Harps 200-Year Periods

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jahrgänge 1979-1984

T I Burgen und Schlösser in Bayern, Österreich und Südtirol Redaktion Univ.-Doz. Dr. Ernst Bacher, A-1010 Wien, und Dr. lnge Höfer, A-1010 Wien, beide Bundesdenkmalamt Herausgeber: Prof. Dr. Dr. Enno Burmeister, D-8000 München Südtiroler Burgeninstitut, Ansitz Gleifheim, St.-Anna-Str. 25, Gabriele Schmid, M.A., D-8000 München 1-39057 St. Michaei!Eppan Prof. Dr. Franz H. Ried I, 1-39100 Bozen, Garibaldistr. 36/B/20 Österreichischer Burgenverein, Parkring 2, A-1010 Wien 1 Hauptschriftleitung Verein zur Erhaltung priv. Baudenkmäler und sonst. Kulturgü• Prof. Dr. Dr. Enno Burmeister ter in Bayern e. V., Lachnerstr. 35, D-8000 München 19 Luise-Kiesselbach-Piatz 34, D-8000 München 70 Gestaltung Maler und Grafiker Walter Tafelmaier, D-8012 Ottobrunn Herstellung Athesiadruck- Graphische Betriebe Weinbergweg 7, 1-39100 Bozen Eingetragen beim Landesgericht Bozen Nr. 6/80 vom 31. 3. 1980, presserechtlich für den Inhalt verantwortlich Dr. Bernhard Freiherr von Hohenbühel, 1-39057 Eppan INHALTSVERZEICHNIS BAND I, JAHRGÄNGE 1979-1984 1. Autorenverzeichnis Abel, Christian Die Renovierung von Schloß Otterbach in der Die Rettung und Revitalisierung von Schloß Steiermark 6/1981/S. 18 Nebersdorf 2/1982/S. 36 Schloß Arnfels in der Steiermark Beitl, Klaus Schloß Kittsee im Nordburgenland und sein 2/1983/S. 38 Ethnografisches Museum 2/1982/S. 19 Allmayer-Beck, Bericht über die Generalversammlung 1979 Burmeister, Enno Holzbehandlung und Holzsanierung Max-Josef des Österreichischen Burgenvereins in Graz 1-2/1979/S. 49 1-2/1979/S. 61 Das Schloß Unterthingau 6/1981/S. 30 25 Jahre Österreichischer Burgenverein 3-4/1980/S. 53 K. F. Schinkels Schloßprojekt für Athen 1/1982/S. -

Von Leopold Josef Mayböck

l Eine besiedlungsgeschichtliche Abhandlung über das Gebiet zwischen der Großen Mühl und dem Haselgraben im Hoch- Spätmittelalter bis in die Neuzeit Von Leopold Josef Mayböck Einleitung: Seit den 80ziger Jahren war der Autor mit seiner Frau Helga, dem Burgenexperten Prof. Alfred Höllhuber aus Reichenstein, Herrn Dr. Herbert Traxler aus St. Veit und Dr. Thomas und Dr. Karin Kühtreiber aus Wien einigemal auf dieser faszinierenden Burgruine Waxenberg, sowie auf den in der Nähe befindlichen Burgstall Rotenfels im Buchholz bei Stamering. Nach einem Gespräch mit Herrn Hofrat Dr. Ernst Janko aus Linz, welcher sich mit den Familiengeschichten der Böhmerwaldfamilien Preinig, Löfler & Greipl, sowie mit der Geschichte von Vorderweißenbach beschäftigt, ein Ort der bis 1848 innerhalb des Landgerichts und Herrschaftsgebietes von Waxenberg lag, wurde beim Autor das Interesse an dieser ehemaligen großen Burgherrschaft wieder geweckt. Daraufhin wurden die vorhandenen Unterlagen im Archiv Mayböck durchgesehen, zudem ältere und neuere Literatur studiert, mit dem Ergebnis, eine kleine Arbeit zu diesem Thema zu schreiben, um meine heimatkundlichen Einschätzungen darin wiederzugeben. Die Edelfreien von Wilhering/Waxenberg: Die Stammburg dieses alten Geschlechtes befand sich in unmittelbaren Nähe der heutigen Ortschaft und Kloster Wilhering, am rechten Donauufer etwas erhöht auf einem Felsenkopf im Ortsteil Ufer; die Besitzungen erstreckten sich bis auf den großen Kürnberg. Die Lagestelle dieser Burg ist kaum mehr erkennbar, geringe Mauerreste und eine stark verschliffene Erdsubstruktion sind noch vorhanden. 1 Eine Planskizze fertigte Ludwig Benesch im Jahr 1911 an. Diese hochromanische Burganlage war ca. 6o m lang und 22 m breit das ergibt eine umbaute Fläche von ca.1.320 m² Über den Ursprung dieser alten edelfreien Familie gibt es verschiedene Annahmen, manche Historiker vermuten, daß sie aus dem bayrischen Nordgau oder Franken abstammen, 2 einer Neben- linie der Edelfreien Ötlingen aus der Gegend Bamberg. -

