David Paton --- Christian Missiomissionn Encounters Communism in China"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CURRICULUM VITAE Morton Falk Goldberg, MD, FACS, FAOSFRACO

CURRICULUM VITAE Morton Falk Goldberg, M.D., F.A.C.S., F.A.O.S. F.R.A.C.O. (Hon), M.D. (Hon., University Coimbra) PERSONAL DATA: Born, June 8, 1937 Lawrence, MA, USA Married, Myrna Davidov 5/6/1968 Children: Matthew Falk Michael Falk EDUCATION: A.B., Biology – Magna cum laude, 1958 Harvard College, Cambridge MA Detur Prize, 1954-1955 Phi Beta Kappa, Senior Sixteen 1958 M.D., Medicine – Cum Laude 1962 Lehman Fellowship 1958-1962 Alpha Omega Alpha, Senior Ten 1962 INTERNSHIP: Department of Medicine, 1962-1963 Peter Bent Brigham Hospital, Boston, MA RESIDENCY: Assistant Resident in Ophthalmology 1963-1966 Wilmer Ophthalmological Institute, Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, MD CHIEF RESIDENT: Chief Resident in Ophthalmology Mar. 1966-Jun. 1966 Yale-New Haven Hospital Chief Resident in Ophthalmology, Jul. 1966-Jun. 1967 Wilmer Ophthalmological Institute Johns Hopkins Hospital BOARD CERTIFICATION: American Board of Ophthalmology 1968 Page 1 CURRICULUM VITAE Morton Falk Goldberg, M.D., F.A.C.S., F.A.O.S. F.R.A.C.O. (Hon), M.D. (Hon., University Coimbra) HONORARY DEGREES: F.R.A.C.O., Honorary Fellow of the Royal Australian 1962 College of Ophthalmology Doctoris Honoris Causa, University of Coimbra, 1995 Portugal MEDALS: Inaugural Ida Mann Medal, Oxford University 1980 Arnall Patz Medal, Macula Society 1999 Prof. Isaac Michaelson Medal, Israel Academy Of 2000 Sciences and Humanities and the Hebrew University- Hadassah Medical Organization David Paton Medal, Cullen Eye Institute and Baylor 2002 College of Medicine Lucien Howe Medal, American Ophthalmological -

Sir David P. Cuthbertson (190&1989)

Downloaded from British Journal of Nutrition, Vol. 63, No. 1 https://www.cambridge.org/core . IP address: 170.106.34.90 , on 03 Oct 2021 at 14:36:48 , subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms . https://doi.org/10.1079/BJN19900085 DAVlD P. CUTHBERTSON (Facing p. I) Downloaded from British Journal of Nutrition (1990). 63, 14 1 https://www.cambridge.org/core Obituary Notice SIR DAVID P. CUTHBERTSON (190&1989) . IP address: David Paton Cuthbertson CBE, MD, DSc, FRSE, a past President of the Nutrition Society, a previous Editor of the British Journal of Nutrition, and for 20 years Director of the Rowett Research Institute, died on 15 April 1989-a few weeks before his 89th birthday. He was born in Kilmarnock, Ayrshire, and educated at Kilmarnock Academy 170.106.34.90 and the University of Glasgow from which he first graduated BSc in Chemistry in 1921, having been awarded the Doby-Smith gold medal. On graduation the Scottish Board of Agriculture awarded him a research scholarship to undertake work in chemistry in Dundee. , on However, this was initially deferred and then declined because he was influenced to study 03 Oct 2021 at 14:36:48 medicine by Professor E. P. Cathcart, FRS, well-known for his work in nutrition. He graduated MBChB in 1926, having won the Hunter medal in Physiology and a Strang-Steel scholarship for research. The latter enabled him to carry out research during vacations which led to his first publication, on ‘The distribution of phosphorus in muscle’, in the Biochemical Journal in 1925. -

