Compatibilism Evolves?: on Some Varieties of Dennett Worth Wanting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Maintaining Meaningful Expressions of Romantic Love in a Material World

Reconciling Eros and Neuroscience: Maintaining Meaningful Expressions of Romantic Love in a Material World by ANDREW J. PELLITIERI* Boston University Abstract Many people currently working in the sciences of the mind believe terms such as “love” will soon be rendered philosophically obsolete. This belief results from a common assumption that such terms are irreconcilable with the naturalistic worldview that most modern scientists might require. Some philosophers reject the meaning of the terms, claiming that as science progresses words like ‘love’ and ‘happiness’ will be replaced completely by language that is more descriptive of the material phenomena taking place. This paper attempts to defend these meaningful concepts in philosophy of mind without appealing to concepts a materialist could not accept. Introduction hilosophy engages the meaning of the word “love” in a myriad of complex discourses ranging from ancient musings on happiness, Pto modern work in the philosophy of mind. The eliminative and reductive forms of materialism threaten to reduce the importance of our everyday language and devalue the meaning we attach to words like “love,” in the name of scientific progress. Faced with this threat, some philosophers, such as Owen Flanagan, have attempted to defend meaningful words and concepts important to the contemporary philosopher, while simultaneously promoting widespread acceptance of materialism. While I believe that the available work is useful, I think * [email protected]. Received 1/2011, revised December 2011. © the author. Arché Undergraduate Journal of Philosophy, Volume V, Issue 1: Winter 2012. pp. 60-82 RECONCILING EROS AND NEUROSCIENCE 61 more needs to be said about the functional role of words like “love” in the script of progressing neuroscience, and further the important implications this yields for our current mode of practical reasoning. -

Differentiating Neuroethics from Neurophilosophy

Differentiating Neuroethics From Neurophilosophy A review of Scientific and Philosophical Perspectives in Neuroethics by James J. Giordano and Bert Gordijn (Eds.) New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2010. 388 pp. ISBN 978-0-521-70303-1. $50.00 Reviewed by Amir Raz Hillel Braude Neuroethics is about gaps: the gap between neuroscience and ethics, the one between science and philosophy, and, most of all, the “hard gap” between mind and brain. The hybrid term neuroethics, put into public circulation by the late William Safire (2002), attempts to address these lacunae through an emergent discipline that draws equally from neuroscience and philosophy. What, however, distinguishes neuroethics from its sister discipline—neurophilosophy? Contrary to traditional “armchair” philosophy, neurophilosophers such as Paul and Patricia Churchland argue that philosophy needs to take account of empirical neuroscience data regarding the mind–brain relation. Similarly, neuropsychologists and neuroscientists should be amenable to philosophical insights and the conceptual rigor of the philosophical method. Joshua Greene’s neuroimaging studies of participants making moral decisions provide a good example of this symbiotic relation between neuroscience and philosophy (Greene, Sommerville, Nystrom, Darley, & Cohen, 2001). A number of possible answers to the distinction between neuroethics and neurophilosophy emerge from Scientific and Philosophical Perspectives in Neuroethics, edited by James J. Giordano and Bert Gordijn. First, neuroethics emerges from the discipline of bioethics and, as such, specifically deals with ethical issues related to neuroscience. As Neil Levy says in his preface to the book, “Techniques and technologies stemming from the science of the mind raise . profound questions about what it means to be human, and pose greater challenges to moral thought” (p. -

