Religion, Science, and the Conscious Self: Bio-Psychological Explanation and the Debate Between Dualism and Naturalism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Critical Theory, Historical Materialism, and the Ostensible End of Marxism: the Poverty of Theory Revisited

Critical Theory, Historical Materialism, and the Ostensible End of Marxism: The Poverty of Theory Revisited BRYAN D. PALMER Summary: This essay notes the extent to which poststructuralism/postmodernism have generally espoused hostility to historical materialism, surveys some representative examples of historical writing that have gravitated toward the new critical theory in opposition to Marxism, and closes with a discussion of the ironic evolution of a poststructurally inclined, anti-Marxist historiography. Counter to the prevailing ideological consensus that Marxism has been brought to its interpretive knees by a series of analytic challenges and the political collapse of the world's ostensibly "socialist" states, this essay argues that historical materialism has lost neither its power to interpret the past nor its relevance to the contemporary intellectual terrain. It is now a decade-and-one-half since Edward Thompson penned The Poverty of Theory: or an Orrery of Errors, and ten times as many years have passed since the publication of Marx's The Poverty of Philosophy.1 Whatever one may think about the advances in knowledge associated with historical materialism and Marxism, particularly in terms of the practice of historical writing, there is no denying that this sesquicentennial has been a problematic period in the making of communist society; the last fifteen years, moreover, are associated with the bleak end of socialism and the passing of Marxism as an intellectual force. Indeed, it is a curious conjuncture of our times that the -

Mindfulness and the 12 Steps

mindfulness and the 12 steps with Thérèse Jacobs-Stewart Resting the Mind • Assume a body position where your spine is straight and your body relaxed. • Allow your mind to rest for a few minutes, letting whatever happens-or doesn’t happen-be a part of the experiment. • Relax with whatever arises. • When time is up, ask yourself, “How was that?” (Don’t judge; just review what happened and how you felt.) • The only difference between meditation and the ordinary process of feeling, thinking, feeling, and sensation is the application of the “bare awareness.” Mindfulness Meditation Consciously bring awareness to your here-and-now experience with openness, interest, and self-acceptance. 1 Ways Mindfulness and Meditation Help the Therapist • Offers idea of “strengthening the heart” vs. western psychology’s concept of “self-care.” • Reduces compassion fatigue, renews energy, and counteracts burn-out. • Deepens capacity for a compassionate and non- judging presence. • Increases ability to abide with difficult emotions, offering hope and relief. • Sharpens awareness of therapist’s own reactions. Specific Brain States Correlate with Happiness Brain Activity Associated with Mindfulness Meditation 2 Meditation Changes the Circuitry of the Brain Jacobs-Stewart, Paths Are Made by Walking, 2003 “Meditation training can change the brain and forever alter our sense of well-being.” Richard Davidson Laboratory for Neuroaffective Science University of Wisconsin, Madison 3 Effects of Mindfulness on the Addictive Brain • Enhances neural plasticity. • Reduces activity in the amygdala. • Thickens the bilateral, prefrontal right-insular region of the brain. • Integrates prefrontal regulation and limbic emotion activation. • Builds new neural connections among brain cells for self-observation, optimism, and well-being. -

