Annexation and Exile in Latvia 1940-1950

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LATVIA in REVIEW July 26 – August 1, 2011 Issue 30

LATVIA IN REVIEW July 26 – August 1, 2011 Issue 30 CONTENTS Government Latvia's Civic Union and New Era Parties Vote to Participate in Foundation of Unity Party About 1,700 people Have Expressed Wish to Join Latvia's Newly-Founded ZRP Party President Bērziņš to Draft Legislation Defining Criteria for Selection of Ministers Parties Represented in Current Parliament Promise Clarity about Candidates This Week Procedure Established for President’s Convening of Saeima Meetings Economics Bank of Latvia Economist: Retail Posts a Rapid Rise in June Latvian Unemployment Down to 12.3% Fourteen Latvian Banks Report Growth of Deposits in First Half of 2011 European Commission Approves Cohesion Fund Development Project for Rīga Airport Private Investments Could Help in Developing Rīga and Jūrmala as Tourist Destinations Foreign Affairs Latvian State Secretary Participates in Informal Meeting of Ministers for European Affairs Cabinet Approves Latvia’s Initial Negotiating Position Over EU 2014-2020 Multiannual Budget President Bērziņš Presents Letters of Accreditation to New Latvian Ambassador to Spain Society Ministry of Culture Announces Idea Competition for New Creative Quarter in Rīga Unique Exhibit of Sand Sculptures Continues on AB Dambis in Rīga Rīga’s 810 Anniversary to Be Celebrated in August with Events Throughout the Latvian Capital Labadaba 2011 Festival, in the Līgatne District, Showcases the Best of Latvian Music Latvian National Opera Features Special Summer Calendar of Performances in August Articles of Interest Economist: “Same Old Saeima?” Financial Times: “Crucial Times for Investors in Latvia” L’Express: “La Lettonie lutte difficilement contre la corruption” Economist: “Two Just Men: Two Sober Men Try to Calm Latvia’s Febrile Politics” Dezeen magazine: “House in Mārupe by Open AD” Government Latvia's Civic Union, New Era Parties Vote to Participate in Foundation of Unity Party At a party congress on July 30, Latvia's Civic Union party voted to participate in the foundation of the Unity party, Civic Union reported in a statement on its website. -

Volume No. 16-02 June 2016 FRIENDS ACROSS the SEA Page

Volume No. 16-02 June 2016 ROCKVILLE SISTER CITY CORPORATION NEWSLETTER www.RockvilleSisterCities.org The Rockville Sister City Corporation (RSCC) is a non-profit corporation founded in 1986 to enhance and maintain the friendship and ‘Sister City’ relationship established by the City of Rockville in 1957 with Pinneberg, Germany, based on youth, educational, cultural and commercial exchanges pursuant to the People-To-People Program initiated by President Dwight Eisenhower in 1956 to promote world peace. PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE The RSCC Mayor and Council Meet and Greet – by Drew Powell, President, RSCC Membership Appreciation event was a resounding success with more than fifty in attendance, which Another busy and productive quarter has passed for included Rockville Mayor Bridget Newton; the Rockville Sister City Corporation. The RSCC Rockville City Councilmembers, Beryl Feinberg, team, consisting of dedicated Board members, our Virginia Onley and Mark Pierzchala; General Membership, City of Rockville Elected Montgomery County Councilmember, Marc Officials and Staff as well as Friends of RSCC, is Elrich; Rockville Police Chief, Terry Treschuk; what makes our organization so successful. Here’s Rockville Acting City Manager, Craig Simoneau; some of what we achieved in the past three months: Rockville’s New City Clerk, Kathleen Conway; Rockville Assistant City Clerk, Sara Taylor- Rockville City Councilmember, Beryl Feinberg, Ferrell; former Rockville City Mayor, Steven assumed her role as RSCC’s new City Council VanGrack; former Rockville City Councilmember Liaison. Having majored in International Studies at Bob Wright; Rockville Volunteer Fire Department American University, in addition to extensive President Eric Bernard; Rockville Planning Board international travel experience, Beryl brings a member Don Hadley; all of the Rockville Sister wealth of talent and energy well suited for her City Board of Directors; Rockville Sister City position as City Council Liaison. -