Psychological Arguments for Free Will DISSERTATION Presented In

Psychological Arguments for Free Will DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Andrew Kissel Graduate Program in Philosophy The Ohio State University 2017 Dissertation Committee: Richard Samuels, Advisor Declan Smithies Abraham Roth Copyrighted by Andrew Kissel 2017 Abstract It is a widespread platitude among many philosophers that, regardless of whether we actually have free will, it certainly appears to us that we are free. Among libertarian philosophers, this platitude is sometimes deployed in the context of psychological arguments for free will. These arguments are united under the idea that widespread claims of the form, “It appears to me that I am free,” on some understanding of appears, justify thinking that we are probably free in the libertarian sense. According to these kinds of arguments, the existence of free will is supposed to, in some sense, “fall out” of widely accessible psychological states. While there is a long history of thinking that widespread psychological states support libertarianism, the arguments are often lurking in the background rather than presented at face value. This dissertation consists of three free-standing papers, each of which is motivated by taking seriously psychological arguments for free will. The dissertation opens with an introduction that presents a framework for mapping extant psychological arguments for free will. In the first paper, I argue that psychological arguments relying on widespread belief in free will, combined with doxastic conservative principles, are likely to fail. In the second paper, I argue that psychological arguments involving an inference to the best explanation of widespread appearances of freedom put pressure on non-libertarians to provide an adequate alternative explanation. -

Free Will and Determinism Debate on the Philosophy Forum

Free Will and Determinism debate on the Philosophy Forum. 6/2004 All posts by John Donovan unless noted otherwise. The following link is an interesting and enjoyable interview with Daniel Dennett discussing the ideas in his latest book where he describes how "free will" in humans and physical "determinism" are entirely compatible notions if one goes beyond the traditional philosophical arguments and examines these issues from an evolutionary viewpoint. http://www.reason.com/0305/fe.rb.pulling.shtml A short excerpt: Reason: A response might be that you’re just positing a more complicated form of determinism. A bird may be more "determined" than we are, but we nevertheless are determined. Dennett: So what? Determinism is not a problem. What you want is freedom, and freedom and determinism are entirely compatible. In fact, we have more freedom if determinism is true than if it isn’t. Reason: Why? Dennett: Because if determinism is true, then there’s less randomness. There’s less unpredictability. To have freedom, you need the capacity to make reliable judgments about what’s going to happen next, so you can base your action on it. Imagine that you’ve got to cross a field and there’s lightning about. If it’s deterministic, then there’s some hope of knowing when the lightning’s going to strike. You can get information in advance, and then you can time your run. That’s much better than having to rely on a completely random process. If it’s random, you’re at the mercy of it. A more telling example is when people worry about genetic determinism, which they completely don’t understand. -

Where's the Action? Epiphenomenalism and the Problem of Free Will Shaun Gallagher Department of Philosophy University of Central

Gallagher, S. 2006. Where's the action? Epiphenomenalism and the problem of free will. In W. Banks, S. Pockett, and S. Gallagher. Does Consciousness Cause Behavior? An Investigation of the Nature of Volition (109-124). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Where's the action? Epiphenomenalism and the problem of free will Shaun Gallagher Department of Philosophy University of Central Florida [email protected] Some philosophers argue that Descartes was wrong when he characterized animals as purely physical automata – robots devoid of consciousness. It seems to them obvious that animals (tigers, lions, and bears, as well as chimps, dogs, and dolphins, and so forth) are conscious. There are other philosophers who argue that it is not beyond the realm of possibilities that robots and other artificial agents may someday be conscious – and it is certainly practical to take the intentional stance toward them (the robots as well as the philosophers) even now. I'm not sure that there are philosophers who would deny consciousness to animals but affirm the possibility of consciousness in robots. In any case, and in whatever way these various philosophers define consciousness, the majority of them do attribute consciousness to humans. Amongst this group, however, there are philosophers and scientists who want to reaffirm the idea, explicated by Shadworth Holloway Hodgson in 1870, that in regard to action the presence of consciousness does not matter since it plays no causal role. Hodgson's brain generated the following thought: neural events form an autonomous causal chain that is independent of any accompanying conscious mental states. Consciousness is epiphenomenal, incapable of having any effect on the nervous system. -

