University College, Bristol 1876-1909

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The University of Bristol Historic Gardens 2Nd Edition Marion Mako

The University Bristol of Historic Gardens Marion Mako Marion UK £5 Marion Mako is a freelance historic garden and landscape historian. She has a Masters Degree in Garden History designed by greenhatdesign.co.uk ISBN 978-0-9561001-5-3 from the University of Bristol where she occasionally lectures. She researches public and private gardens, leads bespoke garden tours and offers illustrated talks. 2nd Edition The University of Bristol She has collaborated with Professor Tim Mowl on two 2nd Edition books in The Historic Gardens of England series: Cheshire Historic Gardens 9 780956 100153 and Somerset. Marion lives in Bristol. Marion Mako The University of Bristol Historic Gardens 2nd Edition Marion Mako Acknowledgements The history of these gardens is based on both primary and secondary research and I would like to acknowledge my gratitude to the authors of those texts who made their work available to me. In addition, many members of staff and students, both past and present, have shared their memories, knowledge and enthusiasm. In particular, I would like to thank Professor Timothy Mowl and Alan Stealey for their support throughout the project, and also the wardens of the University’s halls of residence, Dr. Martin Crossley-Evans, Professor Julian Rivers, Professor Gregor McLennan and Dr. Tom Richardson. For assistance with archival sources: Dr. Brian Pollard, Annie Burnside, Janice Butt, Debbie Hutchins, Alex Kolombus, Dr. Clare Hickman, Noni Bemrose, Rynholdt George, Will Costin, Anne de Verteuil, Douglas Gillis, Susan Darling, Stephanie Barnes, Cheryl Slater, Dr. Laura Mayer, Andy King, Judy Preston, Nicolette Smith and Peter Barnes. Staff at the following libraries and collections, have been most helpful: Bristol Reference Library, Bristol Record Office, The British Library, The British Museum, Bristol Museum and Art Gallery and especially Michael Richardson and the staff of Special Collections at the University of Bristol Arts and Social Sciences Library. -

Planning and Heritage Statement

PLANNING AND HERITAGE STATEMENT Installation and replacement of roof-level edge protection November 2020 The Fry Building Woodland Road Bristol BS8 1UG CSJ Reference JB.5738 www.csj-planning.co.uk | [email protected] CSJ Planning Consultants Ltd, 1 Host Street, Bristol, BS1 5BU Planning and Heritage Statement – Fry Building, Woodland Road, Bristol BS8 1UG CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 1 SUBMITTED DOCUMENTS AND PLANS 1 2. SITE DESCRIPTION 2 CONTEXT 2 SITE DESIGNATIONS 2 3. PLANNING HISTORY 4 4. PLANNING POLICY CONTEXT 6 LOCAL POLICY CONTEXT 6 SUPPLEMENTARY PLANNING DOCUMENTS 7 NATIONAL POLICY CONTEXT 7 HERITAGE LEGISLATION 7 HERITAGE POLICY GUIDANCE 7 5. THE PROPOSED DEVELOPMENT 9 6. KEY PLANNING CONSIDERATIONS 10 KEY PLANNING CONSIDERATION 1 – THE PRINCIPLE OF DEVELOPMENT 10 KEY PLANNING CONSIDERATION 2 – MEETING THE UNIVERSITY’S NEEDS 10 KEY PLANNING CONSIDERATION 3 – APPROPRIATE DESIGN 11 KEY PLANNING CONSIDERATION 4 – HERITAGE IMPACT 12 7. SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION 16 www.csj-planning.co.uk Planning and Heritage Statement – Fry Building, Woodland Road, Bristol BS8 1UG 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1. This Planning and Heritage Statement has been prepared by CSJ Planning on behalf of the applicant, the University of Bristol, for Planning and Listed Building Consent for the installation and replacement of roof-level edge protection / guardrailing at the Fry Building, Woodland Road. 1.2. The development is required as existing edge protection is either lacking or so substandard that it falls below the current safety requirements of Building Regulations and the University. Discussions regarding the proposed system have been undertaken with the University’s building maintenance staff to ensure the proposals meet their needs and requirements. -

