Tobacco Reborn: the Rise of E-Cigarettes and Regulatory Approaches

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Electronic (E-) Cigarettes and Secondhand Aerosol

Defending your right to breathe smokefree air since 1976 Electronic (e-) Cigarettes and Secondhand Aerosol “If you are around somebody who is using e-cigarettes, you are breathing an aerosol of exhaled nicotine, ultra-fine particles, volatile organic compounds, and other toxins,” Dr. Stanton Glantz, Director for the Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education at the University of California, San Francisco. Current Legislative Landscape As of January 2, 2014, 108 municipalities and three states include e-cigarettes as products that are prohibited from use in smokefree environments. Constituents of Secondhand Aerosol E-cigarettes do not just emit “harmless water vapor.” Secondhand e-cigarette aerosol (incorrectly called vapor by the industry) contains nicotine, ultrafine particles and low levels of toxins that are known to cause cancer. E-cigarette aerosol is made up of a high concentration of ultrafine particles, and the particle concentration is higher than in conventional tobacco cigarette smoke.1 Exposure to fine and ultrafine particles may exacerbate respiratory ailments like asthma, and constrict arteries which could trigger a heart attack.2 At least 10 chemicals identified in e-cigarette aerosol are on California’s Proposition 65 list of carcinogens and reproductive toxins, also known as the Safe Drinking Water and Toxic Enforcement Act of 1986. The compounds that have already been identified in mainstream (MS) or secondhand (SS) e-cigarette aerosol include: Acetaldehyde (MS), Benzene (SS), Cadmium (MS), Formaldehyde (MS,SS), Isoprene (SS), Lead (MS), Nickel (MS), Nicotine (MS, SS), N-Nitrosonornicotine (MS, SS), Toluene (MS, SS).3,4 E-cigarettes contain and emit propylene glycol, a chemical that is used as a base in e- cigarette solution and is one of the primary components in the aerosol emitted by e-cigarettes. -

Fiscal Year 2003 Agency Financial Report

Report on Performance and Accountability Table of Contents 4 Management Discussion & Analysis 5 Secretary’s Message 8 Mission, Vision and Organization 9 Executive Summary 24 Annual Performance Report 25 Strategic Goal 1: A Prepared Workforce 27 Outcome Goal 1.1 – Increase Employment, Earnings, and Assistance 49 Outcome Goal 1.2 – Increase the Number of Youth Making A Successful Transition to Work 61 Outcome Goal 1.3 – Improve the Effectiveness of Information and Analysis On The U.S. Economy 69 Strategic Goal 2: A Secure Workforce 71 Outcome Goal 2.1 – Increase Compliance With Worker Protection Laws 81 Outcome Goal 2.2 – Protect Worker Benefits 99 Outcome Goal 2.3 – Increase Employment and Earnings for Retrained Workers 107 Strategic Goal 3: Quality Workplaces 109 Outcome Goal 3.1 – Reduce Workplace Injuries, Illnesses, and Fatalities 127 Outcome Goal 3.2 – Foster Equal Opportunity Workplaces 135 Outcome Goal 3.3 – Reduce Exploitation of Child Labor and Address Core International Labor Standards Issues 143 Departmental Management Goals 145 Outcome Goal HR – Establish DOL as a Model Workplace 153 Outcome Goal PR – Improve Procurement Management 158 Outcome Goal FM – Enhance Financial Performance through Improved Accountability 163 Outcome Goal IT – Provide Better and More Secure Service to Citizens, Businesses, Government, and DOL Employees to Improve Mission Performance 168 Financial Performance Report 169 Chief Financial Officer’s Letter 171 Management of DOL’s Financial Resources 171 Chief Financial Officers Act (CFOA) 172 Inspector General -

