Evolution of Larval Forms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

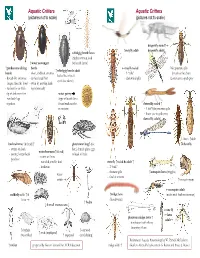

Aquatic Critters Aquatic Critters (Pictures Not to Scale) (Pictures Not to Scale)

Aquatic Critters Aquatic Critters (pictures not to scale) (pictures not to scale) dragonfly naiad↑ ↑ mayfly adult dragonfly adult↓ whirligig beetle larva (fairly common look ↑ water scavenger for beetle larvae) ↑ predaceous diving beetle mayfly naiad No apparent gills ↑ whirligig beetle adult beetle - short, clubbed antenna - 3 “tails” (breathes thru butt) - looks like it has 4 - thread-like antennae - surface head first - abdominal gills Lower jaw to grab prey eyes! (see above) longer than the head - swim by moving hind - surface for air with legs alternately tip of abdomen first water penny -row bklback legs (fbll(type of beetle larva together found under rocks damselfly naiad ↑ in streams - 3 leaf’-like posterior gills - lower jaw to grab prey damselfly adult↓ ←larva ↑adult backswimmer (& head) ↑ giant water bug↑ (toe dobsonfly - swims on back biter) female glues eggs water boatman↑(&head) - pointy, longer beak to back of male - swims on front -predator - rounded, smaller beak stonefly ↑naiad & adult ↑ -herbivore - 2 “tails” - thoracic gills ↑mosquito larva (wiggler) water - find in streams strider ↑mosquito pupa mosquito adult caddisfly adult ↑ & ↑midge larva (males with feather antennae) larva (bloodworm) ↑ hydra ↓ 4 small crustaceans ↓ crane fly ←larva phantom midge larva ↑ adult→ - translucent with silvery bflbuoyancy floats ↑ daphnia ↑ ostracod ↑ scud (amphipod) (water flea) ↑ copepod (seed shrimp) References: Aquatic Entomology by W. Patrick McCafferty ↑ rotifer prepared by Gwen Heistand for ACR Education midge adult ↑ Guide to Microlife by Kenneth G. Rainis and Bruce J. Russel 28 How do Aquatic Critters Get Their Air? Creeks are a lotic (flowing) systems as opposed to lentic (standing, i.e, pond) system. Look for … BREATHING IN AN AQUATIC ENVIRONMENT 1. -

Visceral and Cutaneous Larva Migrans PAUL C

Visceral and Cutaneous Larva Migrans PAUL C. BEAVER, Ph.D. AMONG ANIMALS in general there is a In the development of our concepts of larva II. wide variety of parasitic infections in migrans there have been four major steps. The which larval stages migrate through and some¬ first, of course, was the discovery by Kirby- times later reside in the tissues of the host with¬ Smith and his associates some 30 years ago of out developing into fully mature adults. When nematode larvae in the skin of patients with such parasites are found in human hosts, the creeping eruption in Jacksonville, Fla. (6). infection may be referred to as larva migrans This was followed immediately by experi¬ although definition of this term is becoming mental proof by numerous workers that the increasingly difficult. The organisms impli¬ larvae of A. braziliense readily penetrate the cated in infections of this type include certain human skin and produce severe, typical creep¬ species of arthropods, flatworms, and nema¬ ing eruption. todes, but more especially the nematodes. From a practical point of view these demon¬ As generally used, the term larva migrans strations were perhaps too conclusive in that refers particularly to the migration of dog and they encouraged the impression that A. brazil¬ cat hookworm larvae in the human skin (cu¬ iense was the only cause of creeping eruption, taneous larva migrans or creeping eruption) and detracted from equally conclusive demon¬ and the migration of dog and cat ascarids in strations that other species of nematode larvae the viscera (visceral larva migrans). In a still have the ability to produce similarly the pro¬ more restricted sense, the terms cutaneous larva gressive linear lesions characteristic of creep¬ migrans and visceral larva migrans are some¬ ing eruption. -

