Exploring the Experiences of Gamers Playing As Multiple First-Person Video Game Protagonists in Halo 3: ODST’S Single-Player Narrative

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chell Game: Representation, Identification, and Racial Ambiguity in PORTAL and PORTAL 2 2015

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Jennifer deWinter; Carly A. Kocurek Chell Game: Representation, Identification, and Racial Ambiguity in PORTAL and PORTAL 2 2015 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/14996 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Sammelbandbeitrag / collection article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: deWinter, Jennifer; Kocurek, Carly A.: Chell Game: Representation, Identification, and Racial Ambiguity in PORTAL and PORTAL 2. In: Thomas Hensel, Britta Neitzel, Rolf F. Nohr (Hg.): »The cake is a lie!« Polyperspektivische Betrachtungen des Computerspiels am Beispiel von PORTAL. Münster: LIT 2015, S. 31– 48. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/14996. Erstmalig hier erschienen / Initial publication here: http://nuetzliche-bilder.de/bilder/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Hensel_Neitzel_Nohr_Portal_Onlienausgabe.pdf Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Creative Commons - This document is made available under a creative commons - Namensnennung - Nicht kommerziell - Weitergabe unter Attribution - Non Commercial - Share Alike 3.0/ License. For more gleichen Bedingungen 3.0/ Lizenz zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere information see: Auskünfte zu dieser Lizenz finden Sie hier: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/ http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/ Jennifer deWinter / Carly A. Kocurek Chell Game: Representation, Identification, and Racial Ambiguity in ›Portal‹ and ›Portal 2‹ Chell stands in a corner facing a portal, then takes aim at the adjacent wall with the Aperture Science Handheld Portal Device. Between the two portals, one ringed in blue, one ringed in orange, Chell is revealed, reflected in both. And, so, we, the player, see Chell. She is a young woman with a ponytail, wearing an orange jumpsuit pulled down to her waist and an Aperture Science-branded white tank top. -

2K and Bethesda Softworks Release Legendary Bundles February 11

2K and Bethesda Softworks Release Legendary Bundles February 11, 2014 8:00 AM ET The Elder Scrolls® V: Skyrim and BioShock® Infinite; Borderlands® 2 and Dishonored™ bundles deliver supreme quality at an unprecedented price NEW YORK--(BUSINESS WIRE)--Feb. 11, 2014-- 2K and Bethesda Softworks® today announced that four of the most critically-acclaimed video games of their generation – The Elder Scrolls® V: Skyrim, BioShock® Infinite, Borderlands® 2, and Dishonored™ – are now available in two all-new bundles* for $29.99 each in North America on the Xbox 360 games and entertainment system from Microsoft, PlayStation®3 computer entertainment system, and Windows PC. ● The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim & BioShock Infinite Bundle combines two blockbusters from world-renowned developers Bethesda Game Studios and Irrational Games. ● The Borderlands 2 & Dishonored Bundle combines Gearbox Software’s fan favorite shooter-looter with Arkane Studio’s first- person action breakout hit. Critics agree that Skyrim, BioShock Infinite, Borderlands 2, and Dishonored are four of the most celebrated and influential games of all time. 2K and Bethesda Softworks(R) today announced that four of the most critically- ● Skyrim garnered more than 50 perfect review acclaimed video games of their generation - The Elder Scrolls(R) V: Skyrim, scores and more than 200 awards on its way BioShock(R) Infinite, Borderlands(R) 2, and Dishonored(TM) - are now available to a 94 overall rating**, earning praise from in two all-new bundles* for $29.99 each in North America on the Xbox 360 some of the industry’s most influential and games and entertainment system from Microsoft, PlayStation(R)3 computer respected critics. -

Motherhood: Designing Silent Player Characters for Storytelling

Motherhood: Designing Silent Player Characters for Storytelling Extended Abstract Bria Mears Jichen Zhu Drexel University Drexel University 3141 Chestnut St 3141 Chestnut St Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104 [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT a list of methods designers can use to eectively communicate a e silent player character (SPC) is a reoccurring but not well- SPC’s story. ird, we developed Motherhood, a short narrative understood type of player character in narrative-driven games. In experience featuring a SPC that exemplies how our found pat- this paper, we present how our ndings from an analysis of SPC terns can be implemented into a game’s design to communicate development have been exemplied in an interactive narrative a pre-dened SPC. Motherhood was built to evaluate the paerns experience. e ndings presented in this study were approved as developed in this study. a FDG’17 poster submission. First, we identify two main types of SPCs: projective and expressive characters. Second, we synthesized 2 RELATED WORK a list of methods designers can use to eectively communicate A traditional silent protagonist is oen linked with the term “avatar” a SPC’s story. ird, we present Motherhood, a short narrative - dened as “a player’s embodiment in the game” [2, 3]; in other experience featuring the development of a pre-dened SPC. words, the “blank canvas” PC. In the early days of digital games, CCS CONCEPTS game characters were lile more than generic gures that lacked both personality and depth in their design [9] and players played •So ware and its engineering ! Interactive games; •Applied through the game [1], focusing on their ludic goals, rather than computing ! Computer games; taking an interest in the avatar itself. -