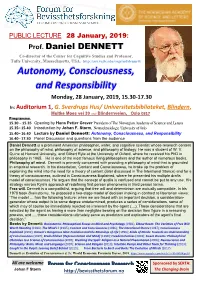

Autonomy, Consciousness, and Responsibility

PUBLIC LECTURE 28 January, 2019: Prof. Daniel DENNETT Co-director of the Center for Cognitive Studies and Professor, Tufts University, Massachusetts, USA. http://ase.tufts.edu/cogstud/dennett/ Autonomy, Consciousness, and Responsibility Monday, 28 January, 2019, 15.30-17.30 In: Auditorium 1, G. Sverdrups Hus/ Universitetsbiblioteket, Blindern, Moltke Moes vei 39 ved/ Blindernveien, Oslo 0317 Programme: 15.30 – 15.35 Opening by Hans Petter Graver President of The Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters 15.35– 15.40 Introduction by Johan F. Storm, Neurophysiology, University of Oslo 15.40– 16.40 Lecture by Daniel Dennett: Autonomy, Consciousness, and Responsibility 16.40– 17.30 Panel Discussion and questions from the audience Daniel Dennett is a prominent American philosopher, writer, and cognitive scientist whose research centers on the philosophy of mind, philosophy of science, and philosophy of biology. He was a student of W. V. Quine at Harvard University, and Gilbert Ryle at the University of Oxford, where he received his PhD in philosophy in 1965. He is one of the most famous living philosophers and the author of numerous books. Philosophy of mind. Dennett is primarily concerned with providing a philosophy of mind that is grounded in empirical research. In his dissertation, Content and Consciousness, he broke up the problem of explaining the mind into the need for a theory of content (later discussed in The Intentional Stance) and for a theory of consciousness, outlined in Consciousness Explained, where he presented his multiple drafts model of consciousness. He argues that the concept of qualia is confused and cannot be put to any use. -

Review of Freedom Evolves by Daniel Dennett (2003)

Review of Freedom Evolves by Daniel Dennett (2003) Michael Starks ABSTRACT ``People say again and again that philosophy doesn´t really progress, that we are still occupied with the same philosophical problems as were the Greeks. But the people who say this don´t understand why it has to be so. It is because our language has remained the same and keeps seducing us into asking the same questions. As long as there continues to be a verb ´to be´ that looks as if it functions in the same way as ´to eat and to drink´, as long as we still have the adjectives ´identical´, ´true´, ´false´, ´possible´, as long as we continue to talk of a river of time, of an expanse of space, etc., etc., people will keep stumbling over the same puzzling difficulties and find themselves staring at something which no explanation seems capable of clearing up. And what´s more, this satisfies a longing for the transcendent, because, insofar as people think they can see the limits of human understanding´, they believe of course that they can see beyond these.`` ´ This quote is from Ludwig Wittgenstein who redefined philosophy some 70 years ago (but most people have yet to find this out). Dennett, though he has been a philosopher for some 40 years, is one of them. It is also curious that both he and his prime antagonist, John Searle, studied under famous Wittgensteinians (Searle with John Austin, Dennett with Gilbert Ryle) but Searle got the point and Dennett did not, (though it is stretching things to call Searle or Ryle Wittgensteinians). -

Two Dogmas of Reductionism: on the Irreducibility of Self-Consciousness and the Impossibility of Neurophilosophy

Athens Journal of Humanities & Arts - Volume 1, Issue 2 – Pages 135-146 Two Dogmas of Reductionism: On the Irreducibility of Self-Consciousness and the Impossibility of Neurophilosophy By Joseph Thompson Two fundamental assumptions have become dogma in contemporary Anglo-American philosophy of consciousness: that everything about consciousness can be explained in physical terms, and that neuroscience provides the uniquely authoritative methodology for approaching the essential questions. But there has never yet been a successful physical explanation of subjective first-person experience, and reductionism fails to account adequately for thought, reason, and a full range of objects proper to philosophy. Tracking the deep divide within the analytic tradition, I bring a ‘continental’ (German) perspective to bear on recent work from Nagel and Chalmers which shows the reductionist neuroscientific agenda to be incapable of completion, for systematic reasons. Physicalism can explain only structure, function, and mechanism; but self-consciousness is always already embodied and embedded in multiple contexts beyond the structures and functions of brain activity. Consciousness needs to account for itself, to itself, on the terms in which it experiences itself. No explanation of the form provided by ‘neurophilosophy’ is adequate to the most fundamental and essential phenomena of self- consciousness, and neurophilosophy can never philosophically explain or justify itself on its own terms and by its own methodology. These are insuperable limitations for any explanation aspiring to be comprehensive, and such problems have brought contemporary antireductionists in the English-speaking world back around to positions which strongly resemble the ontology and phenomenology of German-language philosophers, particularly Kant, Hegel, and Heidegger. -

