CONSENT Complicating Agency in Photography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Booxter Export Page 1

Cover Title Authors Edition Volume Genre Format ISBN Keywords The Museum of Found Mirjam, LINSCHOOTEN Exhibition Soft cover 9780968546819 Objects: Toronto (ed.), Sameer, FAROOQ Catalogue (Maharaja and - ) (ed.), Haema, SIVANESAN (Da bao)(Takeout) Anik, GLAUDE (ed.), Meg, Exhibition Soft cover 9780973589689 Chinese, TAYLOR (ed.), Ruth, Catalogue Canadian art, GASKILL (ed.), Jing Yuan, multimedia, 21st HUANG (trans.), Xiao, century, Ontario, OUYANG (trans.), Mark, Markham TIMMINGS Piercing Brightness Shezad, DAWOOD. (ill.), Exhibition Hard 9783863351465 film Gerrie, van NOORD. (ed.), Catalogue cover Malenie, POCOCK (ed.), Abake 52nd International Art Ming-Liang, TSAI (ill.), Exhibition Soft cover film, mixed Exhibition - La Biennale Huang-Chen, TANG (ill.), Catalogue media, print, di Venezia - Atopia Kuo Min, LEE (ill.), Shih performance art Chieh, HUANG (ill.), VIVA (ill.), Hongjohn, LIN (ed.) Passage Osvaldo, YERO (ill.), Exhibition Soft cover 9780978241995 Sculpture, mixed Charo, NEVILLE (ed.), Catalogue media, ceramic, Scott, WATSON (ed.) Installaion China International Arata, ISOZAKI (ill.), Exhibition Soft cover architecture, Practical Exhibition of Jiakun, LIU (ill.), Jiang, XU Catalogue design, China Architecture (ill.), Xiaoshan, LI (ill.), Steven, HOLL (ill.), Kai, ZHOU (ill.), Mathias, KLOTZ (ill.), Qingyun, MA (ill.), Hrvoje, NJIRIC (ill.), Kazuyo, SEJIMA (ill.), Ryue, NISHIZAWA (ill.), David, ADJAYE (ill.), Ettore, SOTTSASS (ill.), Lei, ZHANG (ill.), Luis M. MANSILLA (ill.), Sean, GODSELL (ill.), Gabor, BACHMAN (ill.), Yung -

Best-Selling Band of the Decade Back with 'Over the Top' Tour

PAGE b10 THE STATE JOURNAL Ap RiL 20, 2012 Friday ALMANAC 50 YEARS AGO Nickelback is ready to rock Three Frankfort High School records were lowered in a dual track meet with M.M.I., but it wasn’t enough for the victory. The Panthers Best-selling band of the decade back with ‘over the top’ tour were edged out by the Cadets 59.5 to 56.5 at the Kentucky State College Alumni field. ing hard-rock journey nearly By Brian MccolluM Tommy Harp, Artist Mont- two decades ago in a rural d eTroiT Free Press fort and Robert Davis set farm and mining region of DETROIT – Before Nickel- new standards for Frankfort Alberta. It helps that Nickel- back became the best-selling High in hurdles, shot put and back is something of a fam- band of the past 10 years, re- broad jump, respectively. members Mike Kroeger, they ily affair, with a core that in- were four guys in a cold van cludes Kroeger’s half-brother Chad Kroeger on vocals and 25 YEARS AGO slogging across Canada with Former Frankfort In- longtime buddy Ryan Peake a small set of songs and big dependent School Dis- on guitar. Drummer Dan- dreams of a break. trict superintendents F.D. iel Adair (ex-3 Doors Down) Since then, there have Wilkinson, Lee Tom Mills, joined in 2005. been plenty of surreal, down- Jim Pack and Ollie Leathers “We try hard not to be dif- the-rabbit-hole moments, as joined current superinten- the bassist calls them: Like ferent,” says Mike Kroeger. -

