Tyndall's Memories 1958

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The University of Bristol Historic Gardens 2Nd Edition Marion Mako

The University Bristol of Historic Gardens Marion Mako Marion UK £5 Marion Mako is a freelance historic garden and landscape historian. She has a Masters Degree in Garden History designed by greenhatdesign.co.uk ISBN 978-0-9561001-5-3 from the University of Bristol where she occasionally lectures. She researches public and private gardens, leads bespoke garden tours and offers illustrated talks. 2nd Edition The University of Bristol She has collaborated with Professor Tim Mowl on two 2nd Edition books in The Historic Gardens of England series: Cheshire Historic Gardens 9 780956 100153 and Somerset. Marion lives in Bristol. Marion Mako The University of Bristol Historic Gardens 2nd Edition Marion Mako Acknowledgements The history of these gardens is based on both primary and secondary research and I would like to acknowledge my gratitude to the authors of those texts who made their work available to me. In addition, many members of staff and students, both past and present, have shared their memories, knowledge and enthusiasm. In particular, I would like to thank Professor Timothy Mowl and Alan Stealey for their support throughout the project, and also the wardens of the University’s halls of residence, Dr. Martin Crossley-Evans, Professor Julian Rivers, Professor Gregor McLennan and Dr. Tom Richardson. For assistance with archival sources: Dr. Brian Pollard, Annie Burnside, Janice Butt, Debbie Hutchins, Alex Kolombus, Dr. Clare Hickman, Noni Bemrose, Rynholdt George, Will Costin, Anne de Verteuil, Douglas Gillis, Susan Darling, Stephanie Barnes, Cheryl Slater, Dr. Laura Mayer, Andy King, Judy Preston, Nicolette Smith and Peter Barnes. Staff at the following libraries and collections, have been most helpful: Bristol Reference Library, Bristol Record Office, The British Library, The British Museum, Bristol Museum and Art Gallery and especially Michael Richardson and the staff of Special Collections at the University of Bristol Arts and Social Sciences Library. -

Heroic Chancellor: Winston Churchill and the University of Bristol 1929–65

Heroic Chancellor: Winston Churchill and the University of Bristol 1929–65 David Cannadine Heroic Chancellor: Winston Churchill and the University of Bristol 1929–65 To the Chancellors and Vice-Chancellors of the University of Bristol past, present and future Heroic Chancellor: Winston Churchill and the University of Bristol 1929–65 David Cannadine LONDON INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH Published by UNIVERSITY OF LONDON SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU © David Cannadine 2016 All rights reserved This text was first published by the University of Bristol in 2015. First published in print by the Institute of Historical Research in 2016. This PDF edition published in 2017. This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY- NCND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN 978 1 909646 18 6 (paperback edition) ISBN 978 1 909646 64 3 (PDF edition) I never had the advantage of a university education. Winston Churchill, speech on accepting an honorary degree at the University of Copenhagen, 10 October 1950 The privilege of a university education is a great one; the more widely it is extended the better for any country. Winston Churchill, Foundation Day Speech, University of London, 18 November 1948 I always enjoy coming to Bristol and performing my part in this ceremony, so dignified and so solemn, and yet so inspiring and reverent. Winston Churchill, Chancellor’s address, University of Bristol, 26 November 1954 Contents Preface ix List of abbreviations xi List of illustrations xiii Introduction 1 1. -

Bristol City Council Development Management

Item no. Extension: Revised 4 February 2021 expiry date ‘Hold Date’ Bristol City Council Development Management Delegated Report and Decision Application No: 20/05736/F Registered: 7 December 2020 Type of Application: Full Planning Case Officer: Amy Prendergast Expiry Date: 1 February 2021 Site Address: Description of Development: Fry Building Installation and replacement of roof-level edge protection. University Of Bristol Woodland Road Bristol BS8 1UG Ward: Central Site Visit Date: Date Photos Taken: Consultation Expiry Dates: Advert 27 Jan 2021 Neighbour: and/or Site 27 Jan 2021 Notice: SITE DESCRIPTION This application relates to the roof of the Grade II Listed Frys building. Frys building is part of a group of Bristol University campus buildings and located east of Woodland Road within the Tyndall's Park Conservation Area. The building lies within the setting of a number of other listed buildings, including Wills Memorial Building (Grade II*), Browns Restaurant (Grade II) and 66 Queens Road (Grade II) Royal Fort House (Grade I), and the Physics Building (Grade II). HISTORY The site has a long planning history. Of relevance, this application is being assessed alongside: 20/05737/LA Installation and replacement of roof-level edge protection. Date Closed PCO 3-Feb-21 Page 1 of 6 Item no. DEVELOPMENT CONTROL () DELEGATED Fry Building University Of Bristol Woodland Road Bristol BS8 1UG Other recent applications at the same address include: 20/05734/F Replacement of curtain walling surrounding a lift overrun and associated works. Date Closed 20/05735/LA Replacement of curtain walling surrounding a lift overrun and associated works. Date Closed APPLICATION The proposed development seeks new and replacement black painted guardrails at 1.1 metres high fixed to the inner side of the crenelated parapet. -

