Reporting from a Video Game Industry in Transition, 2003 – 2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Atom Smashersrel

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT Voleine Amilcar, ITVS 415-356-8383 x 244 [email protected] Mary Lugo 770-623-8190 [email protected] Cara White 843-881-1480 [email protected] For downloadable images, visit itvs.org/pressroom/photos/ For the program companion website, visit pbs.org/independentlens/atomsmashers “THE ATOM SMASHERS,” AN EXCITING INSIDE LOOK AT THE FRONTIER OF SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH, TO HAVE ITS BROADCAST PREMIERE ON THE EMMY ® AWARD–WINNING PBS SERIES INDEPENDENT LENS ON TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 25, AT 10 PM “Finding this Higgs particle will help scientists figure out why the universe is made of something instead of nothing, why there are atoms, people, planets, stars and galaxies. But it also will do much more than that. It will open a door to a hidden world of physics, where scientists hope to find unimagined wonders that will make relativity and quantum mechanics seem like Tinker Toys.” —Ronald Kotulak, Chicago Tribune (San Francisco, CA)—Physicists at Fermilab, the world’s most powerful particle accelerator laboratory, are closing in on one of the universe’s best-kept secrets, the Holy Grail of physics: why everything has mass. With the Tevatron, an underground particle accelerator buried deep beneath the Illinois prairie, Fermilab scientists smash matter together, accelerating protons and antiprotons in a four-mile-long ring at nearly the speed of light, to find a particle—the Higgs boson—whose existence was theorized nearly 40 years ago by Scottish scientist Peter Higgs. The physicists searching for the Higgs boson are excited; they may be approaching the discovery of a lifetime, and there’s almost certainly a Nobel Prize for whoever finally finds it. -

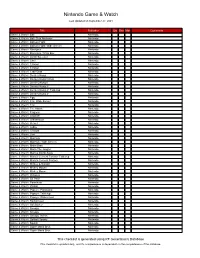

Nintendo Game & Watch

Nintendo Game & Watch Last Updated on September 27, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments Game & Watch: Ball Nintendo Game & Watch: Ball: Club Nintendo Nintendo Game & Watch: Balloon Fight Nintendo Game & Watch: Balloon Fight: Wide Screen Nintendo Game & Watch: Blackjack Nintendo Game & Watch: Blackjack: White Box Nintendo Game & Watch: Bomb Sweeper Nintendo Game & Watch: Chef Nintendo Game & Watch: Climber Nintendo Game & Watch: Climber Nintendo Game & Watch: Crab Grab Nintendo Game & Watch: Donkey Kong Nintendo Game & Watch: Donkey Kong Circus Nintendo Game & Watch: Donkey Kong II Nintendo Game & Watch: Donkey Kong Jr Nintendo Game & Watch: Donkey Kong Jr: Tabletop Nintendo Game & Watch: Donkey Kong Jr Nintendo Game & Watch: Egg Nintendo Game & Watch: Fire: Wide Screen Nintendo Game & Watch: Fire Nintendo Game & Watch: Fire Attack Nintendo Game & Watch: Flagman Nintendo Game & Watch: Goldcliff Nintendo Game & Watch: Greenhouse Nintendo Game & Watch: Helmet Nintendo Game & Watch: Judge Nintendo Game & Watch: Lifeboat Nintendo Game & Watch: Lion Nintendo Game & Watch: Manhole Nintendo Game & Watch: Manhole: Wide Screen Nintendo Game & Watch: Mario Bros Nintendo Game & Watch: Mario The Juggler Nintendo Game & Watch: Mario's Bomb Away Nintendo Game & Watch: Mario's Cement Factory: Tabletop Nintendo Game & Watch: Mario's Cement Factory Nintendo Game & Watch: Mickey & Donald Nintendo Game & Watch: Mickey Mouse Nintendo Game & Watch: Mickey Mouse Nintendo Game & Watch: Octopus Nintendo Game & Watch: Oil Panic Nintendo Game & Watch: Parachute Nintendo Game & Watch: Pinball Nintendo Game & Watch: Popeye: Panorama Nintendo Game & Watch: Popeye: Tabletop Nintendo Game & Watch: Popeye: Widescreen Nintendo Game & Watch: Rainshower Nintendo Game & Watch: Safebuster Nintendo Game & Watch: Snoopy Nintendo Game & Watch: Snoopy Nintendo Game & Watch: Snoopy Tennis Nintendo Game & Watch: Spitball Sparky Nintendo Game & Watch: Squish Nintendo Game & Watch: Super Mario Bros. -