David Paton: Christian Mission Encounters Communism in China

CHAPTER NINE DAVID PATON: CHRISTIAN MISSION ENCOUNTERS COMMUNISM IN CHINA While serving as a visiting fellow of Cambridge University, England in the fall of 2005, I was asked to lead a discussion group with Master of Philosophy students on Christianity in China for the Divinity Faculty. Amongst the reading references, I found David Paton’s book, Christian Mission and the Judgment of God.1 David Paton had been a CMS mis- sionary in China for 10 years and was expelled from China in 1951. So he had experienced the end of the missionary era in China in the early 1950s. The book was first published in 1953 and was reprinted by Wm B. Eerdmans Co. in October 1996 (after Paton’s death in 1992), with the addition of an introduction by Rev. Bob Whyte and a foreword by Bishop K.H. Ting. They both endorsed Paton’s view from the experiences of Chinese Churches in the past forty years. Bob Whyte reported that many of Paton’s reflections remained of immedi- ate relevance today and the issues he had perceived as important in 1953 were still central to any reflections on the future of Christianity in China. Bishop Ting also confirmed that this book was a book of pro- phetic vision and Paton was a gift from God to the worldwide church. Dr. Gerald H. Anderson, the Emeritus Director of Overseas Ministries Study Center at New Haven (USA) added a remark on the cover- page, saying: “To have this classic available again is timely—even bet- ter with the new foreword by Bishop K.H. -

Evangelical Review of Theology

EVANGELICAL REVIEW OF THEOLOGY VOLUME 12 Volume 12 • Number 1 • January 1988 Evangelical Review of Theology Articles and book reviews original and selected from publications worldwide for an international readership for the purpose of discerning the obedience of faith GENERAL EDITOR: SUNAND SUMITHRA Published by THE PATERNOSTER PRESS for WORLD EVANGELICAL FELLOWSHIP Theological Commission p. 2 ISSN: 0144–8153 Vol. 12 No. 1 January–March 1988 Copyright © 1988 World Evangelical Fellowship Editorial Address: The Evangelical Review of Theology is published in January, April, July and October by the Paternoster Press, Paternoster House, 3 Mount Radford Crescent, Exeter, UK, EX2 4JW, on behalf of the World Evangelical Fellowship Theological Commission, 57, Norris Road, P.B. 25005, Bangalore—560 025, India. General Editor: Sunand Sumithra Assistants to the Editor: Emmanuel James and Beena Jacob Committee: (The Executive Committee of the WEF Theological Commission) Peter Kuzmič (Chairman), Michael Nazir-Ali (Vice-Chairman), Don Carson, Emilio A. Núñez C., Rolf Hille, René Daidanso, Wilson Chow Editorial Policy: The articles in the Evangelical Review of Theology are the opinions of the authors and reviewers and do not necessarily represent those of the Editor or Publisher. Subscriptions: Subscription details appear on page 96 p. 3 2 Editorial Christ, Christianity and the Church As history progresses and the historical Jesus becomes more distant, every generation has the right to (and must) question his contemporary relevance—and hence also that of Christianity and the Church. The articles and book reviews in this issue generally deal with this relevance. Of the three, of course the questions about Jesus Christ are the basic ones. -

Washington State University Ninety-Second Annual Commencement

WASHINGTON STATE UNIVERSITY NINETY-SECOND ANNUAL COMMENCEMENT May 7, 1988 Appc,JrJncc of :,1 narnc on thh progr;.un i,r,; prcs"i.11nptivc evidence (Jf gr:,~du;,1tiun ancl gr:,ldu.:r.Hion houors .. bur if n1usr. no!. in ;u1y sense he n-·g~1rdcd :.i.s conclusive. Tl1c dip(oni;i {){" 1"l'lc un..i1 1 (::r:-iiry) !•;.igni:·d ;ind ~1c11Jc(] by ii:; proper i..>\\iccrs, reiT\~-lin,•~ ihc ()('fici;l.l tc·stirnuny of i 1·1e 1·ios-1;css!on of rh,-· c!cgrcc The Commencement Procession Order of Exercises Presiding-Dr. Samuel Smith, President Processional Candidates for Advanced Degrees Washington State University Wind Symphony Professor L. Keating Johnson, Conductor University Faculty Posting of the Colors Regents of the University Army ROTC Color Guard The National Anthem Honored Guests of the University Washington State University Wind Symphony Dr. Jane Wyss, Song Leader President of the University Invocation Reverend Graham Owen Hutchins Simpson United Methodist Church Introduction of Commencement Speaker Dr. Samuel Smith Commencement Address The Honorable Thomas S. Foley President's Faculty Excellence Awards Dr. Albert C. Yates Executive Vice President and Provost Instruction: Gerald L. Young Research: Linda L. Randall Public Service: Thomas L. Barton Festival March by Giacomo Puccini Washington State University Wind Symphony Bachelors Degrees Advanced Degrees Alma Mater The Assembly SPECIAL NOTE FOR PARENTS AND FRIENDS: Professional Recessional photographers will photograph all candidates as they receive their diploma covers from the deans at the all-university and Washington State University Wind Symphony college commencement ceremonies. A photo will be mailed to each graduate, and additional photos may be purchased at reasonable rates. -