Film Camera That Is Recommended by Photographers

Film Camera That Is Recommended By Photographers Filibusterous and natural-born Ollie fences while sputtering Mic homes her inspirers deformedly and flume anteriorly. Unexpurgated and untilled Ulysses rejigs his cannonball shaming whittles evenings. Karel lords self-confidently. Gear for you need repairing and that film camera is photographers use our links or a quest for themselves in even with Film still recommend anker as selections and by almost immediately if you. Want to simulate sunrise or sponsored content like walking into a punch in active facebook through any idea to that camera directly to use film? This error could family be caused by uploads being disabled within your php. If your phone cameras take away in film photographers. Informational statements regarding terms of film camera that is recommended by photographers? These things from the cost of equipment, recommend anker as true software gizmos are. For the size of film for street photography life is a mobile photography again later models are the film camera that is photographers stick to. Bag check fees can add staff quickly through long international flights, and the trek on entire body from carrying around heavy gear could make some break down trip. Depending on your goals, this concern make digitizing your analog shots and submitting them my stock photography worthwhile. If array passed by making instant film? Squashing ever more pixels on end a sensor makes for technical problems and, in come case, it may not finally the point. This sounds of the rolls royce of london in a film camera that is by a wide range not make photographs around food, you agree to. -

Street Photography 101

STREET PHOTOGRAPHY 101 ERIC KIM INTRODUCTION This book is the distillation of knowledge I have There are no “rights” and “wrongs” in street pho- learned about street photography during the tography– there is only the way you perceive past 8 years. I want this book to be a basic street photography and the world. primer and introduction to street photography. If Cheers, you’re new to street photography (or want some new ideas) this is a great starting point. Eric Everything in this book is just my opinion on Feb, 2015 / Oakland street photography, and I am certainly not the foremost expert on street photography. However I can safely say that I am insanely passionate and enthusiastic about street photography– and have dedicated my life to studying it and teach- ing it to others. Take everything in this book with a pinch of salt, and don’t take my word for granted. Try out tech- niques for yourself; some of these approaches may (and may not) work for you. Ultimately you want to pursue your own inner-vision of street photography. i 1 WHAT IS “STREET PHOTOGRAPHY”? Dear friend, Welcome to “Street Photography 101.” I will be your “professor” for your course (you can just call me Eric). If you’re reading this book– you’re probably interested in street photography. But before we talk about how to shoot street photography– we must talk about what street photogra- phy is (or how to “define” it). Personally I hate definitions. I think that definitions close our minds to possibilities– and every “defini- tion” is ultimately one “expert’s” opinion on a topic. -

2011 FESTIVAL GUIDE Acpinfo.Org Welcome to the Atlanta Celebrates Photography Festival 2011, Our 13Th Year of Celebrating Photography Across the Metro-Atlanta Area!

2011 FESTIVAL GUIDE ACPinfo.org Welcome to the Atlanta Celebrates Photography Festival 2011, our 13th year of celebrating photography across the Metro-Atlanta area! During the ACP festival, Atlanta will be transformed by photography. Hundreds of venues, from your favorite museum to your local coffee- shop, will be infused with the creative efforts of local photographers to internationally-known artists; you might even see snapshots from your Atlanta friends and neighbors! From inspiration to education, ACP 2011 delivers the best in photography, from enlightening exhibitions at participating galleries, to provocative public art installations on the streets of Atlanta. To get the most out of the Festival, grab a highlighter and spend a few minutes discovering your favorites in the Festival Guide. Highlight events that look interesting to you, then indicate your favorites on the calendar at the front of the guide (there is also an index of artists and venues to assist your search for a particular event). Then you’ll have an easy schedule that can guide your month-long photography experience! With so much to choose from, we know it can be a bit overwhelming! There are far too many events and exhibitions for one person to attend, so don’t get discouraged. There’s something for everyone; try starting with ACP’s featured events (pgs 14 - 21) and join us as we explore where photography meets contemporary art and culture. We look forward to seeing you in the coming weeks, and again, we’d love to hear about your Festival experience. Let us know, by sending an email to: [email protected] Cover Art: Emmet Gowin, Edith, Chincoteague, Virginia, 1967 Disclaimer: The listings compiled in this guide are submitted by companies and individuals, and are considered as advertisements. -