Evolution of Direct-Developing Larvae: Selection Vs Loss Margaret Snoke Smith,1 Kirk S

Hypotheses Evolution of direct-developing larvae: selection vs loss Margaret Snoke Smith,1 Kirk S. Zigler,2 and Rudolf A. Raff1,3* Summary echinoderms, sea urchins, reveal that a majority of sea urchin Observations of a sea urchin larvae show that most species exhibit one of two life history strategies (Fig. 1).(10) species adopt one of two life history strategies. One strategy is to make numerous small eggs, which develop One strategy is to make many small eggs that develop into a into a larva with a required feeding period in the water larva that must feed and grow for weeks or months in the water column before metamorphosis. In contrast, the second column before metamorphosis. In the water column, these strategy is to make fewer large eggs with a larva that does larvae are dependent on plankton abundance for food and are not feed, which reduces the time to metamorphosis and subject to high levels of predation.(11) The other strategy thus the time spent in the water column. The larvae associated with each strategy have distinct morpholo- involves increasing egg size and maternal provisioning, which gies and developmental processes that reflect their decreases the reliance on planktonic food sources and the feeding requirements, so that those that feed exhibit time to metamorphosis, thus minimizing larval mortality. indirect development with a complex larva, and those that However, assuming finite resources for egg production, do not feed form a morphologically simplified larva and increasing egg size also reduces the total number of eggs exhibit direct development. Phylogenetic studies show that, in sea urchins, a feeding larva, the pluteus, is the produced. -

Hookworm-Related Cutaneous Larva Migrans

326 Hookworm-Related Cutaneous Larva Migrans Patrick Hochedez , MD , and Eric Caumes , MD Département des Maladies Infectieuses et Tropicales, Hôpital Pitié-Salpêtrière, Paris, France DOI: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2007.00148.x Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jtm/article/14/5/326/1808671 by guest on 27 September 2021 utaneous larva migrans (CLM) is the most fre- Risk factors for developing HrCLM have specifi - Cquent travel-associated skin disease of tropical cally been investigated in one outbreak in Canadian origin. 1,2 This dermatosis fi rst described as CLM by tourists: less frequent use of protective footwear Lee in 1874 was later attributed to the subcutane- while walking on the beach was signifi cantly associ- ous migration of Ancylostoma larvae by White and ated with a higher risk of developing the disease, Dove in 1929. 3,4 Since then, this skin disease has also with a risk ratio of 4. Moreover, affected patients been called creeping eruption, creeping verminous were somewhat younger than unaffected travelers dermatitis, sand worm eruption, or plumber ’ s itch, (36.9 vs 41.2 yr, p = 0.014). There was no correla- which adds to the confusion. It has been suggested tion between the reported amount of time spent on to name this disease hookworm-related cutaneous the beach and the risk of developing CLM. Consid- larva migrans (HrCLM).5 ering animals in the neighborhood, 90% of the Although frequent, this tropical dermatosis is travelers in that study reported seeing cats on the not suffi ciently well known by Western physicians, beach and around the hotel area, and only 1.5% and this can delay diagnosis and effective treatment. -

Evolutionary Developmental Biology 573

EVOC20 29/08/2003 11:15 AM Page 572 Evolutionary 20 Developmental Biology volutionary developmental biology, now often known Eas “evo-devo,” is the study of the relation between evolution and development. The relation between evolution and development has been the subject of research for many years, and the chapter begins by looking at some classic ideas. However, the subject has been transformed in recent years as the genes that control development have begun to be identified. This chapter looks at how changes in these developmental genes, such as changes in their spatial or temporal expression in the embryo, are associated with changes in adult morphology. The origin of a set of genes controlling development may have opened up new and more flexible ways in which evolution could occur: life may have become more “evolvable.” EVOC20 29/08/2003 11:15 AM Page 573 CHAPTER 20 / Evolutionary Developmental Biology 573 20.1 Changes in development, and the genes controlling development, underlie morphological evolution Morphological structures, such as heads, legs, and tails, are produced in each individual organism by development. The organism begins life as a single cell. The organism grows by cell division, and the various cell types (bone cells, skin cells, and so on) are produced by differentiation within dividing cell lines. When one species evolves into Morphological evolution is driven another, with a changed morphological form, the developmental process must have by developmental evolution changed too. If the descendant species has longer legs, it is because the developmental process that produces legs has been accelerated, or extended over time. -