Philosophy of Science and Philosophy of Chemistry

Philosophy of Science and Philosophy of Chemistry Jaap van Brakel Abstract: In this paper I assess the relation between philosophy of chemistry and (general) philosophy of science, focusing on those themes in the philoso- phy of chemistry that may bring about major revisions or extensions of cur- rent philosophy of science. Three themes can claim to make a unique contri- bution to philosophy of science: first, the variety of materials in the (natural and artificial) world; second, extending the world by making new stuff; and, third, specific features of the relations between chemistry and physics. Keywords : philosophy of science, philosophy of chemistry, interdiscourse relations, making stuff, variety of substances . 1. Introduction Chemistry is unique and distinguishes itself from all other sciences, with respect to three broad issues: • A (variety of) stuff perspective, requiring conceptual analysis of the notion of stuff or material (Sections 4 and 5). • A making stuff perspective: the transformation of stuff by chemical reaction or phase transition (Section 6). • The pivotal role of the relations between chemistry and physics in connection with the question how everything fits together (Section 7). All themes in the philosophy of chemistry can be classified in one of these three clusters or make contributions to general philosophy of science that, as yet , are not particularly different from similar contributions from other sci- ences (Section 3). I do not exclude the possibility of there being more than three clusters of philosophical issues unique to philosophy of chemistry, but I am not aware of any as yet. Moreover, highlighting the issues discussed in Sections 5-7 does not mean that issues reviewed in Section 3 are less im- portant in revising the philosophy of science. -

Reviewers Who Completed a Review During 2001

REVIEWERS LIST The constituency of the ARCHIVES comprises a “university” of often interchangeable writers and readers, students, knowledgeable practitioners, and scholars of medicine and sciences underlying the field of psychiatry. The editors are deeply grateful to the many colleagues listed here for their generous assistance in editorial critique and review. The donation of their special expertise is a necessary contribution on which the intellectual standards in the field heavily depend. Jack D. Barchas, MD Editor Larry Abel Francesc Artigas Chawki Benkelfat Evelyn Bromet James Abelson Robert Asarnow Lisa Berkman Judith S. Brook Anissa Abi-Dargham Wesson Ashford Karen Faith Berman Robert K. Brooner Howard B. Abikoff Boris Astrachan Robert Berman George W. Brown Lyn Y. Abramson Evelyn Attia Greg Berns Marty Bruce T. M. Achenbach S. Avenevoli Wade Berrettini Gerard E. Bruder Kenneth M. Adams Elizabeth Auchincloss Larry E. Beutler Maja Bucan Lawrence E.Adler David Avery Joseph Biederman Robert W. Buchanan Lenard A. Adler Thomas Babor Laura Bierut Kathleen K. Bucholz Nancy E. Adler Nadia Badawi George Bigelow Monte Buchsbaum Ralph Adolphs Alan D. Baddeley Robert Bilder Alan J. Budney George Aghajanian Lee Baer Rene Binder Stephen L. Buka W. Stewart Agras J. Michael Bailey Ray Bingham William E. Bunney Schahram Akbarian Ross J. Baldessarini Niels Birbaumer Audrey Burnam Huda Akil James C. Ballenger Boris Birmaher Barbara J. Burns Hagop S. Akiskal J. Bancroft Donald Black Terry Bush Claude Alain Karen J. Bandeen-Roche D. H. Blackwood Daniel Buysse Marigarita Alegria Deanna M. Barch Jack Blaine William Byne Georgios Alexopoulos John C. Barefoot Helen Blair Simpson Robert P. Cabaj Kimmo Alho Russell A. -

Comment Fundamentalism and Science

SISSA – International School for Advanced Studies Journal of Science Communication ISSN 1824 – 2049 http://jcom.sissa.it/ Comment Fundamentalism and science Massimo Pigliucci The many facets of fundamentalism. There has been much talk about fundamentalism of late. While most people's thought on the topic go to the 9/11 attacks against the United States, or to the ongoing war in Iraq, fundamentalism is affecting science and its relationship to society in a way that may have dire long-term consequences. Of course, religious fundamentalism has always had a history of antagonism with science, and – before the birth of modern science – with philosophy, the age-old vehicle of the human attempt to exercise critical thinking and rationality to solve problems and pursue knowledge. “Fundamentalism” is defined by the Oxford Dictionary of the Social Sciences 1 as “A movement that asserts the primacy of religious values in social and political life and calls for a return to a 'fundamental' or pure form of religion.” In its broadest sense, however, fundamentalism is a form of ideological intransigence which is not limited to religion, but includes political positions as well (for example, in the case of some extreme forms of “environmentalism”). In the United States, the main version of the modern conflict between science and religious fundamentalism is epitomized by the infamous Scopes trial that occurred in 1925 in Tennessee, when the teaching of evolution was challenged for the first time 2,3. That battle is still being fought, for example in Dover, Pennsylvania, where at the time of this writing a court of law is considering the legitimacy of teaching “intelligent design” (a form of creationism) in public schools. -

