The Wills Memorial Building Is an Icon of Bristol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The University of Bristol Historic Gardens 2Nd Edition Marion Mako

The University Bristol of Historic Gardens Marion Mako Marion UK £5 Marion Mako is a freelance historic garden and landscape historian. She has a Masters Degree in Garden History designed by greenhatdesign.co.uk ISBN 978-0-9561001-5-3 from the University of Bristol where she occasionally lectures. She researches public and private gardens, leads bespoke garden tours and offers illustrated talks. 2nd Edition The University of Bristol She has collaborated with Professor Tim Mowl on two 2nd Edition books in The Historic Gardens of England series: Cheshire Historic Gardens 9 780956 100153 and Somerset. Marion lives in Bristol. Marion Mako The University of Bristol Historic Gardens 2nd Edition Marion Mako Acknowledgements The history of these gardens is based on both primary and secondary research and I would like to acknowledge my gratitude to the authors of those texts who made their work available to me. In addition, many members of staff and students, both past and present, have shared their memories, knowledge and enthusiasm. In particular, I would like to thank Professor Timothy Mowl and Alan Stealey for their support throughout the project, and also the wardens of the University’s halls of residence, Dr. Martin Crossley-Evans, Professor Julian Rivers, Professor Gregor McLennan and Dr. Tom Richardson. For assistance with archival sources: Dr. Brian Pollard, Annie Burnside, Janice Butt, Debbie Hutchins, Alex Kolombus, Dr. Clare Hickman, Noni Bemrose, Rynholdt George, Will Costin, Anne de Verteuil, Douglas Gillis, Susan Darling, Stephanie Barnes, Cheryl Slater, Dr. Laura Mayer, Andy King, Judy Preston, Nicolette Smith and Peter Barnes. Staff at the following libraries and collections, have been most helpful: Bristol Reference Library, Bristol Record Office, The British Library, The British Museum, Bristol Museum and Art Gallery and especially Michael Richardson and the staff of Special Collections at the University of Bristol Arts and Social Sciences Library. -

Planning and Heritage Statement

PLANNING AND HERITAGE STATEMENT Installation and replacement of roof-level edge protection November 2020 The Fry Building Woodland Road Bristol BS8 1UG CSJ Reference JB.5738 www.csj-planning.co.uk | [email protected] CSJ Planning Consultants Ltd, 1 Host Street, Bristol, BS1 5BU Planning and Heritage Statement – Fry Building, Woodland Road, Bristol BS8 1UG CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 1 SUBMITTED DOCUMENTS AND PLANS 1 2. SITE DESCRIPTION 2 CONTEXT 2 SITE DESIGNATIONS 2 3. PLANNING HISTORY 4 4. PLANNING POLICY CONTEXT 6 LOCAL POLICY CONTEXT 6 SUPPLEMENTARY PLANNING DOCUMENTS 7 NATIONAL POLICY CONTEXT 7 HERITAGE LEGISLATION 7 HERITAGE POLICY GUIDANCE 7 5. THE PROPOSED DEVELOPMENT 9 6. KEY PLANNING CONSIDERATIONS 10 KEY PLANNING CONSIDERATION 1 – THE PRINCIPLE OF DEVELOPMENT 10 KEY PLANNING CONSIDERATION 2 – MEETING THE UNIVERSITY’S NEEDS 10 KEY PLANNING CONSIDERATION 3 – APPROPRIATE DESIGN 11 KEY PLANNING CONSIDERATION 4 – HERITAGE IMPACT 12 7. SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION 16 www.csj-planning.co.uk Planning and Heritage Statement – Fry Building, Woodland Road, Bristol BS8 1UG 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1. This Planning and Heritage Statement has been prepared by CSJ Planning on behalf of the applicant, the University of Bristol, for Planning and Listed Building Consent for the installation and replacement of roof-level edge protection / guardrailing at the Fry Building, Woodland Road. 1.2. The development is required as existing edge protection is either lacking or so substandard that it falls below the current safety requirements of Building Regulations and the University. Discussions regarding the proposed system have been undertaken with the University’s building maintenance staff to ensure the proposals meet their needs and requirements. -

