FULL ISSUE (48 Pp., 2.2 MB PDF)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Case Study of Jining Religions in the Late Imperial and Republican Periods

www.ccsenet.org/ach Asian Culture and History Vol. 4, No. 2; July 2012 Pluralism, Vitality, and Transformability: A Case Study of Jining Religions in the Late Imperial and Republican Periods Jinghao Sun1 1 History Department, East China Normal University, Shanghai, China Correspondence: Jinghao Sun, History Department, East China Normal University, Shanghai 200241, China. Tel: 86-150-2100-6037. E-mail: [email protected] Received: March 12, 2012 Accepted: June 4, 2012 Online Published: July 1, 2012 doi:10.5539/ach.v4n2p16 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ach.v4n2p16 The final completion and publication of this article was supported by the New Century Program to Promote Excellent University Talents (no.: NECJ-10-0355). Abstract This article depicts the dynamic demonstrations of religions in late imperial and republican Jining. It argues with evidences that the open, tolerant and advanced urban circumstances and atmosphere nurtured the diversity and prosperity of formal religions in Jining in much of the Ming and Qing periods. It also argues that the same air and ethos enabled Jining to less difficultly adapt to the West-led modern epoch, with a notable result of welcoming Christianity, quite exceptional in hinterland China. Keywords: Jining, religions, urban, Grand Canal, hinterland, Christianity I. Introduction: A Special Case beyond Conventional Scholarly Images It seems a commonplace that intellectual and religious beliefs and practices in imperial Chinese inlands were conservative, which encouraged orthodoxy ideology or otherwise turned to heretic sectarianism. It is also commonplace that in the post-Opium War modern era, hinterland China, while being sluggishly appropriated into Westernized modernization, persistently resisted the penetration of Western values and institutes including Christianity. -

CURRICULUM VITAE Morton Falk Goldberg, MD, FACS, FAOSFRACO

CURRICULUM VITAE Morton Falk Goldberg, M.D., F.A.C.S., F.A.O.S. F.R.A.C.O. (Hon), M.D. (Hon., University Coimbra) PERSONAL DATA: Born, June 8, 1937 Lawrence, MA, USA Married, Myrna Davidov 5/6/1968 Children: Matthew Falk Michael Falk EDUCATION: A.B., Biology – Magna cum laude, 1958 Harvard College, Cambridge MA Detur Prize, 1954-1955 Phi Beta Kappa, Senior Sixteen 1958 M.D., Medicine – Cum Laude 1962 Lehman Fellowship 1958-1962 Alpha Omega Alpha, Senior Ten 1962 INTERNSHIP: Department of Medicine, 1962-1963 Peter Bent Brigham Hospital, Boston, MA RESIDENCY: Assistant Resident in Ophthalmology 1963-1966 Wilmer Ophthalmological Institute, Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, MD CHIEF RESIDENT: Chief Resident in Ophthalmology Mar. 1966-Jun. 1966 Yale-New Haven Hospital Chief Resident in Ophthalmology, Jul. 1966-Jun. 1967 Wilmer Ophthalmological Institute Johns Hopkins Hospital BOARD CERTIFICATION: American Board of Ophthalmology 1968 Page 1 CURRICULUM VITAE Morton Falk Goldberg, M.D., F.A.C.S., F.A.O.S. F.R.A.C.O. (Hon), M.D. (Hon., University Coimbra) HONORARY DEGREES: F.R.A.C.O., Honorary Fellow of the Royal Australian 1962 College of Ophthalmology Doctoris Honoris Causa, University of Coimbra, 1995 Portugal MEDALS: Inaugural Ida Mann Medal, Oxford University 1980 Arnall Patz Medal, Macula Society 1999 Prof. Isaac Michaelson Medal, Israel Academy Of 2000 Sciences and Humanities and the Hebrew University- Hadassah Medical Organization David Paton Medal, Cullen Eye Institute and Baylor 2002 College of Medicine Lucien Howe Medal, American Ophthalmological -

