Reference . 21 Context-Sensitive Help . 22 Context-Sensitive Error Messages . 23 Using Tips . 23 Electronic Documentation . 24 Our Support Web Page . 25 End User Web Sites . 25 REALbasic Developer . 25 REALbasic third-party Books . 25 The REALbasic CD . 25 Our Internet Mailing Lists. 25 Technical Support from REAL Software . 25 Contacting REAL Software . 26 Reporting Bugs and Making Feature Requests . 26 CHAPTER 2 Getting Started with REALbasic . 27 Contents . 27 Concepts . 28 Applications are Driven by Events . 28 REALbasic User’s Guide 3 Contents Developing Software with REALbasic . 28 The Development Environment . 29 The REALbasic IDE Window. 29 The Project Editor . 31 The Window Editor . 32 The Code Editor . -

Level Access AMP Access Assistant Access University Access Analytics

Level Access AMP, Access Assistant, Access University, Access Analytics and Electronic Docs Accessibility Conformance Report Revised Section 508 Edition VPAT® Version 2.3 – December 2018 Name of Product/Version: AMP (Level Access’s Accessibility Management Platform), including Access Assistant, Access University, Access Analytics and its Electronic Docs. Product Description: AMP is an accessibility management platform that provides the structure to facilitate and organize all aspects of successful digital accessibility initiatives. AMP’s powerful testing engine and workflow, intelligent reporting, accessible development best practices, and extensive training course library allow organizations to quickly and efficiently build, test, and maintain accessible software. Access Assistant, which comes with AMP, is a browser plug-in for Chrome, Firefox, and Internet Explorer that integrates with AMP to support dynamic testing 800.889.9659 | [email protected] PAGE 1 OF 38 directly in the browser, with the option to save results directly into AMP. Testing results can be exported to Excel and PDF documents (for the purposes of this ACR, only PDFs were tested). Date: May 28, 2019 Contact information: Notes: Testing was performed on Microsoft Windows 10 desktop PCs with the Firefox 61 browser. Evaluation Methods Used: Testing AMP with Access Assistant, Access University, Access Analytics and its Electronic Docs involved a combination of manual and functional testing. Level Access (Level) comprehensively tested a selection of pages representative of AMP, Access Assistant, Access University, Access Analytics and its Electronic Docs using, among other methodology, the screen reader JAWS 2018, exclusive use of the keyboard, and manual inspection of code and Accessibility API output (through the use of tools, such as Microsoft Inspect).