© 2014 Alejandro Jose Gomez-Del-Moral ALL RIGHTS

© 2014 Alejandro Jose Gomez-del-Moral ALL RIGHTS RESERVED BUYING INTO CHANGE: CONSUMER CULTURE AND THE DEPARTMENT STORE IN THE TRANSFORMATION(S) OF SPAIN, 1939-1982 By ALEJANDRO JOSE GOMEZ-DEL-MORAL A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in History Written under the direction of Temma Kaplan And approved by ________________________________ ________________________________ ________________________________ ________________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey October 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Buying Into Change: Consumer Culture and the Department Store in the Transformation(s) of Spain, 1939-1982 by ALEJANDRO JOSE GOMEZ-DEL-MORAL Dissertation Director: Temma Kaplan This dissertation examines how the development of a mass consumer society during the dictatorship of Generalissimo Francisco Franco (1939-1975) inserted Spain into transnational consumer networks and drove its democratization. As they spread, Spain’s first modern department stores, supermarkets, consumer magazines, and advertising helped create a public sphere when the Franco regime had curtailed opportunities for public life. In these stores, Spanish consumers encountered foreign products and lifestyles that signaled cosmopolitanism and internationalism, undermining the dictatorship’s foundational discourse of Spanish exceptionalism. With these products came subversive ideas on issues like gender equality, -

NURS 4341.561 Cultural and Spirituality in Nursing

Summer 2021 Summer 2021 NURS 4341.561 Cultural and Spirituality in Nursing Belinda Deal, RN, PhD, CNE Office: BRB 2085 Office Hours: Online and by appointment Email: [email protected] - Preferred method of communication Phone: 903-566-7120 (work phone that will record a message in my email) 903-530-3787 Julie George, PhD, RN Office: PMH 118 Office Hours: Online and by appointment Email: [email protected] - Preferred method of communication Phone: 936-208-9418 Page 1 of 9 Updated 9/30/2020 BKH Summer 2021 Course Description This course will explore major world cultures and concepts of spirituality. Emphasis will be on the healthcare team and interaction with patients/clients. Why students should take this course: Increase understanding of a variety of cultures and belief systems in order to provide better holistic care. Course Learning Objectives Upon successful completion of this course, the student will be able to: 1. Patient Centered Care: Recognize individual’s preferences, values, and needs; anticipate the uniqueness of all individuals, families, and populations; and incorporate the patient/family/population in the plan and implementation of care. 2. Evidence Based Practice: Synthesize and apply evidence, along with clinical expertise and patient values, to improve patient outcomes related to cultural and spiritual values. 3. Teamwork and Collaboration: Function effectively in nursing and interprofessional teams and foster communication, mutual respect, and shared decision-making to achieve quality patient care. 4. Wellness and Prevention: Assess health and wellness in individuals, families, groups, communities, and populations to promote health outcomes. Grading Policy and Criteria Specific guidelines and grading criteria for all assignments are in the Modules. -

VUU Student Handbook Is Distributed to New Students Via QR Code During New Student Orientation and Sent to All Students by VUU Email

1 | P a g e VIRGINIA UNION UNIVERSITY Founded in 1865 Richmond, Virginia AUTHORITY FOR THE STUDENT ANDBOOK The Virginia Union University Student Handbook describes the general rules, regulations, and procedures for student life at the University, and the means by which students may access the full scope of the University’s resources and facilities. The Student Handbook must be used as a companion document to the University Catalog and other published regulations and guidelines issued by various offices and programs of the University. The student, upon admission to the University, obligates himself or herself to adhere to the rules and regulations outlined in this document, the University Catalog, and other published regulations and guidelines that inform both on and off-campus expectations. Virginia Union University also reserves the right to revise, alter, or eliminate the rules and regulations as needed. Students will be informed of such changes by way of VUU email, the official mode of communication for the University. A copy of the VUU Student Handbook is distributed to new students via QR code during New Student Orientation and sent to all students by VUU email. This important document is also available on the VUU website. https://www.vuu.edu/vuu-student-handbook VUU does not discriminate based on race, gender, color, religion, national origin, age, disability, or veteran status in providing educational or employment opportunities or benefits. VUU also embraces and encourages student participation in policy development. 2 | P a g e Letter from the Vice President for Student Development & Success Dear Students of Virginia Union University, To each of you, I extend a warm and sincere Panther Welcome! As a Virginia Union University (VUU) student, you are members of a 155-year legacy and poised to chart your own course. -

