Review Essay

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Psychological Arguments for Free Will DISSERTATION Presented In

Psychological Arguments for Free Will DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Andrew Kissel Graduate Program in Philosophy The Ohio State University 2017 Dissertation Committee: Richard Samuels, Advisor Declan Smithies Abraham Roth Copyrighted by Andrew Kissel 2017 Abstract It is a widespread platitude among many philosophers that, regardless of whether we actually have free will, it certainly appears to us that we are free. Among libertarian philosophers, this platitude is sometimes deployed in the context of psychological arguments for free will. These arguments are united under the idea that widespread claims of the form, “It appears to me that I am free,” on some understanding of appears, justify thinking that we are probably free in the libertarian sense. According to these kinds of arguments, the existence of free will is supposed to, in some sense, “fall out” of widely accessible psychological states. While there is a long history of thinking that widespread psychological states support libertarianism, the arguments are often lurking in the background rather than presented at face value. This dissertation consists of three free-standing papers, each of which is motivated by taking seriously psychological arguments for free will. The dissertation opens with an introduction that presents a framework for mapping extant psychological arguments for free will. In the first paper, I argue that psychological arguments relying on widespread belief in free will, combined with doxastic conservative principles, are likely to fail. In the second paper, I argue that psychological arguments involving an inference to the best explanation of widespread appearances of freedom put pressure on non-libertarians to provide an adequate alternative explanation. -

Free Will and Determinism Debate on the Philosophy Forum

Free Will and Determinism debate on the Philosophy Forum. 6/2004 All posts by John Donovan unless noted otherwise. The following link is an interesting and enjoyable interview with Daniel Dennett discussing the ideas in his latest book where he describes how "free will" in humans and physical "determinism" are entirely compatible notions if one goes beyond the traditional philosophical arguments and examines these issues from an evolutionary viewpoint. http://www.reason.com/0305/fe.rb.pulling.shtml A short excerpt: Reason: A response might be that you’re just positing a more complicated form of determinism. A bird may be more "determined" than we are, but we nevertheless are determined. Dennett: So what? Determinism is not a problem. What you want is freedom, and freedom and determinism are entirely compatible. In fact, we have more freedom if determinism is true than if it isn’t. Reason: Why? Dennett: Because if determinism is true, then there’s less randomness. There’s less unpredictability. To have freedom, you need the capacity to make reliable judgments about what’s going to happen next, so you can base your action on it. Imagine that you’ve got to cross a field and there’s lightning about. If it’s deterministic, then there’s some hope of knowing when the lightning’s going to strike. You can get information in advance, and then you can time your run. That’s much better than having to rely on a completely random process. If it’s random, you’re at the mercy of it. A more telling example is when people worry about genetic determinism, which they completely don’t understand. -

Where's the Action? Epiphenomenalism and the Problem of Free Will Shaun Gallagher Department of Philosophy University of Central

Gallagher, S. 2006. Where's the action? Epiphenomenalism and the problem of free will. In W. Banks, S. Pockett, and S. Gallagher. Does Consciousness Cause Behavior? An Investigation of the Nature of Volition (109-124). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Where's the action? Epiphenomenalism and the problem of free will Shaun Gallagher Department of Philosophy University of Central Florida [email protected] Some philosophers argue that Descartes was wrong when he characterized animals as purely physical automata – robots devoid of consciousness. It seems to them obvious that animals (tigers, lions, and bears, as well as chimps, dogs, and dolphins, and so forth) are conscious. There are other philosophers who argue that it is not beyond the realm of possibilities that robots and other artificial agents may someday be conscious – and it is certainly practical to take the intentional stance toward them (the robots as well as the philosophers) even now. I'm not sure that there are philosophers who would deny consciousness to animals but affirm the possibility of consciousness in robots. In any case, and in whatever way these various philosophers define consciousness, the majority of them do attribute consciousness to humans. Amongst this group, however, there are philosophers and scientists who want to reaffirm the idea, explicated by Shadworth Holloway Hodgson in 1870, that in regard to action the presence of consciousness does not matter since it plays no causal role. Hodgson's brain generated the following thought: neural events form an autonomous causal chain that is independent of any accompanying conscious mental states. Consciousness is epiphenomenal, incapable of having any effect on the nervous system. -