David Paton: Christian Mission Encounters Communism in China

CHAPTER NINE DAVID PATON: CHRISTIAN MISSION ENCOUNTERS COMMUNISM IN CHINA While serving as a visiting fellow of Cambridge University, England in the fall of 2005, I was asked to lead a discussion group with Master of Philosophy students on Christianity in China for the Divinity Faculty. Amongst the reading references, I found David Paton’s book, Christian Mission and the Judgment of God.1 David Paton had been a CMS mis- sionary in China for 10 years and was expelled from China in 1951. So he had experienced the end of the missionary era in China in the early 1950s. The book was first published in 1953 and was reprinted by Wm B. Eerdmans Co. in October 1996 (after Paton’s death in 1992), with the addition of an introduction by Rev. Bob Whyte and a foreword by Bishop K.H. Ting. They both endorsed Paton’s view from the experiences of Chinese Churches in the past forty years. Bob Whyte reported that many of Paton’s reflections remained of immedi- ate relevance today and the issues he had perceived as important in 1953 were still central to any reflections on the future of Christianity in China. Bishop Ting also confirmed that this book was a book of pro- phetic vision and Paton was a gift from God to the worldwide church. Dr. Gerald H. Anderson, the Emeritus Director of Overseas Ministries Study Center at New Haven (USA) added a remark on the cover- page, saying: “To have this classic available again is timely—even bet- ter with the new foreword by Bishop K.H. -

Washington State University Ninety-Second Annual Commencement

WASHINGTON STATE UNIVERSITY NINETY-SECOND ANNUAL COMMENCEMENT May 7, 1988 Appc,JrJncc of :,1 narnc on thh progr;.un i,r,; prcs"i.11nptivc evidence (Jf gr:,~du;,1tiun ancl gr:,ldu.:r.Hion houors .. bur if n1usr. no!. in ;u1y sense he n-·g~1rdcd :.i.s conclusive. Tl1c dip(oni;i {){" 1"l'lc un..i1 1 (::r:-iiry) !•;.igni:·d ;ind ~1c11Jc(] by ii:; proper i..>\\iccrs, reiT\~-lin,•~ ihc ()('fici;l.l tc·stirnuny of i 1·1e 1·ios-1;css!on of rh,-· c!cgrcc The Commencement Procession Order of Exercises Presiding-Dr. Samuel Smith, President Processional Candidates for Advanced Degrees Washington State University Wind Symphony Professor L. Keating Johnson, Conductor University Faculty Posting of the Colors Regents of the University Army ROTC Color Guard The National Anthem Honored Guests of the University Washington State University Wind Symphony Dr. Jane Wyss, Song Leader President of the University Invocation Reverend Graham Owen Hutchins Simpson United Methodist Church Introduction of Commencement Speaker Dr. Samuel Smith Commencement Address The Honorable Thomas S. Foley President's Faculty Excellence Awards Dr. Albert C. Yates Executive Vice President and Provost Instruction: Gerald L. Young Research: Linda L. Randall Public Service: Thomas L. Barton Festival March by Giacomo Puccini Washington State University Wind Symphony Bachelors Degrees Advanced Degrees Alma Mater The Assembly SPECIAL NOTE FOR PARENTS AND FRIENDS: Professional Recessional photographers will photograph all candidates as they receive their diploma covers from the deans at the all-university and Washington State University Wind Symphony college commencement ceremonies. A photo will be mailed to each graduate, and additional photos may be purchased at reasonable rates. -

