A Comparative Analysis of African and Punjabi Folklore

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Punjab: History and Culture (January 7-9, 2020)

INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE on The Punjab: History and Culture (January 7-9, 2020) Highlighted Yellow Have not yet submitted full papers for The Punjab: History and Culture (PHC) Highlighted Red were given conditional acceptance and have not submitted revised complete abstracts. Now they are requested to submit complete papers, immediately. Day 1: January 07, 2020 INAUGURAL SESSION 10:00 12:30 Lunch Break: 12:30-13:30 Parallel Session 1, Panel 1: The Punjab: From Antiquity to Modernity Time Paper Title Author’s Name 1 13:30 – 13:40 From Vijayanagara to Maratha Empire: A Multi- Dr. Khushboo Kumari Linear Journey, c. 1500-1700 A. D. 2 13:40 – 13:50 On the Footsteps of Korean Buddhist monk in Dr. Esther Park Pakistan: Reviving the Sacred Ancient Trail of Gandhara 3 13:50 – 14:00 Archiving Porus Rafiullah Khan 4 14:00 – 14:10 Indus Valley Civilization, Harrapan Civilization and Kausar Parveen Khan the Punjab (Ancient Narratives) 5 14:10 – 14:20 Trade Relations of Indus Valley and Mesopotamian Dr. Irfan Ahmed Shaikh Civilizations: An Analytical Appraisal 6 14:20 – 14:30 Image of Guru Nanak : As Depicted in the Puratan Dr. Balwinderjit Kaur Janam Sakhi Bhatti 14:30 – 15:00 Discussion by Chair and Discussant Discussant Chair Moderator Parallel Session 1, Panel 2: The Punjab in Transition Time Paper Title Author’s Name 1 13:30 – 13:40 History of ancient Punjab in the 6th century B. C Nighat Aslam with special reference of kingdom of Sivi and its Geographical division 2 13:40 – 13:50 Living Buddhists of Pakistan: An Ethnographic Aleena Shahid Study -

Sample Page of Text

JPS: 11:2 Chaman & Sawyer: Imagining Life in a Punjabi Village Imagining Life in a Punjabi Village Saroj Chaman Punjabi University Patiala Caroline Sawyer State University of New York College at Old Westbury ______________________________________________________ This article explores the rhythms of traditional Punjabi village life: the ways that Punjabis set up their villages and dwellings and live their lives with a perception of the interrelatedness of the human, natural, and spiritual orders. The article looks at how they eat, celebrate their festivals and break the monotony of their challenging agrarian life style. The article also addresses the potential challenges that the “traditional” village has to deal with in the face of global change. ______________________________________________________ By nature, village activity transcends distinctions, synthesizing the natural and human orders; boundaries of work and play; perspectives of adults and children. Or rather, ideally, it does not synthesize these areas of life, but expresses an awareness of interrelationship that any number of subsequent developments have disrupted: urbanization, division of labor, industrialization, commercialization, globalization. Not least among these disrupting factors would be education and scholarly analysis. Once masses of people are taught to distinguish “high” from “popular” culture, possibilities for naïve production becomes much more restricted. When produced for external consumption— purchase or display outside the home environment—the intimate ties of an artifact to the cosmos, the dwelling, the functions it was intended to serve, and the artisan(s) become broken. The appreciation of folk art by outsiders thus signals the disruption of organicity. The buyer’s pursuit of the folk-artifact’s appeal and economic value; the twinge of the viewer on recognizing a quality she knows she is unable to produce; the urge of the scholar to describe and classify—all have something in common. -