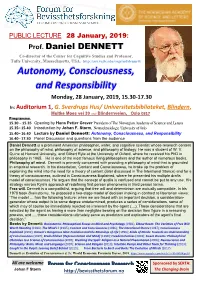

Autonomy, Consciousness, and Responsibility

PUBLIC LECTURE 28 January, 2019: Prof. Daniel DENNETT Co-director of the Center for Cognitive Studies and Professor, Tufts University, Massachusetts, USA. http://ase.tufts.edu/cogstud/dennett/ Autonomy, Consciousness, and Responsibility Monday, 28 January, 2019, 15.30-17.30 In: Auditorium 1, G. Sverdrups Hus/ Universitetsbiblioteket, Blindern, Moltke Moes vei 39 ved/ Blindernveien, Oslo 0317 Programme: 15.30 – 15.35 Opening by Hans Petter Graver President of The Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters 15.35– 15.40 Introduction by Johan F. Storm, Neurophysiology, University of Oslo 15.40– 16.40 Lecture by Daniel Dennett: Autonomy, Consciousness, and Responsibility 16.40– 17.30 Panel Discussion and questions from the audience Daniel Dennett is a prominent American philosopher, writer, and cognitive scientist whose research centers on the philosophy of mind, philosophy of science, and philosophy of biology. He was a student of W. V. Quine at Harvard University, and Gilbert Ryle at the University of Oxford, where he received his PhD in philosophy in 1965. He is one of the most famous living philosophers and the author of numerous books. Philosophy of mind. Dennett is primarily concerned with providing a philosophy of mind that is grounded in empirical research. In his dissertation, Content and Consciousness, he broke up the problem of explaining the mind into the need for a theory of content (later discussed in The Intentional Stance) and for a theory of consciousness, outlined in Consciousness Explained, where he presented his multiple drafts model of consciousness. He argues that the concept of qualia is confused and cannot be put to any use. -

Review of Freedom Evolves by Daniel Dennett (2003)

Review of Freedom Evolves by Daniel Dennett (2003) Michael Starks ABSTRACT ``People say again and again that philosophy doesn´t really progress, that we are still occupied with the same philosophical problems as were the Greeks. But the people who say this don´t understand why it has to be so. It is because our language has remained the same and keeps seducing us into asking the same questions. As long as there continues to be a verb ´to be´ that looks as if it functions in the same way as ´to eat and to drink´, as long as we still have the adjectives ´identical´, ´true´, ´false´, ´possible´, as long as we continue to talk of a river of time, of an expanse of space, etc., etc., people will keep stumbling over the same puzzling difficulties and find themselves staring at something which no explanation seems capable of clearing up. And what´s more, this satisfies a longing for the transcendent, because, insofar as people think they can see the limits of human understanding´, they believe of course that they can see beyond these.`` ´ This quote is from Ludwig Wittgenstein who redefined philosophy some 70 years ago (but most people have yet to find this out). Dennett, though he has been a philosopher for some 40 years, is one of them. It is also curious that both he and his prime antagonist, John Searle, studied under famous Wittgensteinians (Searle with John Austin, Dennett with Gilbert Ryle) but Searle got the point and Dennett did not, (though it is stretching things to call Searle or Ryle Wittgensteinians). -

Reflections on Sam Harris' “Free Will”

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Rivista Internazionale di Filosofia e Psicologia (Università degli Studi di Bari) RIVISTA INTERNAZIONALE DI FILOSOFIA E PSICOLOGIA ISSN 2039-4667; E-ISSN 2239-2629 DOI: 10.4453/rifp.2017.0018 Vol. 8 (2017), n. 3, pp. 214-230 STUDI Reflections on Sam Harris’ “Free Will” Daniel C. Dennett(α) Ricevuto: 11 aprile 2016; accettato: 10 gennaio 2017 █ Abstract In his book Free Will Sam Harris tries to persuade us to abandon the morally pernicious idea of free will. The following contribution articulates and defends a more sophisticated model of free will that is not only consistent with neuroscience and introspection but also grounds a variety of responsibility that justifies both praise and blame, reward and punishment. This begins with the long lasting parting of opinion between compatibilists (who argue that free will can live comfortably with determinism) and in- compatibilists (who deny this). While Harris dismisses compatibilism as a form of theology, this article aims at showing that Harris has underestimated and misinterpreted compatibilism and at defending a more sophisticated version of compatibilism that is impervious to Harris’ criticism. KEYWORDS: Sam Harris; Free Will; Compatibilism; Incompatibilism; Neuroscience █ Riassunto Riflessioni su “Free Will” di Sam Harris – Nel suo volume Free Will Sam Harris cerca di persua- derci ad abbandonare l’idea, a suo avviso moralmente perniciosa, del libero arbitrio. Il contributo seguente articola e difende un modello di libero arbitrio che non solo è coerente con le neuroscienze e con l’introspezione, ma che dà anche fondamento a varie forme di responsabilità, giustificando encomio, biasi- mo, premi e punizioni. -