Maintaining Meaningful Expressions of Romantic Love in a Material World

Reconciling Eros and Neuroscience: Maintaining Meaningful Expressions of Romantic Love in a Material World by ANDREW J. PELLITIERI* Boston University Abstract Many people currently working in the sciences of the mind believe terms such as “love” will soon be rendered philosophically obsolete. This belief results from a common assumption that such terms are irreconcilable with the naturalistic worldview that most modern scientists might require. Some philosophers reject the meaning of the terms, claiming that as science progresses words like ‘love’ and ‘happiness’ will be replaced completely by language that is more descriptive of the material phenomena taking place. This paper attempts to defend these meaningful concepts in philosophy of mind without appealing to concepts a materialist could not accept. Introduction hilosophy engages the meaning of the word “love” in a myriad of complex discourses ranging from ancient musings on happiness, Pto modern work in the philosophy of mind. The eliminative and reductive forms of materialism threaten to reduce the importance of our everyday language and devalue the meaning we attach to words like “love,” in the name of scientific progress. Faced with this threat, some philosophers, such as Owen Flanagan, have attempted to defend meaningful words and concepts important to the contemporary philosopher, while simultaneously promoting widespread acceptance of materialism. While I believe that the available work is useful, I think * [email protected]. Received 1/2011, revised December 2011. © the author. Arché Undergraduate Journal of Philosophy, Volume V, Issue 1: Winter 2012. pp. 60-82 RECONCILING EROS AND NEUROSCIENCE 61 more needs to be said about the functional role of words like “love” in the script of progressing neuroscience, and further the important implications this yields for our current mode of practical reasoning. -

Theology, History, and Religious Identification: Hegelian Methods in the Study of Religion

Theology, History, and Religious Identification: Hegelian Methods in the Study of Religion Kevin J. Harrelson Sophia International Journal for Philosophy of Religion, Metaphysical Theology and Ethics ISSN 0038-1527 SOPHIA DOI 10.1007/s11841-012-0334-0 1 23 Your article is protected by copyright and all rights are held exclusively by Springer Science+Business Media B.V.. This e-offprint is for personal use only and shall not be self- archived in electronic repositories. If you wish to self-archive your work, please use the accepted author’s version for posting to your own website or your institution’s repository. You may further deposit the accepted author’s version on a funder’s repository at a funder’s request, provided it is not made publicly available until 12 months after publication. 1 23 Author's personal copy SOPHIA DOI 10.1007/s11841-012-0334-0 Theology, History, and Religious Identification: Hegelian Methods in the Study of Religion Kevin J. Harrelson # Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2012 Abstract This essay deals with the impact of Hegel's philosophy of religion by examining his positions on religious identity and on the relationship between theol- ogy and history. I argue that his criterion for religious identity was socio-historical, and that his philosophical theology was historical rather than normative. These positions help explain some historical peculiarities regarding the effect of his philos- ophy of religion. Of particular concern is that although Hegel’s own aims were apologetic, his major influence on religious thought was in the development of various historical and critical approaches to religion. -