UNIVERSITY of LONDON, SCHOOL of ADVANCED STUDY Senate

Downloaded from the Humanities Digital Library http://www.humanities-digital-library.org Open Access books made available by the School of Advanced Study, University of London ***** Publication details: Heroic Chancellor: Winston Churchill and the University of Bristol 1929–65 David Cannadine http://humanities-digital-library.org/index.php/hdl/catalog/book/heroicchancellor DOI: 10.14296/517.9781909646643 ***** This edition published 2017 by UNIVERSITY OF LONDON SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH Senate House, Malet St, Bloomsbury, London WC1E 7HU, United Kingdom ISBN 978 1 909646 64 3 (PDF edition) This work is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. More information regarding CC licenses is available at https://creativecommons.org/licenses UNIVERSITY OF LONDON, SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY Senate House, Malet Street, London, WC1E 7HU Enquiries: [email protected] Heroic Chancellor: Winston Churchill and the University of Bristol 1929–65 David Cannadine Heroic Chancellor: Winston Churchill and the University of Bristol 1929–65 To the Chancellors and Vice-Chancellors of the University of Bristol past, present and future Heroic Chancellor: Winston Churchill and the University of Bristol 1929–65 David Cannadine LONDON INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH Published by UNIVERSITY OF LONDON SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU © David Cannadine 2016 All rights reserved This text was first published by the University of Bristol in 2015. First published in print by the Institute of Historical Research in 2016. This PDF edition published in 2017. This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY- NCND 4.0) license. -

Manor Hall Residents' Handbook

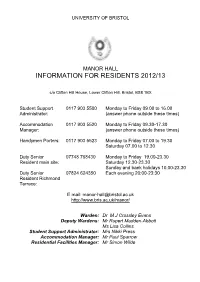

UNIVERSITY OF BRISTOL MANOR HALL INFORMATION FOR RESIDENTS 2012/13 c/o Clifton Hill House, Lower Clifton Hill, Bristol, BS8 1BX Student Support 0117 903 5500 Monday to Friday 09.00 to 16.00 Administrator: (answer phone outside these times) Accommodation 0117 903 5520 Monday to Friday 09.30-17.30 Manager: (answer phone outside these times) Handymen Porters: 0117 903 5523 Monday to Friday 07.00 to 19.30 Saturday 07.00 to 12.30 Duty Senior 07748 768430 Monday to Friday 19.00-23.30 Resident main site: Saturday 12.30-23.30 Sunday and bank holidays 10.00-23.30 Duty Senior 07824 624350 Each evening 20:00-23:30 Resident Richmond Terrace: E mail: [email protected] http://www.bris.ac.uk/manor/ Warden: Dr M J Crossley Evans Deputy Wardens: Mr Rupert Madden-Abbott Ms Lisa Collins Student Support Administrator: Mrs Nikki Press Accommodation Manager: Mr Paul Sparrow Residential Facilities Manager: Mr Simon Wilde CONTENTS WARDEN’S WELCOME............................................. 5 INTRODUCTION .................................................. 6 Your Accommodation Contract ................................... 6 Arriving at Manor Hall.......................................... 7 Hall Location and Site Plan...................................... 7 What To Bring With You ........................................ 7 What Not To Bring With You..................................... 8 Accommodation Inventory ...................................... 8 GENERAL INFORMATION ABOUT MANOR HALL ......................... 9 Absence .................................................. -

Student Accommodation Topic Paper

Bristol Central Area Plan Publication Version (February 2014) Student Accommodation Topic Paper Student Accommodation – Issues and policy approach 1. Introduction 1.1. Bristol is host to two major higher education institutions, the University of Bristol (UoB), located within the city centre, and the University of the West of England (UWE), located to the north of the city and within the adjoining authority of South Gloucestershire. Each plays a significant role in the city’s economy, helping to maintain Bristol as a strong centre for research and innovation, supporting the city’s knowledge and technology industries and contributing to local business through student spend. Both Universities also make a significant contribution to the city’s social and cultural life. Their sizeable student communities add much to Bristol’s reputation as a vibrant and diverse city. Their strong academic standing and international connections also strengthen Bristol’s status as an important European centre. 1.2. Bristol’s future success is linked to the continued growth and development of these institutions, supported through a positive planning policy approach. With this come challenges; in particular, the management of rising student numbers and the adequate supply of good quality accommodation in appropriate locations. In recent years demand for student accommodation has placed pressure on the local housing stock often resulting in perceived or actual harmful impacts on communities accommodating students, especially in areas close to the UoB. With aspirations for increased growth the council has a clear and robust policy strategy that addresses such issues whilst also supporting the development plans of these important institutions. -

