Graphic Packaging Corporation V. Susan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Re-Writing the Script : Representations of Transgender Creativity In

Kate Norbury Re-writing the Script: Representations of Transgender Creativity in Contemporary Young Adult Fiction and Television Abstract: The transgender, gender-atypical or intersex protagonist challeng- es normative assumptions and expectations about gender, identity and sexu- ality. This article argues that contemporary transgender-themed young adult fiction and television uses the theme of creativity or the creative achievement script to override previously negative representations of adolescent transgender subjectivities. I consider three English-language novels and one television series for young adults and use script theory to analyse these four texts. Cris Beam’s I Am J (2011) and Kirstin Cronn-Mills’ Beautiful Music for Ugly Children (2012), both originally published in the United States, depict female to male transitions. Alyssa Brugman’s Alex As Well (2013), originally published in Australia, foregrounds the experience of an inter- sex teenager, Alex, raised as a boy, but who, at the age of fourteen, decides she is female. Glee introduced the transgender character Unique in 2012, and in 2014 she continued to be a central member of the New Directions choir. The Swedish graphic novel, Elias Ericson’s Åror (Oars, 2013), includes two transgender characters who enact the creative achievement script and fall in love with each other. Ericson’s graphic novel goes further than the English-language texts to date. Collectively, these transgender, gender-atypical or intersex protagonists and central characters assert their creativity and individual agency. The transgender character’s particular cre- ativity ultimately secures a positive sense of self. This more recent selection of texts which date from 2011 validate young adult transgender experience and model diversity and acceptance. -

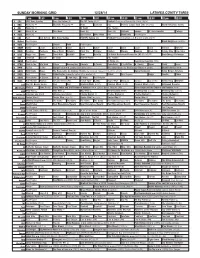

Sunday Morning Grid 12/28/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 12/28/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Chargers at Kansas City Chiefs. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News 1st Look Paid Premier League Goal Zone (N) (TVG) World/Adventure Sports 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Outback Explore St. Jude Hospital College 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Philadelphia Eagles at New York Giants. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Black Knight ›› (2001) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Simply Ming Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Play. Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Ed Slott’s Retirement Rescue for 2014! (TVG) Å BrainChange-Perlmutter 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) República Deportiva (TVG) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Tu Dia Tu Dia Happy Feet ››› (2006) Elijah Wood. -

Trinity Support Asked for WSSF to Help Needy Students Abroad

TRI , , ft t Volume XLV HARTFORD, CONN., DECEMBER 17, 1947 Number 10 Trinity Support Asked for WSSF Boosters Club to Trinity Basketeers Overwhelm Sponsor Pre-Xmas To Help Needy Students Abroad Williams in Home Debut, 58-36 I Dance This Evening Kitchen Describes Large Crowd Expected I I Ron Watson High Scorer Conditions; Drive Debaters Defeat At Festivities; Pipes Stassen Interviewed As Ephmen Succumb I Begins in January Haverford in Octet to Entertain By "Tdpod" Reporter At State Armory Speaking in Wednesday's Chapel This evening at 8:30 an informal By Bill Wetter service, Mr. Wilmer J. Kitchen asked Opening Battle pre-Christmas dance will be held in At Yale Meeting 1 I Trinity's support in a drive to give Cook Lounge and Hamlin Dining Hall An estimated crowd of 1600 watched Taking the negative side of the On Monday afternoon, December 8, 400,000 students abroad direly needed to help get the vacation off to a flying Trinity bounce back from its defeat question "Should the United States food, clothes, shelter, and hospitaliza start. The dance will be sponsored by about one hundred collegiate and pro- by M.I.T. earlier in the week, to romp Adopt Universal Military Training?", tion. Mr. Kitchen, Executive Secre the increasingly active Boosters Club. fessional newspaper reporters gath over the Ephmen of Williams to the I the Trinity debating team of David tary of the Wedel Student Service Music will be by Ed Lally, his piano e1·ed at the "Yale Daily News" build tune of 58 to 36, at the State Armory Rivkin and Samuel Goldstein opened Fund, said that due to crop failures and his orchestra, and refreshments last Saturday night. -

