Jewish Language Education in History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jewish Community Advocacy in Canada

JEWISH COMMUNITY ADVOCACY IN CANADA As the advocacy arm of the Jewish Federations of Canada, the Centre for Israel and Jewish Affairs is a non-partisan organization that creates and implements strategies for the purpose of improving the quality of Jewish life in Canada and abroad, increasing support for Israel, and strengthening the Canada-Israel relationship. Previously, the Jewish community in Canada had been well served for decades by two primary advocacy organizations: Canadian Jewish Congress (CJC) and Canada-Israel Committee (CIC). Supported by the organized Jewish community through Jewish Federations of Canada – UIA, these agencies responded to the needs and reflected the consensus within the Canadian Jewish Community. Beginning in 2004, the Canadian Council for Israel and Jewish Advocacy (CIJA) served as the management umbrella for CJC and CIC and, with the establishment of the University Outreach Committee (UOC), worked to address growing needs on Canadian campuses. Until 2011, each organization was governed and directed by independent Boards of Directors and professional staff. In 2011, these separate bodies were consolidated into one comprehensive and streamlined structure, the Centre for Israel and Jewish Affairs, which has been designed as the single address for all advocacy issues of concern to Canadian Jewry. The new structure provides for a robust, cohesive, and dynamic organization to represent the aspirations of Jewish Canadians across the country. As a non-partisan organization, the Centre creates and implements strategies to improve the quality of Jewish life in Canada and abroad, advance the public policy interests of the Canadian Jewish community, enhance ties with Jewish communities around the world, and strengthen the Canada-Israel relationship to the benefit of both countries. -

3. the Montreal Jewish Community and the Holocaust by Max Beer

Curr Psychol DOI 10.1007/s12144-007-9017-3 The Montreal Jewish Community and the Holocaust Max Beer # Springer Science + Business Media, LLC 2007 Abstract In 1993 Hitler and the Nazi party came to power in Germany. At the same time, in Canada in general and in Montreal in particular, anti-Semitism was becoming more widespread. The Canadian Jewish Congress, as a result of the growing tension in Europe and the increase in anti-Semitism at home, was reborn in 1934 and became the authoritative voice of Canadian Jewry. During World War II the Nazis embarked on a campaign that resulted in the systematic extermination of millions of Jews. This article focuses on the Montreal Jewish community, its leadership, and their response to the fate of European Jewry. The study pays particular attention to the Canadian Jewish Congress which influenced the outlook of the community and its subsequent actions. As the war progressed, loyalty to Canada and support for the war effort became the overriding issues for the community and the leadership and concern for their European brethren faded into the background. Keywords Anti-Semitism . Holocaust . Montreal . Quebec . Canada . Bronfman . Uptowners . Downtowners . Congress . Caiserman The 1930s, with the devastating worldwide economic depression and the emergence of Nazism in Germany, set the stage for a war that would result in tens of millions of deaths and the mass extermination of Europe’s Jews. The decade marked a complete stoppage of Jewish immigration to Canada, an increase in anti-Semitism on the North American continent, and the revival of the Canadian Jewish Congress as the voice for the Canadian Jewish community. -

Research Guide to Holocaust-Related Holdings at Library and Archives Canada

Research guide to Holocaust-related holdings at Library and Archives Canada August 2013 Library and Archives Canada Table of Contents INTRODUCTION...................................................................................................... 4 LAC’S MANDATE ..................................................................................................... 5 CONDUCTING RESEARCH AT LAC ............................................................................ 5 HOW TO USE THIS GUIDE ........................................................................................................................................ 5 HOW TO USE LAC’S ONLINE SEARCH TOOLS ......................................................................................................... 5 LANGUAGE OF MATERIAL.......................................................................................................................................... 6 ACCESS CONDITIONS ............................................................................................................................................... 6 Government of Canada records ................................................................................................................ 7 Private records ................................................................................................................................................ 7 NAZI PERSECUTION OF THE JEWISH BEFORE THE SECOND WORLD WAR............... 7 GOVERNMENT AND PRIME MINISTERIAL RECORDS................................................................................................ -

