Hookworm-Related Cutaneous Larva Migrans

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Literature Survey of Common Parasitic Zoonoses Encountered at Post-Mortem Examination in Slaughter Stocks in Tanzania: Economic and Public Health Implications

Volume 1- Issue 5 : 2017 DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2017.01.000419 Erick VG Komba. Biomed J Sci & Tech Res ISSN: 2574-1241 Research Article Open Access A Literature Survey of Common Parasitic Zoonoses Encountered at Post-Mortem Examination in Slaughter Stocks in Tanzania: Economic and Public Health Implications Erick VG Komba* Department of Veterinary Medicine and Public Health, Sokoine University of Agriculture, Tanzania Received: September 21, 2017; Published: October 06, 2017 *Corresponding author: Erick VG Komba, Senior lecturer, Department of Veterinary Medicine and Public Health, College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, Sokoine University of Agriculture, P.O. Box 3021, Morogoro, Tanzania Abstract Zoonoses caused by parasites constitute a large group of infectious diseases with varying host ranges and patterns of transmission. Their public health impact of such zoonoses warrants appropriate surveillance to obtain enough information that will provide inputs in the design anddistribution, implementation prevalence of control and transmission strategies. Apatterns need therefore are affected arises by to the regularly influence re-evaluate of both human the current and environmental status of zoonotic factors. diseases, The economic particularly and in view of new data available as a result of surveillance activities and the application of new technologies. Consequently this paper summarizes available information in Tanzania on parasitic zoonoses encountered in slaughter stocks during post-mortem examination at slaughter facilities. The occurrence, in slaughter stocks, of fasciola spp, Echinococcus granulosus (hydatid) cysts, Taenia saginata Cysts, Taenia solium Cysts and ascaris spp. have been reported by various researchers. Information on these parasitic diseases is presented in this paper as they are the most important ones encountered in slaughter stocks in the country. -

Gnathostoma Spinigerum Was Positive

Department Medicine Diagnostic Centre Swiss TPH Winter Symposium 2017 Helminth Infection – from Transmission to Control Sushi Worms – Diagnostic Challenges Beatrice Nickel Fish-borne helminth infections Consumption of raw or undercooked fish - Anisakis spp. infections - Gnathostoma spp. infections Case 1 • 32 year old man • Admitted to hospital with severe gastric pain • Abdominal pain below ribs since a week, vomiting • Low-grade fever • Physical examination: moderate abdominal tenderness • Laboratory results: mild leucocytosis • Patient revealed to have eaten sushi recently • Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was performed Carmo J, et al. BMJ Case Rep 2017. doi:10.1136/bcr-2016-218857 Case 1 Endoscopy revealed 2-3 cm long helminth Nematode firmly attached to / Endoscopic removal of larva with penetrating gastric mucosa a Roth net Carmo J, et al. BMJ Case Rep 2017. doi:10.1136/bcr-2016-218857 Anisakiasis Human parasitic infection of gastrointestinal tract by • herring worm, Anisakis spp. (A.simplex, A.physeteris) • cod worm, Pseudoterranova spp. (P. decipiens) Consumption of raw or undercooked seafood containing infectious larvae Highest incidence in countries where consumption of raw or marinated fish dishes are common: • Japan (sashimi, sushi) • Scandinavia (cod liver) • Netherlands (maatjes herrings) • Spain (anchovies) • South America (ceviche) Source: http://parasitewonders.blogspot.ch Life Cycle of Anisakis simplex (L1-L2 larvae) L3 larvae L2 larvae L3 larvae Source: Adapted to Audicana et al, TRENDS in Parasitology Vol.18 No. 1 January 2002 Symptoms Within few hours of ingestion, the larvae try to penetrate the gastric/intestinal wall • acute gastric pain or abdominal pain • low-grade fever • nausea, vomiting • allergic reaction possible, urticaria • local inflammation Invasion of the third-stage larvae into gut wall can lead to eosinophilic granuloma, ulcer or even perforation. -

