The Vulnerability of Mission*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CURRICULUM VITAE Morton Falk Goldberg, MD, FACS, FAOSFRACO

CURRICULUM VITAE Morton Falk Goldberg, M.D., F.A.C.S., F.A.O.S. F.R.A.C.O. (Hon), M.D. (Hon., University Coimbra) PERSONAL DATA: Born, June 8, 1937 Lawrence, MA, USA Married, Myrna Davidov 5/6/1968 Children: Matthew Falk Michael Falk EDUCATION: A.B., Biology – Magna cum laude, 1958 Harvard College, Cambridge MA Detur Prize, 1954-1955 Phi Beta Kappa, Senior Sixteen 1958 M.D., Medicine – Cum Laude 1962 Lehman Fellowship 1958-1962 Alpha Omega Alpha, Senior Ten 1962 INTERNSHIP: Department of Medicine, 1962-1963 Peter Bent Brigham Hospital, Boston, MA RESIDENCY: Assistant Resident in Ophthalmology 1963-1966 Wilmer Ophthalmological Institute, Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, MD CHIEF RESIDENT: Chief Resident in Ophthalmology Mar. 1966-Jun. 1966 Yale-New Haven Hospital Chief Resident in Ophthalmology, Jul. 1966-Jun. 1967 Wilmer Ophthalmological Institute Johns Hopkins Hospital BOARD CERTIFICATION: American Board of Ophthalmology 1968 Page 1 CURRICULUM VITAE Morton Falk Goldberg, M.D., F.A.C.S., F.A.O.S. F.R.A.C.O. (Hon), M.D. (Hon., University Coimbra) HONORARY DEGREES: F.R.A.C.O., Honorary Fellow of the Royal Australian 1962 College of Ophthalmology Doctoris Honoris Causa, University of Coimbra, 1995 Portugal MEDALS: Inaugural Ida Mann Medal, Oxford University 1980 Arnall Patz Medal, Macula Society 1999 Prof. Isaac Michaelson Medal, Israel Academy Of 2000 Sciences and Humanities and the Hebrew University- Hadassah Medical Organization David Paton Medal, Cullen Eye Institute and Baylor 2002 College of Medicine Lucien Howe Medal, American Ophthalmological -

David Paton: Christian Mission Encounters Communism in China

CHAPTER NINE DAVID PATON: CHRISTIAN MISSION ENCOUNTERS COMMUNISM IN CHINA While serving as a visiting fellow of Cambridge University, England in the fall of 2005, I was asked to lead a discussion group with Master of Philosophy students on Christianity in China for the Divinity Faculty. Amongst the reading references, I found David Paton’s book, Christian Mission and the Judgment of God.1 David Paton had been a CMS mis- sionary in China for 10 years and was expelled from China in 1951. So he had experienced the end of the missionary era in China in the early 1950s. The book was first published in 1953 and was reprinted by Wm B. Eerdmans Co. in October 1996 (after Paton’s death in 1992), with the addition of an introduction by Rev. Bob Whyte and a foreword by Bishop K.H. Ting. They both endorsed Paton’s view from the experiences of Chinese Churches in the past forty years. Bob Whyte reported that many of Paton’s reflections remained of immedi- ate relevance today and the issues he had perceived as important in 1953 were still central to any reflections on the future of Christianity in China. Bishop Ting also confirmed that this book was a book of pro- phetic vision and Paton was a gift from God to the worldwide church. Dr. Gerald H. Anderson, the Emeritus Director of Overseas Ministries Study Center at New Haven (USA) added a remark on the cover- page, saying: “To have this classic available again is timely—even bet- ter with the new foreword by Bishop K.H. -