Read Book Freedom Evolves Ebook

FREEDOM EVOLVES PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Daniel C. Dennett | 368 pages | 26 Feb 2004 | Penguin Books Ltd | 9780140283891 | English | London, United Kingdom Freedom Evolves by Daniel C. Dennett Product Details. Inspired by Your Browsing History. Labyrinths of Reason. Sleight of Mind. AI Ethics. Mark Coeckelbergh. Simply Philosophy. The Turning Point. Fritjof Capra. The Duck That Won the Lottery. Julian Baggini. Consciousness, Function, and Representation, Volume 1. A Logical Journey. Consciousness Revisited. Michael Tye. Sweet Anticipation. David Huron. Margaret Cuonzo. The Outer Limits of Reason. Noson S. Cognitive Pluralism. Steven Horst. What Is the Argument? Maralee Harrell. The Matrix and Philosophy. The Story of Philosophy. Dennett concludes by contemplating the possibility that people might be able to opt in or out of moral responsibility: surely, he suggests, given the benefits, they would choose to opt in, especially given that opting out includes such things as being imprisoned or institutionalized. Daniel Dennett also argues that no clear conclusion about volition can be derived from Benjamin Libet 's experiments supposedly demonstrating the non-existence of conscious volition. According to Dennett, ambiguities in the timings of the different events are involved. Libet tells when the readiness potential occurs objectively, using electrodes, but relies on the subject reporting the position of the hand of a clock to determine when the conscious decision was made. As Dennett points out, this is only a report of where it seems to the subject -

![[9-8-15] ALFRED REMEN MELE Office Address Department of Philosophy Florida State University Tallahassee, FL 32306-1500 Almele@Fsu.Edu](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1099/9-8-15-alfred-remen-mele-office-address-department-of-philosophy-florida-state-university-tallahassee-fl-32306-1500-almele-fsu-edu-3621099.webp)

[9-8-15] ALFRED REMEN MELE Office Address Department of Philosophy Florida State University Tallahassee, FL 32306-1500 [email protected]

[9-8-15] ALFRED REMEN MELE Office Address Department of Philosophy Florida State University Tallahassee, FL 32306-1500 [email protected] Education Ph.D., University of Michigan, 1979 B.A., Wayne State University, 1973 (with high distinction) Academic Employment History Florida State University 2000-present William H. and Lucyle T. Werkmeister Professor of Philosophy Davidson College 1995-2000 Vail Professor of Philosophy 1991-2000 Professor of Philosophy 1985-1991 Associate Professor of Philosophy 1979-1985 Assistant Professor of Philosophy Acting Chair: 1996 (fall), 1989-90 University of Michigan 1975-1979 Teaching Fellow Areas of Specialization: Philosophy of Mind; Philosophy of Action Books Author: Free: Why Science Hasn’t Disproved Free Will. Oxford University Press, 2014. A Dialogue on Free Will and Science. Oxford University Press, 2014. Backsliding: Understanding Weakness of Will. Oxford University Press, 2012. Effective Intentions: The Power of Conscious Will. Oxford University Press, 2009 (awarded American Philosophical Association’s 2013 Sanders Book Prize). Free Will and Luck. Oxford University Press, 2006. Motivation and Agency. Oxford University Press, 2003. Self-Deception Unmasked. Princeton University Press, 2001. Autonomous Agents: From Self-Control to Autonomy. Oxford University Press, 1995. Springs of Action: Understanding Intentional Behavior. Oxford University Press, 1992. 2 Irrationality: An Essay on Akrasia, Self-Deception, and Self-Control. Oxford University Press, 1987. Editor: A. Mele, ed. Surrounding Free Will. Oxford University Press, 2015. R. Baumeister, A. Mele, and K. Vohs, eds. Free Will and Consciousness: How Might They Work? Oxford University Press, 2010. M. Timmons, J. Greco, and A. Mele, eds. Rationality and the Good. Oxford University Press, 2007. -

Suicidal Utopian Delusions in the 21St Century

Suicidal Utopian Delusions in the 21st Century Philosophy, Human Nature and the Collapse of Civilization Articles and Reviews 2006-2019 4th Edition Michael Starks Reality Press Las Vegas, Nevada Copyright © 2019 by Michael Starks All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted without the express consent of the author. Printed and bound in the United States of America. 4th Edition 2019 ISBN-13: 9781796542127 “At what point is the approach of danger to be expected? I answer, if it ever reach us it must spring up amongst us; it cannot come from abroad. If destruction be our lot, we must ourselves be its author and finisher. As a nation of freemen we must live through all time or die by suicide.” Abraham Lincoln (1838) “I do not say that democracy has been more pernicious on the whole, and in the long run, than monarchy or aristocracy. Democracy has never been and never can be so durable as aristocracy or monarchy; but while it lasts, it is more bloody than either. … Remember, democracy never lasts long. It soon wastes, exhausts, and murders itself. There never was a democracy yet that did not commit suicide. It is in vain to say that democracy is less vain, less proud, less selfish, less ambitious, or less avaricious than aristocracy or monarchy. It is not true, in fact, and nowhere appears in history. Those passions are the same in all men, under all forms of simple government, and when unchecked, produce the same effects of fraud, violence, and cruelty. -