The Functional Parasitic Worm Secretome: Mapping the Place of Onchocerca Volvulus Excretory Secretory Products

pathogens Review The Functional Parasitic Worm Secretome: Mapping the Place of Onchocerca volvulus Excretory Secretory Products Luc Vanhamme 1,*, Jacob Souopgui 1 , Stephen Ghogomu 2 and Ferdinand Ngale Njume 1,2 1 Department of Molecular Biology, Institute of Biology and Molecular Medicine, IBMM, Université Libre de Bruxelles, Rue des Professeurs Jeener et Brachet 12, 6041 Gosselies, Belgium; [email protected] (J.S.); [email protected] (F.N.N.) 2 Molecular and Cell Biology Laboratory, Biotechnology Unit, University of Buea, Buea P.O Box 63, Cameroon; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 28 October 2020; Accepted: 18 November 2020; Published: 23 November 2020 Abstract: Nematodes constitute a very successful phylum, especially in terms of parasitism. Inside their mammalian hosts, parasitic nematodes mainly dwell in the digestive tract (geohelminths) or in the vascular system (filariae). One of their main characteristics is their long sojourn inside the body where they are accessible to the immune system. Several strategies are used by parasites in order to counteract the immune attacks. One of them is the expression of molecules interfering with the function of the immune system. Excretory-secretory products (ESPs) pertain to this category. This is, however, not their only biological function, as they seem also involved in other mechanisms such as pathogenicity or parasitic cycle (molting, for example). Wewill mainly focus on filariae ESPs with an emphasis on data available regarding Onchocerca volvulus, but we will also refer to a few relevant/illustrative examples related to other worm categories when necessary (geohelminth nematodes, trematodes or cestodes). -

Genetic Characterization, Species Differentiation and Detection of Fasciola Spp

Ai et al. Parasites & Vectors 2011, 4:101 http://www.parasitesandvectors.com/content/4/1/101 REVIEW Open Access Genetic characterization, species differentiation and detection of Fasciola spp. by molecular approaches Lin Ai1,2,3†, Mu-Xin Chen1,2†, Samer Alasaad4, Hany M Elsheikha5, Juan Li3, Hai-Long Li3, Rui-Qing Lin3, Feng-Cai Zou6, Xing-Quan Zhu1,6,7* and Jia-Xu Chen2* Abstract Liver flukes belonging to the genus Fasciola are among the causes of foodborne diseases of parasitic etiology. These parasites cause significant public health problems and substantial economic losses to the livestock industry. Therefore, it is important to definitively characterize the Fasciola species. Current phenotypic techniques fail to reflect the full extent of the diversity of Fasciola spp. In this respect, the use of molecular techniques to identify and differentiate Fasciola spp. offer considerable advantages. The advent of a variety of molecular genetic techniques also provides a powerful method to elucidate many aspects of Fasciola biology, epidemiology, and genetics. However, the discriminatory power of these molecular methods varies, as does the speed and ease of performance and cost. There is a need for the development of new methods to identify the mechanisms underpinning the origin and maintenance of genetic variation within and among Fasciola populations. The increasing application of the current and new methods will yield a much improved understanding of Fasciola epidemiology and evolution as well as more effective means of parasite control. Herein, we provide an overview of the molecular techniques that are being used for the genetic characterization, detection and genotyping of Fasciola spp. -

Fasciola Hepatica and Associated Parasite, Dicrocoelium Dendriticum in Slaughter Houses in Anyigba, Kogi State, Nigeria