Washington State University Ninety-Second Annual Commencement

WASHINGTON STATE UNIVERSITY NINETY-SECOND ANNUAL COMMENCEMENT May 7, 1988 Appc,JrJncc of :,1 narnc on thh progr;.un i,r,; prcs"i.11nptivc evidence (Jf gr:,~du;,1tiun ancl gr:,ldu.:r.Hion houors .. bur if n1usr. no!. in ;u1y sense he n-·g~1rdcd :.i.s conclusive. Tl1c dip(oni;i {){" 1"l'lc un..i1 1 (::r:-iiry) !•;.igni:·d ;ind ~1c11Jc(] by ii:; proper i..>\\iccrs, reiT\~-lin,•~ ihc ()('fici;l.l tc·stirnuny of i 1·1e 1·ios-1;css!on of rh,-· c!cgrcc The Commencement Procession Order of Exercises Presiding-Dr. Samuel Smith, President Processional Candidates for Advanced Degrees Washington State University Wind Symphony Professor L. Keating Johnson, Conductor University Faculty Posting of the Colors Regents of the University Army ROTC Color Guard The National Anthem Honored Guests of the University Washington State University Wind Symphony Dr. Jane Wyss, Song Leader President of the University Invocation Reverend Graham Owen Hutchins Simpson United Methodist Church Introduction of Commencement Speaker Dr. Samuel Smith Commencement Address The Honorable Thomas S. Foley President's Faculty Excellence Awards Dr. Albert C. Yates Executive Vice President and Provost Instruction: Gerald L. Young Research: Linda L. Randall Public Service: Thomas L. Barton Festival March by Giacomo Puccini Washington State University Wind Symphony Bachelors Degrees Advanced Degrees Alma Mater The Assembly SPECIAL NOTE FOR PARENTS AND FRIENDS: Professional Recessional photographers will photograph all candidates as they receive their diploma covers from the deans at the all-university and Washington State University Wind Symphony college commencement ceremonies. A photo will be mailed to each graduate, and additional photos may be purchased at reasonable rates. -

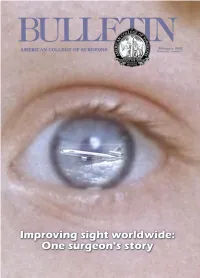

Bulletin February 2002

February 2002 Volume 87, Number 2 _________________________________________________________________ FEATURES Stephen J. Regnier Editor Surgeon takes flight to deliver improved sight worldwide 12 Walter J. Kahn, MD, FACS Linn Meyer Director of Communications Surgeons pocket PDAs to end paper chase: Part II 17 Karen Sandrick Diane S. Schneidman Senior Editor Liability premium increases may offer Tina Woelke opportunities for change 22 Graphic Design Specialist Christian Shalgian Alden H. Harken, Governors’ committee deals with range of risks 25 MD, FACS Donald E. Fry, MD, FACS Charles D. Mabry, MD, FACS Jack W. McAninch, A summary of the Ethics and Philosophy Lecture: Surgery—Is it an impairing profession? 29 MD, FACS Editorial Advisors Statement on bicycle safety and Tina Woelke the promotion of bicycle helmet use 30 Front cover design Tina Woelke Back cover design DEPARTMENTS About the cover... From my perspective Editorial by Thomas R. Russell, MD, FACS, ACS Executive Director 3 For the last 20 years, ORBIS, a not-for-profit orga- nization based in New York, FYI: STAT 5 NY, has been flying ophthal- mologists to developing lands Dateline: Washington 6 to treat blind and nearly Division of Advocacy and Health Policy blind patients and to train surgeons and other health care professionals in the pro- What surgeons should know about... 8 vision of advanced oph- OSHA regulation of blood-borne pathogens thalmic services. In “Sur- Adrienne Roberts geon takes flight to deliver improved sight worldwide,” p. 12, Walter J. Kahn, MD, Keeping current 32 FACS, discusses his experi- What’s new in ACS Surgery: Principles and Practice ences as a volunteer for Erin Michael Kelly ORBIS. -

Table of Contents Upcoming AAHM Meetings

Table of contents • General Information • Participant Guide (Alphabetical List) • CME Information • Acknowledgements • Book Publishers’ Advertisements • Program Overview • AAHM Officers, Council, LAC and Program Committee • Sigerist Circle Program • AAHM Detailed Meeting Program • Abstracts Listed by Session • Information and Accommodations for Persons with Disabilities • Directions to Meeting Venues • Corrections and Modifications to Program Upcoming AAHM Meetings 2016 Minneapolis, 28 April – 1 May 2017 Nashville, 4 - 6 May Alphabetical List of Participants and Sessions PC = Program Committee; OP = Opening Plenary; GL = Garrison Lecture; FL = Friday Lunch; SL = Saturday Lunch; RW = Research Workshop; SS = Special Session; SC = Sigerist Circle; DF = Documentary Film Åhren, Eva – I1 De Borros, Juanitia – E1 Heitman, Kristin – FL1 Anderson, Warwick – OP, E1 DeMio , Michelle – F1 Herzberg, David – G3 Andrews, Bridie – D2 Dodman, Thomas – G2 Higby, Greg – B4 Apple, Rima – A5 Dong, Lorraine – I5 Hildebrandt, Sabine - C3 Downey, Dennis – E4 Hoffman, Beatrix – SC, I3 Baker, Jeffrey – A3 Downs, James – F2 Hogan, Andrew – C2 Barnes, Nicole – B5, C1, PC Dubois, Marc-Jacques –C4 Hogarth, Rana – H4 Barr, Justin – D4, E5 Duffin, Jacalyn – G1 Howell, Joel – I4 Barry, Samuel – A2 Dufour, Monique – A5 Huisman, Frank – F2 Bhattacharya, Nandini–D2 Dwyer, Ellen – E2 Humphreys, Margaret - OP,GL Bian, He – D2 Dwyer, Erica - A1 Birn, Anne-Emanuelle –H3 Dwyer, Michael – E2 Imada, Adria - C5 Bivins, Roberta – F5 Inrig, Stephen – PC, D1 Blibo, Frank – C4 Eaton, Nicole – A4 Bonnell-Freidin, Anne - B2 Eder, Sandra - C2 Johnson, Russell- RW Borsch, Stuart – E3 Edington, Claire – E1 Jones, David – C4 Boster, Dea – I4 Engelmann, Lukas – A1 Jones, Kelly – B4 Braslow, Joel – E4 Espinosa, Mariola – FL2, H4 Jones, Lori – E3 Braswell, Harold – C5 Evans, Bonnie – A2 Brown, Theodore M. -