18Open Day 2018

Open day 2018 Programme Friday 15 June 18Saturday 16 June OPEN DAY 2018 OPEN DAY 2018 2 WELCOME WELCOME 3 Welcome Welcome Welcome to the University of Bristol. We Enjoy a taste of About your open day 4 have designed our open days so that they Bristol with street Exhibition 6 provide an enjoyable and comprehensive insight into student life at the University. I food and a place to Accommodation 8 encourage you to take advantage of the relax among the University campus map 10 full range of activities available. Our open greenery of Royal Information talks 12 days offer unique access to our beautiful Fort Gardens at Subject activities 13 campuses at Langford and Clifton, so please Veterinary subject explore and take opportunities to speak the centre of the activities 22 to staff about our innovative teaching and Clifton campus. Langford campus map 23 cutting-edge facilities at the subject displays and tours. The exhibition in the Richmond Building is an ideal opportunity to talk in person with our student services teams, who support every aspect of student life here. Finally, do take time to visit Royal Fort Gardens and experience a little of what our lively and independent city can offer. Professor Hugh Brady Vice-Chancellor and President Talk to teams from accommodation, admissions, funding and more at the open day exhibition. bristol.ac.uk/opendays bristol.ac.uk/opendays OPEN DAY 2018 OPEN DAY 2018 4 ABOUT YOUR OPEN DAY ABOUT YOUR OPEN DAY 5 About your open day Open days are special events, designed to help you explore subjects and student life at Bristol and experience a little of the unique atmosphere on campus. -

The Churchillian Autumn 2019

The Churchillian The Newsletter of the Churchill Hall Association Autumn 2019 Churchill Hall Association News Updates Would you like to help the Churchill Hall Association Committee? Churchill Hall Association (CHA) comprises all who have lived (and mostly loved their time) at Churchill Hall. The CHA Committee organises activities designed to support the Hall and to encourage engagement among all members of the CHA community The CHA Committee is looking for assistance and to diversify its membership. We would particularly welcome relatively recent Churchillians to help us to better represent the ideas of the entirety of the CHA community. Churchillians based in and around Bristol would also be very valuable. If you would like to join the CHA Committee, or discuss other volunteering opportunities, please contact us at [email protected] Alumni Reunion Weekend 2020 The 2020 Alumni Reunion Weekend will take place from Friday 17 – Sunday 19 July, and will include the annual CHA dinner on the Saturday evening (together with a wide variety of other events). More details will follow early next year, and be available on the website https://www.churchillhallassociation.co.uk/ or via newsletters and mailings from the University. At the CHA dinner, we will be welcoming a contingent from the Badock Hall Association, and a star Churchillian speaker – so don’t wait until you receive further information; make a diary note now (and then book as soon as you are able, once the details are known and a booking form is circulated) Visit to Chartwell (Kent) Following a successful day's visit to Chartwell- the long-time private home of Sir Winston Churchill- in 2014, we have been asked whether we would like another privately organised tour and lecture. -

Bristol Big Give Wrap up Report 2014

Bristol Big Give Wrap Up Report 2014 September 2014 – August 2015 2 Contents Overview............................................................................................................................................... 5 Donations Results ............................................................................................................................... 6 British Heart Foundation – City .................................................................................................. 6 British Heart Foundation – UWE ............................................................................................... 6 British Heart Foundation - Unite................................................................................................ 6 University of Bristol Halls of Residence .................................................................................... 7 Evaluation by Key Partners .............................................................................................................. 8 British Heart Foundation .............................................................................................................. 8 The Community ............................................................................................................................ 8 Unite ............................................................................................................................................... 9 University of Bristol ...................................................................................................................... -