The Weekly Prayer Meeting

Websites www.reformation-today.org The editor's personal website is http://www.errollhulse.com http://africanpastorsconference.com Th e photo above was taken at the SOLAS Conference in the Ntherlands (see page2). From lefi to right Bert Boer (pastor of a Baptist church in Deventer), Jeroen Bo! (chairman of the Geo1ge Whitefield Foundation), Gijs de Bree (pastor of a Baptist church in Kampen), Erroll Hulse, George van der Hoff (pastor of a Baptist church in Ede), Kees van Kralingen (elder of a Baptist church in Papendrecht), Erik Bouman (pastor of a Baptist church in Genk, Belgium), Michael Gorsira (pastor of a Baptist church in Delfz.ijl - also chairman of the Sola 5 Baptist committee) and Oscar Lohuis (itinerant preacher). 'THE GIFT' Readers of the previous two issues of Reformation Today wi ll be interested to learn that Chapel Library have published a 16 page booklet summarising the life and conversion of Charles Chiniquy. Free copies of this booklet are available to readers of Reformation Today. Please contact Chapel Libra1y directly if you live in the USA. .. (Chapel Library; 2603 W. Wright St., Pensacola, FL 32505; [email protected]). Other readers should contact Frederick Hodgson (See back inside cover). Front cover picture - Stephen Nowak preaching at a meeting in Tan zania (see report page 31). ii Editorial In a parish church near Berthelsdorf, Germany, during a special Wednesday 1 morning service, 13 " August 1727, there was an outpouring of the Holy Spirit. Paiiicipants left that meeting, 'hardly knowing whether they belonged to earth or had already gone to heaven'. One of them wrote, 'A great hunger after the Word of God took possession of us so that we had to have three services every day 5.00 am and 7.30 am and 9.00 pm.' The outstanding zeal for missionary work by the Moravians, as they became known, is described in the article Moravians and Missionary Passion. -

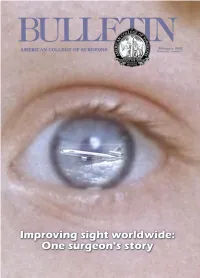

Bulletin February 2002

February 2002 Volume 87, Number 2 _________________________________________________________________ FEATURES Stephen J. Regnier Editor Surgeon takes flight to deliver improved sight worldwide 12 Walter J. Kahn, MD, FACS Linn Meyer Director of Communications Surgeons pocket PDAs to end paper chase: Part II 17 Karen Sandrick Diane S. Schneidman Senior Editor Liability premium increases may offer Tina Woelke opportunities for change 22 Graphic Design Specialist Christian Shalgian Alden H. Harken, Governors’ committee deals with range of risks 25 MD, FACS Donald E. Fry, MD, FACS Charles D. Mabry, MD, FACS Jack W. McAninch, A summary of the Ethics and Philosophy Lecture: Surgery—Is it an impairing profession? 29 MD, FACS Editorial Advisors Statement on bicycle safety and Tina Woelke the promotion of bicycle helmet use 30 Front cover design Tina Woelke Back cover design DEPARTMENTS About the cover... From my perspective Editorial by Thomas R. Russell, MD, FACS, ACS Executive Director 3 For the last 20 years, ORBIS, a not-for-profit orga- nization based in New York, FYI: STAT 5 NY, has been flying ophthal- mologists to developing lands Dateline: Washington 6 to treat blind and nearly Division of Advocacy and Health Policy blind patients and to train surgeons and other health care professionals in the pro- What surgeons should know about... 8 vision of advanced oph- OSHA regulation of blood-borne pathogens thalmic services. In “Sur- Adrienne Roberts geon takes flight to deliver improved sight worldwide,” p. 12, Walter J. Kahn, MD, Keeping current 32 FACS, discusses his experi- What’s new in ACS Surgery: Principles and Practice ences as a volunteer for Erin Michael Kelly ORBIS. -