Chinese Christianity Religion in Chinese Societies

Chinese Christianity Religion in Chinese Societies Edited by Kenneth Dean, McGill University Richard Madsen, University of California, San Diego David Palmer, University of Hong Kong VOLUME 4 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.nl/rics Chinese Christianity An Interplay between Global and Local Perspectives By Peter Tze Ming Ng LEIDEN • BOSTON 2012 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Chinese Christianity : an interplay between global and local perspectives / by Peter Tze Ming Ng. p. cm. — (Religion in Chinese societies ; v. 4) Includes index. ISBN 978-90-04-22574-9 (hardback : alk. paper) 1. Christianity—China. 2. China—Religion. I. Wu, Ziming. II. Ng, Peter Tze Ming. BR1285.C527 2012 275.1’082—dc23 2011049458 ISSN 1877-6264 ISBN 978 90 04 22574 9 (hardback) ISBN 978 90 04 22575 6 (e-book) Copyright 2012 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Global Oriental, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Koninklijke Brill NV provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. Fees are subject to change. This book is printed on acid-free paper. CONTENTS Foreword ..................................................................................... vii Daniel H. Bays Foreword ..................................................................................... ix Philip Yuen Sang Leung Foreword .................................................................................... -

David Paton --- Christian Missiomissionn Encounters Communism in China"

THE HENRY MARTYN LECTURES 2007 "David Paton --- Christian MissioMissionn Encounters Communism in China" by Prof. Peter Tze Ming Ng LECTURE 2: Tuesday 6th February 2007 INTRODUCTION In this second lecture, I shall focus on my reflections of the work of David Paton, Christian Mission and the Judgment of God (London: SCM Press, First edition in 1953). When I came to Cambridge as a visiting fellow in the fall of 2005, I was asked to lead a discussion group at this Divinity Faculty. I was glad to know that amongst the reading list, Paton's book was on the required list for all M.Phil. students of World Christianity. The book was reprinted by Wm B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. in October 1996, with an introduction by Rev. Bob Whyte and a foreword by Bishop K.H. Ting. They both have endorsed Paton's view from the experiences of Chinese Churches in the past forty years. Bob Whyte said that many of Paton's reflections remained of immediate relevance today and the issues he perceived as important in 1953 were still central to the future Christianity in China. Bishop Ting also affirmed that his book was a book of prophetic vision and Paton was a gift of God to the worldwide church. Dr. Gerald H. Anderson, the director of Overseas Ministries Study Centre at New Haven (USA) further remarked, saying: "To have this classic available again is timely- even better with the new foreword by Bishop K.H. Ting. [1] So Paton's work was still worth re-visiting, and I decided to read it again for this lecture. -