Lasting Legacies

Tre Lag Stevne Clarion Hotel South Saint Paul, MN August 3-6, 2016 .#56+0).')#%+'5 6*'(7674'1(1742#56 Spotlights on Norwegian-Americans who have contributed to architecture, engineering, institutions, art, science or education in the Americas A gathering of descendants and friends of the Trøndelag, Gudbrandsdal and northern Hedmark regions of Norway Program Schedule Velkommen til Stevne 2016! Welcome to the Tre Lag Stevne in South Saint Paul, Minnesota. We were last in the Twin Cities area in 2009 in this same location. In a metropolitan area of this size it is not as easy to see the results of the Norwegian immigration as in smaller towns and rural communities. But the evidence is there if you look for it. This year’s speakers will tell the story of the Norwegians who contributed to the richness of American culture through literature, art, architecture, politics, medicine and science. You may recognize a few of their names, but many are unsung heroes who quietly added strands to the fabric of America and the world. We hope to astonish you with the diversity of their talents. Our tour will take us to the first Norwegian church in America, which was moved from Muskego, Wisconsin to the grounds of Luther Seminary,. We’ll stop at Mindekirken, established in 1922 with the mission of retaining Norwegian heritage. It continues that mission today. We will also visit Norway House, the newest organization to promote Norwegian connectedness. Enjoy the program, make new friends, reconnect with old friends, and continue to learn about our shared heritage. -