Heroic Chancellor: Winston Churchill and the University of Bristol 1929–65

Heroic Chancellor: Winston Churchill and the University of Bristol 1929–65 David Cannadine Heroic Chancellor: Winston Churchill and the University of Bristol 1929–65 To the Chancellors and Vice-Chancellors of the University of Bristol past, present and future Heroic Chancellor: Winston Churchill and the University of Bristol 1929–65 David Cannadine LONDON INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH Published by UNIVERSITY OF LONDON SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU © David Cannadine 2016 All rights reserved This text was first published by the University of Bristol in 2015. First published in print by the Institute of Historical Research in 2016. This PDF edition published in 2017. This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY- NCND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN 978 1 909646 18 6 (paperback edition) ISBN 978 1 909646 64 3 (PDF edition) I never had the advantage of a university education. Winston Churchill, speech on accepting an honorary degree at the University of Copenhagen, 10 October 1950 The privilege of a university education is a great one; the more widely it is extended the better for any country. Winston Churchill, Foundation Day Speech, University of London, 18 November 1948 I always enjoy coming to Bristol and performing my part in this ceremony, so dignified and so solemn, and yet so inspiring and reverent. Winston Churchill, Chancellor’s address, University of Bristol, 26 November 1954 Contents Preface ix List of abbreviations xi List of illustrations xiii Introduction 1 1. -

UNIVERSITY of LONDON, SCHOOL of ADVANCED STUDY Senate

Downloaded from the Humanities Digital Library http://www.humanities-digital-library.org Open Access books made available by the School of Advanced Study, University of London ***** Publication details: Heroic Chancellor: Winston Churchill and the University of Bristol 1929–65 David Cannadine http://humanities-digital-library.org/index.php/hdl/catalog/book/heroicchancellor DOI: 10.14296/517.9781909646643 ***** This edition published 2017 by UNIVERSITY OF LONDON SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH Senate House, Malet St, Bloomsbury, London WC1E 7HU, United Kingdom ISBN 978 1 909646 64 3 (PDF edition) This work is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. More information regarding CC licenses is available at https://creativecommons.org/licenses UNIVERSITY OF LONDON, SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY Senate House, Malet Street, London, WC1E 7HU Enquiries: [email protected] Heroic Chancellor: Winston Churchill and the University of Bristol 1929–65 David Cannadine Heroic Chancellor: Winston Churchill and the University of Bristol 1929–65 To the Chancellors and Vice-Chancellors of the University of Bristol past, present and future Heroic Chancellor: Winston Churchill and the University of Bristol 1929–65 David Cannadine LONDON INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH Published by UNIVERSITY OF LONDON SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU © David Cannadine 2016 All rights reserved This text was first published by the University of Bristol in 2015. First published in print by the Institute of Historical Research in 2016. This PDF edition published in 2017. This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY- NCND 4.0) license. -

University of Bristol Walk

Book of Walks @FestivalofIdeas New Edition 2017 www.ideasfestival.co.uk In partnership with: Walk 6: University of Bristol/ 10 6 9 5 8 7 4 3 2 1 of Architecture (1756). It was home to the nineteenth-century 'man-of- Walk 6: University of Bristol/ leters' John Addington Symonds and his daughter Katharine Furse, who became the first director of the Women's Royal Naval Service and the World Association of Girl Guides and Girl Scouts. This walk of around one-and-a-half miles provides a relatively level route from Clifon Village As you continue along Clifon Road, you will pass Richmond House, a c1701 Grade II-listed building with a Georgian frontage concealing student accommodation through to some of the its true origin. Recent works to remove unsecure render revealed the university’s academic buildings on the outskirts tall narrow windows and timber lintels of the original structure. Such changes to the façade of buildings are quite common in the city. Turn of Cotham. It starts and ends at sites associated right into York Place where you can see on your right the ornamental with the English (more accurately, British) Civil gardens that surround Manor House, which dates from c1730, and Manor Hall (2), our next stop. War, picking up on significant periods of human development and events along the way. Manor Hall was designed by George Oatley and opened in 1932 as a women’s hall of residence. Here you will see a magnificent horse chestnut isolated in its own island of retained ground next to steps that descend The Walk from York Place to the entrance to the hall. -

Tyndall's Memories 1958

Sixty years of Academic Life in Bristol A. M. Tyndall [The following talk was given to the Forum of the Senior Common Room of the University of Bristol on 10 March 1958 by the late A. M. Tyndall, who was at that time Professor Emeritus of Physics, having joined the staff in 1903, been Professor of Physics from 1919 to 1948, and acting Vice-Chancellor 1945—46. The text appeared, in slightly shortened form, in 'University and Community', edited by McQueen and Taylor, 1976: a collection of essays produced to mark the centenary of the founding of University College, Bristol. The Editors were then extremely grateful to Dr Anne Cole for providing a transcript of a tape-recording of the talk; and so are we.] I thought this was going to be a conversation piece to a small group of intimate friends! As I look at the audience, I realise that I joined the Staff of University College, Bristol at a time when few of the men and, of course, none of the women were born! 1 was a student before that and in fact it will be sixty years next October since I first entered the doors of University College with the intention of studying for a degree of the University of London in a scientific subject. I was one of about 220 students in the University College at that time, of whom 60 were in what was really an affiliated institution called the Day Training College for Women Teachers. The income of the College was then a little under £5,000 a year. -

