An Interpretationist Approach to the Thinking Mind DISSERTATION

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mindfulness and the 12 Steps

mindfulness and the 12 steps with Thérèse Jacobs-Stewart Resting the Mind • Assume a body position where your spine is straight and your body relaxed. • Allow your mind to rest for a few minutes, letting whatever happens-or doesn’t happen-be a part of the experiment. • Relax with whatever arises. • When time is up, ask yourself, “How was that?” (Don’t judge; just review what happened and how you felt.) • The only difference between meditation and the ordinary process of feeling, thinking, feeling, and sensation is the application of the “bare awareness.” Mindfulness Meditation Consciously bring awareness to your here-and-now experience with openness, interest, and self-acceptance. 1 Ways Mindfulness and Meditation Help the Therapist • Offers idea of “strengthening the heart” vs. western psychology’s concept of “self-care.” • Reduces compassion fatigue, renews energy, and counteracts burn-out. • Deepens capacity for a compassionate and non- judging presence. • Increases ability to abide with difficult emotions, offering hope and relief. • Sharpens awareness of therapist’s own reactions. Specific Brain States Correlate with Happiness Brain Activity Associated with Mindfulness Meditation 2 Meditation Changes the Circuitry of the Brain Jacobs-Stewart, Paths Are Made by Walking, 2003 “Meditation training can change the brain and forever alter our sense of well-being.” Richard Davidson Laboratory for Neuroaffective Science University of Wisconsin, Madison 3 Effects of Mindfulness on the Addictive Brain • Enhances neural plasticity. • Reduces activity in the amygdala. • Thickens the bilateral, prefrontal right-insular region of the brain. • Integrates prefrontal regulation and limbic emotion activation. • Builds new neural connections among brain cells for self-observation, optimism, and well-being. -

Reviewers Who Completed a Review During 2001

REVIEWERS LIST The constituency of the ARCHIVES comprises a “university” of often interchangeable writers and readers, students, knowledgeable practitioners, and scholars of medicine and sciences underlying the field of psychiatry. The editors are deeply grateful to the many colleagues listed here for their generous assistance in editorial critique and review. The donation of their special expertise is a necessary contribution on which the intellectual standards in the field heavily depend. Jack D. Barchas, MD Editor Larry Abel Francesc Artigas Chawki Benkelfat Evelyn Bromet James Abelson Robert Asarnow Lisa Berkman Judith S. Brook Anissa Abi-Dargham Wesson Ashford Karen Faith Berman Robert K. Brooner Howard B. Abikoff Boris Astrachan Robert Berman George W. Brown Lyn Y. Abramson Evelyn Attia Greg Berns Marty Bruce T. M. Achenbach S. Avenevoli Wade Berrettini Gerard E. Bruder Kenneth M. Adams Elizabeth Auchincloss Larry E. Beutler Maja Bucan Lawrence E.Adler David Avery Joseph Biederman Robert W. Buchanan Lenard A. Adler Thomas Babor Laura Bierut Kathleen K. Bucholz Nancy E. Adler Nadia Badawi George Bigelow Monte Buchsbaum Ralph Adolphs Alan D. Baddeley Robert Bilder Alan J. Budney George Aghajanian Lee Baer Rene Binder Stephen L. Buka W. Stewart Agras J. Michael Bailey Ray Bingham William E. Bunney Schahram Akbarian Ross J. Baldessarini Niels Birbaumer Audrey Burnam Huda Akil James C. Ballenger Boris Birmaher Barbara J. Burns Hagop S. Akiskal J. Bancroft Donald Black Terry Bush Claude Alain Karen J. Bandeen-Roche D. H. Blackwood Daniel Buysse Marigarita Alegria Deanna M. Barch Jack Blaine William Byne Georgios Alexopoulos John C. Barefoot Helen Blair Simpson Robert P. Cabaj Kimmo Alho Russell A. -