Combating Anti-Semitism Submitted By

PC.DEL/523/07 6 June 2007 ENGLISH only OSCE CONFERENCE ON COMBATING DISCRIMINATION AND PROMOTING MUTUAL RESPECT AND UNDERSTANDING Follow-up to the Cordoba Conference on anti-Semitism and Other Forms of Intolerance Bucharest, 7 and 8 June 2007 Plenary Session 1: Combating anti-Semitism Submitted by: Canadian Jewish Congress Len Rudner June 7, 2007 My name is Len Rudner. I represent the Canadian Jewish Congress, a Canadian Non- Governmental Organization, where I am the National Director of Community Relations. The views I express today are those of my organization. Antisemitism, the hatred of Jews has persisted into the twenty-first century, confirming its dubious distinction of being the “oldest hatred.” More than 60 years ago, Theodor Adorno defined antisemitism as a “rumour about the Jews.” Sadly, the rumours persist. In earlier generations, Jews were seen either as agents of repression or the harbingers of despised modernity. They were despised for the role that they played in the status quo and feared for their role as agents of change. Capitalists and Communists. Clannish outsiders and insidious invaders of the established body politic. Defined as the quintessential “Other” they existed as chimera, present only in the minds of those who hated and feared them. They represented a challenge to the established order and a ready answer to those who found solace in a simple answer to the fundamental question of why the world unfolds as it does. Confronted by the Black Death of the fourteenth century or the AIDS epidemic of the twentieth century, the answer was always the same: the Jews are our misfortune. -

Canada: Jewish Family History Research Guide

Courtesy of the Ackman & Ziff Family Genealogy Institute Revised March 2012; Updates March 2013 Canada: Jewish Family History Research Guide Brief History The earliest Jewish community in Canada was established in 1759, when Jews were first officially permitted to reside in the country. The first congregation was founded in 1768 in Montreal. Jewish settlement was mainly confined to Montreal until the 1840’s, when Jewish settlers slowly began to spread throughout the country. Jewish immigration increased around the turn of the 20th century, as it did in the United States. Today, Jews make up approximately 1.2% of Canada’s population. Primary Records Library and Archives Canada Library and Archives Canada is the main source of primary records from the 18th to the 20th centuries. This repository contains a vast range of materials relevant to Canadian Jewish genealogical research, including but not limited to vital, cemetery, census, immigration, naturalization, mutual/immigrant aid society, synagogue, military, orphanage/adoption, land, and employment records, national and local Jewish newspapers, and city directories. Many record groups have been indexed and are searchable online at http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/lac-bac/search/anc?. However, please note that only some of the indexed record groups are digitized and viewable as images online. Major digitized collections include National Census (1851, 1871, 1881, 1891, 1901, & 1911), Canadian Naturalization (1915-1951), Quebec City Passenger Lists (1865-1900), Immigrants from the Russian -

Download Paper (PDF)

In the Shadow of the holocauSt the changing Image of German Jewry after 1945 Michael Brenner In the Shadow of the Holocaust The Changing Image of German Jewry after 1945 Michael Brenner INA LEVINE ANNUAL LECTURE 31 JANUARY 2008 The assertions, opinions, and conclusions in this occasional paper are those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect those of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. First Printing, August 2010 Copyright © 2010 by Michael Brenner THE INA LEVINE INVITATIONAL SCHOLAR AWARD, endowed by the William S. and Ina Levine Foundation of Phoenix, Arizona, enables the Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies to bring a distinguished scholar to the Museum each year to conduct innovative research on the Holocaust and to disseminate this work to the American public. The Ina Levine Invitational Scholar also leads seminars, lectures at universities in the United States, and serves as a resource for the Museum, educators, students, and the general public. At its first postwar congress, in Montreux, Switzerland, in July 1948, the political commission of the World Jewish Congress passed a resolution stressing ―the determination of the Jewish people never again to settle on the bloodstained soil of Germany.‖1 These words expressed world Jewry‘s widespread, almost unanimous feeling about the prospect of postwar Jewish life in Germany. And yet, sixty years later, Germany is the only country outside Israel with a rapidly growing Jewish community. Within the last fifteen years its Jewish community has quadrupled from 30,000 affiliated Jews to approximately 120,000, with at least another 50,000 unaffiliated Jews. How did this change come about? 2 • Michael Brenner It belongs to one of the ironies of history that Germany, whose death machine some Jews had just escaped, became a center for Jewish life in post-war Europe. -

Jewish Heritage Month CIJA Exhibition Sampler

JEWS: A CANADIAN STORY IN PICTURES INTRODUCTION Ships on foreign shores. Battlefields. Legislatures. Open prairies. Busy markets. Theatres. Playgrounds. Protests. As with all newcomers, uncertainty greeted Canada’s first Nonetheless, Jews worked hard to participate in all Jews, who were not always welcomed with open arms. aspects of Canadian life. Jewish communities grew At times, the government limited Jewish immigration and throughout Canada - from East to West and from the city there were Canadians who did not want to share cities, to the country. The photographs in this exhibit show slices towns, and neighbourhoods with the newly-arrived Jews. of Jewish life in Canada throughout our nation’s history: the first settlement, establishment of communities of all shapes and sizes, and activities that went beyond the community to influence Canada’s evolution as a country. ARRIVAL We cannot bring WHO WERE CANADA’s fIRST JEWS? WAVE AFTER WAVE Jews who came to Canada in the century and a half before confederation in 1867 settled Between 1881 and 1901, a time when thousands sought refuge in Canada from the violent throughout what was then known as Lower and Upper Canada. pogroms in their Eastern European homelands, Canada’s Jewish population increased from 2,443 all the Jews here, but to 16,401. Steamship agents arranged passage across the Atlantic Ocean to Pier 21 in Halifax The first Jews who were said to have come to Lower Canada may have been of Portuguese and some remained in the East. Others made but a brief stop there before settling in large cities like origin, in 1697. -

