Health Policy Brief the State of Tobacco Use Prevention and Cessation in Ohio Environmental Scan and Policy Implications

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Electronic (E-) Cigarettes and Secondhand Aerosol

Defending your right to breathe smokefree air since 1976 Electronic (e-) Cigarettes and Secondhand Aerosol “If you are around somebody who is using e-cigarettes, you are breathing an aerosol of exhaled nicotine, ultra-fine particles, volatile organic compounds, and other toxins,” Dr. Stanton Glantz, Director for the Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education at the University of California, San Francisco. Current Legislative Landscape As of January 2, 2014, 108 municipalities and three states include e-cigarettes as products that are prohibited from use in smokefree environments. Constituents of Secondhand Aerosol E-cigarettes do not just emit “harmless water vapor.” Secondhand e-cigarette aerosol (incorrectly called vapor by the industry) contains nicotine, ultrafine particles and low levels of toxins that are known to cause cancer. E-cigarette aerosol is made up of a high concentration of ultrafine particles, and the particle concentration is higher than in conventional tobacco cigarette smoke.1 Exposure to fine and ultrafine particles may exacerbate respiratory ailments like asthma, and constrict arteries which could trigger a heart attack.2 At least 10 chemicals identified in e-cigarette aerosol are on California’s Proposition 65 list of carcinogens and reproductive toxins, also known as the Safe Drinking Water and Toxic Enforcement Act of 1986. The compounds that have already been identified in mainstream (MS) or secondhand (SS) e-cigarette aerosol include: Acetaldehyde (MS), Benzene (SS), Cadmium (MS), Formaldehyde (MS,SS), Isoprene (SS), Lead (MS), Nickel (MS), Nicotine (MS, SS), N-Nitrosonornicotine (MS, SS), Toluene (MS, SS).3,4 E-cigarettes contain and emit propylene glycol, a chemical that is used as a base in e- cigarette solution and is one of the primary components in the aerosol emitted by e-cigarettes. -

Tobacco Reborn: the Rise of E-Cigarettes and Regulatory Approaches

LCB_25_3_Article_3_Aaron (Do Not Delete) 8/6/2021 9:26 AM TOBACCO REBORN: THE RISE OF E-CIGARETTES AND REGULATORY APPROACHES by Dr. Daniel G. Aaron* This Article examines e-cigarettes, FDA-regulated products which heat nico- tine-containing fluid into an aerosol to be breathed into the lungs. Recent data show that e-cigarettes are used by about one-fifth of U.S. high school students. Given that we have, in the Surgeon General’s words, reached an epidemic of youth e-cigarette use, it is worth asking how a product within FDA jurisdic- tion became a serious threat to 3.6 million youth. This Article reviews the law surrounding e-cigarettes and the history of FDA’s attempts to regulate them. Administrative law doctrines instruct us that in- creased presidential control will rein in misbehaving agencies by allowing the people to vote out a president who improperly directs the administrative state. However, e-cigarettes present a potent counterexample. On multiple occasions, presidential control over FDA stymied essential tobacco regulations by increas- ing the influence of the tobacco industry over expert agency policymaking. Yet children harmed by these tobacco policies have no right to vote and little po- litical clout with which to advocate for their interests. Ultimately, the emerg- ing approach to regulating e-cigarettes stands in opposition to a looming his- torical context and a boiling epidemic of nicotine addiction. By painting the context of e-cigarettes in lush detail, drawing from history, law, medicine, and public health, this Article charts a path forward for e-cigarettes and other ad- dicting products. -