Why Ideal Epistemology? 2

1 Why Ideal Epistemology? 2 3 4 5 6 1 Ideal and nonideal epistemology 7 What are ideal and nonideal epistemology? We can begin by gesturing toward some loose sociological 8 trends: nonideal epistemology ideal epistemology informal, non-mathy formal, mathy1 talks about beliefs talks about credences2 emphasizes relation to emphasizes relation to decision knowledge theory uses “justified” uses “rational” uses “reasons” language doesn’t unimpressive babies superbabies written in Word written in LaTeX . 9 10 Ideal epistemologists are concerned with questions about what perfectly rational, cognitively ide- 11 alized, computationally unlimited believers would believe. (Note: I use the term “belief” broadly for any 12 doxastic state, including binary belief, credences, comparative confidence, etc.; mutatis mutandis for 13 “believe” and “believer”.) Often this involves presupposing or defending epistemic norms that, arguably, 14 no actual humans can satisfy: norms mandating 15 logical omniscience; ◦ 1 Note that despite this trend, the ideal/nonideal distinction in epistemology is strictly orthogonal to the formal/informal distinction. Theorists of bounded rationality often pursue formal nonideal epistemology; I personally often do informal ideal epistemology. 2 Again, despite the trend, this distinction is orthogonal to the ideal/nonideal distinction: AGM models of belief revision are a form of ideal epistemology, for example (Alchourrón et al., 1985). And much of the bounded rationality literature focuses on credence. 1 1 consistency and closure of binary beliefs; ◦ 2 infinitely precise credences; ◦ 3 credences satisfying the Kolmogorov probability axioms; ◦ 4 updating by conditionalization; ◦ 5 immediate update (rather than temporally extended reasoning); ◦ 6 closure of doxastic attitudes under boolean operations; ◦ 3 7 ...and so on. -

Objectivity in the Feminist Philosophy of Science

OBJECTIVITY IN THE FEMINIST PHILOSOPHY OF SCIENCE DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requisites for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Karen Cordrick Haely, M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2003 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Louise M. Antony, Adviser Professor Donald C. Hubin _______________________ Professor George Pappas Adviser Philosophy Graduate Program ABSTRACT According to a familiar though naïve conception, science is a rigorously neutral enterprise, free from social and cultural influence, but more sophisticated philosophical views about science have revealed that cultural and personal interests and values are ubiquitous in scientific practice, and thus ought not be ignored when attempting to understand, describe and prescribe proper behavior for the practice of science. Indeed, many theorists have argued that cultural and personal interests and values must be present in science (and knowledge gathering in general) in order to make sense of the world. The concept of objectivity has been utilized in the philosophy of science (as well as in epistemology) as a way to discuss and explore the various types of social and cultural influence that operate in science. The concept has also served as the focus of debates about just how much neutrality we can or should expect in science. This thesis examines feminist ideas regarding how to revise and enrich the concept of objectivity, and how these suggestions help achieve both feminist and scientific goals. Feminists offer us warnings about “idealized” concepts of objectivity, and suggest that power can play a crucial role in determining which research programs get labeled “objective”. -

Feminism & Philosophy Vol.5 No.1

APA Newsletters Volume 05, Number 1 Fall 2005 NEWSLETTER ON FEMINISM AND PHILOSOPHY FROM THE EDITOR, SALLY J. SCHOLZ NEWS FROM THE COMMITTEE ON THE STATUS OF WOMEN, ROSEMARIE TONG ARTICLES MARILYN FISCHER “Feminism and the Art of Interpretation: Or, Reading the First Wave to Think about the Second and Third Waves” JENNIFER PURVIS “A ‘Time’ for Change: Negotiating the Space of a Third Wave Political Moment” LAURIE CALHOUN “Feminism is a Humanism” LOUISE ANTONY “When is Philosophy Feminist?” ANN FERGUSON “Is Feminist Philosophy Still Philosophy?” OFELIA SCHUTTE “Feminist Ethics and Transnational Injustice: Two Methodological Suggestions” JEFFREY A. GAUTHIER “Feminism and Philosophy: Getting It and Getting It Right” SARA BEARDSWORTH “A French Feminism” © 2005 by The American Philosophical Association ISSN: 1067-9464 BOOK REVIEWS Robin Fiore and Hilde Lindemann Nelson: Recognition, Responsibility, and Rights: Feminist Ethics and Social Theory REVIEWED BY CHRISTINE M. KOGGEL Diana Tietjens Meyers: Being Yourself: Essays on Identity, Action, and Social Life REVIEWED BY CHERYL L. HUGHES Beth Kiyoko Jamieson: Real Choices: Feminism, Freedom, and the Limits of the Law REVIEWED BY ZAHRA MEGHANI Alan Soble: The Philosophy of Sex: Contemporary Readings REVIEWED BY KATHRYN J. NORLOCK Penny Florence: Sexed Universals in Contemporary Art REVIEWED BY TANYA M. LOUGHEAD CONTRIBUTORS ANNOUNCEMENTS APA NEWSLETTER ON Feminism and Philosophy Sally J. Scholz, Editor Fall 2005 Volume 05, Number 1 objective claims, Beardsworth demonstrates Kristeva’s ROM THE DITOR “maternal feminine” as “an experience that binds experience F E to experience” and refuses to be “turned into an abstraction.” Both reconfigure the ground of moral theory by highlighting the cultural bias or particularity encompassed in claims of Feminism, like philosophy, can be done in a variety of different objectivity or universality. -