№ Wca № Castles Prefix Name of Castle Oe-00001 Oe-30001

№ WCA № CASTLES PREFIX NAME OF CASTLE LOCATION INFORMATION OE-00001 OE-30001 OE3 BURGRUINE AGGSTEIN SCHONBUHEL-AGGSBACH, AGGSTEIN 48° 18' 52" N 15° 25' 18" O OE-00002 OE-20002 OE2 BURGRUINE WEYER BRAMBERG AM WILDKOGEL 47° 15' 38,8" N 12° 19' 4,7" O OE-00003 OE-40003 OE4 BURG BERNSTEIN BERNSTEIN, SCHLOSSWEG 1 47° 24' 23,5" N 16° 15' 7,1" O OE-00004 OE-40004 OE4 BURG FORCHTENSTEIN FORCHTENSTEIN, MELINDA-ESTERHAZY-PLATZ 1 47° 42' 34" N 16° 19' 51" O OE-00005 OE-40005 OE4 BURG GUSSING GUSSING, BATTHYANY-STRASSE 10 47° 3' 24,5" N 16° 19' 22,5" O OE-00006 OE-40006 OE4 BURGRUINE LANDSEE MARKT SANKT MARTIN, LANDSEE 47° 33' 50" N 16° 20' 54" O OE-00007 OE-40007 OE4 BURG LOCKENHAUS LOCKENHAUS, GUNSERSTRASSE 5 47° 24' 14,5" N 16° 25' 28,5" O OE-00008 OE-40008 OE4 BURG SCHLAINING STADTSCHLAINING 47° 19' 20" N 16° 16' 49" O OE-00009 OE-80009 OE8 BURGRUINE AICHELBURG ST. STEFAN IM GAILTAL, NIESELACH 46° 36' 38,6" N 13° 30' 45,6" O OE-00010 OE-80010 OE8 KLOSTERRUINE ARNOLDSTEIN ARNOLDSTEIN, KLOSTERWEG 3 46° 32' 55" N 13° 42' 34" O OE-00011 OE-80011 OE8 BURG DIETRICHSTEIN FELDKIRCHEN, DIETRICHSTEIN 46° 43' 34" N 14° 7' 45" O OE-00012 OE-80012 OE8 BURG FALKENSTEIN OBERVELLACH-PFAFFENBERG 46° 55' 20,4" N 13° 14' 24,6" E OE-00014 OE-80014 OE8 BURGRUINE FEDERAUN VILLACH, OBERFEDERAUN 46° 34' 12,6" N 13° 48' 34,5" E OE-00015 OE-80015 OE8 BURGRUINE FELDSBERG LURNFELD, ZUR FELDSBERG 46° 50' 28" N 13° 23' 42" E OE-00016 OE-80016 OE8 BURG FINKENSTEIN FINKENSTEIN, ALTFINKENSTEIN 13 46° 37' 47,7" N 13° 54' 11,1" E OE-00017 OE-80017 OE8 BURGRUINE FLASCHBERG OBERDRAUBURG, -

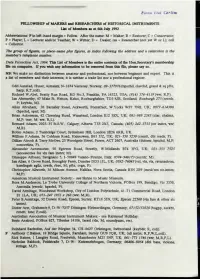

Members 1992 .Pdf

Elena Dal Cartii* FELLOWSHIP of MAKERS and RESEARCHERS of HISTORICAL INSTRUMENTS List of Members as at 6th July 1992 Abbreviations: F in left-hand margin - Fellow. After the name: M - Maker, R - Restorer, C - Conservator, P - Player, L - Lecturer and/or Teacher; W - Writer, D - Dealer, res - Researcher (not yet W or L); coll - Collector. The group of figures, or place-name plus figures, in italics following the address and a semicolon is the member's telephone number. Data Protection Act, 1984. This list of Members is the entire contents of the HonSecretary's membership file on computer. If you wish any information to be removed from this file, please say so. NB: We make no distinction between amateur and professional, nor between beginner and expert. This is a list of members and their interests; it is neither a trade list nor a professional register. Odd Aanstad, Huser, Asmaley, N-1674 Vesteroy, Norway, 09-377976{hpschd, clavchd, grand A sq pfte, harp; R.T.coll). Richard WAbel, Beatty Run Road, RD No.3, Franklin, PA 16323, USA (814) 374-4119 (ww, R,P). Ian Abemethy, 47 Main St, Heiton, Kelso, Roxburghshire, TD5 8JR, Scotland; Roxburgh 273 (recrdr, P; keybds, M). Allan Abraham, 38 Barnsley Road, Ackworth, Pontefract, W.Yorks WF7 7NB, UK; 0977-614390. (hpschd, spnt; M). Brian Ackerman, 42 Clavering Road, Wanstead, London E12 5EX, UK; 081-989 2583 (clar, chalmx, M,P; trav, M; ww, R,L). Bernard Adams, 2023-35 St.S.W., Calgary, Alberta T3E 2X5, Canada; (403) 242-3755 (str instrs, ww, M,R). Robin Adams, 2 Tunbridge Court, Sydenham Hill, London SE26 6RR, UK. -