Super Mario 64 (And Also Super Mario 64 DS) Jumpchain by Cthulhu Fartagn Intro

Super Mario 64 (And also Super Mario 64 DS) Jumpchain by Cthulhu Fartagn Intro Once again, Princess Peach and her kingdom are under attack by the evil King Bowser Koopa and his Koopa Troopa. This time, Bowser has decided not to drag her off to parts unknown (read as, the Bowser Kingdom) and has instead utilized some magical paint to seal away anyone and anything that would resist him inside paintings and portraits that he has created. You - or rather, Mario, though you can always help him - will need to enter these paintings to steal back the stars that empower them, and by extension, Bowser himself. If this takes you the ten years that you’ll be staying here, I’d be very surprised. Of course, you may not be here to help. You might be one of the many minor nobles or lesser rulers, one that has found aiding Bowser to be advantageous. Just keep in mind that if you do help, there will be cake. Either way, go ahead and take these. +1000 cp Origins Plumber You’ve been invited to the princesses castle, though by the time you reach it Bowser will have pulled yet another zany stunt and it’ll be time to get to work. Best put on your best overalls and cap, because it’s time to flush the turd. As a Plumber, you are a human, or possibly one of the species that are a remarkably similar lookalike to them. Helper Help Princess Peach, or help Bowser? Peach… or Bowser. That’s the choice you have to make right now. -

2K and Bethesda Softworks Release Legendary Bundles February 11

2K and Bethesda Softworks Release Legendary Bundles February 11, 2014 8:00 AM ET The Elder Scrolls® V: Skyrim and BioShock® Infinite; Borderlands® 2 and Dishonored™ bundles deliver supreme quality at an unprecedented price NEW YORK--(BUSINESS WIRE)--Feb. 11, 2014-- 2K and Bethesda Softworks® today announced that four of the most critically-acclaimed video games of their generation – The Elder Scrolls® V: Skyrim, BioShock® Infinite, Borderlands® 2, and Dishonored™ – are now available in two all-new bundles* for $29.99 each in North America on the Xbox 360 games and entertainment system from Microsoft, PlayStation®3 computer entertainment system, and Windows PC. ● The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim & BioShock Infinite Bundle combines two blockbusters from world-renowned developers Bethesda Game Studios and Irrational Games. ● The Borderlands 2 & Dishonored Bundle combines Gearbox Software’s fan favorite shooter-looter with Arkane Studio’s first- person action breakout hit. Critics agree that Skyrim, BioShock Infinite, Borderlands 2, and Dishonored are four of the most celebrated and influential games of all time. 2K and Bethesda Softworks(R) today announced that four of the most critically- ● Skyrim garnered more than 50 perfect review acclaimed video games of their generation - The Elder Scrolls(R) V: Skyrim, scores and more than 200 awards on its way BioShock(R) Infinite, Borderlands(R) 2, and Dishonored(TM) - are now available to a 94 overall rating**, earning praise from in two all-new bundles* for $29.99 each in North America on the Xbox 360 some of the industry’s most influential and games and entertainment system from Microsoft, PlayStation(R)3 computer respected critics. -

Re-Writing the Script : Representations of Transgender Creativity In

Kate Norbury Re-writing the Script: Representations of Transgender Creativity in Contemporary Young Adult Fiction and Television Abstract: The transgender, gender-atypical or intersex protagonist challeng- es normative assumptions and expectations about gender, identity and sexu- ality. This article argues that contemporary transgender-themed young adult fiction and television uses the theme of creativity or the creative achievement script to override previously negative representations of adolescent transgender subjectivities. I consider three English-language novels and one television series for young adults and use script theory to analyse these four texts. Cris Beam’s I Am J (2011) and Kirstin Cronn-Mills’ Beautiful Music for Ugly Children (2012), both originally published in the United States, depict female to male transitions. Alyssa Brugman’s Alex As Well (2013), originally published in Australia, foregrounds the experience of an inter- sex teenager, Alex, raised as a boy, but who, at the age of fourteen, decides she is female. Glee introduced the transgender character Unique in 2012, and in 2014 she continued to be a central member of the New Directions choir. The Swedish graphic novel, Elias Ericson’s Åror (Oars, 2013), includes two transgender characters who enact the creative achievement script and fall in love with each other. Ericson’s graphic novel goes further than the English-language texts to date. Collectively, these transgender, gender-atypical or intersex protagonists and central characters assert their creativity and individual agency. The transgender character’s particular cre- ativity ultimately secures a positive sense of self. This more recent selection of texts which date from 2011 validate young adult transgender experience and model diversity and acceptance. -