University College, Bristol 1876-1909

UNIVERSITY COLLEGE, BRISTOL 1876-1909 J. W. SHERBORNE ISSUED BY THE BRISTOL BRANCH OF THE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION THE UNIVERSITY, BRISTOL Price Fifty Pence 1 9 7 7 BRISTO� BRANCH OF THE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION UNIVERSITY COLLEGE, BRISTOL: 1876-1909 LOCAL HISTORY PAMPHLETS University College, Bristol opened its doors on the morning of Tuesday, 10 Oot10ber '1876 iand at 9.00 :a.m. Mr. W. R. Bousifielld- Hon. General Editor: PATRICK McGRATH a forgotten figure of the past - lectured on Mathematics. He was also responsible for Higher Mathematics at 10.00 a.m. Later there were lectures on Modern History and on Applied Mechanics (11.00 Assistant General Editor: PETER HARRIS a.m.) and on Modern Literature at 12.00 noon. In the afternoon Geology (2.00 p.m.) and Greek (3.00 p.m.) took their turn. This was, we may think, a versatile start on the first day of the new Univers,ity College, Bristol, 1876-1909 ,is ,rhe fortiiei�h pamphJlet · institution. Other lectures during the first week included Chemistry, to be published by the Bristol Branch of the Historical Association. Experimental Physics, French, Zoology, German, Latin, Chemistry It 1is based on ithe Frederick Creedh Jones Lec1ture whicih Mr. and Political Economy. In all during this term fourteen subjects Sherborne ideliivered in �he University of Bristiol in October 1976 were taught in day and in evening classes. It is clear that each as part of l�he cdeibr!attions to mark �he cenitenary, of the foundling member of staff moved swiftly into action and that the College orf Univeivs.ity Colilege, Brisitol. -

Bristol & Gloucestershire Archaeological Society

Bristol & Gloucestershire Archaeological Society Forthcoming M.J. Crossley Evans and Andrew Sulston, A History of Wills Hall, University of Bristol (2nd edition) (University of Bristol, Wills Hall Association 2017). 112pp.,104 pl., Hardback, £12.00. This is the 2nd edition of a history which has its origins in an exhibition of 1989: the 60th anniversary of the founding of Wills Hall. The subject is the first purpose-built hall of residence at the University of Bristol, itself a foundation of 1909, incorporating the earlier University College, Bristol, of 1876. In contrast with the later halls, Wills was designed on similar principles to that of an Oxbridge college. It is quadrangular, with the central court based upon the dimensions of those that the University Vice-Chancellor (Dr Thomas Loveday) himself measured in Oxford, and has rooms off staircases (rather than corridors) again in the Oxbridge fashion. Sir George Oatley of the Bristol firm Oatley & Lawrence was its architect, and he gave it a Cotswold style, with gables and mullioned windows. Unlike the later additions, this first phase was of stone. Its site was part of the former Stoke House Estate at Stoke Bishop, some 1¼ miles north of the university centre in University Road. Initially it was exclusively a male hall, deliberately well away from women’s accommodation at Clifton Hill House and (after 1932) that at Manor Hall. At George Wills’ insistence, it incorporated a Tudor-Gothic villa (Downside) of c.1830, built for Alfred George of the Bristol brewing family. The whole site had been purchased for the university by Henry Wills in 1922. -

Royal Fort House Clifton Hill House Bristol Heart Institute (Open Between 10Am and 2Pm) Welcome Wills Memorial Building Queen’S Road, BS8 1RJ

Wills Memorial Building Address Doors Open Day at the University of Bristol Saturday 14 September 2013 A brief guide to the buildings open between 10am and 4pm Wills Memorial Building Theatre Collection Royal Fort House Clifton Hill House Bristol Heart Institute (open between 10am and 2pm) Welcome Wills Memorial Building Queen’s Road, BS8 1RJ We hope you enjoy visiting the buildings Guided tours There will be free tours to the top of the in this year’s programme: Tower. These must be booked on the day, on a first come, first served basis.† The Wills Memorial Building, Royal Fort House, Visit the Tower Tours reception desk on the Theatre Collection, Clifton Hill House and the ground floor to reserve a place. Tour times: 9.55am, 10.15am, the Bristol Heart Institute. 10.35am, 10.55am, 11.15am, 11.35am, 11.55am, 12.15pm, 12.35pm, 13.15pm, 13.35pm, The University of Bristol is pleased to This booklet gives you: 13.55pm, 14.15pm, 14.35pm, participate once more in Bristol Doors Times of free tours taking place at the 14.55pm, 15.15pm. Open Day 2013, a day when many of venues open today Tours also take place on the first Bristol’s significant contemporary and Short histories of the buildings Saturday and Wednesday of every month. historic buildings open their doors Notes on what to look out for while Information from Dave Skelhorne; to the general public. No advance you are visiting. tel: 0777 0265108 booking is required. email: [email protected] bristoldoorsopenday.org If you require additional support at any of The Entrance Hall, Reception Room and these events, such as wheelchair access or Library will all be open for free public The University is also hosting sign language interpretation, please contact viewing.