Religion, Science, and the Conscious Self: Bio-Psychological Explanation and the Debate Between Dualism and Naturalism

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2011 Religion, Science, and the Conscious Self: Bio-Psychological Explanation and the Debate Between Dualism and Naturalism Paul J. Voelker Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Voelker, Paul J., "Religion, Science, and the Conscious Self: Bio-Psychological Explanation and the Debate Between Dualism and Naturalism" (2011). Dissertations. 242. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/242 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 2011 Paul J. Voelker LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO RELIGION, SCIENCE, AND THE CONSCIOUS SELF: BIO-PSYCHOLOGICAL EXPLANATION AND THE DEBATE BETWEEN DUALISM AND NATURALISM A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY PROGRAM IN THEOLOGY BY PAUL J. VOELKER CHICAGO, ILLINOIS MAY 2011 Copyright by Paul J. Voelker, 2011 All rights reserved. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many people helped to make this dissertation project a concrete reality. First, and foremost, I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. John McCarthy. John’s breadth and depth of knowledge made for years of stimulating, challenging conversation, and I am grateful for his constant support. Dr. Michael Schuck also provided for much good conversation during my time at Loyola, and I am grateful to Mike for taking time from a hectic schedule to serve on my dissertation committee. -

CONSCIOUSNESS 'THE Sour

( Fall 1995 Vol.15, No.4 HMMM... CONSCIOUSNESS 'THE sour. ABE ARTIFICIAL IIITELLIGENCE Exclusive Interviews with Cognitive Scientists Patricia Smith Churchland and Daniel C. Dennett BERTRAND RUSSELL Also: The Disneyfication of America Situation Ethics in Medicine 74957 Reactionar Black Nationalism FALL 1995, VOL. 15, NO. 4 ISSN 0272-0701 !ee WTI : Contents Editor: Paul Kurtz Executive Editor: Timothy J. Madigan Managing Editor: Andrea Szalanski 3 LETTERS TO THE EDITOR Senior Editors: Vern Bullough, Thomas W. Flynn, R. Joseph Hoffmann, Gerald Larue, Gordon Stein 5 EDITORIALS Contributing Editors: Robert S. Alley, Joe E. Barnhart, David Berman, Notes from the Editor: Pro Ecclesia et Commercia, Paul Kurtz I H. James Birx, Jo Ann Boydston, Bonnie Bullough, Reactionary Black Nationalism: Authoritarianism in the Name of Paul Edwards, Albert Ellis, Roy P. Fairfield, Charles W. Faulkner, Antony Flew, Levi Fragell, Adolf Freedom, Norm R. Allen, Jr. / The Founding Fathers Were Not Grünbaum, Marvin Kohl, Jean Kotkin, Thelma Lavine, Tibor Machan, Ronald A. Lindsay, Michael Christian, Steven Morris I Religious Right to Bolt GOP?, Skipp Martin, Delos B. McKown, Lee Nisbet, John Novak, Porteous I Humanist Potpourri, Warren Allen Smith Skipp Porteous, Howard Radest, Robert Rimmer, Michael Rockier, Svetozar Stojanovic, Thomas Szasz, Roh Tielman 16 NEWS AND VIEWS V. M. Torkunde, Richard Taylor, Associate Editors: Molleen Matsumura, Lois Porter 19 CONSCIOUSNESS REVISITED Editorial Associates: 19 FI Interview: A Conversation with Daniel Dennett Doris Doyle, Thomas Franczyk, Roger Greeley, James Martin-Diaz, Steven L. Mitchell, Warren 22 FI Interview: The Neurophilosophy of Patricia Smith Churchland Allen Smith 25 Neurological Bases of Modern Humanism José Delgado Cartoonist: Don Addis 29 Revisiting 'New Conceptions of the Mind' Noel W Smith CODESH. -