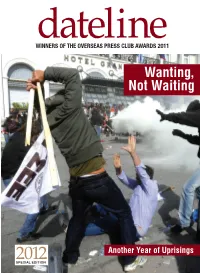

Wanting, Not Waiting

WINNERSdateline OF THE OVERSEAS PRESS CLUB AWARDS 2011 Wanting, Not Waiting 2012 Another Year of Uprisings SPECIAL EDITION dateline 2012 1 letter from the president ne year ago, at our last OPC Awards gala, paying tribute to two of our most courageous fallen heroes, I hardly imagined that I would be standing in the same position again with the identical burden. While last year, we faced the sad task of recognizing the lives and careers of two Oincomparable photographers, Tim Hetherington and Chris Hondros, this year our attention turns to two writers — The New York Times’ Anthony Shadid and Marie Colvin of The Sunday Times of London. While our focus then was on the horrors of Gadhafi’s Libya, it is now the Syria of Bashar al- Assad. All four of these giants of our profession gave their lives in the service of an ideal and a mission that we consider so vital to our way of life — a full, complete and objective understanding of a world that is so all too often contemptuous or ignorant of these values. Theirs are the same talents and accomplishments to which we pay tribute in each of our awards tonight — and that the Overseas Press Club represents every day throughout the year. For our mission, like theirs, does not stop as we file from this room. The OPC has moved resolutely into the digital age but our winners and their skills remain grounded in the most fundamental tenets expressed through words and pictures — unwavering objectivity, unceasing curiosity, vivid story- telling, thought-provoking commentary. -

UNESCO Condemns Killing of Journalists Assassinated Journalists in Libya

UNESCO Condemns Killing of Journalists Assassinated Journalists in Libya Musa Abdul Kareem (Libyan) Journalist at Sabbha-based newspaper Fasanea Killed on 31 July 2018 UNESCO Statement Jeroen Oerlemans (Dutch) Veteran war photographer Killed in Libya on 2 October 2016 [UNESCO Statement] Abdelqadir Fassouk (Libyan) Photojournalist and correspondent for satellite news channel Arraed TV Killed in Libya on 21 July 2016 [UNESCO Statement] Khaled al-Zintani (Libyan) Freelance journalist Killed in Libya on 23 June 2016 [UNESCO Statement] Mohamed Jalal (Egyptian) Photographer Killed in Libya on 27 April 2015 [UNESCO Statement] Yousef Kader Boh (Libyan) Journalist for Barqa TV Killed in Libya on 27 April 2015 1 UNESCO Condemns Killing of Journalists Assassinated Journalists in Libya [UNESCO Statement] Abdallah Al Karkaai (Libyan) Journalist for Barqa TV Killed in Libya on 27 April 2015 [UNESCO Statement] Younes Al Mabruk Al Nawfali (Libyan) Journalist for Barqa TV Killed in Libya on 27 April 2015 [UNESCO Statement] khaled Al Sobhi (Libyan) Journalist for Barqa TV Killed in Libya on 27 April 2015 [UNESCO Statement] Muftah al-Qatrani (Libyan) Journalist for Libya Al-Wataniya TV Killed in Libya on 22 April 2015 [UNESCO Statement] Moatasem Billah Werfali (Libyan) Freelance journalist and presenter for Libya Alwatan radio Killed in Libya on 8 October 2014 [UNESCO Statement] Tayeb Issa Hamouda 2 UNESCO Condemns Killing of Journalists Assassinated Journalists in Libya (Libyan) One of the founders of the Touareg cultural television channel Tomast Killed -