Walpole Public Library DVD List A

Walpole Public Library DVD List [Items purchased to present*] Last updated: 9/17/2021 INDEX Note: List does not reflect items lost or removed from collection A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z Nonfiction A A A place in the sun AAL Aaltra AAR Aardvark The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.1 vol.1 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.2 vol.2 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.3 vol.3 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.4 vol.4 ABE Aberdeen ABO About a boy ABO About Elly ABO About Schmidt ABO About time ABO Above the rim ABR Abraham Lincoln vampire hunter ABS Absolutely anything ABS Absolutely fabulous : the movie ACC Acceptable risk ACC Accepted ACC Accountant, The ACC SER. Accused : series 1 & 2 1 & 2 ACE Ace in the hole ACE Ace Ventura pet detective ACR Across the universe ACT Act of valor ACT Acts of vengeance ADA Adam's apples ADA Adams chronicles, The ADA Adam ADA Adam’s Rib ADA Adaptation ADA Ad Astra ADJ Adjustment Bureau, The *does not reflect missing materials or those being mended Walpole Public Library DVD List [Items purchased to present*] ADM Admission ADO Adopt a highway ADR Adrift ADU Adult world ADV Adventure of Sherlock Holmes’ smarter brother, The ADV The adventures of Baron Munchausen ADV Adverse AEO Aeon Flux AFF SEAS.1 Affair, The : season 1 AFF SEAS.2 Affair, The : season 2 AFF SEAS.3 Affair, The : season 3 AFF SEAS.4 Affair, The : season 4 AFF SEAS.5 Affair, -

PLANNING COMMISSION MINUTES 2004 PLANNING COMMISSION MINUTES 2004 Table of Contents January 22, 2004, 12:00 P.M

PLANNING COMMISSION MINUTES 2004 PLANNING COMMISSION MINUTES 2004 Table of Contents January 22, 2004, 12:00 p.m..............................................................................................................................1 February 17, 2004, 12:00 p.m..........................................................................................................................59 March 15, 2004, 12:00 p.m...............................................................................................................................78 April 19, 2004, 12:00 p.m................................................................................................................................127 May 17, 2004, 12:00 p.m.................................................................................................................................219 June 21, 2004, 12:00 p.m................................................................................................................................272 July 19, 2004, 10:00 p.m.................................................................................................................................367 August 16, 2004, 10:00 p.m............................................................................................................................446 September 23, 2004, 10:00 a.m......................................................................................................................518 October 18, 2004, 12:00 p.m...........................................................................................................................577 -

2021-2022 Catalog.Pdf

SEMINOLE STATE COLLEGE CATALOG 2021-22 2701 Boren Boulevard Seminole, OK 74868 405.382.9950 www.sscok.edu The regulations in this catalog are based upon present conditions and are subject to change without notice. The College reserves the right to modify any statement in accordance with unforeseen conditions. PRESIDENT’S WELCOME Dear Student, Welcome and congratulations on choosing Seminole State College. You have made an excellent decision regarding your academic career. The College is in a constant state of change. With expanding course options, state-of-the-art facilities, and knowledgeable faculty and staff, we provide a dynamic learning atmosphere. Seminole State College provides its students not only with an exceptional learning environment, but also a variety of extracurricular activities. In addition to the experience and training received in the classroom, student organizations offer a number of social and recreational activities. I hope you will enjoy the sporting events and community service opportunities presented to you. Involvement in these types of activities will enrich your college experience. Again, welcome to Seminole State College. We are proud you have selected our campus community as the next step in your education. Best Wishes, Lana Reynolds President i 2021-22 SEMINOLE STATE COLLEGE CATALOG Table of Contents Section I General Information ............................................................................ 1 Section II Admissions Information..................................................................... -