E:\2019\Other Books\Final\Darshan S. Tatla\New Articles\Final Articles.Xps

EXPLORING ISSUES AND PROJECTS FOR COOPERATION BETWEEN EAST AND WEST PUNJAB WORLD PUNJABI CENTRE Monographs and Occasional Papers Series The World Punjabi Centre was established at Punjabi University, Patiala in 2004 at the initiative of two Chief Ministers of Punjabs of India and Pakistan. The main objective of this Centre is to bring together Punjabis across the globe on various common platforms, and promote cooperation across the Wagah border separating the two Punjabs of India and Pakistan. It was expected to have frequent exchange of scholarly meetings where common issues of Punjabi language, culture and trade could be worked out. This Monograph and Occasional Papers Series aims to highlight some of the issues which are either being explored at the Centre or to indicate their importance in promoting an appreciation and understanding of various concerns of Punjabis across the globe. It is hoped other scholars will contribute to this series from their respective different fields. Monographs 1. Exploring Possibilities of Cooperation among Punjabis in the Global Context – (Proceedings of the Conference held in 2006), Edited by J. S. Grewal, Patiala: World Punjabi Centre, 2008, 63pp. 2. Bhagat Singh and his Legend, (Papers Presented at the Conference in 2007) Edited by J. S. Grewal, Patiala: World Punjabi Centre, 2008, 280pp. Occasional Papers Series 1. Exploring Issues and Projects For Cooperation between East and West Punjab, Balkar Singh & Darshan S. Tatla, Patiala: World Punjabi Centre, Occasional Papers Series No. 1, 2019 2. Sikh Diaspora Archives: An Outline of the Project, Darshan S. Tatla & Balkar Singh, Patiala: World Punjabi Centre, Occasional Papers Series No. -

Handlooms in Madras State, Tamilndau

CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 VOLUME IX MADRAS PART XI-A HANDLOOMS IN MADRAS STATE P. K. NAMBIAR of the Indian Administrative Service Superintendent of Census Operations, Madras 1964 CENSUS OF INDIA, 1961 (Census Report-Vol. No. IX will relate to Madras only. Under this series will be issued the following publications) Part I-A General Report I-B Demography and Vital Statistics. I-C Subsidiary Tables .. Part II-A General Population Tables. II-B Economic Tables. II-C Cultural and Migration Taples. Part III Household Economic Tables. Part IV-A Report on Housing and Establishments. IV-B Housing and Establishment Tables. Part V-A Scheduled Castes and Tribes (Report & Tables). V-B Ethnographic notes on Scheduled Tribes. V-C Todas. V-D Ethnographic notes on Scheduled Castes. V-E Ethnographic notes on denotified and nomadic tribes. Part VI Village Survey Monographs (40 Nos.)' Part VII-A Crafts and Artisans. (9 Nos.) VII-B Fairs and Festivals. Part VIII-A Administration Report-Enumeration } For official use only. VIII-B Administration Report-Tabulation Part IX Atlas of the Madras State. Part X Madras City (2· Volumes) District Census Handbooks on twelve districts. Part XI Reports on Special Studies. A Handlooms in Madras State. B Food Habits in Madras State. C Slums of Madras City. D Temples of Madras State (5,Volumes). E Physically Handicapped of Madras State. F F'amily Planning Attitudes: A Survey. Part XU Languages of Madras State. As indicated in my Preface, tbis survey has been made possible by the experience and industry of Sri K. V. Sivasankaran whose earlier acquaintance with the working of the Co.-operative and Textile Departments has been of immeQse value. -

A Comparative Analysis of Translated Punjabi Folk Tale Editions, From

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. Once Upon a Time in the Land of Five Rivers: A Comparative Analysis of Translated Punjabi Folk Tale Editions, from Flora Annie Steel’s Colonial Collection to Shafi Aqeel’s Post-Partition Collection and Beyond A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, in English Literature Massey University, Manawatu Campus, New Zealand Noor Fatima, 2019 i Abstract This thesis offers a critical analysis of two different collections of Punjabi folk tales which were collected at different moments in Punjab’s history: Tales of the Punjab (1894), collected by Flora Annie Steel and, Popular Folk Tales of the Punjab (2008) collected by Shafi Aqeel and translated from Urdu into English by Ahmad Bashir. The study claims that the changes evident in collections of Punjabi folk tales published in the last hundred years reveal the different social, political and ideological assumptions of the collectors, translators and the audiences for whom they were disseminated. Each of these collections have one prior edition that differs in important ways from the later one. Steel’s edition was first published during the late-colonial era in India as Wide- awake Stories in 1884 and consisted of tales that she translated from Punjabi into English. Aqeel’s first edition was collected shortly after the partition of India and Pakistan, as Punjabi Lok Kahaniyan in 1963 and consisted of tales he translated from Punjabi into Urdu. -