Univerzita Palackého V Olomouci Filozofická Fakulta Katedra Dějín Umění

UNIVERZITA PALACKÉHO V OLOMOUCI FILOZOFICKÁ FAKULTA KATEDRA DĚJÍN UMĚNÍ OBOR: DĚJINY VÝTVARNÝCH UMĚNÍ ŽIVOT A DIELO SEVERONÓRSKEHO UMELCA ARNE LINDER OLSENA (1911 – 1990) MAGISTERSKÁ DIPLOMOVÁ PRÁCA Ivana Takácsová Vedúci práce: Doc. PaedDr. Alena Kavčáková, Dr. OLOMOUC 2011 PALACKY UNIVERSITY OLOMOUC PHILOSOPHICAL FACULTY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY OF ART SECTION: HISTORY OF ART LIFE AND WORK OF NORDNORWEGIAN ARTIST ARNE LINDER OLSEN (1911 – 1990) MASTER WORK Ivana Takácsová Director of master work: Doc. PaedDr. Alena Kavčáková, Dr. OLOMOUC 2011 Prehlasujem, ţe som túto magisterskú diplomovú prácu vypracovala samostatne a všetky pramene citovala a uviedla. V Olomouci dňa 23.6.2011 ................... Ďakujem Larsovi Slettjordovi a Hanne Thorp Larsen za pomoc pri celej bádateľskej činnosti a za odbornú pomoc v oblasti histórie, kultúry a umenia Nórska a mesta Narvik. Zároveň chcem poďakovať všetkým ústretovým ľuďom, ktorí mi pomáhali pri dokumentácii obrazov a získavaní informácií, predovšetkým Unni Yvonne Linder, Bjørnovi Alfovi Linder, Ørjanovi Aspelund a Harrymu Hjelle. Za odbornú pomoc a vedenie diplomovej práce ďakujem pani Doc. PaedDr. Alene Kavčákovej, Dr. OBSAH 1. Úvod................................................... 2 2. Prehľad literatúry..................................... 7 3. Úvod do nórskeho maliarskeho umenia v 20.storočí....... 10 4. Ţivotopis Arne Linder Olsena........................... 25 5. Umelecká činnosť....................................... 33 5.1. Obdobie štúdia.................................... 33 5.2. Umelecká -

Landesmuseum Joanneum Graz Jahresbericht

©Digitalisierung Biologiezentrum Linz; download www.zobodat.at LANDESMUSEUM JOANNEUM GRAZ JAHRESBERICHT 1979 ©Digitalisierung Biologiezentrum Linz; download www.zobodat.at ©Digitalisierung Biologiezentrum Linz; download www.zobodat.at LANDESMUSEUM JOANNEUM GRAZ, JAHRESBERICHT1979 ©Digitalisierung Biologiezentrum Linz; download www.zobodat.at ©Digitalisierung Biologiezentrum Linz; download www.zobodat.at LANDESMUSEUM JOANNEUM GRAZ JAHRESBERICHT 1 9 7 9 j > A m /<f i n v - bib Steierm. Landesmuseum Joanneum Abteilung für Botanik A - 801 0 Graz, Raubergasse 10 NEUE FOLGE 9 — GRAZ 1980 ©Digitalisierung Biologiezentrum Linz; download www.zobodat.at Nach den Berichten der Abteilungen redigiert von Eugen Bregant, Dr. Detlef Ernet und Dr. Friedrich Waidacher Graz 1980 Herausgegeben von der Direktion des Steiermärkischen Landesmuseums Joanneum, Raubergasse 10/I, A-8010 Graz Direktor: Dr. Friedrich WAIDACHER Gesamtherstellung: Buch- und Offsetdruckerei Styria, Judenburg Gesetzt aus Sabon — Monotype ©Digitalisierung Biologiezentrum Linz; download www.zobodat.at Inhalt Kuratorium 6 Bautätigkeit und Einrichtung 7 Sonderausstellungen 9 Veranstaltungen 15 Besuchsstatistik 1979 22 Verkäufliche Veröffentlichungen 1979. 25 Berichte Direktion 61 Referat für Jugendbetreuung. 65 Abteilung für Geologie, Paläontologie und Bergbau 69 Abteilung für Mineralogie 78 Abteilung für Botanik 88 Abteilung für Zoologie. 95 Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Vogelkunde und Biotopschutz am Landesmuseum Joanneum 107 Abteilung für Vor- und Frühgeschichte und Münzensammlung 109 Abteilung für Kunstgewerbe 117 Landeszeughaus. 127 Alte Galerie. 132 Neue Galerie 135 Steirisches Volkskundemuseum 146 Außenstelle Stainz 152 Jagdmuseum . 155 Abteilung Schloß Eggenberg 162 Landschaftsmuseum Schloß Trautenfels. 168 Bild- und Tonarchiv 172 Beitrag M. Lf.HMBRUCK, Freiraum Museumsbau 181 ©Digitalisierung Biologiezentrum Linz; download www.zobodat.at Kuratorium Das Kuratorium des Steiermärkischen Landesmuseums Joanneum hat im Berichtsjahr zwei Sitzungen abgehalten (22. Juni und 26. -