Insect Life Cycle ���������������������������������� a Reading A–Z Level L Leveled Book Word Count: 607

Insect Life Cycle A Reading A–Z Level L Leveled Book Word Count: 607 Written by Chuck Garofano Visit www.readinga-z.com www.readinga-z.com for thousands of books and materials. Photo Credits: Front cover, back cover, pages 3, 4, 7, 13, 15 (top): © Brand X Pictures; title page, page 11: © Kenneth Keifer/123RF; page 5: © Eric Isselée/ Dreamstime.com; page 6: © Mike Abbey/Visuals Unlimited, Inc.; page 8: © Richard Williams/123RF; page 9: © Oxford Scientific/Peter Arnold; page 10: © Anthony Bannister/Gallo Images/Corbis; page 12: © Dennis Johnson; Papillo/Corbis; page 14: © 123RF; page 15 (bottom): © ArtToday Written by Chuck Garofano Insect Life Cycle Level L Leveled Book Correlation © Learning A–Z LEVEL L Written by Chuck Garofano Fountas & Pinnell K All rights reserved. Reading Recovery 18 www.readinga-z.com www.readinga-z.com DRA 20 Table of Contents Flower beetle Introduction ................ 4 What Are Insects? ............ 6 Egg ....................... 8 Larva ......................10 Pupa ..................... 12 Ladybug Tropical ant Adult ..................... 13 Introduction Nymph . 14 When you were born, your body Index...................... 16 was shaped a lot like it is now. It was smaller, of course, but you had a head, legs, arms, and a torso. When you grow up, your body shape will be about the same. But some baby animals look nothing like the adults they will become. Insect Life Cycle • Level L 3 4 These animals have a different kind What Are Insects? of life cycle. A life cycle is the series There are more than 800,000 of changes an animal goes through different kinds of insects. -

POLYZOA (BRYOZOA) Sheet 107 ORDER CHEILOSTOMATA CYPHONAUTES LARVAE (BY J

CONSEIL INTERNATIONAL POUR L’EXPLORATION DE LA MER Zooplankton POLYZOA (BRYOZOA) Sheet 107 ORDER CHEILOSTOMATA CYPHONAUTES LARVAE (BY J. S. RYLAND) 1965 https://doi.org/10.17895/ices.pub.4948 Larvae found in the eastern North Atlantic c-2- lb ant. A post. lc la 4d 4e f If 12 4a 4c Plate I. Large cyphonautes with clear shells. 1. Membraniporu membranucea; a, lateral view (North Sea, July) ; b, apical view ((aresund, October) ; c, anterior view (as b) ; d, e, shell outlines of young larvae (Plymouth) ; f, g, variation in shell pro- file (North Sea, July). - 4. Electrapilosa (see also Plate 11); a, lateral view (Plymouth, December); b, apical view (Plymouth, January); c, anterior view (as b); d, e, shell outlines of young larvae (Plymouth). a.o., adhesive organ; f, flange; m, adductor muscle; P.o., pvriform organ; s., stomach. Scales = 200 ,U. All drawings except If, g to scale 1. (Id, e, 4d, e, after ATKINS,1955a; lb, c, f, g, 4b, c, from RYLAND,1964; la, 4a, original). -3- 4f 2b 5b - 2a a 0 0 cu - 5a - 6a 6b 3c 7b 3a 3d 7a Plate 11. Small cyphonautes with granular (particle-encrusted) shells. 2. Electra crustulenta; a, lateral view (Plymouth, January); b, apical view (as a). - 3. E. monostachys; a, lateral view (Plymouth, January); b, apical view (as a); c, shell profile of younger larva (Ply- mouth, January) ; d, lateral view (Burnham-on-Crouch, November). - 4. E. pilosa (see also Plate I) ; f-h, young larvae (Burnham-on-Crouch, November). - 5. Conopeum reticulum; a, lateral view (Burnham-on-Crouch, June) ; b, apical view (as a). -