Sunday Morning Grid 12/28/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 12/28/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Chargers at Kansas City Chiefs. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News 1st Look Paid Premier League Goal Zone (N) (TVG) World/Adventure Sports 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Outback Explore St. Jude Hospital College 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Philadelphia Eagles at New York Giants. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Black Knight ›› (2001) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Simply Ming Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Play. Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Ed Slott’s Retirement Rescue for 2014! (TVG) Å BrainChange-Perlmutter 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) República Deportiva (TVG) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Tu Dia Tu Dia Happy Feet ››› (2006) Elijah Wood. -

Bulletstorm-Manuals

WARNING: PHOTOSENSITIVITY/ CONTENTS EPILEPSY/SEIZURES A very small percentage of individuals may experience epileptic seizures or blackouts when exposed to certain light patterns or flashing lights. Exposure to certain patterns or backgrounds on a television screen or when 1 CONTROLLING 9 MAIN MENU playing video games may trigger epileptic seizures or blackouts in these individuals. These conditions may GRAYSON HUNT 10 PLAY ONLINE trigger previously undetected epileptic symptoms or seizures in persons who have no history of prior seizures 2 GETTING STARTED 13 LIMITED 90-DAY or epilepsy. If you, or anyone in your family, has an epileptic condition or has had seizures of any kind, consult your physician before playing. IMMEDIATELY DISCONTINUE use and consult your physician before resuming 3 PLAYING THE GAME WARRANTY gameplay if you or your child experience any of the following health problems or symptoms: dizziness eye or muscle twitches disorientation any involuntary movement altered vision loss of awareness seizures or convulsion. This product has been rated by the Entertainment Software Rating Board. For information about the ESRB rating RESUME GAMEPLAY ONLY ON APPROVAL OF YOUR PHYSICIAN. please visit www.esrb.org. USE AND HANDLING OF VIDEO GAMES TO REDUCE THE LIKELIHOOD OF A SEIZURE Use in a well-lit area and keep as far away as possible from the television screen. CONTROLLING GRAYSON HUNT Avoid large screen televisions. Use the smallest television screen available. Avoid prolonged use of the PlayStation®3 system. Take a 15-minute break during each hour of play. PLAYER CONTROLS Avoid playing when you are tired or need sleep. Move left stick Stop using the system immediately if you experience any of the following symptoms: lightheadedness, nausea, Look right stick or a sensation similar to motion sickness; discomfort or pain in the eyes, ears, hands, arms, or any other part of Crouch B button the body. -

Exploring the Experiences of Gamers Playing As Multiple First-Person Video Game Protagonists in Halo 3: ODST’S Single-Player Narrative

Exploring the experiences of gamers playing as multiple first-person video game protagonists in Halo 3: ODST’s single-player narrative Richard Alexander Meyers Bachelor of Arts Submitted in fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts (Research) School of Creative Practice Creative Industries Faculty Queensland University of Technology 2018 Keywords First-Person Shooter (FPS), Halo 3: ODST, Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis (IPA), ludus, paidia, phenomenology, video games. i Abstract This thesis explores the experiences of gamers playing as multiple first-person video game protagonists in Halo 3: ODST, with a view to formulating an understanding of player experience for the benefit of video game theorists and industry developers. A significant number of contemporary console-based video games are coming to be characterised by multiple playable characters within a game’s narrative. The experience of playing as more than one video game character in a single narrative has been identified as an under-explored area in the academic literature to date. An empirical research study was conducted to explore the experiences of a small group of gamers playing through Halo 3: ODST’s single-player narrative. Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) was used as a methodology particularly suited to exploring a new or unexplored area of research and one which provides a nuanced understanding of a small number of people experiencing a phenomenon such as, in this case, playing a video game. Data were gathered from three participants through experience journals and subsequently through two semi- structured interviews. The findings in relation to participants’ experiences of Halo 3: ODST’s narrative were able to be categorised into three interrelated narrative elements: visual imagery and world-building, sound and music, and character. -