University of Bristol Walk

Book of Walks @FestivalofIdeas New Edition 2017 www.ideasfestival.co.uk In partnership with: Walk 6: University of Bristol/ 10 6 9 5 8 7 4 3 2 1 of Architecture (1756). It was home to the nineteenth-century 'man-of- Walk 6: University of Bristol/ leters' John Addington Symonds and his daughter Katharine Furse, who became the first director of the Women's Royal Naval Service and the World Association of Girl Guides and Girl Scouts. This walk of around one-and-a-half miles provides a relatively level route from Clifon Village As you continue along Clifon Road, you will pass Richmond House, a c1701 Grade II-listed building with a Georgian frontage concealing student accommodation through to some of the its true origin. Recent works to remove unsecure render revealed the university’s academic buildings on the outskirts tall narrow windows and timber lintels of the original structure. Such changes to the façade of buildings are quite common in the city. Turn of Cotham. It starts and ends at sites associated right into York Place where you can see on your right the ornamental with the English (more accurately, British) Civil gardens that surround Manor House, which dates from c1730, and Manor Hall (2), our next stop. War, picking up on significant periods of human development and events along the way. Manor Hall was designed by George Oatley and opened in 1932 as a women’s hall of residence. Here you will see a magnificent horse chestnut isolated in its own island of retained ground next to steps that descend The Walk from York Place to the entrance to the hall. -

Mbchb Programme Newsletter 1 2018-19

MB ChB Newsletter - academic year 2018-19 No. 1 The end of term comes as a relief to us all, but Introduction especially for our final year students. They have At the start of this term the MB ChB applied for their first jobs and have just sat their administrative and leadership team moved into main written exams. Some of them have just had, smart new offices in 5 Tyndall Avenue. or are about to have, interviews for academic foundation programme posts. We wish them luck. __________________________ In this newsletter: • Staff Changes • Faculty Student Advice Service • Breaking news: new 45p mileage rate • Student Achievements • FoM Conference • INSPIRE Conference • Friday Night Feast with Jamie Oliver • Dates for your diary • Season’s greetings We are trying to make this building feel like more ____________________________________ of a home for students and staff. Next term the Galenicals committee will be able to use some of Staff Changes the rooms at evenings and weekends. New Deputy Programme Directors Our new MB ChB Blackboard site has been well received by students and staff alike. We are In September Dr Jane Sansom and Dr Jonathan trying to make this even better. Next term we Tyrrell-Price joined the senior management will add a new section listing all the local and team as Deputy Programme Directors. They are national prizes to which students can apply. Our working closely with our Programme Directors Dr students have always enjoyed great success in Andrew Blythe (MB16) and Professor John the past. Henderson and Deputy Programme Director Dr Eugene Lloyd (MB21) to ensure we continue to The MB21 curriculum is rolling out into year 2, deliver an outstanding programme. -

Postgraduate Prospectus Postgraduate Open Day

Postgraduate prospectus Postgraduate open day Wednesday 20 November 2019 Speak with academics, visit our campus and discover where your postgraduate journey could lead. bristol.ac.uk/postgrad-openday 2 3 Contents Welcome to Bristol Making an application ‘I chose Bristol because it is a Our University 4 Funding 36 Life in Bristol 6 How to apply 38 renowned university in a beautiful Fees 41 city! There are loads of things to Your postgraduate options Visit us 42 Taught programmes 12 do both on campus and in the area. Faculty of Arts 44 Postgraduate research 14 It is also known for great student Faculty of Engineering 46 Funded cohort-based doctoral training 16 Faculty of Health Sciences 48 support and an exciting array of World-class facilities 18 Faculty of Life Sciences 50 social activities and societies.’ Bristol Doctoral College 20 Faculty of Science 52 Cutting-edge research 22 Faculty of Social Sciences and Law 54 Miren (MA Comparative Literatures and Cultures) Global perspectives 24 Programmes A-Z 56-122 Student life Programme index 123 Bristol SU 26 Further information Take part 28 Campus map 126 Accommodation 30 Our location 128 Supporting you at university 32 Careers 34 @ChooseBristolPG Contacts Tel +44 (0)117 394 1649 bristoluniversity Email [email protected] UniversityofBristol For up-to-date information visit bristol.ac.uk/pg-study UniversityofBristol weibo.com/bristol bristol.ac.uk bristol.ac.uk WELCOME TO BRISTOL WELCOME TO BRISTOL 4 OUR UNIVERSITY OUR UNIVERSITY 5 Our university The University of Bristol is We attract students from all over the world, ‘A postgraduate degree from creating a rich and exciting international internationally renowned community. -