ECFG-Latvia-2021R.Pdf

About this Guide This guide is designed to prepare you to deploy to culturally complex environments and achieve mission objectives. The fundamental information contained within will help you understand the cultural dimension of your assigned location and gain skills necessary for success (Photo: A Latvian musician plays a popular folk instrument - the dūdas (bagpipe), photo courtesy of Culture Grams, ProQuest). The guide consists of 2 parts: ECFG Part 1 “Culture General” provides the foundational knowledge you need to operate effectively in any global environment with a focus on the Baltic States. Part 2 “Culture Specific” describes unique cultural features of Latvia Latvian society. It applies culture-general concepts to help increase your knowledge of your deployment location. This section is designed to complement other pre-deployment training (Photo: A US jumpmaster inspects a Latvian paratrooper during International Jump Week hosted by Special Operations Command Europe). For further information, visit the Air Force Culture and Language Center (AFCLC) website at www.airuniversity.af.edu/AFCLC/ or contact the AFCLC Region Team at [email protected]. Disclaimer: All text is the property of the AFCLC and may not be modified by a change in title, content, or labeling. It may be reproduced in its current format with the express permission of the AFCLC. All photography is provided as a courtesy of the US government, Wikimedia, and other sources. GENERAL CULTURE PART 1 – CULTURE GENERAL What is Culture? Fundamental to all aspects of human existence, culture shapes the way humans view life and functions as a tool we use to adapt to our social and physical environments. -

The Baltic Republics

FINNISH DEFENCE STUDIES THE BALTIC REPUBLICS A Strategic Survey Erkki Nordberg National Defence College Helsinki 1994 Finnish Defence Studies is published under the auspices of the National Defence College, and the contributions reflect the fields of research and teaching of the College. Finnish Defence Studies will occasionally feature documentation on Finnish Security Policy. Views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily imply endorsement by the National Defence College. Editor: Kalevi Ruhala Editorial Assistant: Matti Hongisto Editorial Board: Chairman Prof. Mikko Viitasalo, National Defence College Dr. Pauli Järvenpää, Ministry of Defence Col. Antti Numminen, General Headquarters Dr., Lt.Col. (ret.) Pekka Visuri, Finnish Institute of International Affairs Dr. Matti Vuorio, Scientific Committee for National Defence Published by NATIONAL DEFENCE COLLEGE P.O. Box 266 FIN - 00171 Helsinki FINLAND FINNISH DEFENCE STUDIES 6 THE BALTIC REPUBLICS A Strategic Survey Erkki Nordberg National Defence College Helsinki 1992 ISBN 951-25-0709-9 ISSN 0788-5571 © Copyright 1994: National Defence College All rights reserved Painatuskeskus Oy Pasilan pikapaino Helsinki 1994 Preface Until the end of the First World War, the Baltic region was understood as a geographical area comprising the coastal strip of the Baltic Sea from the Gulf of Danzig to the Gulf of Finland. In the years between the two World Wars the concept became more political in nature: after Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania obtained their independence in 1918 the region gradually became understood as the geographical entity made up of these three republics. Although the Baltic region is geographically fairly homogeneous, each of the newly restored republics possesses unique geographical and strategic features. -

Health Systems in Transition

61575 Latvia HiT_2_WEB.pdf 1 03/03/2020 09:55 Vol. 21 No. 4 2019 Vol. Health Systems in Transition Vol. 21 No. 4 2019 Health Systems in Transition: in Transition: Health Systems C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Latvia Latvia Health system review Daiga Behmane Alina Dudele Anita Villerusa Janis Misins The Observatory is a partnership, hosted by WHO/Europe, which includes other international organizations (the European Commission, the World Bank); national and regional governments (Austria, Belgium, Finland, Kristine Klavina Ireland, Norway, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the Veneto Region of Italy); other health system organizations (the French National Union of Health Insurance Funds (UNCAM), the Dzintars Mozgis Health Foundation); and academia (the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) and the Giada Scarpetti London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM)). The Observatory has a secretariat in Brussels and it has hubs in London at LSE and LSHTM) and at the Berlin University of Technology. HiTs are in-depth profiles of health systems and policies, produced using a standardized approach that allows comparison across countries. They provide facts, figures and analysis and highlight reform initiatives in progress. Print ISSN 1817-6119 Web ISSN 1817-6127 61575 Latvia HiT_2_WEB.pdf 2 03/03/2020 09:55 Giada Scarpetti (Editor), and Ewout van Ginneken (Series editor) were responsible for this HiT Editorial Board Series editors Reinhard Busse, Berlin University of Technology, Germany Josep Figueras, European -