Art S.5 Holiday Work Project Work

ART S.5 HOLIDAY WORK PROJECT WORK Make a study of the landscape around your home. S5 CRE 3 HW DR. JOHANN LUDWIG KRAPF Johann Ludwig Krapf (1810 - 1881) was a German missionary in East Africa, as well as an explorer, linguist, and traveler. Krapf played an important role in exploring East Africa with Johannes Rebmann. They were the first Europeans to see Mount Kenya and Kilimanjaro. Krapf also played a key role in exploring the East African coastline. EARLY LIFE Krapf was born into a Lutheran family of farmers in southwest Germany. From his school days onward he developed his gift for languages. He initially studied Latin, Greek, French and Italian. More languages were to follow throughout his life. After finishing school he joined the Base! Mission Seminary at age 17 but discontinued his studies as he had doubts about his missionary vocation. He read theology and graduated in 1834. While working as an assistant village pastor, he met a Basel missionary who encouraged him to resume his missionary vocation. In 1836 he was invited by the Anglican Church Missionary Society (CMS) to join their work in Ethiopia. Basel Mission seconded him to the Anglicans and from 1837- 1842 he worked in this ancient Christian land. Krapf later left Ethiopia and centered his interest on the Oromo - the Galla, people of southern Ethiopia who then were largely traditional believers. He learned their language and started translating parts of the New Testament into it. While 1842 saw Krapf receive a doctorate from Tubingen University for his research into the Ethiopian languages, it also witnessed the expulsion of all Western missionaries from Ethiopia, which ended his work there. -

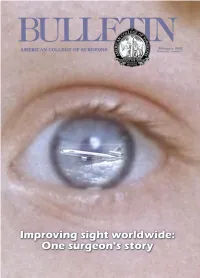

Bulletin February 2002

February 2002 Volume 87, Number 2 _________________________________________________________________ FEATURES Stephen J. Regnier Editor Surgeon takes flight to deliver improved sight worldwide 12 Walter J. Kahn, MD, FACS Linn Meyer Director of Communications Surgeons pocket PDAs to end paper chase: Part II 17 Karen Sandrick Diane S. Schneidman Senior Editor Liability premium increases may offer Tina Woelke opportunities for change 22 Graphic Design Specialist Christian Shalgian Alden H. Harken, Governors’ committee deals with range of risks 25 MD, FACS Donald E. Fry, MD, FACS Charles D. Mabry, MD, FACS Jack W. McAninch, A summary of the Ethics and Philosophy Lecture: Surgery—Is it an impairing profession? 29 MD, FACS Editorial Advisors Statement on bicycle safety and Tina Woelke the promotion of bicycle helmet use 30 Front cover design Tina Woelke Back cover design DEPARTMENTS About the cover... From my perspective Editorial by Thomas R. Russell, MD, FACS, ACS Executive Director 3 For the last 20 years, ORBIS, a not-for-profit orga- nization based in New York, FYI: STAT 5 NY, has been flying ophthal- mologists to developing lands Dateline: Washington 6 to treat blind and nearly Division of Advocacy and Health Policy blind patients and to train surgeons and other health care professionals in the pro- What surgeons should know about... 8 vision of advanced oph- OSHA regulation of blood-borne pathogens thalmic services. In “Sur- Adrienne Roberts geon takes flight to deliver improved sight worldwide,” p. 12, Walter J. Kahn, MD, Keeping current 32 FACS, discusses his experi- What’s new in ACS Surgery: Principles and Practice ences as a volunteer for Erin Michael Kelly ORBIS. -