Playvs Announces $30.5M Series B Led by Elysian Park

PLAYVS ANNOUNCES $30.5M SERIES B LED BY ELYSIAN PARK VENTURES, INVESTMENT ARM OF THE LA DODGERS, ADDITIONAL GAME TITLES AND STATE EXPANSIONS FOR INAUGURAL SEASON FEBRUARY 2019 High school esports market leader introduces Rocket League and SMITE to game lineup adds associations within Alabama, Mississippi, and Texas to sanctioned states for Season One and closes a historic round of funding from Diddy, Adidas, Samsung and others EMBARGOED FOR NOVEMBER 20TH AT 10AM EST / 7AM PST LOS ANGELES, CA - November 20th - PlayVS – the startup building the infrastructure and official platform for high school esports - today announced its Series B funding of $30.5 million led by Elysian Park Ventures, the private investment arm of the Los Angeles Dodgers ownership group, with five existing investors doubling down, New Enterprise Associates, Science Inc., Crosscut Ventures, Coatue Management and WndrCo, and new groups Adidas (marking the company’s first esports investment), Samsung NEXT, Plexo Capital, along with angels Sean “Diddy” Combs, David Drummond (early employee at Google and now SVP Corp Dev at Alphabet), Rahul Mehta (Partner at DST Global), Rich Dennis (Founder of Shea Moisture), Michael Dubin (Founder and CEO of Dollar Shave Club), Nat Turner (Founder and CEO of Flatiron Health) and Johnny Hou (Founder and CEO of NZXT). This milestone round comes just five months after PlayVS’ historic $15M Series A funding. “We strive to be at the forefront of innovation in sports, and have been carefully -

Trinity Support Asked for WSSF to Help Needy Students Abroad

TRI , , ft t Volume XLV HARTFORD, CONN., DECEMBER 17, 1947 Number 10 Trinity Support Asked for WSSF Boosters Club to Trinity Basketeers Overwhelm Sponsor Pre-Xmas To Help Needy Students Abroad Williams in Home Debut, 58-36 I Dance This Evening Kitchen Describes Large Crowd Expected I I Ron Watson High Scorer Conditions; Drive Debaters Defeat At Festivities; Pipes Stassen Interviewed As Ephmen Succumb I Begins in January Haverford in Octet to Entertain By "Tdpod" Reporter At State Armory Speaking in Wednesday's Chapel This evening at 8:30 an informal By Bill Wetter service, Mr. Wilmer J. Kitchen asked Opening Battle pre-Christmas dance will be held in At Yale Meeting 1 I Trinity's support in a drive to give Cook Lounge and Hamlin Dining Hall An estimated crowd of 1600 watched Taking the negative side of the On Monday afternoon, December 8, 400,000 students abroad direly needed to help get the vacation off to a flying Trinity bounce back from its defeat question "Should the United States food, clothes, shelter, and hospitaliza start. The dance will be sponsored by about one hundred collegiate and pro- by M.I.T. earlier in the week, to romp Adopt Universal Military Training?", tion. Mr. Kitchen, Executive Secre the increasingly active Boosters Club. fessional newspaper reporters gath over the Ephmen of Williams to the I the Trinity debating team of David tary of the Wedel Student Service Music will be by Ed Lally, his piano e1·ed at the "Yale Daily News" build tune of 58 to 36, at the State Armory Rivkin and Samuel Goldstein opened Fund, said that due to crop failures and his orchestra, and refreshments last Saturday night. -