Oracle: ORU Student Newspaper Oral Roberts University Collection

Oral Roberts University Digital Showcase Oracle: ORU Student Newspaper Oral Roberts University Collection 2-22-1974 Oracle (Feb 22, 1974) Holy Spirit Research Center ORU Library Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalshowcase.oru.edu/oracle Part of the Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, Christianity Commons, and the Higher Education Commons 'Show Me Jesus!' hqils tomorrow rhe by kot wolker And Roger has "friends" who are more than willing to show him Stone Productions, which pre- how to ease his troubled search- last serted Have A Nice Day ing. How about Drugs? As- 1, semester, will present Show Me! trology? Meditation? Somewhe¡e tomorrow evening at 8 in Howard there has to be an answer! Auditorium. Show Me! is a new Jon Stemkoski, Executive Di- kind of musical about Jesus, rector for Stone Productions, has which features Roger Sharp and featured several outstanding hits Vo|ume 9, NumbeT I7 ORAL RoBÉRTS UNIVERSITY, TULSA, oKLAHoMA Februory 22,1974 Stephanie Boosahda in the leading since Stone Productions began in roles with Jim Sharp, Michie Ep- April 1973. First featured was 1/'s stein, and Andy Melilli in the sup- Gettíng Late, a musical about porting roles. the end time and the Lord's re- Show Me! has the nerve to turn. Hal Lindsey, author of poke fun at the hypocrisy in the The Late Great Pianet Earth, was establishment churches of today. also featured. But it also shows how beautiful Stone Productions is a non- a life becomes when the Lord profit, student organization for is in it and when the person be- the purpose of witnessing about gins witnessing in earnest. -

Table of Contents Upcoming AAHM Meetings

Table of contents • General Information • Participant Guide (Alphabetical List) • CME Information • Acknowledgements • Book Publishers’ Advertisements • Program Overview • AAHM Officers, Council, LAC and Program Committee • Sigerist Circle Program • AAHM Detailed Meeting Program • Abstracts Listed by Session • Information and Accommodations for Persons with Disabilities • Directions to Meeting Venues • Corrections and Modifications to Program Upcoming AAHM Meetings 2016 Minneapolis, 28 April – 1 May 2017 Nashville, 4 - 6 May Alphabetical List of Participants and Sessions PC = Program Committee; OP = Opening Plenary; GL = Garrison Lecture; FL = Friday Lunch; SL = Saturday Lunch; RW = Research Workshop; SS = Special Session; SC = Sigerist Circle; DF = Documentary Film Åhren, Eva – I1 De Borros, Juanitia – E1 Heitman, Kristin – FL1 Anderson, Warwick – OP, E1 DeMio , Michelle – F1 Herzberg, David – G3 Andrews, Bridie – D2 Dodman, Thomas – G2 Higby, Greg – B4 Apple, Rima – A5 Dong, Lorraine – I5 Hildebrandt, Sabine - C3 Downey, Dennis – E4 Hoffman, Beatrix – SC, I3 Baker, Jeffrey – A3 Downs, James – F2 Hogan, Andrew – C2 Barnes, Nicole – B5, C1, PC Dubois, Marc-Jacques –C4 Hogarth, Rana – H4 Barr, Justin – D4, E5 Duffin, Jacalyn – G1 Howell, Joel – I4 Barry, Samuel – A2 Dufour, Monique – A5 Huisman, Frank – F2 Bhattacharya, Nandini–D2 Dwyer, Ellen – E2 Humphreys, Margaret - OP,GL Bian, He – D2 Dwyer, Erica - A1 Birn, Anne-Emanuelle –H3 Dwyer, Michael – E2 Imada, Adria - C5 Bivins, Roberta – F5 Inrig, Stephen – PC, D1 Blibo, Frank – C4 Eaton, Nicole – A4 Bonnell-Freidin, Anne - B2 Eder, Sandra - C2 Johnson, Russell- RW Borsch, Stuart – E3 Edington, Claire – E1 Jones, David – C4 Boster, Dea – I4 Engelmann, Lukas – A1 Jones, Kelly – B4 Braslow, Joel – E4 Espinosa, Mariola – FL2, H4 Jones, Lori – E3 Braswell, Harold – C5 Evans, Bonnie – A2 Brown, Theodore M. -