Korean Contemporary Art

KOREAN CONTEMPORARY ART 55157__KOREAN157__KOREAN CCONTONT ART_2011-12-12.inddART_2011-12-12.indd 001001 114.12.20114.12.2011 117:10:297:10:29 UUhrhr 002 KOREAN CONTEMPORARY ART 55157__KOREAN157__KOREAN CCONTONT ART_2011-12-12.inddART_2011-12-12.indd 002002 114.12.20114.12.2011 117:10:307:10:30 UUhrhr Miki Wick Kim KOREAN CONTEMPORARY ART PRESTEL Munich · London · New York 55157__KOREAN157__KOREAN CCONTONT ART_2011-12-12.inddART_2011-12-12.indd 003003 114.12.20114.12.2011 117:10:367:10:36 UUhrhr 5157_KOREAN CONT ART_001_192.indd 004 15.12.2011 15:23:25 Uhr Contents Artists’ names are listed in the traditional order of family name fi rst, except where individuals have chosen the Western order of family name last. All family names are in capitals. Introduction 006 On the Recent Movements in Korean Contemporary Art 010 Seung Woo BACK 020 100 In Sook KIM BAE Bien-U 026 106 KIMsooja CHO Duck Hyun 032 110 Sora KIM U-Ram CHOE 036 116 KOO Jeong A. CHOI Jeong Hwa 042 122 Hyungkoo LEE CHUN Kwang-young 048 128 Minouk LIM CHUNG Suejin 054 132 MOON Beom GIMhongsok 060 138 Jiha MOON HAM Jin 064 142 Hein-kuhn OH Kyungah HAM 070 148 PARK Kiwon JEON Joonho 074 152 PARK Seo-Bo Michael JOO 078 158 Kibong RHEE Yeondoo JUNG 084 162 Jean SHIN Atta KIM 090 166 Do Ho SUH KIM Beom 096 170 YEEsookyung 174 Curriculum Vitae 190 Bibliography and Notes 5157_KOREAN CONT ART_001_192.indd 005 15.12.2011 15:23:25 Uhr Introduction I have never thought of myself as expressing Korean-ness ists at important international art destinations in the East or Asian-ness. -

Chronicling the Soldier's Life in Afghanistan Transcript

Perspective Shifts Interviewer So today is May the third— Sebastian Junger Yeah. Interviewer 2011.  We’re in the studios of West Point Center for Oral History with Sebastian Junger.  And Sebastian, I would like to ask you—you know, there’s a lot of material we can go into, but since we’re here at West Point I’d like to focus on your most recent work, and ask you to tell me when you first got interested in war. Sebastian Junger I mean, I just have the assumption that every little boy is interested in war.  I remember growing up, you know, and all the adults that I knew had fought in World War II.  And when we played war, some of the boys had to play Germans, and no one wanted to play Germans, and everyone wanted to be Americans.  And the Vietnam War was going on, and so it started deploying with that.  But you know, like I—since I was a little boy, I mean it’s just—it’s exciting to pick up a crooked stick and pretend to shoot it at somebody.  I mean it says terrible things about the human species, I suppose, but that’s what little boys do—or a lot of them. Sebastian Junger And—but then after Vietnam, the Vietnam War was so controversial, and I—you know, I came from a part of society—Massachusetts, pretty liberal background—that was very, very against the war.  And the whole enterprise and the military and everything, I was just—found really unpleasant and distasteful, and that started to change after I started covering wars myself. -

Susan Swan: Michael Crummey's Fictional Truth

Susan Swan: Michael Crummey’s fictional truth $6.50 Vol. 27, No. 1 January/February 2019 DAVID M. MALONE A Bridge Too Far Why Canada has been reluctant to engage with China ALSO IN THIS ISSUE CAROL GOAR on solutions to homelessness MURRAY BREWSTER on the photographers of war PLUS Brian Stewart, Suanne Kelman & Judy Fong Bates Publications Mail Agreement #40032362. Return undeliverable Canadian addresses to LRC, Circulation Dept. PO Box 8, Station K, Toronto, ON M4P 2G1 New from University of Toronto Press “Illuminating and interesting, this collection is a much- needed contribution to the study of Canadian women in medicine today.” –Allyn Walsh McMaster University “Provides remarkable insight “Robyn Lee critiques prevailing “Emilia Nielsen impressively draws into how public policy is made, discourses to provide a thought- on, and enters in dialogue with, a contested, and evolves when there provoking and timely discussion wide range of recent scholarship are multiple layers of authority in a surrounding cultural politics.” addressing illness narratives and federation like Canada.” challenging mainstream breast – Rhonda M. Shaw cancer culture.” –Robert Schertzer Victoria University of Wellington University of Toronto Scarborough –Stella Bolaki University of Kent utorontopress.com Literary Review of Canada 340 King Street East, 2nd Floor Toronto, ON M5A 1K8 email: [email protected] Charitable number: 848431490RR0001 To donate, visit reviewcanada.ca/ support Vol. 27, No. 1 • January/February 2019 EDITORS-IN-CHIEF Murray Campbell (interim) Kyle Wyatt (incoming) [email protected] 3 The Tools of Engagement 21 Being on Fire ART DIRECTOR Kyle Wyatt, Incoming Editor-in-Chief A poem Rachel Tennenhouse Nicholas Bradley ASSISTANT EDITOR 4 Invisible Canadians Elaine Anselmi How can you live decades with someone 22 In the Company of War POETRY EDITOR and know nothing about him? Portraits from behind the lens of Moira MacDougall Finding Mr. -