Fighting Games, Performativity, and Social Game Play a Dissertation

The Art of War: Fighting Games, Performativity, and Social Game Play A dissertation presented to the faculty of the Scripps College of Communication of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Todd L. Harper November 2010 © 2010 Todd L. Harper. All Rights Reserved. This dissertation titled The Art of War: Fighting Games, Performativity, and Social Game Play by TODD L. HARPER has been approved for the School of Media Arts and Studies and the Scripps College of Communication by Mia L. Consalvo Associate Professor of Media Arts and Studies Gregory J. Shepherd Dean, Scripps College of Communication ii ABSTRACT HARPER, TODD L., Ph.D., November 2010, Mass Communications The Art of War: Fighting Games, Performativity, and Social Game Play (244 pp.) Director of Dissertation: Mia L. Consalvo This dissertation draws on feminist theory – specifically, performance and performativity – to explore how digital game players construct the game experience and social play. Scholarship in game studies has established the formal aspects of a game as being a combination of its rules and the fiction or narrative that contextualizes those rules. The question remains, how do the ways people play games influence what makes up a game, and how those players understand themselves as players and as social actors through the gaming experience? Taking a qualitative approach, this study explored players of fighting games: competitive games of one-on-one combat. Specifically, it combined observations at the Evolution fighting game tournament in July, 2009 and in-depth interviews with fighting game enthusiasts. In addition, three groups of college students with varying histories and experiences with games were observed playing both competitive and cooperative games together. -

Don't Forget to Save!

Don’t Forget to Save! The Impact of User Experience Design on Workflow of Authoring Video Game Narratives (Transfer Thesis) Daniel Green Department of Science and Technology Bournemouth University A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy November 2019 This page is intentionally left blank. This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author and due acknowledgement must always be made of the use of any material contained in, or derived from, this thesis. This page is intentionally left blank. Abstract Since their inception, video games have been a capable storytelling device. This is only amplified as technology improves. Contemporary video games boast awide range of interaction and presentational techniques that can enrich the narrative experience. Supporting authors with tools to prototype their stories, or even as direct integration into a game, is vital. This is especially important as the complexity and length of such narratives continues to increase. Designing these kinds of tools is no easy feat. In order to develop authoring systems for game developers that support prototyping or implementation of their envisioned narratives, we must gain an understanding of the underlying constituents that make up video game narrative and their structural and relational properties. Additionally, when designing the interface of and interactions with such systems, the User Experience (UX) design decisions taken may impact the workflow of the authors to implement their vision. Therefore, we must also gain an understanding of how various UX design paradigms alter the usability of our programs. -

Firewatch Download Torrent Mac the Forest Free Download Mac

firewatch download torrent mac The Forest Free Download Mac. Nov 23, 2020 — Into the Forest PC Game Walkthrough Free Download for Mac Full version highly compressed via direct link. Into the Forest PC Game Free …. Feb 1, 2007 — Download Forest Resort Mac for Mac to collect magic to restore the forest while attending to your customers.. May 4, 2019 — The Forest free download! Download here for free! Just download and play for PC! Cracked by CPY, CODEX and SKIDROW! Free Digital College Planner Printables + Stickers. I have been out of college for a few years now, but my little brother in law … forest app. forrest gump, forrest gump quotes, forrest fenn, forrest galante, forrest fenn treasure, forest, forest whitaker, forester, forrest, forestry, forest game, forest app, forest korean drama, forest cartoon, forest green, forest of dean. RevMan Web is the online platform recommended for Cochrane intervention and flexible reviews. Log in to RevMan Web to access your review. RevMan 5 is free … forest game. Forest is an app helping you stay away from your smartphone and stay focused on your work.. The Forest Free Download PC Game Latest Update DMG For Mac OS Android APK Free Download PC Games Highly Compressed Direct Download In Parts …. Download Forest for Mac – Stay focused on your work and avoid time wasting websites with the help of this cute extension that comes with support for Chrome … Firewatch PC Game Free Download. Dalam Firewatch, Anda akan memerankan seorang tokoh bernama Henry. Ketika sedang melakukan patroli di hutan, dirinya mendapati bahwa menara pengawas telah diobrak-abrik oleh orang lain. -