University College, Bristol 1876-1909

UNIVERSITY COLLEGE, BRISTOL 1876-1909 J. W. SHERBORNE ISSUED BY THE BRISTOL BRANCH OF THE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION THE UNIVERSITY, BRISTOL Price Fifty Pence 1 9 7 7 BRISTO� BRANCH OF THE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION UNIVERSITY COLLEGE, BRISTOL: 1876-1909 LOCAL HISTORY PAMPHLETS University College, Bristol opened its doors on the morning of Tuesday, 10 Oot10ber '1876 iand at 9.00 :a.m. Mr. W. R. Bousifielld- Hon. General Editor: PATRICK McGRATH a forgotten figure of the past - lectured on Mathematics. He was also responsible for Higher Mathematics at 10.00 a.m. Later there were lectures on Modern History and on Applied Mechanics (11.00 Assistant General Editor: PETER HARRIS a.m.) and on Modern Literature at 12.00 noon. In the afternoon Geology (2.00 p.m.) and Greek (3.00 p.m.) took their turn. This was, we may think, a versatile start on the first day of the new Univers,ity College, Bristol, 1876-1909 ,is ,rhe fortiiei�h pamphJlet · institution. Other lectures during the first week included Chemistry, to be published by the Bristol Branch of the Historical Association. Experimental Physics, French, Zoology, German, Latin, Chemistry It 1is based on ithe Frederick Creedh Jones Lec1ture whicih Mr. and Political Economy. In all during this term fourteen subjects Sherborne ideliivered in �he University of Bristiol in October 1976 were taught in day and in evening classes. It is clear that each as part of l�he cdeibr!attions to mark �he cenitenary, of the foundling member of staff moved swiftly into action and that the College orf Univeivs.ity Colilege, Brisitol. -

Tindall's Memories

MEMORIES OF THE PHYSICS DEPARTMENT K. F. Tindall 1 Memories of the Physics Department by K.F. Tindall Foreword My memories of life at the H.H.Wills Physics Laboratory in the University of Bristol span forty-one years. There are gaps, for I was not there for the whole of that period; indeed, in 1940, although I was in the building, I was there as an Admiralty visitor, and between 1949 and 1951 I was at St Mary's Hospital Medical School, Paddington. The urge to record some of the happenings in the department over the years has been with me for a long time. I promised myself I would do it when I retired but other interests affected my motivation. In December, 1989, I met Professor Thompson in the laboratory who asked me if I'd started writing. When I said I was thinking about it he encouraged me greatly, saying, "GET ON WITH IT!" I have tried to verify all facts and dates and am very grateful to all my colleagues throughout the University who have supplied information. From outside the department those whom I thank include Sir Alfred Pugsley, Mr.Evan Wright, Mrs.Molly Sanders, Chris Harries and Brian Jenkins. Don Carleton advised me to include everything I could remember. I have followed his advice but there are bound to be omissions. My thanks certainly go to Eleanor, my wife, who has not only tolerated my disappearing from the domestic scene for hours at a time while I applied fingers to keyboard, but has aided my memory and criticised, helpfully, my results. -

Royal Fort House Clifton Hill House Bristol Heart Institute (Open Between 10Am and 2Pm) Welcome Wills Memorial Building Queen’S Road, BS8 1RJ

Wills Memorial Building Address Doors Open Day at the University of Bristol Saturday 14 September 2013 A brief guide to the buildings open between 10am and 4pm Wills Memorial Building Theatre Collection Royal Fort House Clifton Hill House Bristol Heart Institute (open between 10am and 2pm) Welcome Wills Memorial Building Queen’s Road, BS8 1RJ We hope you enjoy visiting the buildings Guided tours There will be free tours to the top of the in this year’s programme: Tower. These must be booked on the day, on a first come, first served basis.† The Wills Memorial Building, Royal Fort House, Visit the Tower Tours reception desk on the Theatre Collection, Clifton Hill House and the ground floor to reserve a place. Tour times: 9.55am, 10.15am, the Bristol Heart Institute. 10.35am, 10.55am, 11.15am, 11.35am, 11.55am, 12.15pm, 12.35pm, 13.15pm, 13.35pm, The University of Bristol is pleased to This booklet gives you: 13.55pm, 14.15pm, 14.35pm, participate once more in Bristol Doors Times of free tours taking place at the 14.55pm, 15.15pm. Open Day 2013, a day when many of venues open today Tours also take place on the first Bristol’s significant contemporary and Short histories of the buildings Saturday and Wednesday of every month. historic buildings open their doors Notes on what to look out for while Information from Dave Skelhorne; to the general public. No advance you are visiting. tel: 0777 0265108 booking is required. email: [email protected] bristoldoorsopenday.org If you require additional support at any of The Entrance Hall, Reception Room and these events, such as wheelchair access or Library will all be open for free public The University is also hosting sign language interpretation, please contact viewing. -

The Richmond Building 105 Queens Road, Clifton, Bristol BS8 1LN Tel (0117) 331 8600