Open PDF File, 8.71 MB, for February 01, 2017 Appendix In

Case 4:16-cv-00469-K Document 175 Filed 02/01/17 Page 1 of 10 PageID 5923 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS FORT WORTH DIVISION EXXON MOBIL CORPORATION, § § Plaintiff, § v. § No. 4:16-CV-469-K § ERIC TRADD SCHNEIDERMAN, § Attorney General of New York, in his § official capacity, and MAURA TRACY § HEALEY, Attorney General of § Massachusetts, in her official capacity, § § Defendants. § APPENDIX IN SUPPORT OF EXXON MOBIL CORPORATION’S BRIEF IN SUPPORT OF THIS COURT’S PERSONAL JURISDICTION OVER THE DEFENDANTS Exhibit Description Page(s) N/A Declaration of Justin Anderson (Feb. 1, 2017) v – ix A Transcript of the AGs United for Clean Power App. 1 –App. 21 Press Conference, held on March 29, 2016, which was prepared by counsel based on a video recording of the event. The video recording is available at http://www.ag.ny.gov/press- release/ag-schneiderman-former-vice-president- al-gore-and-coalition-attorneys-general-across B E-mail from Wendy Morgan, Chief of Public App. 22 – App. 32 Protection, Office of the Vermont Attorney General to Michael Meade, Director, Intergovernmental Affairs Bureau, Office of the New York Attorney General (Mar. 18, 2016, 6:06 PM) C Union of Concerned Scientists, Peter Frumhoff, App. 33 – App. 37 http://www.ucsusa.org/about/staff/staff/peter- frumhoff.html#.WI-OaVMrLcs (last visited Jan. 20, 2017, 2:05 PM) Case 4:16-cv-00469-K Document 175 Filed 02/01/17 Page 2 of 10 PageID 5924 Exhibit Description Page(s) D Union of Concerned Scientists, Smoke, Mirrors & App. -

University of California San Francisco

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SAN FRANCISCO BERKELEY • DAVIS • IRVINE • LOS ANGELES • MERCED • RIVERSIDE • SAN DIEGO • SAN FRANCISCO SANTA BARBARA • SANTA CRUZ STANTON A. GLANTZ, PhD 530 Parnassus Suite 366 Professor of Medicine (Cardiology) San Francisco, CA 94143-1390 Truth Initiative Distinguished Professor of Tobacco Control Phone: (415) 476-3893 Director, Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education Fax: (415) 514-9345 [email protected] December 20, 2017 Tobacco Products Scientific Advisory Committee c/o Caryn Cohen Office of Science Center for Tobacco Products Food and Drug Administration Document Control Center Bldg. 71, Rm. G335 10903 New Hampshire Ave. Silver Spring, MD 20993–0002 [email protected] Re: 82 FR 27487, Docket no. FDA-2017-D-3001-3002 for Modified Risk Tobacco Product Applications: Applications for IQOS System With Marlboro Heatsticks, IQOS System With Marlboro Smooth Menthol Heatsticks, and IQOS System With Marlboro Fresh Menthol Heatsticks Submitted by Philip Morris Products S.A.; Availability Dear Committee Members: We are submitting the 10 public comments that we have submitted to the above-referenced docket on Philip Morris’s modified risk tobacco product applications (MRTPA) for IQOS. It is barely a month before the meeting and the docket on IQOS has not even closed. As someone who has served and does serve on committees similar to TPSAC, I do not see how the schedule that the FDA has established for TPSAC’s consideration of this application can permit a responsible assessment of the applications and associated public comments. I sincerely hope that you will not be pressed to make any recommendations on the IQOS applications until the applications have been finalized, the public has had a reasonable time to assess the applications, and TPSAC has had a reasonable time to digest both the completed applications and the public comments before making any recommendation to the FDA. -