Annual Report 2008

Just call us Table of Contents a pillar of the Message from the Board Chair and CEO . 3 Pillar 1 — community. Collaborative Community Planning . 4 Pillar 2 — Jewish Federation strengthens Financial Resource Development . 6 our community through four Federation Annual Campaign . 7 pillars of support: Jewish Community Foundation . 9 Pillar 3 — Leadership Development . 10 PillAR 1 | Pillar 4 — Israel and Overseas Connections . 12 COLLaboRATIVE COMMUNITY PLANNING We work together with our partner agencies to Financials . 14 identify community needs, and strategically allocate Allocations . 16 financial resources for effective responses. Board of Directors and Committee Chairs . 17 PillAR 2 | FINANCIAL ReSOURce DE VELopmeNT Federation generates funds through the Annual Campaign and the Jewish Community Foundation’s endowment program to meet needs in our community, in Israel and around the world . PillAR 3 | LeadeRSHIP DEVELopmeNT Federation nurtures and prepares emerging leaders for their future roles within our community . PillAR 4 | ISRaeL AND OVERSeaS CONNecTIONS We foster and strengthen our community’s ties with Israel and other overseas communities. 2 JFGV 2008 ANNUAL REPORT Rising to the challenge It is no surprise or secret that 2008 was a challenging year on many fronts . We began the year celebrating a record achievement in the 2007 Annual Campaign of $7 5. million, but closed out our 2008 campaign with a 4% decline in the face of the economic downturn . We sang and danced last spring in celebration of Israel’s 60th anniversary, but rang out the year with Israel’s southern region under extensive rocket attacks before and during Operation Cast Lead. The downturn and its impact on our areas define our work. -

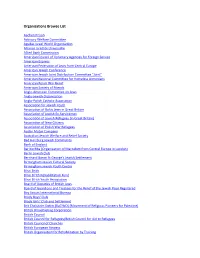

Organisations Browse List

Organisations Browse List Aachen Prison Advisory Welfare Committee Agudas Israel World Organisation Alliance Israélite Universelle Allied Bank Commission American Council of Voluntary Agencies for Foreign Service American Express American Federation of Jews from Central Europe American Jewish Conference American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee "Joint" American National Committee for Homeless Armenians American Polish War Relief American Society of Friends Anglo-American Committee on Jews Anglo-Jewish Organisation Anglo-Polish Catholic Association Association for Jewish Youth Association of Baltic Jews in Great Britain Association of Jewish Ex-Servicemen Association of Jewish Refugees (in Great Britain) Association of New Citizens Association of Polish War Refugees Austin Motor Company Australian Jewish Welfare and Relief Society Bad Harzburg Jewish Community Bank of England Bar Kochba (Organisation of Maccabim from Central Europe in London) Berlin Jewish Club Bernhard Baron St George's Jewish Settlement Birmingham Jewish Cultural Society Birmingham Jewish Youth Centre B'nai Brith B'nai B'rith Rehabilitation Fund B'nai B'rith Youth Association Board of Deputies of British Jews Board of Guardians and Trustees for the Relief of the Jewish Poor Registered Boy Scouts International Bureau Brady Boys' Club Brady Girls' Club and Settlement Brit Chalutzim Datim (BaCHaD) (Movement of Religious Pioneers for Palestine) British Broadcasting Corporation British Council British Council for Refugees/British Council for Aid to Refugees British Council -