Digital Cultures

88888888888DIGITAL 88888888888CULTURES Understanding New Media 88888888888 Edited88888888888 by Glen Creeber and Royston88888888888 Martin Digital Cultures Digital Cultures Edited by Glen Creeber and Royston Martin Open University Press McGraw-Hill Education McGraw-Hill House Shoppenhangers Road Maidenhead Berkshire England SL6 2QL email: [email protected] world wide web: www.openup.co.uk and Two Penn Plaza, New York, NY 10121—2289, USA First published 2009 Copyright © Creeber and Martin 2009 All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher or a licence from the Copyright Licensing Agency Limited. Details of such licences (for reprographic reproduction) may be obtained from the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd of Saffron House, 6–10 Kirby Street, London, EC1N 8TS. A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library ISBN-13: 978-0-33-5221974 (pb) 978-0-33-5221981 (hb) ISBN-10: 0335221971 (pb) 033522198X (hb) Typeset by Kerrypress, Luton, Bedfordshire Printed and bound in the UK by Bell & Bain Ltd, Glasgow Fictitious names of companies, products, people, characters and/or data that may be used herein (in case studies or in examples) are not intended to represent any real individual, company, product or event. For Tomas Contents -

Music, Time and Technology in Bioshock Infinite 52 the Player May Get a Feeling That This Is Something She Does Frequently

The Music of Tomorrow, Yesterday! Music, Time and Technology in BioShock Infinite ANDRA IVĂNESCU, Anglia Ruskin University ABSTRACT Filmmakers such as Kenneth Anger, David Lynch and Quentin Tarantino have taken full advantage of the disconcerting effect that pop music can have on an audience. Recently, video games have followed their example, with franchises such as Grand Theft Auto, Fallout and BioShock using appropriated music as an almost integral part of their stories and player experiences. BioShock Infinite takes it one step further, weaving popular music of the past and pop music of the present into a compelling tale of time travel, multiverses, and free will. The third installment in the BioShock series has as its setting the floating city of Columbia. Decidedly steampunk, this vision of 1912 makes considerable use of popular music of the past alongside a small number of anachronistic covers of more modern pop music (largely from the 1980s) at crucial moments in the narrative. Music becomes an integral part of Columbia but also an integral part of the player experience. Although the soundscape matches the rest of the environment, the anachronistic covers seem to be directed at the player, the only one who would recognise them as out of place. The player is the time traveller here, even more so than the character they are playing, making BioShock Infinite one of the most literal representations of time travel and the tourist experience which video games can represent. KEYWORDS Video game music, film music, intertextuality, time travel. Introduction For every choice there is an echo. With each act we change the world […] If the world were reborn in your image, Would it be paradise or perdition? (BioShock 2 launch trailer, 2010) Elizabeth hugs a postcard of the Eiffel Tower. -

The Heroic Journey of a Villain

Háskóli Íslands Hugvísindasvið Enska The Heroic Journey of a Villain The Lost and Found Humanity of an Artificial Intelligence Ritgerð til MA-prófs í Ensku Ásta Karen Ólafsdóttir Kt.: 150390-2499 Leiðbeinandi: Guðrún B. Guðsteinsdóttir Maí 2017 Abstract In this essay, we will look at the villain of the Portal franchise, the artificial intelligence GLaDOS, in context with Maureen Murdock’s theory of the “Heroine’s Journey,” from her book The Heroine’s Journey: Woman’s Quest for Wholeness. The essay argues that although GLaDOS is not a heroine in the conventional sense, she is just as important of a figure in the franchise as its protagonist, Chell. GLaDOS acts both as the first game’s narrator and villain, as she runs the Aperture Science Enrichment Center where the games take place. Unlike Chell, GLaDOS is a speaking character with a complex backstory and goes through real character development as the franchise’s story progresses. The essay is divided into four chapters, a short history of women’s part as characters in video games, an introduction to Murdock’s “The Heroine’s Journey,” and its context to John Campbell’s “The Hero’s Journey,” a chapter on the Portal franchises, and then we go through “The Heroine’s Journey,” in regards to GLaDOS, and each step in its own subchapter. Our main focus will be on the second installment in the series, Portal 2. Since, in that game, GLaDOS goes through most of her heroine’s journey. In the first game, Portal, GLaDOS separates from her femininity and embraces the masculine, causing her fractured psyche, and as the player goes through Portal 2 along with her, she reclaims her femininity, finds her inner masculinity, and regains wholeness. -