Advances in Infectious Diseases, 2018, 8, 1-9 http://www.scirp.org/journal/aid ISSN Online: 2164-2656 ISSN Print: 2164-2648 Fasciola hepatica and Associated Parasite, Dicrocoelium dendriticum in Slaughter Houses in Anyigba, Kogi State, Nigeria Florence Oyibo Iyaji1, Clement Ameh Yaro1,2*, Mercy Funmilayo Peter1, Agatha Eleojo Onoja Abutu3 1Department of Zoology and Environmental Biology, Faculty of Natural Sciences, Kogi State University, Anyigba, Nigeria 2Department of Zoology, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, Nigeria 3Department of Biology Education, Kogi State of Education Technical, Kabba, Nigeria How to cite this paper: Iyaji, F.O., Yaro, Abstract C.A., Peter, M.F. and Abutu, A.E.O. (2018) Fasciola hepatica and Associated Parasite, Fasciola hepatica is a parasite of clinical and veterinary importance which Dicrocoelium dendriticum in Slaughter causes fascioliasis that leads to reduction in milk and meat production. Bile Houses in Anyigba, Kogi State, Nigeria. samples were centrifuged at 1500 rpm for ten (10) minutes in a centrifuge Advances in Infectious Diseases, 8, 1-9. https://doi.org/10.4236/aid.2018.81001 machine and viewed microscopically to check for F. hepatica eggs. A total of 300 bile samples of cattle which included 155 males and 145 females were col- Received: July 20, 2016 lected from the abattoir. Results were analyzed using chi-square (p > 0.05). Accepted: January 16, 2018 The prevalence of F. gigantica and Dicrocoelium dentriticum is 33.0% (99) Published: January 19, 2018 and 39.0% (117) respectively. Age prevalence of F. hepatica revealed that 0 - 2 Copyright © 2018 by authors and years (33.7%, 29 cattle) were more infected than 2 - 4 years (32.7%, 70 cattle) Scientific Research Publishing Inc. -

Combination Anthelmintic Treatment for Persistent Ancylostoma Caninum Ova Shedding in Greyhounds

CASE SERIES Combination Anthelmintic Treatment for Persistent Ancylostoma caninum Ova Shedding in Greyhounds Lindie B. Hess, BS, Laurie M. Millward, DVM, Adam Rudinsky DVM, Emily Vincent, BS, Antoinette Marsh, PhD ABSTRACT Ancylostoma caninum is a nematode of the canine gastrointestinal tract commonly referred to as hookworm. This study involved eight privately owned adult greyhounds presenting with persistent A. caninum ova shedding despite previous deworming treatments. The dogs received a combination treatment protocol comprising topical moxidectin, followed by pyrantel/febantel/praziquantel within 24 hr. At 7–10 days posttreatment, a fecal examination monitored for parasite ova. Dogs remained on the monthly combination treatment protocol until they ceased shedding detectable ova. The dogs then received only the monthly topical moxidectin maintenance treatment. The dogs remained in the study for 5–14 mo with periodical fecal examinations performed. During the study, three dogs reverted to positive fecal ova status, with two being associated with client noncompliance. Reinstitution of the combination treatment protocol resulted in no detectable ova. Use of monthly doses of combination pyrantel, febantel and moxidectin appears to be an effective treatment for nonresponsive or persistent A. caninum ova shedding. Follow-up fecal examinations were important for verifying the presence or absence of ova shedding despite the use of anthelmintic treatment. Limitations of the current study include small sample size, inclusion of only privately owned greyhounds, and client compliance with fecal collection and animal care. (JAmAnimHospAssoc2019; 55:---–---. DOI 10.5326/ JAAHA-MS-6904) Introduction include the following: moxidectina,b, milbemycin oximec, fenben- Ancylostoma caninum is a nematode of the canine gastrointestinal dazoled, and/or pyrantel-containing productse,f. -

Dirofilaria Repens Nematode Infection with Microfilaremia in Traveler Returning to Belgium from Senegal

RESEARCH LETTERS 6. Sohan K, Cyrus CA. Ultrasonographic observations of the fetal We report human infection with a Dirofilaria repens nema- brain in the first 100 pregnant women with Zika virus infection in tode likely acquired in Senegal. An adult worm was extract- Trinidad and Tobago. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2017;139:278–83. ed from the right conjunctiva of the case-patient, and blood http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.12313 7. Parra-Saavedra M, Reefhuis J, Piraquive JP, Gilboa SM, microfilariae were detected, which led to an initial misdiag- Badell ML, Moore CA, et al. Serial head and brain imaging nosis of loiasis. We also observed the complete life cycle of of 17 fetuses with confirmed Zika virus infection in Colombia, a D. repens nematode in this patient. South America. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:207–12. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000002105 8. Kleber de Oliveira W, Cortez-Escalante J, De Oliveira WT, n October 14, 2016, a 76-year-old man from Belgium do Carmo GM, Henriques CM, Coelho GE, et al. Increase in Owas referred to the travel clinic at the Institute of Trop- reported prevalence of microcephaly in infants born to women ical Medicine (Antwerp, Belgium) because of suspected living in areas with confirmed Zika virus transmission during the first trimester of pregnancy—Brazil, 2015. MMWR Morb loiasis after a worm had been extracted from his right con- Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:242–7. http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/ junctiva in another hospital. Apart from stable, treated arte- mmwr.mm6509e2 rial hypertension and non–insulin-dependent diabetes, he 9. -