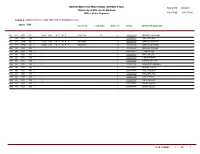

DEPARTMENT INSTRUCTIONAL REPORT-FINAL RUN DATE: 8/8/2008 University of Wisconsin-Madison Office of the Registrar RUN TIME: 9:43:37AM

DEPARTMENT INSTRUCTIONAL REPORT-FINAL RUN DATE: 8/8/2008 University of Wisconsin-Madison Office of the Registrar RUN TIME: 9:43:37AM SUBJECT: AGRICULTURAL AND APPLIED ECONOMICS (108) TERM: 1086 FACILITY_ID COMB_ENRL ENRL_TOT EMPLID INSTRUCTOR ROLE/NAME AGRICULTURALALS AND APPLIED ECONOMICS ACC 306 LEC 001 1 09:00 - 12:00 M T W R 0140 1185 49 6 0000875079 MICHAEL JOHNSON DJJ 399 IND 086 1 - 2 0000933523 PAUL MITCHELL ECC 875 SEM 001 2 13:00 - 16:00 M T W R F 0464 0B30 13 0002601604 MARVIN JOHNSON ECC 875 SEM 001 1 08:30 - 11:30 M T W R F 0464 0B30 13 0002601604 MARVIN JOHNSON DHH 990 IND 063 1 - 9 0000226384 MICHAEL CARTER DHH 990 IND 064 1 - 1 0002600175 THOMAS COX DHH 990 IND 073 1 - 3 0002601457 IAN COXHEAD DHH 990 IND 078 1 - 3 0002602152 T FORTENBERY DHH 990 IND 079 1 - 1 0002600972 STEVEN DELLER DHH 990 IND 080 1 - 3 0002602096 BRADFORD BARHAM DHH 990 IND 082 1 - 2 0000125075 JEREMY FOLTZ DHH 990 IND 083 1 - 6 0003374884 KYLE STIEGERT DHH 990 IND 086 1 - 1 0000933523 PAUL MITCHELL DHH 990 IND 087 1 - 3 0004111956 DAVID LEWIS DHH 990 IND 089 1 - 1 0001459007 SHI GUANMING DHH 990 IND 090 1 - 1 0001016452 BRENT HUETH DHH 999 IND 085 1 - 1 0003088634 BRIAN GOULD PAGE NUMBER: 1 OF 1 DEPARTMENT INSTRUCTIONAL REPORT-FINAL RUN DATE: 8/8/2008 University of Wisconsin-Madison Office of the Registrar RUN TIME: 9:44:48AM SUBJECT: BIOLOGICAL SYSTEMS ENGINEERING (112) TERM: 1086 FACILITY_ID COMB_ENRL ENRL_TOT EMPLID INSTRUCTOR ROLE/NAME BIOLOGICAL SYSTEMS ENGINEERING DHH 399 IND 010 1 - 2 0000693634 DAVID BOHNHOFF DHH 399 IND 014 1 - 2 0000664097 -