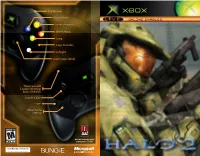

Score Pause Game Settings Fire Weapon Reload/Action Switch Weapo

Fire Weapon Reload/Action ONLINE ENABLED Switch Weapons Melee Attack Jump Swap Grenades Flashlight Zoom Scope (Click) Throw Grenade E-brake (Warthog) Boost (Vehicles) Crouch (Click) Score Pause Game Settings Get the strategy guide primagames.com® ® 0904 Part No. X10-96235 SAFETY INFORMATION TABLE OF CONTENTS About Photosensitive Seizures Secret Transmission ........................................................................................... 2 A very small percentage of people may experience a seizure when exposed to certain visual images, including flashing lights or patterns that may appear in video games. Even people who Master Chief .......................................................................................................... 3 have no history of seizures or epilepsy may have an undiagnosed condition that can cause these Breakdown of Known Covenant Units ......................................................... 4 “photosensitive epileptic seizures” while watching video games. These seizures may have a variety of symptoms, including lightheadedness, altered vision, eye or Controller ............................................................................................................... 6 face twitching, jerking or shaking of arms or legs, disorientation, confusion, or momentary loss of awareness. Seizures may also cause loss of consciousness or convulsions that can lead to injury from Mjolnir Mark VI Battle Suit HUD ..................................................................... 8 falling down or striking -

Halo Legendary Edition Overview of Components Cont

2-5 AGES 10+ PLAYERS RISK: HALO LEGENDARY EDITION OVERVIEW OF COMPONENTS CONT. “In a distant corner of the galaxy a new Halo ring, one of the ancient superweapons of the mysterious Forerunner civilization is found and the battle sparks anew: Brave Humanity, battling for survival and DICE discovery against the discipline and zealotry of the Covenant alliance of alien species who worship the long-absent Forerunners...and looming terrifying above both of these factions is the parasitic You use the dice when attacking and defending territories. Flood infection which threatens to corrupt all living creatures into mindless creatures of violence ( see ATTACKING, pg.10) and rage. Which faction will triumph in this legendary new front in the battle for the Halo universe? ATTACK DICE DEFENSE DICE That, players, is up to you...” MOBILE TELEPORTERS Pairs of Mobile Teleporters will be placed on the board onto different OVERVIEW OF COMPONENTS territories. These connect two previously separated territories. Forces can maneuver and attack normally via these Mobile Teleporters. (see USING Mobile Teleporters, pg. 8 for further explanation) WHAT’S INSIDE UNITS CONTENTS Every player will control a faction of one color. • 4 Battlefields • 2 UNSC Factions* • 22 Campaign cards Heroes • 2 Double-sided Game Boards • 2 COVENANT Factions** • 44 Faction cards Heroes possess elite skills in both attack • 10 Mobile Teleporters • 1 FLOOD Faction*** • 5 Bases and defense that can turn the tide of battle. • 5 Dice *UNSC - 1 spartan, 1 firebase, 36 marines, 18 tanks ( see ATTACKING, pg. 10 for further explanation) **Covenant - 1 aribiter, 1 command center, 36 grunts, 18 wraiths UNSC COVENANT FLOOD ***Flood - 1 thasher, 1 proto-gravemind, 36 infection forms and 18 carrier forms Not all components are used in every game mode. -

The Impact of Video Game Interactivity on the Narrative

THE IMPACT OF VIDEO GAME INTERACTIVITY ON THE NARRATIVE CAMERON EDMOND (BA) MACQUARIE UNIVERSITY FACULTY OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH OCTOBER 2015 This thesis is presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Research at Macquarie University. I certify that this thesis is entirely my own work and that I have given fully documented reference to the work of others. The thesis has not previously, in part or in whole, been submitted for assessment in any formal course of study. Signed: (Cameron Edmond) Contents Summary...................................................................................................................................7 Acknowledgements...................................................................................................................9 Introduction............................................................................................................................11 Chapter 1 – The Player-Hero: A Hollow Sphere................................................................25 Chapter 2 – The NPC Goddess: A Bridge Between Spheres..............................................43 Chapter 3 – The Game World: The Ultimate Controller of Interactivity........................59 Conclusion...............................................................................................................................75 Works Cited............................................................................................................................79 Appendix…….........................................................................................................................87