Timothy Richard --- Christian Attitudes Towards Chinese Religions and Culture

Texts of Henry Martyn Lectures 2007 given at the Faculty of Divinity, University of Cambridge on 5th, 6th, 7th February 2007 "Three Prophetic Voices --- The Challenges of Christianity from Modern China" Prof Peter Ng The Chinese University of Hong Kong ••• Lecture I: Timothy Richard --- Christian Attitudes towards Chinese Religions and Culture ••• Lecture II: David Paton --- Christianity Encounters Communism ••• Lecture III: K.H. Ting --- Christianity and the ThreeThree----SelfSelf Church in China THE HENRY MARTYN LECTURES 2007 "Timothy Richard --- Christian Attitudes towards Chinese Religions and Culture" by Prof. Peter Tze Ming Ng LECTURE 1: Monday 5th February 2007 INTRODUCTION I am most honoured to be the Henry Martyn Lecturer of 2007 and most happy to present this lecture series on "Three Prophetic Voices- the Challenges of Christianity from Modern China", in special memory of the 200th anniversary of the arrival of Robert Morrison to China in 1807. As the theme assigned to this year's lecture is on "The Challenges of Christianity from Modern China", I have chosen three prophetic voices which are respectively from Timothy Richard, David Paton and K.H. Ting. Last October, when Dr. Rowan Williams, the Archbishop of Canterbury was paying a two-week visit to China, he made at one of his lectures in Nanjing the following remarks, saying: "China is emerging as a senior partner in the fellowship of nations; a country whose economy is changing so fast and whose profile in the world has become so recognisable and distinctive that we can't imagine a global future without the Chinese presence… (And he said to the students there) Yours is a society which will have messages to give to the rest of the world…" [1] About a year ago, in November 2005, Lord Wilson, the Master of Peterhouse spoke as the Lady Margaret Preacher at the Commemoration of Benefactors Sunday at our University Church, the Great St. -

OIE/FAO FMD Reference Laboratories Network Meeting Lanzhou, China, 15 – 19 September 2008 OIE/FAO Foot-And-Mouth Disease Reference Laboratories Par�Cipants Network

OIE/FAO Foot-and-Mouth Disease Reference Laboratories Network OIE/FAO FMD Reference Laboratories Network Meeting Lanzhou, China, 15 – 19 September 2008 OIE/FAO Foot-and-Mouth Disease Reference Laboratories Par�cipants Network David Paton OIE Reference Laboratory and FAO World Reference Laboratory for FMD, John Bashiruddin (Rapporteur) IAH-Pirbright, UK Yanmin Li Gaolatlhe Thobokwe OIE FMD Regional Reference Laboratory for the Sub-Saharan con�nent, Elliot Fana Botswana Keabetswe Maogabo Vladimir Borisov OIE Regional Reference Laboratory for FMD for Eastern Europe, Central Alexey Scherbakov Asia and Transcaucasia, FGI-ARRIAH, Russia Ingrid Bergmann FAO/OIE Reference Laboratory for FMD, Centro Panamericano de Fiebre A�osa OPS/OMS, Rio de Janeiro, Brasil Eduardo Maradei OIE Reference Laboratory for Foot and Mouth Disease, Laboratorio de Fiebre A�osa de la Dirección de Laboratorios y Control Técnico, Argen�n Belinda Blignaut FAO/OIE FMD Reference Laboratory, transboundary Animal Diseases Programme, ARC-Onderstepoort Veterinary Ins�tute, South Africa Samia Metwally FAO FMD Reference Laboratory, Foreign Animal Disease Diagnos�c Lab, Plum Island Animal Disease Center, Greenport, USA Kris De Clercq OIE collabora�ng centre for valida�on, quality assessment and quality Nesya Goris control of diagnos�c assays and vaccine tes�ng for vesicular diseases in Europe, CODA-CERVA-VAR, Ukkel, Belgium Xuepeng Cai, Youngguang Zhang, Na�onal FMD Laboratory, Lanzhou Veterinary Research Ins�tute, CAAS, Xiangtao Liu, Hong Yin, Zaixin Liu, Gansu, P. R. China Zengjun -