Lists of Larval Worms from Marine Invertebrates of the Pacific Oc Ast of North America Hilda Lei Ching Hydra Enterprises

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UNL | Libraries University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications from the Harold W. Manter Parasitology, Harold W. Manter Laboratory of Laboratory of Parasitology 1991 Lists of Larval Worms from Marine Invertebrates of the Pacific oC ast of North America Hilda Lei Ching Hydra Enterprises Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/parasitologyfacpubs Part of the Aquaculture and Fisheries Commons, Biodiversity Commons, Other Animal Sciences Commons, Parasitology Commons, and the Zoology Commons Ching, Hilda Lei, "Lists of Larval Worms from Marine Invertebrates of the Pacific oC ast of North America" (1991). Faculty Publications from the Harold W. Manter Laboratory of Parasitology. 771. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/parasitologyfacpubs/771 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Parasitology, Harold W. Manter Laboratory of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications from the Harold W. Manter Laboratory of Parasitology by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Ching, Journal of the Helminthological Society of Washington (1991) 58(1). Copyright 1991, HELMSOC. Used by permission. J lIelminthol. Soc. Wash. 5'8(1). \ 991, pp. 57~8 Lists of Larval Worms from Marine Invertebrates of the Pacific Coast of North America HILDA LEI CHING Hydra Enterprises Ltd., P.O. Box 2184, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada V6B 3V7 ABS"fRAcr: Immature stages of 73 digenetic trematodes are listed by their families, marine invertebrate hosts, and localities and then cross listed according to their molluscan hosts. -

Larval Transport and Dispersal in the Coastal Ocean and Consequences for Population Connectivity

MARI N E P O P ULATIO N C O nn E C TI V ITY Larval Transport and Dispersal in the Coastal Ocean and Consequences for Population Connectivity BY JESÚS PI N E D A , J O N ATHA N A . H A R E , A nd S U Sp O N AUGLE MA N Y M ARI N E S P E C IES have small, pelagic early life stages. For those spe- cies, knowledge of population connectivity requires understanding the origin and trajectories of dispersing eggs and larvae among subpopulations. Researchers have used various terms to describe the movement of eggs and larvae in the marine envi- ronment, including larval dispersal, dispersion, drift, export, retention, and larval transport. Though these terms are intuitive and relevant for understanding the spatial dynamics of populations, some may be nonoperational (i.e., not measur- able), and the variety of descriptors and approaches used makes studies difficult to compare. Furthermore, the assumptions that underlie some of these concepts are rarely identified and tested. Here, we describe two phenomenologi- cally relevant concepts, larval transport and larval dispersal. These concepts have corresponding operational definitions, are relevant to understanding population connectivity, and have a long history in the literature, although they are sometimes confused and used interchangeably. After defin- ing and discussing larval transport and dispersal, we consider the relative importance of planktonic processes to the overall understanding and measurement of popula- tion connectivity. The ideas considered in this contribution are applicable to most benthic and pelagic species that undergo transforma- tions among life stages. -

Development of a Lecithotrophic Pilidium Larva Illustrates Convergent Evolution of Trochophore-Like Morphology Marie K