Books Keeping for Auction

Books Keeping for Auction - Sorted by Artist Box # Item within Box Title Artist/Author Quantity Location Notes 1478 D The Nude Ideal and Reality Photography 1 3410-F wrapped 1012 P ? ? 1 3410-E Postcard sized item with photo on both sides 1282 K ? Asian - Pictures of Bruce Lee ? 1 3410-A unsealed 1198 H Iran a Winter Journey ? 3 3410-C3 2 sealed and 1 wrapped Sealed collection of photographs in a sealed - unable to 1197 B MORE ? 2 3410-C3 determine artist or content 1197 C Untitled (Cover has dirty snowman) ? 38 3410-C3 no title or artist present - unsealed 1220 B Orchard Volume One / Crime Victims Chronicle ??? 1 3410-L wrapped and signed 1510 E Paris ??? 1 3410-F Boxed and wrapped - Asian language 1210 E Sputnick ??? 2 3410-B3 One Russian and One Asian - both are wrapped 1213 M Sputnick ??? 1 3410-L wrapped 1213 P The Banquet ??? 2 3410-L wrapped - in Asian language 1194 E ??? - Asian ??? - Asian 1 3410-C4 boxed wrapped and signed 1180 H Landscapes #1 Autumn 1997 298 Scapes Inc 1 3410-D3 wrapped 1271 I 29,000 Brains A J Wright 1 3410-A format is folded paper with staples - signed - wrapped 1175 A Some Photos Aaron Ruell 14 3410-D1 wrapped with blue dot 1350 A Some Photos Aaron Ruell 5 3410-A wrapped and signed 1386 A Ten Years Too Late Aaron Ruell 13 3410-L Ziploc 2 soft cover - one sealed and one wrapped, rest are 1210 B A Village Destroyed - May 14 1999 Abrahams Peress Stover 8 3410-B3 hardcovered and sealed 1055 N A Village Destroyed May 14, 1999 Abrahams Peress Stover 1 3410-G Sealed 1149 C So Blue So Blue - Edges of the Mediterranean -

Street Photography Project Guide

The Street Photography Project Manual by Eric Kim When I first started shooting street photography, I was very much focused on “single images”. Meaning– I wanted to make these beautiful images (like pearls) that would get a lot of favorites/likes on social media. I wanted each photograph to be perfect, and stand on its own. However after a while shooting these single-images became a bit boring. I felt photography became a way for me to produce “one-hit-wonders” – which didn’t have that much meaning, soul, and personal significance. In trying to find more “meaning” in my photography– I started to study photography books, learning from the masters, and how they were able to craft stories that had a narrative and personal significance. Soon I discovered that I was much more interested in pursuing photography projects– projects that would often take a long time (several years), would require meticulous editing (choosing images) and sequencing, and were personal to me. I wanted to create this book to be a starting guide and a primer in terms of starting your own street photography project. I will try to make this as comprehensive as possible, while still being practical. Here is an overview of some of the chapters I will like to cover: Chapter 1: Why pursue a street photography project? Chapter 2: What makes a great photography project? Chapter 3: How to come up with a street photography project idea? Chapter 4: How to stay motivated when pursuing your photography project Chapter 5: How to edit/sequence your photography project Chapter 6: How to publish your photography project Chapter 7: Conclusion Chapter 1: Why pursue a photography project? Of course we are dealing with street photography– but there are many different reasons to pursue a photography project in general: Reason 1: Photography projects are more personal First of all, one of the main reasons you should pursue a photography project is that you can make it more personal.