Tips Oss! 33 34 57 77 E-Post: [email protected] Nett: Facebook: Facebook.Com/Oyeneavis Kunsthistorie Kan Skape Stolthet Her

16 KULTUR Torsdag 13. august 2020 ØYENE KULTUR TIPS OSS! 33 34 57 77 E-post: [email protected] Nett: www.oyene.no Facebook: facebook.com/oyeneavis Kunsthistorie kan skape stolthet her Kunsthistoriker Mor- noen. zanne som inspirasjon, ble en ten Zondag fra Kjøp- – I 1881 kom Frits Thaulow trend å male akter i naturen, for første gang til Hvasser med ofte badende mennesker. mannskjær er Norges seilbåten. Om bord hadde han Det finnes en gruppe slike mest anerkjente en rekke andre kunstnere. De bilder fra den tiden malt av Munch-kjenner. Når malte ikke det første året, men Jean Heiberg, Per Deberitz, As- mange av dem kom senere til- tri Welhaven Heiberg med flere. han ikke reiser rundt i bake til øysamfunnet, sier Det hevdes at de ble malt på verden med Munch- kunsthistorikeren, som synes Treidene på Tjøme. Det er van- verk diskret innpak- vi kan si at Hvasser ble Norges skelig å dokumentere, fordi svar på Skagen. landskapet ikke kan gjenkjen- ket i gråpapir under – Slik danske kunstnere reiste nes. armen, er han også til Skagen, reiste norske kunst- For den som vil vite mer om spesialist på øykunst. nere til Hvasser. De reiste ikke i en enkeltkunstner som hentet flokk, slik maleriene fra Skagen inspirasjon på øyene og malte SVEN OTTO RØMCKE gir inntrykk av. Men de reiste til denne typen motiver herfra, [email protected] Hvasser av samme grunn som anbefales Øyenes intervju med 901 03 880 danskene reiste til Skagen. Ly- kunsthistoriker Signe Endre- Det betyr kunst som er blitt til set. sen. I Øyene for 12. -