Paul Grice, Philosopher and Linguist Other Books by Siobhan Chapman

Paul Grice, Philosopher and Linguist Other books by Siobhan Chapman ACCENT IN CONTEXT PHILOSOPHY FOR LINGUISTS Paul Grice, Philosopher and Linguist Siobhan Chapman © Siobhan Chapman 2005 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 2005 978-1-4039-0297-9 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4LP. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The author has asserted her right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2005 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS and 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010 Companies and representatives throughout the world PALGRAVE MACMILLAN is the global academic imprint of the Palgrave Macmillan division of St. Martin’s Press, LLC and of Palgrave Macmillan Ltd. Macmillan® is a registered trademark in the United States, United Kingdom and other countries. Palgrave is a registered trademark in the European Union and other countries. ISBN 978-0-230-20693-9 ISBN 978-0-230-00585-3 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/978023005853 This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. -

Martha Nussbaum

Martha Nussbaum EDUCATION 1964-1966 Wellesley College 1966-1967 New York University, School of the Arts 1967-1969 New York University, Washington Square College. B.A. 1969. 1969-1975 Harvard University, M.A. 1971, Ph.D. 1975 (Classical Philology) 1972-1975 Harvard University, Society of Fellows, Junior Fellow 1973-1974 St. Hugh's College, Oxford University: Honorary Member of Senior Common Room EMPLOYMENT 1999-- University of Chicago, Ernst Freund Distinguished Service Professor of Law and Ethics Appointed in Law School and Philosophy Department, 2012 -- Appointed in: Law School, Philosophy Department, and Divinity School, -2012 Associate Member, Classics Department (1995 -- ) Associate Member, Department of Political Science (2003 -- ) Associate Member, Divinity School, (2012 --) Member, Committee on Southern Asian Studies (Affiliate 1999 –2005, full Member 2006--) Board Member,, Center for Gender Studies 1999-2002 Board Member, Human Rights Program, 2002--; Co-Chair, 2007-8; Founder and Coordinator, Center for Comparative Constitutionalism, 2002 – 2007 (spring) Visiting Professor of Law and Classics, Harvard University 2004 (spring) Visiting Professor, Centre for Political Science, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, India 1996-1998 University of Chicago, Ernst Freund Professor of Law and Ethics (Appointed in Law School, Philosophy Department, and Divinity School, Associate in Classics) 1996 (spring) Oxford University, Weidenfeld Visiting Professor 1995-1996 University of Chicago, Professor of Law and Ethics (Appointed in Law School, -

Adventures in Higher Education, Happiness, and Mindfulness

University of Colorado Law School Colorado Law Scholarly Commons Articles Colorado Law Faculty Scholarship 2018 Adventures in Higher Education, Happiness, and Mindfulness Peter H. Huang University of Colorado Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.law.colorado.edu/articles Part of the Law and Economics Commons, Law and Psychology Commons, Legal Biography Commons, Legal Education Commons, and the Legal Profession Commons Citation Information Peter H. Huang, Adventures in Higher Education, Happiness, and Mindfulness, 7 BRIT. J. AM. LEGAL STUD. 425 (2018), available at https://scholar.law.colorado.edu/articles/1237. Copyright Statement Copyright protected. Use of materials from this collection beyond the exceptions provided for in the Fair Use and Educational Use clauses of the U.S. Copyright Law may violate federal law. Permission to publish or reproduce is required. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Colorado Law Faculty Scholarship at Colorado Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of Colorado Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Br. J. Am. Leg. Studies 7(2) (2018), DOI: 10.2478/bjals-2018-0008 Adventures in Higher Education, Happiness, And Mindfulness Peter H. Huang* ABSTRACT Spis treści This Article recounts my unique adventures in higher education, including being a Princeton University freshman mathematics major at age 14, Harvard University applied mathematics graduate student at age 17, economics and finance faculty at multiple schools, first-year law student at the University of Chicago, second- and third-year law student at Stanford University, and law faculty at multiple schools. -