Public Health Chronicles

Public Health Chronicles TOBACCO INDUSTRY bacco industry to manipulate information on the risks of MANIPULATION OF RESEARCH tobacco (Figure). These strategies have remained remark- ably constant since the early 1950s. During the 1950s and Lisa A. Bero, PhD 1960s, the tobacco industry focused on refuting data on the adverse effects of active smoking. The industry applied the Research findings provide the basis for estimates of risk. tools it had developed during this time to refute data on However, research findings or “facts” are subject to interpre- the adverse effects of secondhand smoke exposure from the tation and to the social construction of the evidence.1 Re- 1970s through the 1990s. search evidence has a context. The roles of framing, problem The release of previously secret internal tobacco industry definition, and choice of language influence risk communi- documents as a result of the Master Settlement Agreement cation.2 Since data do not “speak for themselves,” interest in 1998 has given the public health community insight into groups can play a critical role in creating and communicat- the tobacco industry’s motives, strategies, tactics, and data.16 ing the research evidence on risk. These documents show that for decades the industry has An interest group is an organized group with a narrowly tried to generate controversy about the health risks of its defined viewpoint, which protects its position or profits.3 products. The internal documents also reveal how the in- These groups are not exclusively business groups, but can dustry has been concerned about maintaining its credibility include all kinds of organizations that may attempt to influ- as it has manipulated research on tobacco.16 ence government.4,5 Interest groups can be expected to con- The tobacco industry has explicitly stated its goal of gen- struct the evidence about a health risk to support their erating controversy about the health risks of tobacco. -

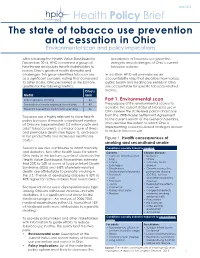

Health Policy Brief the State of Tobacco Use Prevention and Cessation in Ohio Environmental Scan and Policy Implications

June 2015 Health Policy Brief The state of tobacco use prevention and cessation in Ohio Environmental scan and policy implications After releasing the Health Value Dashboard in prevalence of tobacco use given the December 2014, HPIO convened a group of strengths and challenges of Ohio’s current healthcare and public health stakeholders to tobacco policies. review Ohio’s greatest health strengths and challenges. This group identified tobacco use In addition, HPIO will soon release an as a significant concern, noting that compared accountability map that describes how various to other states, Ohio performed in the bottom public health and healthcare entities in Ohio quartile for the following metrics: are accountable for specific tobacco-related Ohio’s metrics. Metric rank Adult cigarette smoking 44 Part 1. Environmental scan Secondhand smoke exposure for children 49 The purpose of this environmental scan is to describe the current status of tobacco use in Tobacco prevention and control spending 46 Ohio, review the state-level policy landscape Tobacco use is highly relevant to state health from the 1998 Master Settlement Agreement policy because it impacts a significant number to the current session of the General Assembly, of Ohioans (approximately 2.2 million youth and and describe the extent to which Ohio is adult tobacco users1), is a major cause of illness implementing evidence-based strategies proven and premature death (see Figure 1), and results to reduce tobacco use. in lost productivity and increased healthcare Figure 1. Health consequences of costs.2 smoking and secondhand smoke Tobacco use also contributes to infant mortality Conditions causally linked to smoking and diabetes, two other health issues for which Cancers Chronic diseases Ohio ranks in the bottom quartile of states on the • Trachea, bronchus and • Diabetes Health Value Dashboard. -