The Six Percent Solution: an Analysis of Hate Legislation in Canada

The Six Percent Solution: An Analysis of Hate Legislation in Canada MARK SILVERBERG Executive Director, Pacific Region, Canadian Jewish Congress, Vancouver, B.C. Deepening hostility to Israel, an increase in potentially violent anti-Semitic incidents, the growing militancy of right-wing and left-wing extremist groups, the formation of an intellectual right with its racist ideas and the efforts to falsify history by denying the Holocaust—this is the face of the new anti-Semitism, the new Jewish condition in Canada. HE winds of discontent today, are ascertain the level and the extent of Tsweeping through the corridors of anti-Semitism and to measure the de power in Canada. They bring the gree to which it was either latent or wrath of a nation to a leadership too manifest. The results of the study are long indifferent, too apathetic and too generally favourable but the impact of distant from the needs of its minorities. its conclusions may well have a pro There is, in Canada today, a callous found effect upon the manner in which disregard for the realities and the man we perceive anti-Semitism in Canada. ifestations of hate. It is reflected in laws The study concludes that the major that are inadequate (and therefore ity of Canadians (over eighty percent) unenforceable) against purveyors of do not perceive Jews as being any dif hatred, who disseminate tape-recorded ferent from themselves. In short, over anti-Semitic sermons to their congre all attitudes towards Jews in Canada gants—with immunity; who speak of a are either positive or neutral as op world-wide Jewish conspiracy and of posed to negative. -

Jewish Archival Holdings in Canadailes Possessions Archiviques Juives Au Canada*

Janice Rosen JEWISH ARCHIVAL HOLDINGS IN CANADAILES POSSESSIONS ARCHIVIQUES JUIVES AU CANADA* Scholars interested in the Jewish experience in Canada are probably familiar with the riches of Archives in Canada. Few of the articles appearing in Canadian Jewish StudieslEtudes juives canadiennes could have been written without a visit to at least one institution housing archival records. Material about Jews in Canada can be found in archives across this country. "Jewish Archival Holdings" will be an ongoing section of CJSIEJC, providing descriptions of archival resources of interest to readers of this journal. In this first instalment, I survey the seven largest collections of Canadian Jewish archives in the country. In the future, I will profile other collections, as well as provide information on recent acquisitions. If you would like to see a particular collection discussed in an upcoming issue, please contact Janice Rosen, at the Canadian Jewish Congress National Archives, 1590ave Dr. Penfield, Montreal, Que. H3G 1C5, (514)931-7531. Les lecteurs de ce journal, les chercheurs int6ressCs aux Ctudes sur l 'histoire juive-canadienne, ne son t probablement pas Ctrangers au dornaine des archives du Canada Rares sont les articles apparaissant clans ce journal, qui ont6tCr6digCs sans avoirCtC prCca6s d'unevisite aupr8s d'une institution abritant des dossiers archiviques. 11 est possible de retrouver de ladocumentation concernant les Juifs 102 Janice Rosen du Canada, dans les archives h travers le pays. "Les possessions archiviques juives au Canada" constitue le premier d'une sCrie d'articles concernant la location de ressources archiviques, lesquels paraitront au MnCfice des lecteursdu CJSIEJC. Cepremier article fait 6tat des sept plus grosses collections d'archives juives-canadiennes au pays. -

Biblio-Ger-Jewish.Pdf

Abella, Irving M., and Harold Martin Troper. None Is Too Many : Canada and the Jews of Europe, 1933-1948. Toronto, Canada: Lester & Orpen Dennys, 1982. Belkin, Simon Isaiah, Canadian Jewish Congress., and Jewish Colonization Association. Through Narrow Gates; a Review of Jewish Immigration, Colonization and Immigrant Aid Work in Canada (1840-1940). Montreal,: Canadian Jewish Congress and the Jewish Colonization Association, 1966. Berdichewsky, Bernardo, and Canadian Jewish Congress. Pacific Region. Cultural Pluralism in Canada : What It Means to the Jewish Community. Vancouver: Canadian Jewish Congress Pacific Region, 1997. Brym, Robert J., William Shaffir, and Morton Weinfeld. The Jews in Canada. Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1993. Davids, Leo. "Yiddish in Canada: Picture and Prospects." Canadian Ethnic Studies 16, no. No. 2 (1984): 89-101. Diedger, Leo. ""Jewish Identity: Maintenance of Urban Religious and Ethnic Boundaries"." Ethnic and Racial Studies 3 (1980): 67-88. Diner, Hasia R. A Time for Gathering : The Second Migration, 1820-1880 Jewish People in America. V. 2. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992. Glanz, Rudolf. The Jewish Woman in America : Two Female Immigrant Generations, 1820-1929. New York: Ktav Pub. House, 1976. Goldstein, Alice. Determinants of Change and Response among Jews and Catholics in a Nineteenth Century German Village Jewish Social Studies Monograph Series. No. 3. New York: Conference on Jewish Social Studies : Distributed by Columbia University Press, 1984. Kage, Joseph. With Faith and Thanksgiving; the Story of Two Hundred Years of Jewish Immigration and Immigrant Aid Effort in Canada, 1760-1960. Montreal,: Eagle Pub. Co., 1962. Kloss, Heinz. ""Ein Paar Worte Ueber Das Jiddische in Kanada"." In Deutsch Als Muttersprache in Kanada: Berichte Zur Gegenwartslage, ed.