The Richmond Building 105 Queens Road, Clifton, Bristol BS8 1LN Tel (0117) 331 8600 www.bristolsu.org.uk Student Council Meeting 05/06/2017 Motion Name: Anti slavery commemoration Background: - Bristol’s callous and shameful tie’s to slavery is embedded around the city. Notorious for its prosperous slaving port and importing of goods from slave plantations, the wealth and profits from the trade is still prominent. - Many university associated buildings have links to slavery, including; Goldney Hall, Wills memorial building , Wills hall and an association to the Colston society. - University of Bristol’s black acceptance rate is 6.9 per cent making it the fifth lowest of any Russell Group university. Purpose: - Due to the University being located centrally in a city that profited greatly from slavery, it has a responsibility to address the history especially in university buildings that uphold those links. - With students attending halls such as Goldney and Wills we believe the university should play an active role in further educating the students on their links to slavery. - With a small percentage of BME students attending the university, we believe that addressing the history will further incite a more inclusive and diverse environment, especially due to the prospect of graduating in the Wills memorial building. - In the wake of several BME students being targeted and racially abused within the university grounds. Educating all students on the university buildings with links to slavery, essentially reduces ignorance and therefore indicates that the university is taking steps to provide are more inclusive environment for BME students. Action: - To have more information inside the Wills memorial building about its history and links to slave produced tobacco. -

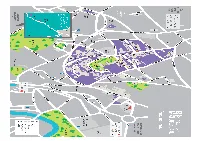

Map of University Precinct

Precinct map Key to University of Bristol building numbers Academic Registry, Senate House .............................................................................................................. 43 Mathematics, University Walk ..................................................................................................................... 29 Accommodation Office, The Hawthorns ...................................................................................................... 44 Mechanical Engineering, Queen's Building ................................................................................................ 20 Accounting and Finance, School of Economics, Finance and Management, 12 Priory Road ................... 68 Medical and Veterinary Sciences Faculty Office, Medical Sciences ......................................................... 16 Advanced Composites Centre for Innovation and Science (ACCIS), Queen's Building ............................ 20 Medical Education, Senate House .............................................................................................................. 43 Aerospace Engineering, Queen's Building .................................................................................................. 20 Medical Sciences Building, University Walk ............................................................................................... 16 ALSPAC - Children of the '90s, Oakfield House, Oakfield Grove ............................................................. 105 Medical Sciences Teaching -

Review of the Year 2012-2013 2 Welcome

Review of the year 2012-2013 2 Welcome It is always difficult to capture in such he higher education sector has recently gone through and is a publication the essence, energy and T likely to continue to experience turbulent times. It is how universities sheer excellence that underpins a deal with the challenges placed before university like Bristol – its leading-edge them that says something about their research, its highly talented and driven character and capabilities. Bristol is well placed to respond to the students and staff. This is no easy task various challenges and opportunities and I hope that we have managed to in equal measure and, as I hope you will see in this publication, is thriving convey perhaps a snapshot of what, against one of the most challenging in my view, makes Bristol such an backdrops this sector has known. exceptional university. Within this publication you will get a glimpse into the vast array of world- leading research carried out at Bristol. Our research activities cover a broad range of subject areas and our cross- disciplinary research is addressing some of the world’s most significant issues, while our interaction with business and other communities has significant impact on economies and people’s wellbeing. We also continue to innovate in the way that we educate our students so that they are best equipped to thrive in their chosen careers and, of course, we have exciting and significant estates developments to ensure that we provide the best research and educational environment for our academics and students. Welcome to the University of Bristol’s Annual Review. -

Estate Strategy 2013 - 2018

Estate Strategy 2013 - 2018 This strategy was completed and approved by the University’s Council on 23 November 2012. It was written by Patrick Finch, Sue Somerset and Martin Wiles, Bursar, Head of Space and Asset Management and Head of Sustainability at the University of Bristol. The contributions of many colleagues from within the Estates Office and the wider University community are gratefully acknowledged. 1 Introduction The University of Bristol Estate Strategy is one of a suite of corporate planning documents. It seeks to map University policy objectives onto the physical assets available and to ensure that the Estate, one of the University’s key resources alongside people and finance, is capable of supporting academic endeavour over the plan period. The Estate Strategy is designed to support the University’s corporate planning statements. Of particular relevance is the following extract from the University’s Vision document to 2016, relating to Estates Development; • Provide all parts of the University with flexible accommodation which is of a quality, size and functionality appropriate to the activities to be delivered and which supports the University’s vision. • Ensure the most efficient use of existing space and the development of capacity within the central Precinct area wherever appropriate • Continue to work to reduce carbon emissions and improve the sustainability of the physical estate • Provide residential accommodation which is attractive to students in form, service and location • Deliver an ambitious capital programme in support of the renewal of accommodation and the creation of adaptive capacity • Provide an attractive, safe, accessible and welcoming setting for University buildings that is sympathetic to the wider urban context In addition, the strategy addresses the University’s growth agenda established in 2011/12 and which requires a fresh look at the physical resources available.