Zapuščinski Inventar Po Janezu Jakobu Grofu Khislu Iz Leta 1690

Gradivo za zgodovino Maribora XLIV. zvezek ZAPUŠČINSKI INVENTAR PO JANEZU JAKOBU GROFU KHISLU IZ LETA 1690 Matjaž Grahornik Maribor 2020 POKRAJINSKI ARHIV MARIBOR Gradivo za zgodovino Maribora XLIV. zvezek ZAPUŠČINSKI INVENTAR PO JANEZU JAKOBU GROFU KHISLU IZ LETA 1690 Matjaž Grahornik Maribor 2020 1 Gradivo za zgodovino Maribora, XLIV. zvezek ZAPUŠČINSKI INVENTAR PO JANEZU JAKOBU GROFU KHISLU IZ LETA 1690 Matjaž Grahornik Izdal in založil: Pokrajinski arhiv Maribor Zanj odgovarja: Ivan Fras, prof., direktor Glavni urednik: Ivan Fras, prof. Urednica: mag. Nina Gostenčnik Prevodi povzetkov: mag. Boštjan Zajšek (nemščina), mag. Nina Gostenčnik (angleščina) Lektoriranje: mag. Boštjan Zajšek Recenzenti: dr. Žiga Oman, dr. Miha Preinfalk, dr. Vinko Skitek Oblikovanje in prelom: mag. Nina Gostenčnik CIP - Kataložni zapis o publikaciji Univerzitetna knjižnica Maribor 930.253(497.4)"1690":929Khisl J. J.(0.034.2) POKRAJINSKI arhiv Maribor Zapuščinski inventar po Janezu Jakobu grofu Khislu iz leta 1690 [Elektronski vir] / Matjaž Grahornik ; [prevodi povzetkov Boštjan Zajšek (nemščina), Nina Gostenčnik (angleščina)]. - E-knjiga. - Maribor : Pokrajinski arhiv, 2020. - (Gradivo za zgodovino Maribora ; zv. 44) Način dostopa (URL): http://www.pokarh- mb.si/uploaded/datoteke/gzm_44_2019_splet.pdf ISBN 978-961-6507-92-9 (PDF) 1. Gl. stv. nasl. 2. Grahornik, Matjaž COBISS.SI-ID 34769155 Maribor, 2020 ©Pokrajinski arhiv Maribor Izdajo tega zvezka sta omogočila Ministrstvo za kulturo Republike Slovenije in Mestna občina Maribor. 2 KAZALO VSEBINE 1. UVOD 5 2. OPOMBE K EDICIJI 7 3. SEZNAM UPORABLJENIH OKRAJŠAV 9 4. RODBINA KHISL NA SLOVENSKEM 11 4.1. Člani rodbine Khisl na Štajerskem 19 4.2. Janez Jakob (1565–1637), prvi lastnik gospostva Spodnji Maribor in prvi grof Khisl 23 4.3. -

Bibliographie Nach-Linneischer Literatur Über Die Mollusken Österreichs, II

Bibliographie nach-linneischer Literatur über die Mollusken Österreichs, II. (Stand 31. Dez. 2018) Von ALEXANDER REISCHÜTZ, PETER L. REISCHÜTZ & WOLFGANG FISCHER Horn - Wien 2019. © Erste Vorarlberger Malakologische Gesellschaft, Sulzerweg 2, A-6830 Rankweil, Österreich. Januar 2019 Autoren: Alexander Reischütz, Untere Augartenstraße 7/2/24, A-1020 Wien, Österreich. Peter L. Reischütz, Puechhaimg. 52, A-3580 Horn, Österreich. Wolfgang Fischer, Martnigasse 26, A-1220 Wien, Österreich. Bibliographie nach-linneischer Literatur über die Mollusken Österreichs, II. (Stand 31. Dez. 2018). Von ALEXANDER REISCHÜTZ, PETER L. REISCHÜTZ & WOLFGANG FISCHER, Horn - Wien. Vorwort Diese Bibliographie zeigt, dass in Österreich mit minimalen Ausnahmen nie eine naturschutzrelevante Kartierung der Molluskenfauna stattgefunden hat. Zukünftige Kartierungen werden nach den Erfahrungen der Autoren bis auf wenige Ausnahmen einen erschütternden Zustand der Biotope dieser Tiergruppe aufzeigen. „Mit dem Ausscheiden von R. STURANY (gest. 1935) aus dem aktiven Dienst beendete die offizielle Malakologie ihre Beteiligung an der Vermehrung unseres Wissens über die Weichtiere Österreichs, die bis auf weiteres fast ausschließlich von Privatpersonen getragen wurde“ (W. KLEMM in einem Gespräch mit dem Seniorautor im Dezember 1973). Während unserer Arbeiten über die Mollusken Österreichs machte sich immer wieder das Fehlen einer brauchbaren Bibliographie bemerkbar, obwohl in FRAUENFELD 1855, STURANY 1900, KLEMM 1960 und 1974, FRANK 1976 und anderen zahlreiche Literaturzitate angeführt sind. Die Überprüfung aller bis dahin zitierten Arbeiten erwies sich als notwendig, weil immer wieder Arbeiten ohne Bezug zu Österreich - oft marine Literatur und häufig auch Arbeiten über andere Tiergruppen (Insekten, Krebse, Würmer, ...) - in den Molluskenbibliographien zitiert und nicht überprüft oder falsch abgeschrieben wurden. Dadurch kam es zu langen Verzögerungen durch erhöhten zeitlichen Aufwand. -