Reporting from a Video Game Industry in Transition, 2003 – 2011

Save Point Reporting from a video game industry in transition, 2003 – 2011 Kyle Orland Carnegie Mellon University: ETC Press Pittsburgh, PA Save Point: Reporting from a video game industry in transition, 2003— 2011 by Carnegie Mellon University: ETC Press is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted. Copyright by ETC Press 2021 http://press.etc.cmu.edu/ ISBN: 9-781304-268426 (eBook) TEXT: The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NonDerivative 2.5 License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5/) IMAGES: The images of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NonDerivative 2.5 License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5/) Table of Contents Introduction COMMUNITY Infinite Princesses WebGame 2.0 @TopHatProfessor Layton and the Curious Twitter Accounts Madden in the Mist Pinball Wizards: A Visual Tour of the Pinball World Championships A Zombie of a Chance: LooKing BacK at the Left 4 Dead 2 Boycott The MaKing (and UnmaKing) of a Nintendo Fanboy Alone in the StreetPass Crowd CRAFT Steel Battalion and the Future of Direct-InVolVement Games A Horse of a Different Color Sympathy for the DeVil The Slow Death of the Game OVer The Game at the End of the Bar The World in a Chain Chomp Retro-Colored Glasses Do ArKham City’s Language Critics HaVe A Right To 'Bitch'? COMMERCE Hard DriVin’, Hard Bargainin’: InVestigating Midway’s ‘Ghost Racer’ Patent Indie Game Store Holiday Rush What If? MaKing a “Bundle” off of Indie Gaming Portal Goes Potato: How ValVe And Indie DeVs Built a Meta-Game Around Portal 2’s Launch Introduction As I write this introduction in 2021, we’re just about a year away from the 50th anniVersary of Pong, the first commercially successful video game and probably the simplest point to mark the start of what we now consider “the video game industry.” That makes video games one of the newest distinct artistic mediums out there, but not exactly new anymore. -

Gerold L. Schiebler, MD

ORAL HISTORY PROJECT Gerold L. Schiebler, MD Interviewed by Howard A. Pearson, MD March 18, 2000 Amelia Island, Florida This interview was supported by a donation from: The Florida Chapter of the American Academy of Pediatrics/Florida Pediatric Society https://www.aap.org/pediatrichistorycenter ã2001 American Academy of Pediatrics Elk Grove Village, IL Gerold L. Schiebler, MD Interviewed by Howard A. Pearson, MD Preface i About the Interviewer ii Interview of Gerold L. Schiebler, MD 1 Index of Interview 86 Curriculum Vita, Gerold L. Schiebler, MD 90 PREFACE Oral history has its roots in the sharing of stories which has occurred throughout the centuries. It is a primary source of historical data, gathering information from living individuals via recorded interviews. Outstanding pediatricians and other leaders in child health care are being interviewed as part of the Oral History Project at the Pediatric History Center of the American Academy of Pediatrics. Under the direction of the Historical Archives Advisory Committee, its purpose is to record and preserve the recollections of those who have made important contributions to the advancement of the health care of children through the collection of spoken memories and personal narrations. This volume is the written record of one oral history interview. The reader is reminded that this is a verbatim transcript of spoken rather than written prose. It is intended to supplement other available sources of information about the individuals, organizations, institutions, and events which are discussed. The use of face-to-face interviews provides a unique opportunity to capture a firsthand, eyewitness account of events in an interactive session. -

A Wonderful Answer

A WONDERFUL ANSWER BOB DYLAN 2016 by Olof Björner A SUMMARY OF RECORDING & CONCERT ACTIVITIES, NEW RELEASES, EXHIBITIONS & BOOKS. © 2017 by Olof Björner All Rights Reserved. This text may be reproduced, re-transmitted, redistributed and otherwise propagated at will, provided that this notice remains intact and in place. A Wonderful Answer — Bob Dylan 2016 page 2 of 42 1 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................. 4 2 2016 AT A GLANCE ......................................................................................................................... 4 3 THE 2016 CALENDAR ..................................................................................................................... 5 4 NEW RELEASES ............................................................................................................................... 6 4.1 Fallen Angels ................................................................................................................................ 6 4.2 The 1966 Live Recordings ........................................................................................................... 6 4.2.1 Background ........................................................................................................................... 6 4.2.2 CDs........................................................................................................................................ 7 5 THE NOBEL PRIZE ......................................................................................................................... -

Configuration of Application Permissions with Contextual Access Control

CONFIGURATION OF APPLICATION PERMISSIONS WITH CONTEXTUAL ACCESS CONTROL by Andrew Besmer A dissertation submitted to the faculty of The University of North Carolina at Charlotte in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Information Technology Charlotte 2013 Approved by: Dr. Heather Richter Lipford Dr. Mohamed Shehab Dr. Celine Latulipe Dr. Richard Lambert Dr. Lorrie Cranor ii c 2013 Andrew Besmer ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii ABSTRACT ANDREW BESMER. Configuration of application permissions with contextual access control. (Under the direction of DR. HEATHER RICHTER LIPFORD) Users are burdened with the task of configuring access control policies on many dif- ferent application platforms used by mobile devices and social network sites. Many of these platforms employ access control mechanisms to configure application per- missions before the application is first used and provide an all or nothing decision for the user. When application platforms provide fine grained control over decision making, many users exhibit behavior that indicates they desire more control over their application permissions. However, users who desire control over application permissions still struggle to properly configure them because they lack the context in which to make better decisions. In this dissertation, I attempt to address these problems by exploring decision making during the context of using mobile and social network applications. I hypothesize that users are able to better configure access control permissions as they interact with applications by supplying more contextual information than is available when the application is being installed. I also explore how logged access data generated by the application platform can provide users with more understanding of when their data is accessed. -