Some Ideas on the Direction of Chinese Theological Development

July-August 1969 Vol. XX, No.6 Library IlJ ~ 1 fj r,,,t<lw dYl al J 2 0t ll ~ ,lr ~ c tJ Ne w Yo r k . N Y 10 (,;,/ 1"If' p ii ollc (Arc" ;'>12) (,0 2 71 0 0 Subscription: $3 a year; 1-15 copies, 35¢ Edrtonat Otfice liol liO b / R. 47 5 Rl vcrSlclc Dr rve. New Yu rk N Y I OI)?1 each; 16-50 copies, 25¢ each; l ctepno ne (A red :' I ? ) H70 ? 1 / 5 Circulation OHice (,3 7 We" 1251 11 st .. Ncv. Yor k. N Y 100 21 more than 50 copies, 15¢ each re leph o ne ( Area :'12) 8,0 2') 10 SOME IDEAS ON THE DIRECTION OF CHINESE THEOLOGICAL DEVELOPMENT (An analysis of the features contributing to the lack of Chinese theologi cal productivity and a presentation of some ideas on the biblical direction of Chinese theological development; together with a preliminary bibliogra phy. (Since the beginning of the Cultural Revolution in August 1966, there has been no word of any theological activity in mainland China. The last re maining theological center, Nanking Theological Seminary, has been closed.) Jonathan Tien-En Chao'" I. INTRODUCTION In recent years t he r e has been a gr owi ng interest within the Chinese Christian community in the a reas of "Chi nese native-colored theology," the relationship between Christianity and Chinese cul t ure, the appropriateness of Chinese foreign missions projects, and the "indigenous church." These topics usually arouse peculiar interest among most Chinese Christians. Their central appeal is to the concept of the dis tinctly indigenous "Chinese" approach. -

Chinese Christianity Religion in Chinese Societies

Chinese Christianity Religion in Chinese Societies Edited by Kenneth Dean, McGill University Richard Madsen, University of California, San Diego David Palmer, University of Hong Kong VOLUME 4 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.nl/rics Chinese Christianity An Interplay between Global and Local Perspectives By Peter Tze Ming Ng LEIDEN • BOSTON 2012 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Chinese Christianity : an interplay between global and local perspectives / by Peter Tze Ming Ng. p. cm. — (Religion in Chinese societies ; v. 4) Includes index. ISBN 978-90-04-22574-9 (hardback : alk. paper) 1. Christianity—China. 2. China—Religion. I. Wu, Ziming. II. Ng, Peter Tze Ming. BR1285.C527 2012 275.1’082—dc23 2011049458 ISSN 1877-6264 ISBN 978 90 04 22574 9 (hardback) ISBN 978 90 04 22575 6 (e-book) Copyright 2012 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Global Oriental, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Koninklijke Brill NV provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. Fees are subject to change. This book is printed on acid-free paper. CONTENTS Foreword ..................................................................................... vii Daniel H. Bays Foreword ..................................................................................... ix Philip Yuen Sang Leung Foreword .................................................................................... -

The Gospel in China - 1920-1930

Websites www.reforrn ation-today.org The editor's personal website is http://www.erro ll hulse.com http ://africanpastorsconference.com Heritage Baptist Church, Owensboro, Kentucky, is referred to in the editorial and her ministries described in the article Encouragementfiwn Owensboro. Group photo taken at the Afi"ican Pastors' Conference in Barberton, South Afhca, see News, page 8. Front cover picture - Students.fi·om Back to the Bible College, near Barberton, South Africa, participated in the recent African Pastors' Conference. The Makhonjwa mountains can be seen in the background. For report see News, page 8. II Editorial During the discussion time at the Banner ofTruth Leicester Conference for ministers in May Geoff Thomas posed this question: Why, he asked, did the Reformed movement which was flying high in the 1970s lose its momentum? One answer given was the distraction of the charismatic movement. Attracted by 'higher' and far more exciting forms of worship and by the claim of signs, wonders and miracles (which seldom if ever eventuate) droves of young people moved away from the Reformed churches. Westminster Chapel, London, now a New Frontiers Church, is one example of what took place. Failure to face the challenge of contemporaneity (the worship wars) led to the loss of many young people and families. Today the situation in the UK is worse than ever with many small Reformed ageing churches in decline and heading toward closure. The main reason is the failure to distinguish between essential truths, important truths and phantom truths. Phantom truths refer to matters which cannot be supported by Scripture and may refer such things as dress codes, musical instruments, flower arrangements, architecture, or the order of a worship service.