Calvin Wilson Mateer, Forty-Five Years a Missionary In

Calvin Wilson <A Bio seraph if DANIEL W. HER ^ . 2-. / . 5 O / J tilt aiitoiojif/ii J, PRINCETON, N. J. //^ Purchased by the Hamill Missionary Fund. nv„ BV 3427 .M3 F5 Fisher, Daniel Webster, 183( -1913. Calvin Wilson Mateer CALVIN WILSON MATEER C. W. MATEER • »r \> JAN 301913 y ^Wmhi %^ Calvin Wilson Mateer FORTY-FIVE YEARS A MISSIONARY IN SHANTUNG, CHINA A BIOGRAPHY BY DANIEL W. FISHER PHILADELPHIA THE WESTMINSTER PRESS 1911 Copyright, 191 i, by The Trustees of the Presbyterian Board of Publication and Sabbath School Work Published September, 191 i AA CONTENTS Introduction 9 CHAPTER I The Old Home ^S ^ Birth—The Cumberland Valley—Parentage—Broth- Grandfather—Re- ers and Sisters, Father, Mother, In the moval to the "Hermitage"—Life on the Farm— Home—Stories of Childhood and Youth. CHAPTER II The Making of the Man 27 Native Endowments—Influence of the Old Home— Schoolmaster—Hunterstown Academy- \j Country Teaching School—Dunlap's Creek Academy—Pro- Recollections fession of Rehgion—Jefferson College— of 1857— of a Classmate—The Faculty—The Class '^ Semi-Centennial Letter. CHAPTER III Finding His Life Work 40 Mother and Foreign Missions—Beaver Academy- Theological Decision to be a Minister—Western Seminary—The Faculty—Revival—Interest in Mis- sions—Licentiate—Considering Duty as to Missions- Decision—Delaware, Ohio—Delay in Going—Ordi- nation—Marriage—Going at Last. CHAPTER IV • * ^' Gone to the Front . • Hardships Bound to Shantung, China—The Voyage— for Che- and Trials on the Way—At Shanghai—Bound Shore- foo—Vessel on the Rocks—Wanderings on to Deliverance and Arrival at Chefoo—By Shentza Tengchow. -

Biblical Translations of Early Missionaries in East and Central Africa. I. Translations Into Swahili

ASIAN AND AFRICAN STUDIES, 15, 2006, 1, 80-89 BIBLICAL TRANSLATIONS OF EARLY MISSIONARIES IN EAST AND CENTRAL AFRICA. I. TRANSLATIONS INTO SWAHILI Viera Pawlikov A-V ilhanov A Institute of Oriental Studies, Slovak Academy of Sciences, Klemensova 19, 813 64 Bratislava, Slovakia e-mail: [email protected] Johann Ludwig Krapf, a German Lutheran in the service of the Anglican Church Missionary Society, was not only the first modem missionary in East Africa, he was a pioneer in the linguistic field and biblical translation work especially with regard to Swahili. A little later Bishop Edward Steere in Zanzibar translated into Swahili and published the New Testament and in 1891 the entire Bible. The pioneering linguistics of early missionaries, Ludwig Krapf, Bishop Steere and Father Sacleux set a high standard for a succession of Swahili experts and Steere’s Swahili Bible provided a basis for Biblical translations into other East African vernaculars. Key words: East and Central Africa, early Christian missionaries, Swahili, Bible translations. The first modem missionary who pioneered missionary work in East and Central Africa was Johann Ludwig Krapf, a German Lutheran from Württem berg, educated in Basel, who arrived in East Africa on 7 January 1844 in the service of the Anglican Church Missionary Society.1 Krapf joined the CMS to participate in new Protestant mission initiatives in Christian Ethiopia2 and he started his missionary career in the Tigré province in 1837. Unable to work there, he went instead to the Shoa kingdom where in 1839 he and his co-work ers were warmly received by the king, Sahle Selassie, only to be expelled in 1842 for political reasons. -