Open PDF File, 8.71 MB, for February 01, 2017 Appendix In

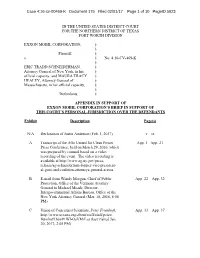

Case 4:16-cv-00469-K Document 175 Filed 02/01/17 Page 1 of 10 PageID 5923 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS FORT WORTH DIVISION EXXON MOBIL CORPORATION, § § Plaintiff, § v. § No. 4:16-CV-469-K § ERIC TRADD SCHNEIDERMAN, § Attorney General of New York, in his § official capacity, and MAURA TRACY § HEALEY, Attorney General of § Massachusetts, in her official capacity, § § Defendants. § APPENDIX IN SUPPORT OF EXXON MOBIL CORPORATION’S BRIEF IN SUPPORT OF THIS COURT’S PERSONAL JURISDICTION OVER THE DEFENDANTS Exhibit Description Page(s) N/A Declaration of Justin Anderson (Feb. 1, 2017) v – ix A Transcript of the AGs United for Clean Power App. 1 –App. 21 Press Conference, held on March 29, 2016, which was prepared by counsel based on a video recording of the event. The video recording is available at http://www.ag.ny.gov/press- release/ag-schneiderman-former-vice-president- al-gore-and-coalition-attorneys-general-across B E-mail from Wendy Morgan, Chief of Public App. 22 – App. 32 Protection, Office of the Vermont Attorney General to Michael Meade, Director, Intergovernmental Affairs Bureau, Office of the New York Attorney General (Mar. 18, 2016, 6:06 PM) C Union of Concerned Scientists, Peter Frumhoff, App. 33 – App. 37 http://www.ucsusa.org/about/staff/staff/peter- frumhoff.html#.WI-OaVMrLcs (last visited Jan. 20, 2017, 2:05 PM) Case 4:16-cv-00469-K Document 175 Filed 02/01/17 Page 2 of 10 PageID 5924 Exhibit Description Page(s) D Union of Concerned Scientists, Smoke, Mirrors & App. -

University of California San Francisco

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SAN FRANCISCO BERKELEY • DAVIS • IRVINE • LOS ANGELES • MERCED • RIVERSIDE • SAN DIEGO • SAN FRANCISCO SANTA BARBARA • SANTA CRUZ STANTON A. GLANTZ, PhD 530 Parnassus Suite 366 Professor of Medicine (Cardiology) San Francisco, CA 94143-1390 Truth Initiative Distinguished Professor of Tobacco Control Phone: (415) 476-3893 Director, Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education Fax: (415) 514-9345 [email protected] December 20, 2017 Tobacco Products Scientific Advisory Committee c/o Caryn Cohen Office of Science Center for Tobacco Products Food and Drug Administration Document Control Center Bldg. 71, Rm. G335 10903 New Hampshire Ave. Silver Spring, MD 20993–0002 [email protected] Re: 82 FR 27487, Docket no. FDA-2017-D-3001-3002 for Modified Risk Tobacco Product Applications: Applications for IQOS System With Marlboro Heatsticks, IQOS System With Marlboro Smooth Menthol Heatsticks, and IQOS System With Marlboro Fresh Menthol Heatsticks Submitted by Philip Morris Products S.A.; Availability Dear Committee Members: We are submitting the 10 public comments that we have submitted to the above-referenced docket on Philip Morris’s modified risk tobacco product applications (MRTPA) for IQOS. It is barely a month before the meeting and the docket on IQOS has not even closed. As someone who has served and does serve on committees similar to TPSAC, I do not see how the schedule that the FDA has established for TPSAC’s consideration of this application can permit a responsible assessment of the applications and associated public comments. I sincerely hope that you will not be pressed to make any recommendations on the IQOS applications until the applications have been finalized, the public has had a reasonable time to assess the applications, and TPSAC has had a reasonable time to digest both the completed applications and the public comments before making any recommendation to the FDA. -