Bykle Sokneråd

ÅRSMØTE for Bykle og Fjellgardane kyrkjelyd, i Bykle kyrkje SUNDAG 17. MARS KL.12.30 Lys Vaken 2012, f.v.: Bjørn Viki, Erik Dyrland Domaas, Terje Seilskjær. Innhald: Årsrapport 2012 for Bykle sokneråd med årsrapportar frå: Prostidiakonen i Otredal Bykle barnekor og Fjellgardane barnekor Fjellgardane sundagsskule Bykle KFUK-KFUM speidarar Pilegrimsvandring Hovden-Røldal Årsmøtet er ein stad der du kan ta opp det du er oppteken av i kyrkjelyden. Det er eit informasjons- og diskusjonsmøte, det er ikkje godkjenning av saker / val. Alle hjarteleg velkomne Bykle Sokneråd – Årsrapport 2012 Godkjent av Bykle sokneråd 6.mars 2013 1. Organisering av kyrkja .................................... 2 2. Tilsette og personalansvar ............................... 3 3. Kyrkjelydsarbeid ............................................. 4 4. Kyrkjer ............................................................ 8 5. Kyrkjegardar ................................................... 9 6. Økonomi ......................................................... 9 7. Planar for 2013 .............................................. 10 8. Takk .............................................................. 10 Fjellgardane kyrkje 1. Organisering av kyrkja Bykle sokn er eiga, juridisk eining, soknerådet er øvste organ. 21. februar 2012 var det registrert 763 medlemmar i Bykle sokn. 21.februar 2013 var medlemstalet 735. Nedgongen har truleg samanheng med reduksjon av folketalet i kommunen. Soknerådet bestod i 2012 av seks valde medlem, soknepresten og kommunen sin representant. -

Members 1995 .Pdf

O6 h 50M. 5 h rib b FELLOWSHIP of MAKERS and RESEARCHERS of HISTORICAL INSTRUMENTS List of Members as at 18 April 199S Abbreviations: F in left-hand margin - Fellow. After the name: M = Maker, R - Restorer, C - Conservator, P - Player, L - Lecturer and/or Teacher, W - Writer, D - Dealer, res - Researcher (not yet W or L); coll - Collector. The group of figures, or place-name plus figures, in italics following the address and a semicolon is the member's telephone number, fax (where stated so; '& fx' means that the same number serves both for voice telephone and fax), and electronic-mail address (indicated as e-m or em). Data Protection Act, 1984: This List of Members is the entire contents of the Hon.Secretary's membership file on computer. If you wish any information to be removed from this file, please say so. NB: We make no distinction between amateur and professional, nor between beginner and expert. This is a list of members and their interests; it is neither a trade list nor a professional register. Odd Aanstad, Huser Asmaloy, N-1684 Vesteroy, Norway; +47 6937 7976; fax 47 6937 7376 (hpschd, clavchd, grand & sq pfte, harp; R,T,coll). Richard W Abel, Beatty Run Road, RD No 3, Franklin, PA 16323, USA; (814) 374-4119 (ww, R,P). Bernard Adams, 2023-35 St SW, Calgary, Alberta T3E 2X5, Canada; (403) 242-3755 (str instrs, ww, M,R). Robin Adams, 2 Tunbridge Court, Sydenham Hill, London SE26 6RR, UK. Alexander Accessories, 50 Egerton Road, Streetly, W Midlands B74 3PG, UK; 0121-353 7525 (for vln fam; M).