Water Tourism D

5 POTTERY WORKSHOP OF VALDIS PAULINS CATERING SERVICES Hello, traveller! Address: Dumu Street 8, Kraslava, Kraslava municipality, Latvia 13 JAUNDOME ENVORONMENTAL EDUCATION CENTRE AND EXHIBITION HALL 21 MUSIC WORKSHOP “BALTHARMONIA” Mob.: +371 29128695 DINING HALL „ DAUGAVA” Address: Novomisli, Ezernieki rural territory, Dagda municipality, Latvia Address: "Bikava 2a", Gaigalava, Gaigalava rural territory, Rezekne municipality, Latvia CAFE “PIE ČERVONKAS PILS” This is a guide-book that will help you to experience an exciting trip along The Green Routes E-mail: [email protected] Address: Rigas Street 28, Kraslava, Mob.: +371 25960309 Phone: +371 28728790, + 371 26593441 Address: Cervonka-1, Vecsaliena rural territory, of the border areas of Latvia, Lithuania and Belarus. Routes leading to specially protected nature Website: http://www.visitkraslava.com/ Kraslavas municipality, Latvia E - mail: [email protected] E - mail: [email protected] Daugavpils municipality, Latvia areas under the state care are called “green” ones. These routes are “green” because providers of GPS: X:697648, Y:199786 / 55° 54' 10.30", 27° 9'42.27" Phone: +371 65622634, Mob.: +371 29112899 Website: www.visitdagda.com Website: http://www.baltharmonia.lv Mob.: +371 29726105 tourism service take care of accessibility of environment for people with disabilities. The workshop is around on the territory of the protected landscape Fax: +371 65622266 GPS: X:723253, Y:227872 / 56° 8' 36.72", 27° 35'88" GPS: X:687623, Y:291964 / 56° 44' 1.98", 27° 4'2.23" GPS: X: 673571, Y: 189832 / 55° 49’ 22.13’’, 26° 46’ 14.74’’ You are welcome at the places, where you will get acquainted with the values of the nature area „Augšdaugava”. -

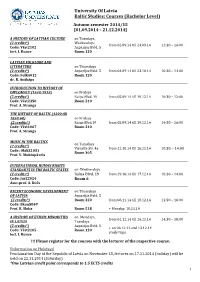

University of Latvia Baltic Studies: Courses (Bachelor Level)

University Of Latvia Baltic Studies: Courses (Bachelor Level) Autumn semester 2014/15 [01.09.2014 – 21.12.2014] A HISTORY OF LATVIAN CULTURE on Tuesdays, (2 credits*) Wednesdays from 02.09.14 till 24.09.14 12:30 – 16:00 Code: Vēst2102 Azpazijas Bvld. 5 lect. I. Runce Room 120 LATVIAN FOLKLORE AND LITERATURE on Thursdays (2 credits*) Azpazijas Bvld. 5 from 04.09.14 till 23.10.14 10:30 – 14:00 Code: Folk4012 Room 120 dr. R. Auškāps INTRODUCTION TO HISTORY OF DIPLOMACY (1648-1918) on Fridays (2 credits*) Raiņa Blvd. 19 from 05.09.14 till 19.12.14 10:30 – 12:00 Code: Vēst2350 Room 210 Prof. A. Stranga THE HISTORY OF BALTIC (1200 till 1850-60) on Fridays (2 credits*) Raiņa Blvd.19 from 05.09.14 till 19.12.14 14:30 – 16:00 Code: Vēst1067 Room 210 Prof. A. Stranga MUSIC IN THE BALTICS on Tuesdays (2 credits*) Visvalža Str. 4a from 21.10.14 till 16.12.14 10:30. – 14:00 Code : MākZ1031 Room 305 Prof. V. Muktupāvels INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS STANDARTS IN THE BALTIC STATES on Wednesdays (2 credits*) Raiņa Blvd. 19 from 29.10.14 till 17.12.14 10:30 – 14:00 Code: JurZ2024 Room 6 Asoc.prof. A. Kučs RECENT ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT on Thursdays OF LATVIA Azpazijas Bvld. 5 (2 credits*) Room 320 from 06.11.14 till 18.12.14 12:30 – 16:00 Code: Ekon5069 Prof. B. Sloka Room 518 + Monday, 10.11.14 A HISTORY OF ETHNIC MINORITIES on Mondays, from 01.12.14 till 16.12.14 14:30 – 18:00 IN LATVIA Tuesdays (2 credits*) Azpazijas Bvld. -