Molecular Identification of the Etiological Agent of Human

Jpn. J. Infect. Dis., 73, 44–50, 2020 Original Article Molecular Identification of the Etiological Agent of Human Gnathostomiasis in an Endemic Area of Mexico Sylvia Paz Díaz-Camacho1, Jesús Ricardo Parra-Unda2, Julián Ríos-Sicairos2, and Francisco Delgado-Vargas2* 1Research Unit in Environment and Health, Autonomous University of Occident, Sinaloa; and 2Public Health Research Unit "Dra. Kaethe Willms", School of Chemical and Biological Sciences, Autonomous University of Sinaloa, University city, Culiacan, Sinaloa, Mexico SUMMARY: Human gnathostomiasis, which is endemic in Mexico, is a worldwide health concern. It is mainly caused by the consumption of raw or insufficiently cooked fish containing the advanced third-stage larvae (AL3A) of Gnathostoma species. The diagnosis of gnathostomiasis is based on epidemiological surveys and immunological diagnostic tests. When a larva is recovered, the species can be identified by molecular techniques. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of the second internal transcription spacer (ITS-2) is useful to identify nematode species, including Gnathostoma species. This study aims to develop a duplex-PCR amplification method of the ITS-2 region to differentiate between the Gnathostoma binucleatum and G. turgidum parasites that coexist in the same endemic area, as well as to identify the Gnathostoma larvae recovered from the biopsies of two gnathostomiasis patients from Sinaloa, Mexico. The duplex PCR established based on the ITS- 2 sequence showed that the length of the amplicons was 321 bp for G. binucleatum and 226 bp for G. turgidum. The amplicons from the AL3A of both patients were 321 bp. Furthermore, the length and composition of these amplicons were identical to those deposited in GenBank as G. -

Proceedings of the Helminthological Society of Washington 51(2) 1984

Volume 51 July 1984 PROCEEDINGS ^ of of Washington '- f, V-i -: ;fx A semiannual journal of research devoted to Helminthohgy and all branches of Parasitology Supported in part by the -•>"""- v, H. Ransom Memorial 'Tryst Fund : CONTENTS -j<:'.:,! •</••• VV V,:'I,,--.. Y~v MEASURES, LENA N., AND Roy C. ANDERSON. Hybridization of Obeliscoides cuniculi r\ XGraybill, 1923) Graybill, ,1924 jand Obeliscoides,cuniculi multistriatus Measures and Anderson, 1983 .........:....... .., :....„......!"......... _ x. iXJ-v- 179 YATES, JON A., AND ROBERT C. LOWRIE, JR. Development of Yatesia hydrochoerus "•! (Nematoda: Filarioidea) to the Infective Stage in-Ixqdid Ticks r... 187 HUIZINGA, HARRY W., AND WILLARD O. GRANATH, JR. -Seasonal ^prevalence of. Chandlerellaquiscali (Onehocercidae: Filarioidea) in Braih, of the Common Grackle " '~. (Quiscdlus quisculd versicolor) '.'.. ;:,„..;.......„.;....• :..: „'.:„.'.J_^.4-~-~-~-<-.ii -, **-. 191 ^PLATT, THOMAS R. Evolution of the Elaphostrongylinae (Nematoda: Metastrongy- X. lojdfea: Protostrongylidae) Parasites of Cervids,(Mammalia) ...,., v.. 196 PLATT, THOMAS R., AND W. JM. SAMUEL. Modex of Entry of First-Stage Larvae ofr _^ ^ Parelaphostrongylus odocoilei^Nematoda: vMefastrongyloidea) into Four Species of Terrestrial Gastropods .....:;.. ....^:...... ./:... .; _.... ..,.....;. .-: 205 THRELFALL, WILLIAM, AND JUAN CARVAJAL. Heliconema pjammobatidus sp. n. (Nematoda: Physalbpteridae) from a Skate,> Psammobatis lima (Chondrichthyes: ; ''•• \^ Rajidae), Taken in Chile _... .„ ;,.....„.......„..,.......;. ,...^.J::...^..,....:.....~L.:....., -