Public Health Chronicles

Public Health Chronicles TOBACCO INDUSTRY bacco industry to manipulate information on the risks of MANIPULATION OF RESEARCH tobacco (Figure). These strategies have remained remark- ably constant since the early 1950s. During the 1950s and Lisa A. Bero, PhD 1960s, the tobacco industry focused on refuting data on the adverse effects of active smoking. The industry applied the Research findings provide the basis for estimates of risk. tools it had developed during this time to refute data on However, research findings or “facts” are subject to interpre- the adverse effects of secondhand smoke exposure from the tation and to the social construction of the evidence.1 Re- 1970s through the 1990s. search evidence has a context. The roles of framing, problem The release of previously secret internal tobacco industry definition, and choice of language influence risk communi- documents as a result of the Master Settlement Agreement cation.2 Since data do not “speak for themselves,” interest in 1998 has given the public health community insight into groups can play a critical role in creating and communicat- the tobacco industry’s motives, strategies, tactics, and data.16 ing the research evidence on risk. These documents show that for decades the industry has An interest group is an organized group with a narrowly tried to generate controversy about the health risks of its defined viewpoint, which protects its position or profits.3 products. The internal documents also reveal how the in- These groups are not exclusively business groups, but can dustry has been concerned about maintaining its credibility include all kinds of organizations that may attempt to influ- as it has manipulated research on tobacco.16 ence government.4,5 Interest groups can be expected to con- The tobacco industry has explicitly stated its goal of gen- struct the evidence about a health risk to support their erating controversy about the health risks of tobacco. -

Heated Tobacco Products This Episode Is De

Episode Details: Date of Publication: July 28, 2020 Title: Episode 18: Heated Tobacco Products Description: This episode is designed to answer all your questions about heated tobacco products, or as the industry refers to them, "heat-not-burn" products. This episode covers their design and safety, assesses their marketing and current regulation, examines a bit of the newer research and literature on the products, explains the FDA's 'modified risk' label authorization for the IQOS Heated Tobacco System, and considers policy options moving forward. Transcription: I'm Allie Rothschild and you're listening to the Counter Tobacco Podcast. You may be hearing a lot more this month than usual about heated tobacco products. That's because the Food and Drug Administration just announced a monumental decision on how one of these products, the IQOS heated tobacco system, can be marketed here in the United States. But before we dive deeper into this, I want to start at the beginning and cover some of the basics. What are heated tobacco products? Are they really safer than cigarettes? What’s all this news with the FDA? This episode is designed to answer all your questions on heated tobacco products, or HTPs. We'll look at their design and safety, assess their marketing and current regulation, examine a bit of the newer research and literature on the products, and consider policy options moving forward. So, foremost, what are and are not heated tobacco products? The most basic definition of a heated tobacco product is an electronic device that heats tobacco which produces an aerosol inhaled by the user. -

TEA Party Exposed by ANONYMOUS Political Party

ANONYMOUS Political Party would like to take the pleasure to introduce The TEA Party /// Tobacco Everywhere Always this DOX will serve as a wake-up call to some people in the Tea Party itself … who will find it a disturbing to know the “grassroots” movement they are so emotionally attached to, is in fact a pawn created by billionaires and large corporations with little interest in fighting for the rights of the common person, but instead using the common person to fight for their own unfettered profits. The “TEA Party” drives a wedge of division in America | It desires patriots, militias, constitutionalists, and so many more groups and individuals to ignite a revolution | to destroy the very fabric of the threads which were designed to kept this republic united | WE, will not tolerate the ideologies of this alleged political party anymore, nor, should any other individual residing in this nation. We will NOT ‘Hail Hydra”! United as One | Divided by Zero ANONYMOUS Political Party | United States of America www.anonymouspoliticalparty.org Study Confirms Tea Party Was Created by Big Tobacco and Billionaires Clearing the PR Pollution That Clouds Climate Science Select Language ▼ FOLLOW US! Mon, 2013-02-11 00:44 BRENDAN DEMELLE SUBSCRIBE TO OUR E- Study Confirms Tea Party Was Created by Big NEWSLETTER Get our Top 5 stories in your inbox Tobacco and Billionaires weekly. A new academic study confirms that front 12k groups with longstanding ties to the tobacco industry and the billionaire Koch Like DESMOG TIP JAR brothers planned the formation of the Tea Help us clear the PR pollution that Party movement more than a decade clouds climate science. -