List of Turbografx16 Games

List of TurboGrafx16 Games 1) 1941: Counter Attack 28) Blodia 2) 1943: Kai 29) Bloody Wolf 3) 21-Emon 30) Body Conquest II ~The Messiah~ 4) Adventure Island 31) Bomberman 5) Aero Blasters 32) Bomberman '93 6) After Burner II 33) Bomberman '93 Special 7) Air Zonk 34) Bomberman '94 8) Aldynes: The Mission Code for Rage Crisis 35) Bomberman: Users Battle 9) Alice in Wonderdream 36) Bonk 3: Bonk's Big Adventure 10) Alien Crush 37) Bonk's Adventure 11) Andre Panza Kick Boxing 38) Bonk's Revenge 12) Ankoku Densetsu 39) Bouken Danshaku Don: The Lost Sunheart 13) Aoi Blink 40) Boxyboy 14) Appare! Gateball 41) Bravoman 15) Artist Tool 42) Break In 16) Atomic Robo-Kid Special 43) Bubblegum Crash!: Knight Sabers 2034 17) Ballistix 44) Bull Fight: Ring no Haja 18) Bari Bari Densetsu 45) Burning Angels 19) Barunba 46) Cadash 20) Batman 47) Champion Wrestler 21) Battle Ace 48) Champions Forever Boxing 22) Battle Lode Runner 49) Chase H.Q. 23) Battle Royale 50) Chew Man Fu 24) Be Ball 51) China Warrior 25) Benkei Gaiden 52) Chozetsu Rinjin Berabo Man 26) Bikkuri Man World 53) Circus Lido 27) Blazing Lazers 54) City Hunter 55) Columns 84) Dragon's Curse 56) Coryoon 85) Drop Off 57) Cratermaze 86) Drop Rock Hora Hora 58) Cross Wiber: Cyber-Combat-Police 87) Dungeon Explorer 59) Cyber Cross 88) Dungeons & Dragons: Order of the Griffon 60) Cyber Dodge 89) Energy 61) Cyber Knight 90) F1 CIRCUS 62) Cyber-Core 91) F1 Circus '91 63) DOWNLOAD 92) F1 Circus '92 64) Daichikun Crisis: Do Natural 93) F1 Dream 65) Daisenpuu 94) F1 Pilot 66) Darius Alpha 95) F1 Triple -

View List of Games Here

Game List SUPER MARIO BROS MARIO 14 SUPER MARIO BROS3 DR MARIO MARIO BROS TURTLE1 TURTLE FIGHTER CONTRA 24IN1 CONTRA FORCE SUPER CONTRA 7 KAGE JACKAL RUSH N ATTACK ADVENTURE ISLAND ADVENTURE ISLAND2 CHIP DALE1 CHIP DALE3 BUBBLE BOBBLE PART2 SNOW BROS MITSUME GA TOORU NINJA GAIDEN2 DOUBLE DRAGON2 DOUBLE DRAGON3 HOT BLOOD HIGH SCHOOL HOT BLOOD WRESTLE ROBOCOP MORTAL KOMBAT IV SPIDER MAN 10 YARD FIGHT TANK A1990 THE LEGEND OF KAGE ALADDIN3 ANTARCTIC ADVENTURE ARABIAN BALLOON FIGHT BASE BALL BINARY LAND BIRD WEEK BOMBER MAN BOMB SWEEPER BRUSH ROLLER BURGER TIME CHAKN POP CHESS CIRCUS CHARLIE CLU CLU LAND FIELD COMBAT DEFENDER DEVIL WORLD DIG DUG DONKEY KONG DONKEY KONG JR DONKEY KONG3 DONKEY KONG JR MATH DOOR DOOR EXCITEBIKE EXERION F1 RACE FORMATION Z FRONT LINE GALAGA GALAXIAN GOLF RAIDON BUNGELING BAY HYPER OLYMPIC HYPER SPORTS ICE CLIMBER JOUST KARATEKA LODE RUNNER LUNAR BALL MACROSS JEWELRY 4 MAHJONG MAHJONG MAPPY NUTS MILK MILLIPEDE MUSCLE NAITOU9 DAN SHOUGI H NIBBLES NINJA 1 NINJA3 ROAD FIGHTER OTHELLO PAC MAN PINBALL POOYAN POPEYE SKY DESTROYER Space ET STAR FORCE STAR GATE TENNIS URBAN CHAMPION WARPMAN YIE AR KUNG FU ZIPPY RACE WAREHOUSE BOY 1942 ARKANOID ASTRO ROBO SASA B WINGS BADMINGTON BALTRON BOKOSUKA WARS MIGHTY BOMB JACK PORTER CHUBBY CHERUB DESTROYI GIG DUG2 DOUGH BOY DRAGON TOWER OF DRUAGA DUCK ELEVATOR ACTION EXED EXES FLAPPY FRUITDISH GALG GEIMOS GYRODINE HEXA ICE HOCKEY LOT LOT MAGMAX PIKA CHU NINJA 2 QBAKE ONYANKO TOWN PAC LAND PACHI COM PRO WRESTLING PYRAMID ROUTE16 TURBO SEICROSS SLALOM SOCCER SON SON SPARTAN X SPELUNKER