Read More on Baltic International

INNOVATIONS TEAM aimed at innovations EXCELLENT OF EXPERTS and excellence SERVICE 25 REASONS WE ARE PROUD OF know-how truly individual high and experience quality service FAMILY BANK a bank owned SUPPORT by family TRUST TO STARTUPS and devoted we appreciate we believe in future to families trust of clients of start-ups and employees ESG JOY OF 25YEAR Environmental. WORKING EXPERIENCE GOOD Social. TOGETHER Let’s celebrate RESOURCE BASE Government. we love to work 25th anniversary strong resource base together! on May 3 and OUR WAY and sound development entire year 2018! OF SUCCESS, CHALLENGES RELIABILITY SUSTAINABILITY we are reliable, AND gold level open and honest in Sustainability index long-term business VICTORIES partner PATRONS SUPPORT OF CULTURE TO LITERATURE WINNERS SUCCESSION AND ART we believe in power #WinnersBorninLatvia we believe in importance care for succession of literature of families and succession of national values SMART EXPERTISE INVESTMENTS helps to find OFFICE we invest with our clients the best solutions IN THE HEART in a smart way OF OLD RIGA for our customers working in the rhythm of the heartbeats of Riga RESPECTFUL SHAREHOLDERS we trust our shareholders, RESPONSIBILITY STRONG TEAM GREEN SPORTIVE AND COMPETITIVE and they trust us responsible for wealth good team of energetic THINKING ENTHUSIASTIC PRODUCTS management of our clients and loyal experts care for nature we enjoy working wide spectrum and ourselves and sporting together and competitive features Business review 2017 CONTENTS 3 Valeri Belokon, Chairman of Supervisory Board 5 Viktor Bolbat, Deputy Chairman of Management Board 7 Bank financial results review 10 Overall review of Latvian economy 13 Developments on global financial markets 15 Baltic International Bank: support to the society, environment, and the world 19 Baltic International Bank — 25! VALERI BELOKON e Chairperson of the Supervisory Board of Baltic International Bank Whatever you do in life, do it with all your heart. -

From Tribe to Nation a Brief History of Latvia

From Tribe to Nation A Brief History of Latvia 1 Cover photo: Popular People of Latvia are very proud of their history. It demonstration on is a history of the birth and development of the Dome Square, 1989 idea of an independent nation, and a consequent struggle to attain it, maintain it, and renew it. Above: A Zeppelin above Rīga in 1930 Albeit important, Latvian history is not entirely unique. The changes which swept through the ter- Below: Participants ritory of Latvia over the last two dozen centuries of the XXV Nationwide were tied to the ever changing map of Europe, Song and Dance and the shifting balance of power. From the Viking Celebration in 2013 conquests and German Crusades, to the recent World Wars, the territory of Latvia, strategically lo- cated on the Baltic Sea between the Scandinavian region and Russia, was very much part of these events, and shared their impact especially closely with its Baltic neighbours. What is unique and also attests to the importance of history in Latvia today, is how the growth and development of a nation, initially as a mere idea, permeated all these events through the centuries up to Latvian independence in 1918. In this brief history of Latvia you can read how Latvia grew from tribe to nation, how its history intertwined with changes throughout Europe, and how through them, or perhaps despite them, Lat- via came to be a country with such a proud and distinct national identity 2 1 3 Incredible Historical Landmarks Left: People of The Baltic Way – this was one of the most crea- Latvia united in the tive non-violent protest activities in history. -