Cigars Were Consumed Last Year (1997) in the United States

Smoking and Tobacco Control Monograph No. 9 Preface The recent increase in cigar consumption began in 1993 and was dismissed by many in public health as a passing fad that would quickly dissipate. Recently released data from the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) suggests that the upward trend in cigar use might not be as temporary as some had predicted. The USDA now projects a total of slightly more than 5 billion cigars were consumed last year (1997) in the United States. Sales of large cigars, which comprise about two-thirds of the total U.S. cigar market, increased 18 percent between 1996 and 1997. Consumption of premium cigars (mostly imported and hand-made) increased even more, an astounding 90 percent last year and an estimated 250 percent since 1993. In contrast, during this same time period, cigarette consumption declined 2 percent. This dramatic change in tobacco use raises a number of public health questions: Who is using cigars? What are the health risks? Are premium cigars less hazardous than regular cigars? What are the risks if you don't inhale the smoke? What are the health implications of being around a cigar smoker? In order to address these questions, the National Cancer Institute (NCI) undertook a complete review of what is known about cigar smoking and is making this information available to the American public. This monograph, number 9 in a series initiated by NCI in 1991, is the work of over 50 scientists both within and outside the Federal Government. Thirty experts participated in the multi-stage peer review process (see acknowledgments). -

The Development and Evaluation of Effective Symbol Signs

NBS BUILDING SCIENCE SERIES 141 The Development and Evaluation of Effective Symbol Signs TA 435 .U58 NO, 141 ^RTMENT OF COMMERCE • NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS c. 2 NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS The National Bureau of Standards' was established by an act of Congress on March 3, 1901. The Bureau's overall goal is to strengthen and advance the Nation's science and technology and facilitate their effective application for public benefit. To this end, the Bureau conducts research and provides: (1) a basis for the Nation's physical measurement system, (2) scientific and technological services for industry and government, (3) a technical basis for equity in trade, and (4) technical services to promote public safety. The Bureau's technical work is per- formed by the National Measurement Laboratory, the National Engineering Laboratory, and the Institute for Computer Sciences and Technology. THE NATIONAL MEASUREMENT LABORATORY provides the national system of physical and chemical and materials measurement; coordinates the system with measurement systems of other nations and furnishes essential services leading to accurate and uniform physical and chemical measurement throughout the Nation's scientific community, industry, and commerce; conducts materials research leading to improved methods of measurement, standards, and data on the properties of materials needed by industry, commerce, educational institutions, and Government; provides advisory and research services to other Government agencies; develops, produces, and distributes Standard Reference -

Pdf Smoking Cessation Brochure

Online Quit Guides & Resources Who We Are American Cancer Society (ACS): To speak to a quit specialist: 1(800) 227-2345 Tobacco-Free Guide to Quitting Smoking: www.cancer.org TFC Coalition American Lung Association in Ohio: Vision: We envision a region free of tobacco use. Freedom from Smoking (FFS) • (513) 985-3990 Mission: Our mission is to promote healthy lives • FFS Clinic: Provided by onsite facilitator free of tobacco in all its forms by: - fee determined by class size and location • FFS Online: www.ffsonline.org • Reducing tobacco use - free option available • Keeping people from starting tobacco use • FFS Facilitator Training - $350 - various location training sites • Educating the public about tobacco-related • Lung HelpLine: 1-800-586-4872 - free health issues • Fee varies by program. • Supporting those who want to quit LGBT Landing Page / Smokefree.gov: • Advocating for positive reform http://smokefree.gov/lgbt-and-smoking Use an App to Quit. QuitSTART is a free app that gives you TFC is a network of organizations, businesses and tips, inspiration, and challenges so you can live as the true individuals who are building support for tobacco you, tobacco-free. prevention and control in the Miami Valley. National Cancer Institute: If you would like to join TFC or receive more Cessation information: www.smokefree.gov information, please contact: Teenage Smoking: Montgomery County Tobacco-Free Coalition Teen smoking: How to help your teen quit. c/o Public Health Dayton & Montgomery County teen.smokefree.gov 117 South Main Street, Dayton, OH 45422 The American Legacy Association: (937) 225-4398 • www.phdmc.org Tobacco Cessation www.becomeanex.org The EX Plan is a free quit smoking program that helps Services in you re-learn life without cigarettes.