The Tobacco Industry's Successful Efforts to Control Tobacco Policy

The Tobacco Industry’s Successful Efforts to Control Tobacco Policy Making in Switzerland Chung-Yol Lee, MD MPH Stanton A. Glantz, PhD Division of Adolescent Medicine Department of Pediatrics Institute for Health Policy Studies School of Medicine University of California, San Francisco San Francisco CA 94143 January 2001 The Tobacco Industry’s Successful Efforts to Control Tobacco Policy Making in Switzerland Chung-Yol Lee, MD MPH Stanton A. Glantz, PhD Division of Adolescent Medicine Department of Pediatrics Institute for Health Policy Studies School of Medicine University of California, San Francisco San Francisco CA 94143 January 2001 Supported in part by Swiss National Science Foundation Grant 823B-053423 to the first author and National Cancer Institute Grants CA-61021 and CA-87482, American Cancer Society Grant CCG-294, and a grant from the Richard and Rhoda Goldman Fund to the second author. This report was prepared in response to a request from the World Health Organization Tobacco Free Initiative. Opinions expressed reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent any sponsoring agency, the WHO, or the Division of Adolescent Medicine or the Institute for Health Policy Studies at the University of California. Copyright 2000 by Chung-Yol Lee and Stanton Glantz. This report is available on the World Wide Web at http://www.library.ucsf.edu/tobacco/swiss. (5/28/01 correction) This report is the latest in a series of reports that analyze tobacco industry campaign contributions, lobbying, and other political activity. The previous reports are: M. Begay and S. Glantz. Political Expenditures by the Tobacco Industry in California State Politics UCSF IHPS Monograph Series, 1991. -

Stanton A. Glantz Papers MSS.97.08

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8wq086t No online items Stanton A. Glantz Papers MSS.97.08 David Krah University of California, San Francisco Archives & Special Collections 530 Parnassus Ave Room 524 San Francisco, CA 94143-0840 415-476-8112 [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucsf.edu/collections/archives Stanton A. Glantz Papers MSS.97.08 1 MSS.97.08 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: University of California, San Francisco Archives & Special Collections Title: Stanton A. Glantz Papers creator: Glantz, Stanton A. Identifier/Call Number: MSS.97.08 Physical Description: 12.5 Linear Feet(7 cartons, 12 boxes) Date (inclusive): 1983-2012 Biographical note Stanton Arnold Glantz is a professor in the Department of Medicine, School of Medicine, at the University of California, San Francisco, and a well-known anti-tobacco activist and writer. In 1994, Glantz donated to the UCSF Tobacco Control Archives his research files based on copies of internal tobacco industry documents, which are known as the Brown & Williamson Collection. He co-authored with John Slade, Lisa A. Bero, Peter Hanauer, and Deborah E. Barnes The Cigarette Papers (Berkeley: University of California Press, c1996) and Tobacco War: Inside the California Battles (Berkeley: University of California Press, c.2000) with Edith D. Balbach. Glantz has written numerous articles based on the Brown & Williamson industry documents and co-wrote a series of reports on the tobacco industry and anti-tobacco activities around the country. Glantz received a Ph.D. in Applied Mechanics/Engineering-Economic Systems from Stanford University in 1973 and stayed at Stanford as a Research Fellow in Cardiology. -

Avoiding •Œtruthâ•Š: Tobacco Industry Promotion of Life Skills Training

UCSF Postprints from the CTCRE Title Avoiding “Truth”: Tobacco Industry Promotion of Life Skills Training Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2cd8t2jd Journal Journal of Adolescent Health, epub ahead of print Authors Bialous, Stella Aguinaga Mandel, Lev L. Glantz, Stanton A., Ph.D. Publication Date 2006 DOI doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.06.010 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California ARTICLE IN PRESS Journal of Adolescent Health xx (2006) xxx–xxx Original article Avoiding “Truth”: Tobacco Industry Promotion of Life Skills Training Lev L. Mandel, M.Sc.a Stella Aguinaga Bialous, Dr.P.H., R.N.b and Stanton A. Glantz, Ph.D.a,* aCenter for Tobacco Control Research and Education, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, California bTobacco Policy International, San Francisco, California Manuscript received March 20, 2006; manuscript accepted June 23, 2006 Abstract: Purpose: To understand why and how two tobacco companies have been promoting the Life Skills Training program (LST), a school-based drug prevention program recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to reduce youth smoking. Methods: We analyzed internal tobacco industry documents available online as of October 2005. Initial searches were conducted using the keywords “life skills training,” “LST,” and “positive youth development.” Results: Tobacco industry documents reveal that since 1999, Philip Morris (PM) and Brown and Williamson (B&W) have worked to promote LST and to disseminate the LST program into schools across the country. As part of their effort, the companies hired a public relations firm to promote LST and a separate firm to evaluate the program. -