Life with Augustine

Life with Augustine ...a course in his spirit and guidance for daily living By Edmond A. Maher ii Life with Augustine © 2002 Augustinian Press Australia Sydney, Australia. Acknowledgements: The author wishes to acknowledge and thank the following people: ► the Augustinian Province of Our Mother of Good Counsel, Australia, for support- ing this project, with special mention of Pat Fahey osa, Kevin Burman osa, Pat Codd osa and Peter Jones osa ► Laurence Mooney osa for assistance in editing ► Michael Morahan osa for formatting this 2nd Edition ► John Coles, Peter Gagan, Dr. Frank McGrath fms (Brisbane CEO), Benet Fonck ofm, Peter Keogh sfo for sharing their vast experience in adult education ► John Rotelle osa, for granting us permission to use his English translation of Tarcisius van Bavel’s work Augustine (full bibliography within) and for his scholarly advice Megan Atkins for her formatting suggestions in the 1st Edition, that have carried over into this the 2nd ► those generous people who have completed the 1st Edition and suggested valuable improvements, especially Kath Neehouse and friends at Villanova College, Brisbane Foreword 1 Dear Participant Saint Augustine of Hippo is a figure in our history who has appealed to the curiosity and imagination of many generations. He is well known for being both sinner and saint, for being a bishop yet also a fellow pilgrim on the journey to God. One of the most popular and attractive persons across many centuries, his influence on the church has continued to our current day. He is also renowned for his influ- ence in philosophy and psychology and even (in an indirect way) art, music and architecture. -

Please Do Not Cite. a PROBLEM for CHRISTIAN MATERIALISM

This is a Draft! Please do not Cite. WHEN CITING ALWAYS REFER TO THE FINAL VERSION PUBLISHED IN EUROPEAN JOURNAL FOR PHILOSOPHY OF RELIGION, VOL. 10, NO. 3., 205–213. WITH DOI: 10.24204/EJPR.V10I3.2631 A PROBLEM FOR CHRISTIAN MATERIALISM Elliot Knuths1 Northwestern University Peter van Inwagen and Dean Zimmerman have attempted to demonstrate the metaphysical compatibility of materialism and life after death as it is understood in orthodox Christianity. According to van Inwagen’s simulacrum account of resurrection, God replaces either the whole person or some crucial part of the “core person” with an exact replica at the moment of the person’s death.2 This removed original person — or frag- ment of an original person — provides the basis for personal continuity between an individual in her previ- DOI: 10.24204/EJPR.V10I3.2631 ous life and her post-resurrection life in the world to come. Alternatively, Zimmerman’s “Falling Elevator Model” of resurrection claims that, at the moment just before death, the body undergoes fission, leaving a nonliving lump of matter (a corpse) in the present and a living copy at some other point in space-time.3 In a recent paper, Taliaferro and I criticized these positions,4 arguing that each one lacks phenomenological realism, the quality of satisfactorily reflecting ordinary experience. That article focused primarily on what we consider the methodological shortcomings of van Inwagen’s and Zimmerman’s accounts of resurrection . Citable Version has Version . Citable in materialist terms and other philosophical explanations and thought experiments which clash with ordi- nary experience. We also raised in passing a more substantive challenge for explanations of resurrection in materialist terms which arises from scripture rather than a priori contemplation. -

European Journal of Pragmatism and American Philosophy, IV-2 | 2012 Darwinized Hegelianism Or Hegelianized Darwinism? 2

European Journal of Pragmatism and American Philosophy IV-2 | 2012 Wittgenstein and Pragmatism Darwinized Hegelianism or Hegelianized Darwinism? Mathias Girel Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/ejpap/736 DOI: 10.4000/ejpap.736 ISSN: 2036-4091 Publisher Associazione Pragma Electronic reference Mathias Girel, « Darwinized Hegelianism or Hegelianized Darwinism? », European Journal of Pragmatism and American Philosophy [Online], IV-2 | 2012, Online since 24 December 2012, connection on 21 April 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ejpap/736 ; DOI : 10.4000/ejpap.736 This text was automatically generated on 21 April 2019. Author retains copyright and grants the European Journal of Pragmatism and American Philosophy right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Darwinized Hegelianism or Hegelianized Darwinism? 1 Darwinized Hegelianism or Hegelianized Darwinism? Mathias Girel 1 It has been said that Peirce was literally talking “with the rifle rather than with the shot gun or water hose” (Perry 1935, vol. 2: 109). Readers of his review of James’s Principles can easily understand why. In some respects, the same might be true of the series of four books Joseph Margolis has been devoting to pragmatism since 2000. One of the first targets of Margolis’s rereading was the very idea of a ‘revival’ of pragmatism (a ‘revival’ of something that never was, in some ways), and, with it, the idea that the long quarrel between Rorty and Putnam was really a quarrel over pragmatism (that is was a pragmatist revival, in some ways). The uncanny thing is that, the more one read the savory chapters of the four books, the more one feels that the hunting season is open, but that the game is not of the usual kind and looks more like zombies, so to speak. -