Table of Contents Upcoming AAHM Meetings

Table of contents • General Information • Participant Guide (Alphabetical List) • CME Information • Acknowledgements • Book Publishers’ Advertisements • Program Overview • AAHM Officers, Council, LAC and Program Committee • Sigerist Circle Program • AAHM Detailed Meeting Program • Abstracts Listed by Session • Information and Accommodations for Persons with Disabilities • Directions to Meeting Venues • Corrections and Modifications to Program Upcoming AAHM Meetings 2016 Minneapolis, 28 April – 1 May 2017 Nashville, 4 - 6 May Alphabetical List of Participants and Sessions PC = Program Committee; OP = Opening Plenary; GL = Garrison Lecture; FL = Friday Lunch; SL = Saturday Lunch; RW = Research Workshop; SS = Special Session; SC = Sigerist Circle; DF = Documentary Film Åhren, Eva – I1 De Borros, Juanitia – E1 Heitman, Kristin – FL1 Anderson, Warwick – OP, E1 DeMio , Michelle – F1 Herzberg, David – G3 Andrews, Bridie – D2 Dodman, Thomas – G2 Higby, Greg – B4 Apple, Rima – A5 Dong, Lorraine – I5 Hildebrandt, Sabine - C3 Downey, Dennis – E4 Hoffman, Beatrix – SC, I3 Baker, Jeffrey – A3 Downs, James – F2 Hogan, Andrew – C2 Barnes, Nicole – B5, C1, PC Dubois, Marc-Jacques –C4 Hogarth, Rana – H4 Barr, Justin – D4, E5 Duffin, Jacalyn – G1 Howell, Joel – I4 Barry, Samuel – A2 Dufour, Monique – A5 Huisman, Frank – F2 Bhattacharya, Nandini–D2 Dwyer, Ellen – E2 Humphreys, Margaret - OP,GL Bian, He – D2 Dwyer, Erica - A1 Birn, Anne-Emanuelle –H3 Dwyer, Michael – E2 Imada, Adria - C5 Bivins, Roberta – F5 Inrig, Stephen – PC, D1 Blibo, Frank – C4 Eaton, Nicole – A4 Bonnell-Freidin, Anne - B2 Eder, Sandra - C2 Johnson, Russell- RW Borsch, Stuart – E3 Edington, Claire – E1 Jones, David – C4 Boster, Dea – I4 Engelmann, Lukas – A1 Jones, Kelly – B4 Braslow, Joel – E4 Espinosa, Mariola – FL2, H4 Jones, Lori – E3 Braswell, Harold – C5 Evans, Bonnie – A2 Brown, Theodore M. -

The Christianization of the Nahua and Totonac in the Sierra Norte De

Contents Illustrations ix Foreword by Alfredo López Austin xvii Acknowledgments xxvii Chapter 1. Converting the Indians in Sixteenth- Century Central Mexico to Christianity 1 Arrival of the Franciscan Missionaries 5 Conversion and the Theory of “Cultural Fatigue” 18 Chapter 2. From Spiritual Conquest to Parish Administration in Colonial Central Mexico 25 Partial Survival of the Ancient Calendar 31 Life in the Indian Parishes of Colonial Central Mexico 32 Chapter 3. A Trilingual, Traditionalist Indigenous Area in the Sierra Norte de Puebla 37 Regional History 40 Three Languages with a Shared Totonac Substratum 48 v Contents Chapter 4. Introduction of Christianity in the Sierra Norte de Puebla 53 Chapter 5. Local Religious Crises in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries 63 Andrés Mixcoatl 63 Juan, Cacique of Matlatlán 67 Miguel del Águila, Cacique of Xicotepec 70 Pagan Festivals in Tutotepec 71 Gregorio Juan 74 Chapter 6. The Tutotepec Otomí Rebellion, 1766–1769 81 The Facts 81 Discussion and Interpretation 98 Chapter 7. Contemporary Traditions in the Sierra Norte de Puebla 129 Worship of Tutelary Mountains 130 Shrines and Sacred Constructions 135 Chapter 8. Sacred Drums, Teponaztli, and Idols from the Sierra Norte de Puebla 147 The Huehuetl, or Vertical Drum 147 The Teponaztli, or Female Drum 154 Ancient and Recent Idols in Shrines 173 Chapter 9. Traditional Indigenous Festivities in the Sierra Norte de Puebla 179 The Ancient Festival of San Juan Techachalco at Xicotepec 179 The Annual Festivity of the Tepetzintla Totonacs 185 Memories of Annual Festivities in Other Villages 198 Conclusions 203 Chapter 10. Elements and Accessories of Traditional Native Ceremonies 213 Oblations and Accompanying Rites 213 Prayers, Singing, Music, and Dancing 217 Ritual Idols and Figurines 220 Other Ritual Accessories 225 Chapter 11. -