Female Agency and Representation in Punjabi Folklore: Reflections on a Folk Song of Rachna Valley

Female Agency and Representation in Punjabi Folklore: Reflections on a Folk song of Rachna Valley Fayyaz Baqir University of Gothenburg, Gothenberg, Sweden This paper is a reflection on a Punjabi love song from Rachna Valley. The theme of the song is true love, which symbolizes the courage to kiss death in the longing to find union with the beloved. This theme invariably depicts love as subversion of patriarchy. It is an act of union with the lover and renunciation of all the barriers of gender, caste and class. The lover in folk tradition—in contrast to the narrative of patriarchy—is invariably female. The story of love plays at various levels; it is negation of vanity, class, and discriminatory norms; and it affirms undying love that transcends all existing bonds. Union with the beloved who is an outcast and belongs to the territory of unknown is only possible by stepping out of the abode of known and living through the pain of separation from the paternal home. The paper provides an in-depth review of how separation from barriers is integrally linked with union with the lover. Love is not only a moment of union but is preceded by moment of separation that completes the dialectical transition from existence to being. Turn back, turn back, my wandering lover,1 turn your eyes to me again Turn back, haven’t I asked you to turn your eyes to me? Turn back (to meet me) in the back lanes of the majesty palaces, Turn back your eyes to me A chained tiger is in the lane, turn back (your eyes) to me A Police Chief has descended (on the lane), turn back (your eyes) to me He asks for my bracelets; turn back your eyes to me He asks for my necklace; turn back your eyes to me With laughter I gave him my bracelets, turn your eyes again to me With cries I gave him my necklace, turn back (my love) your eyes to me Turn back to me, my soul is sad, turn back your eyes to me my love Turn back to me, Turn back to me, my estranged lover. -

Punjabi Folklore “Ballad”

Ad Litteram: An English Journal of International Literati ISSN: 2456 6624 December 2018: Volume 3 PUNJABI FOLKLORE “BALLAD” Sheeba Zafar* The term folk include all those persons living within a given area, who are conscious of a common cultural heritage, and have some common traits e.g. Occupation, languages and religion. The way of life of the group of the people is more traditional, more natural, less systematic and less specialized in comparison to the so called civilized people. The behavioral knowledge is based on oral tradition & not on written scriptures. The group have a sense of identity & belongingness regardless of its numerical strength. According to William Bascom , “folk lore means folk learning which comprehends all meaning that is transmitted by word of mouth and all crafts & techniques that are learnt by imitation or example, as well as the products of these crafts. Folk lore includes folk art folk crafts, folk costumes folk belief folk medicine, folk music, folk dance, folk games folk gestures.” It also includes folk literature with such forms as folk tales, Legends, Ballads, Myths, Epic lays, Proverbs & Riddles, culture, complex traditions & social beliefs. According to Malinowski & Radcliffe Brown-“folklore is a vital element in a living culture”. 197 *Assistant Professor, Al-Baha University, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Ad Litteram: An English Journal of International Literati ISSN: 2456 6624 December 2018: Volume 3 Folklorist Richard A. Waterman says, “Folklore is that art form, comprising various type of stories, proverbs, saying, spells, songs, incantations and many more things, which employs spoken language as its medium”. Charles Francis Potter in his definition states that Folklore is a lively fossil which refuses to die. -