The Global Control Of

The Global control of FMD - Tools, ideas and ideals – Erice, Italy 14-17 October 2008 Appendix 2 LIST OF PARTICIPANTS Research Group members are listed together. Remaining participants are listed under “Others” in alphabetical order (by surname) and by “Country” at the end Open Session of the Research Group of the Standing Technical Committee Erice, Italy 14 - 17 October 2008 RESEARCH GROUP Tel: +90 312 2873600 / Fax: +90 312 2873606 Dr Aldo DEKKER (Chairman) Mobile: +90 533 3571484 Senior Scientist [email protected] Laboratory Vesicular Diseases Central Institute for Animal Disease Control Dr Georgi Kirilov GEORGIEV POBox 2004, Lelystad Head of Exotic and Emerging Diseases 8203 AA, The Netherlands National Diagnostic and Research Veterinary Tel/Fax: +31-320-238603 /+31-320-238668 Medical Institute e-mail: [email protected] 1606 Sofia, Bulgaria Tel/Fax: +359-2-8341004 Dr Kris DE CLERCQ (Vice Chairman) e-mail: [email protected] Head Department of Virology Dr Bernd HAAS Section Epizootic Diseases Head of National FMD Reference Laboratory CODA-CERVA-VAR Friedrich-Loeffler-Institut Groeselenberg 99 Federal Research Institute for Animal Health B-1180 Ukkel, Belgium Boddenblick 5 a Tel/Fax: +32-2-3790400 / +32-2-3790666 17493 Greifswald, Insel Riems, Germany e-mail: [email protected] Tel/Fax: +49-(0)3835170 /+49- (0)383517151 Dr Søren ALEXANDERSEN e-mail: [email protected] Research Professor Danish Institute for Food and Veterinary Dr Stephan ZIENTARA Research AFSSA – Lerpaz - BP 67 Department of Virology, Lindholm 94703 Maisons-Alfort Cedex, France DK-4771, Kalvehave, Denmark Tel/Fax: +33-1-49-771333 /+33-1-43- Tel/Fax: +45-72-347833 / +45-72-347883 689762 (direct) or 347901 [email protected] e-mail: [email protected] Dr Hagai YADIN Dr Emiliana BROCCHI Head of Virology Division and Head FMD Laboratory National Reference Laboratory for Vesicular Kimron Veterinary Institute Diseases c/o Ministry of Agriculture Istituto Zooprofilattico Sperimentale della POBox 12 Lombardia e dell’Emilia Romagna Beit-Dagan 50250, Israel Via A. -

EVE & the FIRE HORSE a Film by Julia Kwan

EVE & THE FIRE HORSE A film by Julia Kwan (2005, Canada, 92 min.) Distribution 1028 Queen Street West Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M6J 1H6 Tel: 416-516-9775 Fax: 416-516-0651 E-mail: [email protected] www.mongrelmedia.com Publicity Bonne Smith Star PR Tel: 416-488-4436 Fax: 416-488-8438 E-mail: [email protected] High res stills may be downloaded from http://www.mongrelmedia.com/press.html EVE & THE FIRE HORSE LONG SYNOPSIS Eve, a precocious nine year-old with an overactive imagination, was born in the year of the Fire Horse, notorious among Chinese families for producing the most troublesome children. Dinners around Eve’s family table are a raucous affair, where old world propriety and new world audacity mix in even measure. But as summer approaches, it seems like Eve’s carefree childhood days are behind her. When her mother chops down their apple tree — a superstitious omen — bad luck worms its way into their family in unexpected, tragic ways. Forced to grow up too fast, Eve learns to take pleasure in life’s small gifts — like a goldfish she believes to be the reincarnated spirit of her beloved grandmother. Meanwhile, Eve’s older sister Karena is going through changes of her own, exploring a newfound fascination with Christianity. Soon, crucifixes pop up next to the Buddha in the family’s house and Eve must contend with a Sunday school class where her wild imagination is distinctly out of place. Caught between her sister’s quest for premature sainthood and her own sense of right and wrong, Eve faces the challenges of childhood with fanciful humour and wide-eyed wonder. -

FULL ISSUE (48 Pp., 2.2 MB PDF)

Vol. 9, No.3 nternatlona• July 1985 etln• Resources for Mission Research .What is past is prologue," Shakespeare tells us in The Tem pest, and his words are inscribed on the east pedestal of the National Archives Building in Washington, D.C. Too often those engaged in mission have hurried on to,new projects without consulting the wisdom of past experience, and all have been the On Page poorer for it. In this issue, we call attention to a few examples of the multitudinous resources available for mission research, to en 98 Theological Mass Movements in China able us to understand better our path to the future. K. H. Ting K. H. Ting tells how Chinese Christians were often caught short in evaluating the revolutionary changes through which 104 Resources for China Mission Research China has passed in recent years. He shows how theological mass Martha Lund Smalley and Stephen L. Peterson movements in his country opened up deeper appreciation for Paul A. Ericksen worthwhile traditions of China's past, as well as for the gospel's Archie R. Crouch joyous reception among the poor and the oppressed. David E. Mungello As promised in our last issue on China Mission History, we are featuring four additional reports on projects of China Mission 110 IIAnd Brought Forth Fruit an Hundredfold": Research. Clearly, what missionaries and Chinese Christian lead Sharing Western Documentation Resources with ers have learned from the joys and pains of their experiences will the Third World by Microfiche illumine future Christian witness in China and in many other Harold W.