Read Book Religion in the Ancient Greek City 1St Edition Kindle

RELIGION IN THE ANCIENT GREEK CITY 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Louise Bruit Zaidman | 9780521423571 | | | | | Religion in the Ancient Greek City 1st edition PDF Book Altogether the year in Athens included some days that were religious festivals of some sort, though varying greatly in importance. Some of these mysteries, like the mysteries of Eleusis and Samothrace , were ancient and local. Athens Atlanta, Georgia: Scholars Press. At some date, Zeus and other deities were identified locally with heroes and heroines from the Homeric poems and called by such names as Zeus Agamemnon. The temple was the house of the deity it was dedicated to, who in some sense resided in the cult image in the cella or main room inside, normally facing the only door. Historical religions. Christianization of saints and feasts Christianity and Paganism Constantinian shift Hellenistic religion Iconoclasm Neoplatonism Religio licita Virtuous pagan. Sacred Islands. See Article History. Sim Lyriti rated it it was amazing Mar 03, Priests simply looked after cults; they did not constitute a clergy , and there were no sacred books. I much prefer Price's text for many reasons. At times certain gods would be opposed to others, and they would try to outdo each other. An unintended consequence since the Greeks were monogamous was that Zeus in particular became markedly polygamous. Plato's disciple, Aristotle , also disagreed that polytheistic deities existed, because he could not find enough empirical evidence for it. Once established there in a conspicuous position, the Olympians came to be identified with local deities and to be assigned as consorts to the local god or goddess. -

African Missionary Heroes and Heroines

H * K 81632 C-JkV tN *.i v^, N KNOX COLLEGE TORONTO .. J. Six Lectures Given Before the College of Missions, Indianapolis, Indiana AFRICAN MISSIONARY HEROES AND HEROINES CAVIM KNOX COLLEGE TORONTO 81632. THE MACMILLAN COMPANY NEW YORK BOSTON CHICAGO DALLAS ATLANTA SAN FRANCISCO MACMILLAN & CO., LIMITED LONDON BOMBAY CALCUTTA MELBOURNE THE MACMILLAN CO. OF CANADA, LTD. TORONTO DUTY to God, and to our Fellow-men was the Rule of Life of David Livingstone a /eer written by Dr. Livingstone on September gth, 1857 to Miss MacGregor (daughter of General MacGregor). AFRICAN MISSIONARY HEROES AND HEROINES BY H. K. W. KUMM AUTHOR OF "FROM HAUSALAND TO EGYPT," "THE LANDS OF ETHIOPIA," "TRIBES OF THE NILE VALLEY," "THE NATIONAL ECONOMY OF NUBIA," "THE SUDAN" gorfe THE MACMILLAN COMPANY 1917 AH rights reserved COPYRIGHT, 1917, BY THE MACMILLAN COMPANY Set up and electrotyped Published, November, 1917 PREFACE Were it but possible in the time and space that can be given to this book to write of Stanley and Lavigerie the cardinal, of Gordon and Rhodesia Rhodes, of Bishop Hall and Hannington, of Thornton, Pilkington, and Andrew Murray, of Mary Kingsley, Mungo Park, and Samuel Baker, of Rebman, Schoen and Klein, of Barth and Nachtigal, of Denham, Junker, Overweg and Vogel, of Browne, and Speke, and Grant, and van der Decken, of Gordon Gumming, Arnot, Emin Pasha, of Madame Tinney, Schweinfurth and Selous, of Bishop Gobat and his Pilgrim Street to Abyssinia, of church-fathers, Cyril, Cyprian, and Athanasius, of Clement, Origen and Tertullian, and of the greatest of them St.