Stanton A. Glantz Papers, 1980-97, N.D

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/ft438nb0sz No online items Inventory of the Stanton A. Glantz Papers, 1980-97, n.d. Processed by Julia Bazar; machine-readable finding aid created by Hernán Cortés UCSF Library & CKM Archives and Special Collections 530 Parnassus Ave. San Francisco, CA 94143-0840 Phone: (415) 476-8112 Fax: (415) 476-4653 Email: http://www.library.ucsf.edu/collections/archives/contact URL: http://www.library.ucsf.edu/tobacco/ © 1998 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Note History -- History, California -- GeneralBiological and Medical Sciences -- Public Health -- General Inventory of the Stanton A. MSS 97-08 1 Glantz Papers, 1980-97, n.d. Inventory of the Stanton A. Glantz Papers, 1980-97, n.d. Collection number: MSS 97-08 UCSF Library & Center for Knowledge Management Tobacco Control Archives Archives and Special Collections University of California, San Francisco Contact Information: UCSF Library & CKM Archives and Special Collections 530 Parnassus Ave. San Francisco, CA 94143-0840 Phone: (415) 476-8112 Fax: (415) 476-4653 Email: http://www.library.ucsf.edu/collections/archives/contact URL: http://www.library.ucsf.edu/tobacco/ Processed by: Julia Bazar Date Completed: August 1997 Encoded by: Hernán Cortés © 1998 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Stanton A. Glantz Papers, Date (inclusive): 1980-97, n.d. Collection number: MSS 97-08 Collector: Stanton A. Glantz Extent: Number of containers: 1 box, 1 carton Linear feet: approx. 1.65 Repository: University of California, San Francisco. Library. Archives and Special Collections. San Francisco, California 94143-0840 Shelf location: For current information on the location of these materials, please consult the Library's online catalog Language: English. -

The Economics of Tobacco: Myths and Realities Tob Control: First Published As 10.1136/Tc.9.1.78 on 1 March 2000

78 Tobacco Control 2000;9:78–89 The economics of tobacco: myths and realities Tob Control: first published as 10.1136/tc.9.1.78 on 1 March 2000. Downloaded from Kenneth E Warner Introduction papers, insurance coverage, and transportation Each side in the debate about tobacco and shipping). Excise (and other) tobacco control—the tobacco industry and the public taxation generates many tens of billions of dol- health community—wields a seemingly power- lars annually.2 ful set of economic arguments, the industry Individual countries’ tobacco economies claiming that economic considerations urge a vary greatly. Nearly half of the world’s tobacco “go slow” approach to tobacco control, the farmers (an estimated 15 million) live in public health community insisting they recom- China, the world’s largest producer and mend an aggressive stance. Each of the most consumer of tobacco; 3.5 million reside in prominent arguments presented by both sides India. Other countries exhibit substantial has a kernel of truth to it; yet each, in its own tobacco sectors as well, including Zimbabwe, way, represents only a half truth. The industry Indonesia, Turkey, Bangladesh, Egypt, the uses its economic appeal with full knowledge of Philippines, and Thailand. These countries are and intent to exploit its ability to deceive and the exceptions to the rule, however. Tobacco mislead policy makers and the public. In farming constitutes a modest source of contrast, tobacco control advocates frequently employment in most countries and tobacco employ their economic rationale without full manufacturing employment constitutes well appreciation of its limitations. To inform both under 1% of total manufacturing employment tobacco control advocates and policy makers in most countries.1 Several countries derive more fully, this paper identifies the principal 10% or more of total government revenues economic myths concerning tobacco and from tobacco taxation.