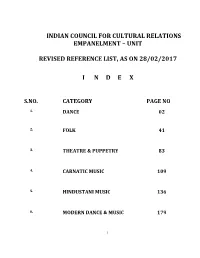

Unit Revised Reference List, As on 28/02/2017 I

INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS EMPANELMENT – UNIT REVISED REFERENCE LIST, AS ON 28/02/2017 I N D E X S.NO. CATEGORY PAGE NO 1. DANCE 02 2. FOLK 41 3. THEATRE & PUPPETRY 83 4. CARNATIC MUSIC 109 5. HINDUSTANI MUSIC 136 6. MODERN DANCE & MUSIC 179 1 INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS EMPANELMEMT SECTION REVISED REFERENCE LIST FOR DANCE - AS ON 28/02/2017 S.NO. CATEGORY PAGE NO 1. BHARATANATYAM 3 – 11 2. CHHAU 12 – 13 3. KATHAK 14 – 20 4. KATHAKALI 21 – 22 5. KRISHNANATTAM 23 6. KUCHIPUDI 24 – 26 7. KUDIYATTAM 27 8. OTTAN THULLAL 28 9. MANIPURI 29 – 30 10. MOHINIATTAM 31– 32 11. ODISSI 33 – 37 12. SATTRIYA 38-39 13. YAKSHAGANA 40 2 REVISED REFERENCE LIST FOR DANCE AS ON 28/02/2017 BHARATANATYAM OUTSTANDING 1. Ananda Shankar Jayant (Also Kuchipudi) (Up) 2007 2. Bali Vyjayantimala 3. Bhide Sucheta 4. Chandershekar C.V. 03.05.1998 5. Chandran Geeta (NCR) 28.10.1994 (Up) August 2005 6. Devi Rita 7. Dhananjayan V.P. & Shanta 8. Eshwar Jayalakshmi (Up) 28.10.1994 9. Govind (Gopalan) Priyadarshini 03.05.1998 10. Kamala (Migrated) 11. Krishnamurthy Yamini 12. Malini Hema 13. Mansingh Sonal (Also Odissi) 14. Narasimhachari & Vasanthalakshmi 03.05.1998 15. Narthaki Nataraj (Chennai) 2007 (Up)2017 16. Pratibha Prahlad (Approved by D.G March 2004) Bangaluru 17. Raghupathy Sudharani 18. Samson Leela 19. Sarabhai Mallika (Up) 28.10.1994 20. Saroja M K 21. Sarukkai Malavika 22. Sathyanarayanan Urmila (Chennai) 28.10.94 (Up)3.05.1998 23. Sehgal Kiran (Also Odissi) 24. -

2018 Shruti Amar 1311872 Et

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ Folklore, Myth, and Indian Fiction in English, 1930-1961 Amar, Shruti Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 28. Sep. 2021 Folklore, Myth, and Indian Fiction in English, 1930-1961 Shruti Amar Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy King’s College London 1 There is no village in India, however mean, that has not a rich sthala-purana, or legendary history of its own. -

Download Entire Journal Volume [PDF]

JOURNAL OF PUNJAB STUDIES Editors Indu Banga Panjab University, Chandigarh, INDIA Mark Juergensmeyer University of California, Santa Barbara, USA Gurinder Singh Mann University of California, Santa Barbara, USA Ian Talbot Southampton University, UK Shinder Singh Thandi Coventry University, UK Book Review Editor Eleanor Nesbitt University of Warwick, UK Ami P. Shah University of California, Santa Barbara, USA Editorial Advisors Ishtiaq Ahmed Stockholm University, SWEDEN Tony Ballantyne University of Otago, NEW ZEALAND Parminder Bhachu Clark University, USA Harvinder Singh Bhatti Punjabi University, Patiala, INDIA Anna B. Bigelow North Carolina State University, USA Richard M. Eaton University of Arizona, Tucson, USA Ainslie T. Embree Columbia University, USA Louis E. Fenech University of Northern Iowa, USA Rahuldeep Singh Gill California Lutheran University, Thousand Oaks, USA Sucha Singh Gill Punjabi University, Patiala, INDIA Tejwant Singh Gill Guru Nanak Dev University, Amritsar, INDIA David Gilmartin North Carolina State University, USA William J. Glover University of Michigan, USA J.S. Grewal Institute of Punjab Studies, Chandigarh, INDIA John S. Hawley Barnard College, Columbia University, USA Gurpreet Singh Lehal Punjabi University, Patiala, INDIA Iftikhar Malik Bath Spa University, UK Scott Marcus University of California, Santa Barbara, USA Daniel M. Michon Claremont McKenna College, CA, USA Farina Mir University of Michigan, USA Anne Murphy University of British Columbia, CANADA Kristina Myrvold Lund University, SWEDEN Rana Nayar -