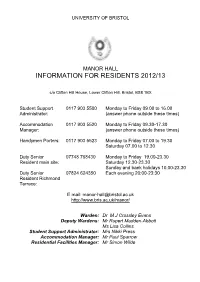

Manor Hall Residents' Handbook

UNIVERSITY OF BRISTOL MANOR HALL INFORMATION FOR RESIDENTS 2012/13 c/o Clifton Hill House, Lower Clifton Hill, Bristol, BS8 1BX Student Support 0117 903 5500 Monday to Friday 09.00 to 16.00 Administrator: (answer phone outside these times) Accommodation 0117 903 5520 Monday to Friday 09.30-17.30 Manager: (answer phone outside these times) Handymen Porters: 0117 903 5523 Monday to Friday 07.00 to 19.30 Saturday 07.00 to 12.30 Duty Senior 07748 768430 Monday to Friday 19.00-23.30 Resident main site: Saturday 12.30-23.30 Sunday and bank holidays 10.00-23.30 Duty Senior 07824 624350 Each evening 20:00-23:30 Resident Richmond Terrace: E mail: [email protected] http://www.bris.ac.uk/manor/ Warden: Dr M J Crossley Evans Deputy Wardens: Mr Rupert Madden-Abbott Ms Lisa Collins Student Support Administrator: Mrs Nikki Press Accommodation Manager: Mr Paul Sparrow Residential Facilities Manager: Mr Simon Wilde CONTENTS WARDEN’S WELCOME............................................. 5 INTRODUCTION .................................................. 6 Your Accommodation Contract ................................... 6 Arriving at Manor Hall.......................................... 7 Hall Location and Site Plan...................................... 7 What To Bring With You ........................................ 7 What Not To Bring With You..................................... 8 Accommodation Inventory ...................................... 8 GENERAL INFORMATION ABOUT MANOR HALL ......................... 9 Absence .................................................. -

Mbchb Programme Newsletter 1 2018-19

MB ChB Newsletter - academic year 2018-19 No. 1 The end of term comes as a relief to us all, but Introduction especially for our final year students. They have At the start of this term the MB ChB applied for their first jobs and have just sat their administrative and leadership team moved into main written exams. Some of them have just had, smart new offices in 5 Tyndall Avenue. or are about to have, interviews for academic foundation programme posts. We wish them luck. __________________________ In this newsletter: • Staff Changes • Faculty Student Advice Service • Breaking news: new 45p mileage rate • Student Achievements • FoM Conference • INSPIRE Conference • Friday Night Feast with Jamie Oliver • Dates for your diary • Season’s greetings We are trying to make this building feel like more ____________________________________ of a home for students and staff. Next term the Galenicals committee will be able to use some of Staff Changes the rooms at evenings and weekends. New Deputy Programme Directors Our new MB ChB Blackboard site has been well received by students and staff alike. We are In September Dr Jane Sansom and Dr Jonathan trying to make this even better. Next term we Tyrrell-Price joined the senior management will add a new section listing all the local and team as Deputy Programme Directors. They are national prizes to which students can apply. Our working closely with our Programme Directors Dr students have always enjoyed great success in Andrew Blythe (MB16) and Professor John the past. Henderson and Deputy Programme Director Dr Eugene Lloyd (MB21) to ensure we continue to The MB21 curriculum is rolling out into year 2, deliver an outstanding programme. -

Student Accommodation Topic Paper

Bristol Central Area Plan Publication Version (February 2014) Student Accommodation Topic Paper Student Accommodation – Issues and policy approach 1. Introduction 1.1. Bristol is host to two major higher education institutions, the University of Bristol (UoB), located within the city centre, and the University of the West of England (UWE), located to the north of the city and within the adjoining authority of South Gloucestershire. Each plays a significant role in the city’s economy, helping to maintain Bristol as a strong centre for research and innovation, supporting the city’s knowledge and technology industries and contributing to local business through student spend. Both Universities also make a significant contribution to the city’s social and cultural life. Their sizeable student communities add much to Bristol’s reputation as a vibrant and diverse city. Their strong academic standing and international connections also strengthen Bristol’s status as an important European centre. 1.2. Bristol’s future success is linked to the continued growth and development of these institutions, supported through a positive planning policy approach. With this come challenges; in particular, the management of rising student numbers and the adequate supply of good quality accommodation in appropriate locations. In recent years demand for student accommodation has placed pressure on the local housing stock often resulting in perceived or actual harmful impacts on communities accommodating students, especially in areas close to the UoB. With aspirations for increased growth the council has a clear and robust policy strategy that addresses such issues whilst also supporting the development plans of these important institutions. -