(In)Equality on Reddit

DICTATING THE TERMS: GAMERGATE, DEMOCRACY, AND (IN)EQUALITY ON REDDIT Shane Michael Snyder A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2019 Committee: Radhika Gajjala, Committee Chair Laura Landry-Meyer Graduate Faculty Representative Sandra Faulkner Timothy Messer-Kruse © 2019 Shane Snyder All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Radhika Gajjala, Committee Chair In late 2014 the mainstream press reported about a far-right movement that sought to discredit feminist, anti-racist, and trans-inclusive interventions in the video games industry, its products, and its consumer culture. Called GamerGate by its devotees, the movement began when American game designer Zoë Quinn weathered public harassment after her ex-boyfriend published a five-part essay falsely alleging she had sex with a game journalist to collect a positive review for her game Depression Quest. GamerGate activists launched a smear campaign against Quinn but attempted to absolve themselves of harassment by rebranding the movement as a game consumer revolt against unethical journalists and leftist academics. Almost five years later, GamerGate continues to grow in membership on its official subreddit, /r/KotakuInAction, which is a self-governed community hosted on the popular discussion forum-based social media platform Reddit. Shortly after /r/KotakuInAction materialized, a conscientious objector created the pro-feminist /r/GamerGhazi to resist GamerGate. Despite Reddit’s massive user base, its 1.2 million subreddits, and its ubiquity in American culture, it remains an underexplored space in the academic literature. Academics have neither adequately addressed Reddit’s role in promoting far-right communities like /r/KotakuInAction, nor the efficacy of using Reddit as a space for staging feminist resistance to such communities. -

H2O Environmental, Inc. V. Farm Supply Distributors, Inc. Clerk's Record Dckt

UIdaho Law Digital Commons @ UIdaho Law Idaho Supreme Court Records & Briefs, All Idaho Supreme Court Records & Briefs 7-11-2017 H2O Environmental, Inc. v. Farm Supply Distributors, Inc. Clerk's Record Dckt. 45116 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.uidaho.edu/ idaho_supreme_court_record_briefs Recommended Citation "H2O Environmental, Inc. v. Farm Supply Distributors, Inc. Clerk's Record Dckt. 45116" (2017). Idaho Supreme Court Records & Briefs, All. 7157. https://digitalcommons.law.uidaho.edu/idaho_supreme_court_record_briefs/7157 This Court Document is brought to you for free and open access by the Idaho Supreme Court Records & Briefs at Digital Commons @ UIdaho Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Idaho Supreme Court Records & Briefs, All by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ UIdaho Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF IDAHO H2O ENVIRONMENTAL, INC., an Idaho corporation, Supreme Court Case No. 45116 Plaintiff-Appellant, vs. FARM SUPPLY DISTRIBUTORS, INC., an Oregon corporation, Defendant-Respondent. CLERK'S RECORD ON APPEAL Appeal from the District Court of the Fourth Judicial District, in and for the County of Ada. HONORABLE GERALD F. SCHROEDER VAUGHN FISHER HANS A. MITCHELL ATTORNEY FOR APPELLANT ATTORNEY FOR RESPONDENT BOISE, IDAHO BOISE, IDAHO 000001 ADA COUNTY DISTRICT COURT CASE SUMMARY CASE No. CV-OC-2015-236 H2O Environmental Inc § Location: Ada County District Court vs. § Judicial Officer: Schroeder, Gerald F. Farm Supply Distributors Inc § Filed on: 01/08/2015 § Case Number History: CASE INFORMATION AA- All Initial District Court Case Type: Filings (Not E, F, and Hl) DATE CASE ASSIGNMENT Current Case Assignment Case Number CV-OC-2015-236 Court Ada County District Court Date Assigned 08/02/2016 Judicial Officer Schroeder, Gerald F.