Punjabi Language and Dialects VII Oral Literature VIII Folk Music and Dances , APPENDIX BIBLIOGRAPHY ? INDEX

FOLKLj THE SOHINDER SINGH BEDI «5t / J \ • ft i * i o / r<)f D */«. "W* *t **a *<#f <*a FOLKLORE OF THE PUNJAB \ i folklore of India FOLKLORE OF THE PUNJAB Sohinder SinghjBedi • National Book Trust, India \ V First Edition 1971 (Saka 1893) Second Reprint 1991 (Saka 1913) © Sohinder Singh Bedi, 1971 Rs. 23.00 Published by the Director, National Book Trust, India, A-5, Green Park, New Delhi-110016 f -*» CONTENTS LIST OP ILLUSTRATIONS ' Chapter I The Region and the People) i II Myth and Mythology III Magic and Religion IV Customs and Traditions , V Fairs and Festivals f VI Punjabi Language and Dialects VII Oral Literature VIII Folk Music and Dances , APPENDIX BIBLIOGRAPHY ? INDEX • / LI&T OF ILLUSTRATIONS A Rural Scene The Jewellery a Punjabi Girl is fond of A Nihang Singh in Traditional Costume I A Sister Tying Rakhi on the Wrist of Her Brother, A Holi Scene An Image of Sanjhi Devi • A Wandering Minstrel i A Giddha Dancer Close-up of a Bhangra Dancer ABhangra Dance A Piece of Folk-art A Scene from a Folk-dance Folk-artists at Work \ I r CHAPTER I THE ^REGION AND THE PEOPLE / "PUNJAB"—the land of five rivers—is proud of its ancient heritage. This is the cradle and breeding-place-of the Vedic culture of the Aryans. Rishis and munis composed the earliest hymns of the oldest book "in the world, the Rig Veda, on the banks of its rivers. Excavations of Harappa and Rupar reveal that even before the Aryans, a great civilization flourished here. -

Punjabis of Malaysia - Information Sheet

PHONE: 08 93901922 or 1800826413 WEB: www.goodrunsolutions.com.au E-MAIL: [email protected] The Bicultural Inclusion Support Services (BISS) Team at GoodRun Solutions has researched the information provided in this publication through the referenced sources. No responsibility is taken for the accuracy of the information supplied. www.goodrunsolutions.com.au 2009 PUNJABIS OF MALAYSIA - INFORMATION SHEET BACKGROUND Malaysia is divided into two geographical sections: Peninsular Malaysia and East Malaysia, which includes the provinces of Sabah and Sarawak in North Borneo. The two divisions are separated by the South China Sea. Peninsular Malaysia is bordered by Thailand and Singapore. Sabah and Sarawak are bordered by Kalimantan. An influx of Punjabis arrived in Malaysia as political prisoners in the nineteenth century. In 1947 the Punjab state was divided. At this time most of the Muslims fled to Pakistan and the Sikhs and Hindus remained in Punjab. A further division occurred in 1966 when the state was trifurcated. Some Punjabis would have fled to Malaysia after these political upheavals. There are approximately 90,000 Punjabis in Malaysia. LANGUAGE Even though there are some religious differences, the language, Punjabi, is common between them. Malaysian Punjabi families are likely to also speak Bahasa Malay, the official language of Malaysia. The written language of Sikhs is called Gurmukhi. The written language of Punjabi Hindus is Hindi. The written language of Muslim Sikhs might be either Punjabi or Urdu. RELIGION Originally from the Punjab area of North India and Pakistan, Punjabis come from three distinct religious groups: Sikh, Muslim and Hindu. Punjabi Sikhs believe in one god who cannot take human form.