Postgraduate Prospectus Postgraduate Open Day

Postgraduate prospectus Postgraduate open day Wednesday 20 November 2019 Speak with academics, visit our campus and discover where your postgraduate journey could lead. bristol.ac.uk/postgrad-openday 2 3 Contents Welcome to Bristol Making an application ‘I chose Bristol because it is a Our University 4 Funding 36 Life in Bristol 6 How to apply 38 renowned university in a beautiful Fees 41 city! There are loads of things to Your postgraduate options Visit us 42 Taught programmes 12 do both on campus and in the area. Faculty of Arts 44 Postgraduate research 14 It is also known for great student Faculty of Engineering 46 Funded cohort-based doctoral training 16 Faculty of Health Sciences 48 support and an exciting array of World-class facilities 18 Faculty of Life Sciences 50 social activities and societies.’ Bristol Doctoral College 20 Faculty of Science 52 Cutting-edge research 22 Faculty of Social Sciences and Law 54 Miren (MA Comparative Literatures and Cultures) Global perspectives 24 Programmes A-Z 56-122 Student life Programme index 123 Bristol SU 26 Further information Take part 28 Campus map 126 Accommodation 30 Our location 128 Supporting you at university 32 Careers 34 @ChooseBristolPG Contacts Tel +44 (0)117 394 1649 bristoluniversity Email [email protected] UniversityofBristol For up-to-date information visit bristol.ac.uk/pg-study UniversityofBristol weibo.com/bristol bristol.ac.uk bristol.ac.uk WELCOME TO BRISTOL WELCOME TO BRISTOL 4 OUR UNIVERSITY OUR UNIVERSITY 5 Our university The University of Bristol is We attract students from all over the world, ‘A postgraduate degree from creating a rich and exciting international internationally renowned community. -

18Open Day 2018

Open day 2018 Programme Friday 15 June 18Saturday 16 June OPEN DAY 2018 OPEN DAY 2018 2 WELCOME WELCOME 3 Welcome Welcome Welcome to the University of Bristol. We Enjoy a taste of About your open day 4 have designed our open days so that they Bristol with street Exhibition 6 provide an enjoyable and comprehensive insight into student life at the University. I food and a place to Accommodation 8 encourage you to take advantage of the relax among the University campus map 10 full range of activities available. Our open greenery of Royal Information talks 12 days offer unique access to our beautiful Fort Gardens at Subject activities 13 campuses at Langford and Clifton, so please Veterinary subject explore and take opportunities to speak the centre of the activities 22 to staff about our innovative teaching and Clifton campus. Langford campus map 23 cutting-edge facilities at the subject displays and tours. The exhibition in the Richmond Building is an ideal opportunity to talk in person with our student services teams, who support every aspect of student life here. Finally, do take time to visit Royal Fort Gardens and experience a little of what our lively and independent city can offer. Professor Hugh Brady Vice-Chancellor and President Talk to teams from accommodation, admissions, funding and more at the open day exhibition. bristol.ac.uk/opendays bristol.ac.uk/opendays OPEN DAY 2018 OPEN DAY 2018 4 ABOUT YOUR OPEN DAY ABOUT YOUR OPEN DAY 5 About your open day Open days are special events, designed to help you explore subjects and student life at Bristol and experience a little of the unique atmosphere on campus. -

The Churchillian Autumn 2019

The Churchillian The Newsletter of the Churchill Hall Association Autumn 2019 Churchill Hall Association News Updates Would you like to help the Churchill Hall Association Committee? Churchill Hall Association (CHA) comprises all who have lived (and mostly loved their time) at Churchill Hall. The CHA Committee organises activities designed to support the Hall and to encourage engagement among all members of the CHA community The CHA Committee is looking for assistance and to diversify its membership. We would particularly welcome relatively recent Churchillians to help us to better represent the ideas of the entirety of the CHA community. Churchillians based in and around Bristol would also be very valuable. If you would like to join the CHA Committee, or discuss other volunteering opportunities, please contact us at [email protected] Alumni Reunion Weekend 2020 The 2020 Alumni Reunion Weekend will take place from Friday 17 – Sunday 19 July, and will include the annual CHA dinner on the Saturday evening (together with a wide variety of other events). More details will follow early next year, and be available on the website https://www.churchillhallassociation.co.uk/ or via newsletters and mailings from the University. At the CHA dinner, we will be welcoming a contingent from the Badock Hall Association, and a star Churchillian speaker – so don’t wait until you receive further information; make a diary note now (and then book as soon as you are able, once the details are known and a booking form is circulated) Visit to Chartwell (Kent) Following a successful day's visit to Chartwell- the long-time private home of Sir Winston Churchill- in 2014, we have been asked whether we would like another privately organised tour and lecture.