Understanding Patricia Churchland's

FACTS AGAINST SPECULATIONS: UNDERSTANDING PATRICIA CHURCHLAND’S NEUROPHILOSOPHY By FARINOLA AUGUSTINE AKINTUNDE INTRODUCTION “The more informed our brains are by science at all levels of analysis, the better will be our brains’ theoretical evolution” -Patricia Churchland (1986) Discourse in philosophy about how human being could attain knowledge, right from the medieval period to the modern period has witnessed scholars making references to the ‘intellect’, the ‘mind’ or the ‘soul’. A radical change in this linguistic reference was challenged by Gilbert Ryle with his analysis of ‘ghost in the machine’. It is appear to be a primitive way of thinking, especially in our age, to still hold on to the view that there is an invisible and immaterial substance, other than the brain, that influence human or regulate human feelings, decisions and means of knowing. Meanwhile, within the tradition of philosophy, idealists and rationalists (along with religiously inclined scholars) will prefer to be consistent with their metaphysical heritage and postulations by challenging any materialistic reduction of a human person to just a material being whose movements, actions, and phenomena surrounding him could be explain simply in empirical terms. Furthermore, a quick glance at the history of ideas, one would recall a moment (starting from David Hume down to the emergence of logical empiricists/positivists and linguists) in which a brutal war was launched against metaphysical ideas, leading to a periodical triumph of science. Though this tension was resolved by scholars like Thomas Kuhn, Karl Popper, Paul K Feyerabend and most post-modern scholars, yet it creates two camps among the scholars of science and philosophy – as the academic protector of metaphysics. -

Introductory Lectures: the Nature and History of Cognitive Science Chapter 4: Philosophy’S Convergence Towards Cognitive Science by Dr

Introductory Lectures: The Nature and History of Cognitive Science Chapter 4: Philosophy’s Convergence Towards Cognitive Science By Dr. Charles Wallis Last revision: 9/24/2018 Chapter Outline 4.1 Introduction 4.2 The Scientific Explosion of the Early 20th Century 4.3 The Logical and Mathematical Explosion of the Early 20th Century 4.4 The Rise Logical Empiricism 4.5 Logical Behaviorism 4.6 Three Problems for Logical Behaviorism 4.7 Identity Theories: Reduction Through Reference Equivalence Rather Than Meaning Equivalence 4.8 Identity Theories: Type-Type Identity 4.9 Two Arguments For Type-Type Identity Theory 4.10 Identity Theories: Token-Token Identity 4.11 Functionalism 4.12 Computationalism 4.13 Property Dualism 4.14 Eliminative Materialism 4.15 Glossary of Key Terms 4.16 Bibliography The 20th Century and the Semantic Twist 4.1 Introduction Recall that ontological frameworks provide a general framework within which theorists specify domains of inquiry and construct theories to predict, manipulate, and explain phenomena within the domain. Once researchers articulate an ontological framework with sufficient clarity they begin to formulate and test theories. Chapter two ends with the suggestion that oppositional substance dualists face two major challenges in their attempt to transition from the articulation of an ontological framework to the formulation and testing of theories purporting to predict, manipulate, and explain mental phenomena. On the one hand, oppositional substance dualists have problems formulating theories providing explanations, predictions, and manipulations of the continual, seamless interaction between the mental and the physical. Philosophers often call this the interaction problem. On the other hand, the very nature of a mental substance--substance defined so as to share no properties with physical substance--gives rise to additional challenges.