The Courlander Experience in Tobago

THE COURLANDER EXPERIENCE IN TOBAGO THE REPUBLIC OF LATVIA: A maritime nation on the Baltic sea with excellent ports, 64.589km2 in area and a population of nearly 2.000.000 inhabitants. There are apx. 1.500.000 Latvians living in Latvia and the rest of the world. 2018 marks the 100th anniversary of the founding of the Republic of Latvia. COURLANDERS: Latvians from the province of Courland (Kurzeme). In the days of the Duchy of Courland and Semgallia, a “Courlander” could also be an inhabitant of the province of Semgallia. “Courlander” is a literal translation of the Latvian kurzemnieks. The academic word for anything pertaining to Courland is Couronian. THE DUCHY OF COURLAND AND SEMGALLIA: A de facto independent nation formed in 1561 and existing until 1795, comprised of 2 modern day provinces of Latvia, and ruled by the German-Baltic dukes of Courland, although officially a part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. The flags of Courland consisted of a red and white 2 band flag and the red and black “crab” flag which originated in Tobago, as there are no crabs of this type in Latvia. As such, it can be considered the first flag of Tobago. CHRONOLOGY 1639 Sent by Duke Jacob, probably involuntarily, 212 Courlanders arrive in Tobago. Unprepared for tropical conditions, they eventually perish. 1642 (possibly 1640) Duke Jacob engages a Brazilian, capt. Cornelis Caroon (later, Caron) to lead a colony comprised basically of Dutch Zealanders, that probably establishes itself in the flat, southwestern portion of the island. Under attack by the Caribs, 70 remaining members of the original 310 colonists are evacuated to Pomeron, Guyana, by the Arawaks. -

Representations of Holiness and the Sacred in Latvian Folklore and Folk Belief1

No 6 FORUM FOR ANTHROPOLOGY AND CULTURE 144 Svetlana Ryzhakova Representations of Holiness and the Sacred in Latvian Folklore and Folk Belief1 In fond memory of my teacher, Vladimir Nikolaevich Toporov The term svēts, meaning ‘holy, sacred’ and its derivatives svētums (‘holiness’, ‘shrine/sacred place’), svētība (‘blessing’, ‘paradise’), svētlaime (‘bliss’), svētīt (‘to bless’, ‘to celebrate’), and svētīgs (‘blessed’, ‘sacred’) comprise an im- portant lexical and semantic field in the Latvian language. These lexemes are regularly en- countered in even the earliest Latvian texts, beginning in the 16th century,2 and are no less frequent in Baltic hydronomy and toponymy, as well as in folklore and colloquial speech. According to fairly widespread opinion, the lexeme svēts in Latvian is a loanword from the Svetlana Ryzhakova 13th-century Old Church Slavonic word svyat Institute of Ethnology [holy] (OCS — *svēts, svyatoi in middle Russian, and Anthropology from the reconstructible Indo-European of the Russian Academy 3 of Sciences, Moscow *ђ&en-) [Endzeīns, Hauzenberga 1934–46]. 1 This article is based on the work for the research project ‘A Historical Recreation of the Structures of Latvian Ethnic Culture’, supported by grant no. 06-06-80278 from the Russian Foundation for Basic Research, as well as the Programme for Basic Research of the Presidium of the Russian Academy of Sci- ences ‘The Adaptation of Nations and Cultures to Environmental Changes and Social and Anthropo- genic Transformations’ on the theme ‘The Evolution of the Ethnic and Cultural Image of Europe under the Infl uence of Migrational Processes and the Modernisation of Society’. 2 See [CC 1585: 248]; [Enchiridon 1586: 11]; [Mancelius 1638: 90]; [Fürecher II: 469]. -

The Saeima (Parliament) Election

/pub/public/30067.html Legislation / The Saeima Election Law Unofficial translation Modified by amendments adopted till 14 July 2014 As in force on 19 July 2014 The Saeima has adopted and the President of State has proclaimed the following law: The Saeima Election Law Chapter I GENERAL PROVISIONS 1. Citizens of Latvia who have reached the age of 18 by election day have the right to vote. (As amended by the 6 February 2014 Law) 2.(Deleted by the 6 February 2014 Law). 3. A person has the right to vote in any constituency. 4. Any citizen of Latvia who has reached the age of 21 before election day may be elected to the Saeima unless one or more of the restrictions specified in Article 5 of this Law apply. 5. Persons are not to be included in the lists of candidates and are not eligible to be elected to the Saeima if they: 1) have been placed under statutory trusteeship by the court; 2) are serving a court sentence in a penitentiary; 3) have been convicted of an intentionally committed criminal offence except in cases when persons have been rehabilitated or their conviction has been expunged or vacated; 4) have committed a criminal offence set forth in the Criminal Law in a state of mental incapacity or a state of diminished mental capacity or who, after committing a criminal offence, have developed a mental disorder and thus are incapable of taking or controlling a conscious action and as a result have been subjected to compulsory medical measures, or whose cases have been dismissed without applying such compulsory medical measures; 5) belong