Differentiating Neuroethics from Neurophilosophy

Differentiating Neuroethics From Neurophilosophy A review of Scientific and Philosophical Perspectives in Neuroethics by James J. Giordano and Bert Gordijn (Eds.) New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2010. 388 pp. ISBN 978-0-521-70303-1. $50.00 Reviewed by Amir Raz Hillel Braude Neuroethics is about gaps: the gap between neuroscience and ethics, the one between science and philosophy, and, most of all, the “hard gap” between mind and brain. The hybrid term neuroethics, put into public circulation by the late William Safire (2002), attempts to address these lacunae through an emergent discipline that draws equally from neuroscience and philosophy. What, however, distinguishes neuroethics from its sister discipline—neurophilosophy? Contrary to traditional “armchair” philosophy, neurophilosophers such as Paul and Patricia Churchland argue that philosophy needs to take account of empirical neuroscience data regarding the mind–brain relation. Similarly, neuropsychologists and neuroscientists should be amenable to philosophical insights and the conceptual rigor of the philosophical method. Joshua Greene’s neuroimaging studies of participants making moral decisions provide a good example of this symbiotic relation between neuroscience and philosophy (Greene, Sommerville, Nystrom, Darley, & Cohen, 2001). A number of possible answers to the distinction between neuroethics and neurophilosophy emerge from Scientific and Philosophical Perspectives in Neuroethics, edited by James J. Giordano and Bert Gordijn. First, neuroethics emerges from the discipline of bioethics and, as such, specifically deals with ethical issues related to neuroscience. As Neil Levy says in his preface to the book, “Techniques and technologies stemming from the science of the mind raise . profound questions about what it means to be human, and pose greater challenges to moral thought” (p. -

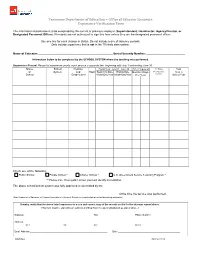

Experience Verification Form

Tennessee Department of Education – Office of Educator Licensure Experience Verification Form The information listed below is to be completed by the current or previous employer (Superintendent, Headmaster, Agency Director, or Designated Personnel Officer). Principals are not authorized to sign this form unless they are the designated personnel officer. Use one line for each change in status. Do not include leave of absence periods. Only include experience that is not in the TN state data system. Name of Educator: ________________________________________________ Social Security Number: _________________________ Information below to be completed by the SCHOOL SYSTEM where the teaching was performed. Experience Record: Please list experience yearly, each year on a separate line, beginning with July 1 and ending June 30. Name School Position Fiscal Year, July 01 - June 30 Time Employed % Time, Total of System and State Beginning Date Ending Date Months / Days Ex. Part-time, Days in Month/Day/Year Month/Day/Year Full-time School Year School Grade Level Per Year Check one of the following: Public School Private School * Charter School * U.S. Government Service Teaching Program * ** Please note: If non-public school you must identify accreditation. The above school/school system was fully approved or accredited by the ____________________________________________________________________ at the time the service was performed. (State Department of Education, or Regional Association of Colleges & Schools, or recognized private school accrediting