When Nice Guys Finish First: the Evolution of Cooperation, the Study of Law, and the Ordering of Legal Regimes

University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform Volume 37 2004 When Nice Guys Finish First: The Evolution of Cooperation, The Study of Law, and the Ordering of Legal Regimes Neel P. Parekh University of Michigan Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjlr Part of the Law and Society Commons, and the Science and Technology Law Commons Recommended Citation Neel P. Parekh, When Nice Guys Finish First: The Evolution of Cooperation, The Study of Law, and the Ordering of Legal Regimes, 37 U. MICH. J. L. REFORM 909 (2004). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjlr/vol37/iss3/8 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WHEN NICE GUYS FINISH FIRST: THE EVOLUTION OF COOPERATION, THE STUDY OF LAW, AND THE ORDERING OF LEGAL REGIMES Neel P. Parekh* This Note adds to the scholarship in the area of Evolutionary Analysis and the Law (EA). EA is a paradigm that comments on the implications of evolution on the law. EA recognizes that many complex human behaviors that the law seeks to regulate have evolutionary origins that remain relevant today. This Note details how an understanding of the evolutionary basis of cooperation can bring about favorable revisions and reforms in the law. -

Freedom and Ethics: Benjamin Libet's Work

Freedom and ethics: Benjamin Libet’s work Jorge Alberto Álvarez Díaz Abstract A fundamental idea to sustain basic ethical concepts such as autonomy, responsibility, etc., is “liberty”. The determinism/freedom aporia has been present in philosophical tradition since ancient world. However, after the development of neuroscience, it has been argued that freedom is merely an illusion and human beings are neurobiologically determined in our actions. This paper presents the pioneering work of Benjamin Libet on this subject (an approach that used electroencephalography and electromyography), also a critique on Libet interpretations of his results. Keywords: Bioethics. Neurosciences. Philosophy. Resumen Libertad y ética: el trabajo de Benjamin Libet Una idea fundamental para sostener conceptos éticos fundamentales, tales como el de autonomía, respon- Update Articles Update sabilidad etc., lo es la “libertad”. La aporía determinismo/libertad ha estado presente en la filosofía desde el mundo antiguo. Sin embargo, tras el desarrollo de las neurociencias, se ha planteado que la libertad es una mera ilusión y que los seres humanos estamos determinados neurobiológicamente en nuestro actuar. Este trabajo presenta los trabajos pioneros de Benjamín Libet sobre este tema (una aproximación que utilizó elec- troencefalografía y electromiografía), a la vez que realiza una crítica sobre las interpretaciones del propio Libet. Palabras-clave: Bioética. Neurociencias. Filosofía. Resumo Liberdade e ética: o trabalho de Benjamin Libet Uma ideia fundamental para sustentar conceitos éticos fundamentais, tais como autonomia, responsabilida- de, etc., é a “liberdade”. A aporia determinismo/liberdade tem sido presente na filosofia desde o mundo an- tigo. No entanto, após o desenvolvimento da neurociência, tem-se argumentado que a liberdade é uma mera ilusão e que nós seres humanos estamos neurobiologicamente determinados em nossas ações. -

Dennett in a Nutshell

Dennett in a Nutshell The following is a brief outline of Dan Dennett’s positions regarding the “problem” of consciousness. For more detail see his popular expositions: “Consciousness Explained”, “Freedom Evolves” and “Darwin’s Dangerous Idea- Evolution and the Meanings of Life”. See also the Dennett chapter summaries and discussion threads: http://forums.philosophyforums.com/thread/6031 http://forums.philosophyforums.com/thread/6331 1. Naturalism: First and foremost Dennett will simply not entertain any appeals to magic. These ideas come under a variety of headings with a full spectrum of philosophies from New Age quantum consciousness to religious belief in the immaterial soul. Therefore Dennett allows: no dualism (properties or substances), no vitalism, no soul, no epiphenomenism, no essentialism, no intrinsic supernatural or metaphysical forces or processes and most of all- NO SKYHOOKS! What does Dennett mean by a "skyhook"? The concept of "skyhook" has an uncertain origin, though Dennett cites an anecdote of "...an aeroplane pilot commanded to remain in place (aloft) for another hour, who replies: 'the machine is not fitted with skyhooks' "... Dennett goes on to explain "The skyhook concept is perhaps a descendant of the deus ex machina of ancient Greek dramaturgy: when second-rate play- wrights found their heroes into inescapable difficulties, they were often tempted to crank down a god onto the scene, like Superman, to save the situation supernaturally. ... Skyhooks would be wonderful things to have, great for lifting unwieldy objects out of difficult circumstances, and speeding up all sorts of construction projects. Sad to say, they are impossible." (DDI, p74). Ultimately, skyhooks are the Lockeian "mind-first" processes that often disregard that apparent design is the result of mindless mechanism.