Hunt and Maslakova Frontiers in Zoology (2017) 14:7 DOI 10.1186/s12983-017-0189-x RESEARCH Open Access Development of a lecithotrophic pilidium larva illustrates convergent evolution of trochophore-like morphology Marie K. Hunt and Svetlana A. Maslakova* Abstract Background: The pilidium larva is an idiosyncrasy defining one clade of marine invertebrates, the Pilidiophora (Nemertea, Spiralia). Uniquely, in pilidial development, the juvenile worm forms from a series of isolated rudiments called imaginal discs, then erupts through and devours the larval body during catastrophic metamorphosis. A typical pilidium is planktotrophic and looks like a hat with earflaps, but pilidial diversity is much broader and includes several types of non-feeding pilidia. One of the most intriguing recently discovered types is the lecithotrophic pilidium nielseni of an undescribed species, Micrura sp. “dark” (Lineidae, Heteronemertea, Pilidiophora). The egg-shaped pilidium nielseni bears two transverse circumferential ciliary bands evoking the prototroch and telotroch of the trochophore larva found in some other spiralian phyla (e.g. annelids), but undergoes catastrophic metamorphosis similar to that of other pilidia. While it is clear that the resemblance to the trochophore is convergent, it is not clear how pilidium nielseni acquired this striking morphological similarity. Results: Here, using light and confocal microscopy, we describe the development of pilidium nielseni from fertilization to metamorphosis, and demonstrate that fundamental aspects of pilidial development are conserved. The juvenile forms via three pairs of imaginal discs and two unpaired rudiments inside a distinct larval epidermis, which is devoured by the juvenile during rapid metamorphosis. Pilidium nielseni even develops transient, reduced lobes and lappets in early stages, re-creating the hat-like appearance of a typical pilidium. -

Nemertea: the Ribbon Worms Kevin B

Nemertea: The Ribbon Worms Kevin B. Johnsan .d Nemerteans are an ancient pupof worms derived from the flat worms, Worldwide, there are about 800 species in the phylum Nemertea. They are found at all depths in the ocean, as well as in some freshwater and damp terrestrial habits, and a few species are commensals. Locally there are 39 species (Table 1). The nemerteans are chara-ed by soft, eIongate, and non- segmented bodies that are covered with cilia. Their bodies are highly contractile, a characteristic for whrch they are famous; intertidal species that when contracted are around 8 cm long can be 45 crn long when fully extended (Haderlie, 1980). Nemerteans are predators, capturing prey with a unique eversible proboscis that can be shot out to capture a victim. Reproduction and Development The phylum Nemertea dispIays a wide variety of repsoductive strategies. Many species are dioecious, though cases of hermaphroditism have been observed (Stricker, 1987). Although the ability to regenerate the body is common (e.g., Nusbaum and Oxner, 191 0,19111, asexual reproduction is not a norma1 past of the reproductive cycle for most nemerteans. Fertilization is often external. Eggs may either be spawned freely into the water column, protected in a gelatinous egg mass or other encasement, or, in a few instances, held internally by species that are ovovivipmous. The development of most nemerteans (orders Palaeo- nemertea, HopIonemertea, and Bdellonemertea) appears to be direct, with wormlike (vermiform) young developing in benthic egg cases before hatching.According to Stricker 11 98;3, vermifonn juveniIe nemerteans typically remain on the benthos after hatching, but some may spend a brief period in the plankton. -

The Importance of Larval Mollusca in the Plankton. by Marie V

335 Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/icesjms/article/8/3/335/730296 by guest on 01 October 2021 The Importance of Larval Mollusca in the Plankton. By Marie V. Lebour, Marine Biological Association, Plymouth. ITTLE was known about the biology of larval marine molluscs until quite recently, although a fair amount of scattered ' information may be found in the works of various authors, L 1 most of whom dealt with the eggs or newly hatched forms ). Their importance in the economy of the sea is very great. During the last few years the present writer has undertaken researches in the Plymouth Marine Laboratory with the object of investigating the planktonic molluscan larvae, the work so far dealing with the gastropods only. The results are astonishingly interesting, for not only have many elaborately formed and beautiful free-swimming larvae, hitherto unknown or undetermined, been identified with their adults, but many of them are found to occur in such numbers that they must influence considerably the general life of the plankton. They may do this in two ways. (1) They are wholly planktonic feeders and, in the veliger stage, with every movement they are taking into their bodies the nanno-plankton, chiefly diatoms, but also other minute organisms both animal and vegetable, thus competing to a large extent with the other plankton feeders. 1) References to these works are not given. The sign X after a name indicates that the observation is new but still unpublished, O indicating that the observation is not new but has been confirmed by the present writer.