Herbert Paul Grice 1913–1988

PAUL GRICE Copyright © The British Academy 2001 – all rights reserved Herbert Paul Grice 1913–1988 PAUL GRICE was born 15 March 1913 in Birmingham, the elder son of Herbert Grice, businessman and musician, and his wife, Mabel Felton, a schoolmistress. He died on 28 August 1988, in Berkeley, California. The salient facts of his career are easily stated. He was educated first at Clifton College, Bristol, where he was head boy and also distinguished in music and sports, and second, at Corpus Christi College, Oxford, where he was awarded first class honours in classical honour moderations (1933) and literae humaniores (1935) and of which he later became an honorary fellow (1988). After a year as assistant master at Rossall School, Lancashire, and then two years as Harmsworth Senior Scholar at Merton College, Oxford, he was appointed lecturer and in 1939 Fellow and tutor in philosophy at St John’s College, Oxford, and university lecturer in the sub-faculty of philosophy. He was elected a Fellow of the British Academy in 1966 and became an Honorary Fellow of St John’s in 1980. During the Second World War he served in the Royal Navy in the Atlantic theatre and then in Admiralty intelligence from 1940 to 1945. In 1942 he married Kathleen, daughter of George Watson, naval architect, and sister of Steven Watson, a St John’s colleague and historian. After the war he soon became known as a philosopher of great origin- ality and independence and was frequently invited to the United States where he held visiting appointments at Harvard, Brandeis, Stanford, and Cornell universities. -

Npp2013281.Pdf

Neuropsychopharmacology (2013) 38, S435–S593 & 2013 American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. All rights reserved 0893-133X/13 www.neuropsychopharmacology.org Poster Session III-Wednesday participants indicated their ongoing experience of the Wednesday, December 11, 2013 intensity of heartbeat and breathing sensations by rotating a dial. Discrimination was measured by a positive dial deflection above baseline during an infusion trial. Accuracy W2. Interoceptive Awareness in Meditators During was measured via maximum cross correlation between each Cardiorespiratory Deviations in Body Arousal subject’s dial ratings and their corresponding heart rate Sahib Khalsa*, David Rudrauf, Richard Davidson, response. After each infusion participants also traced the Daniel Tranel body locations where they had felt heartbeat sensations, on a manikin template. UCLA Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Results: Bolus isoproterenol infusions elicited equivalent Behavior, Los Angeles, California increases in heart rate in both groups (Repeated measures ANOVA; F(1, 5) ¼ 50.1, po0.0001). There were no signifi- Background: Attention directed towards internal body cant group (F(1, 28) ¼ 1.27, p ¼ 0.27) or group x dose sensations is commonly practiced in many meditation interactions (F(1, 5) ¼ 0.04, p ¼ 0.998). There were also no traditions, and is a core skill cultivated when learning group differences in adrenergic sensitivity as measured by mindfulness. This practice is commonly proposed to CD25 (dose required to elevate heart rate by 25 beats per -

Willis and the Virtuosi

Forum on Public Policy The Scientific Method through the Lens of Neuroscience; From Willis to Broad J. Lanier Burns, Professor, Research Professor of Theological Studies, Senior Professor of Systematic Theology, Dallas Theological Seminar Abstract: In an age of unprecedented scientific achievement, I argue that the neurosciences are poised to transform our perceptions about life on earth, and that collaboration is needed to exploit a vast body of knowledge for humanity’s benefit. The scientific method distinguishes science from the humanities and religion. It has evolved into a professional, specialized culture with a common language that has synthesized technological forces into an incomparable era in terms of power and potential to address persistent problems of life on earth. When Willis of Oxford initiated modern experimentation, ecclesial authorities held intellectuals accountable to traditional canons of belief. In our secularized age, science has ascended to dominance with its contributions to progress in virtually every field. I will develop this transition in three parts. First, modern experimentation on the brain emerged with Thomas Willis in the 17th Century. A conscientious Anglican, he postulated a “corporeal soul,” so that he could pursue cranial research. He belonged to a gifted circle of scientifically minded scholars, the Virtuosi, who assisted him with his Cerebri anatome. He coined a number of neurological terms, moved research from the traditional humoral theory to a structural emphasis, and has been remembered for the arterial structure at the base of the brain, the “Circle of Willis.” Second, the scientific method is briefly described as a foundation for understanding its development in neuroscience.