Hookworm (Ancylostomiasis)

Hookworm (ancylostomiasis) Hookworm (ancylostomiasis) rev Jan 2018 BASIC EPIDEMIOLOGY Infectious Agent Hookworm is a soil transmitted helminth. Human infections are caused by the nematode parasites Necator americanus and Ancylostoma duodenale. Transmission Transmission primarily occurs via direct contact with fecal contaminated soil. Soil becomes contaminated with eggs shed in the feces of an individual infected with hookworm. The eggs must incubate in the soil for several days before they become infectious and are able to be transmitted to another person. Oral transmission can sometimes occur from consuming improperly washed food grown or exposed to fecal contaminated soil. Transmission can also occur (rarely) between a mother and her fetus/infant via infected placental or mammary tissue. Incubation Period Eggs must incubate in the soil for 5-10 days before they mature into infectious filariform larvae that can penetrate the skin. Within the first 10 days following penetration of the skin filariform larvae will migrate to the lungs and occasionally cause respiratory symptoms. Three to five weeks after skin penetration the larvae will migrate to the intestinal tract where they will mature into an adult worm. Adult worms may live in the intestine for 1-5 years depending on the species. Communicability Human to human transmission of hookworm does NOT occur because part of the worm’s life cycle must be completed in soil before becoming infectious. However, vertical transmission of dormant filariform larvae can occur between a mother and neonate via contaminated breast milk. These dormant filariform larvae can remain within in a host for months to years. Soil contamination is perpetuated by fecal contamination from infected individuals who can shed eggs in feces for several years after infection. -

Lecture 5: Emerging Parasitic Helminths Part 2: Tissue Nematodes

Readings-Nematodes • Ch. 11 (pp. 290, 291-93, 295 [box 11.1], 304 [box 11.2]) • Lecture 5: Emerging Parasitic Ch.14 (p. 375, 367 [table 14.1]) Helminths part 2: Tissue Nematodes Matt Tucker, M.S., MSPH [email protected] HSC4933 Emerging Infectious Diseases HSC4933. Emerging Infectious Diseases 2 Monsters Inside Me Learning Objectives • Toxocariasis, larva migrans (Toxocara canis, dog hookworm): • Understand how visceral larval migrans, cutaneous larval migrans, and ocular larval migrans can occur Background: • Know basic attributes of tissue nematodes and be able to distinguish http://animal.discovery.com/invertebrates/monsters-inside- these nematodes from each other and also from other types of me/toxocariasis-toxocara-roundworm/ nematodes • Understand life cycles of tissue nematodes, noting similarities and Videos: http://animal.discovery.com/videos/monsters-inside- significant difference me-toxocariasis.html • Know infective stages, various hosts involved in a particular cycle • Be familiar with diagnostic criteria, epidemiology, pathogenicity, http://animal.discovery.com/videos/monsters-inside-me- &treatment toxocara-parasite.html • Identify locations in world where certain parasites exist • Note drugs (always available) that are used to treat parasites • Describe factors of tissue nematodes that can make them emerging infectious diseases • Be familiar with Dracunculiasis and status of eradication HSC4933. Emerging Infectious Diseases 3 HSC4933. Emerging Infectious Diseases 4 Lecture 5: On the Menu Problems with other hookworms • Cutaneous larva migrans or Visceral Tissue Nematodes larva migrans • Hookworms of other animals • Cutaneous Larva Migrans frequently fail to penetrate the human dermis (and beyond). • Visceral Larva Migrans – Ancylostoma braziliense (most common- in Gulf Coast and tropics), • Gnathostoma spp. Ancylostoma caninum, Ancylostoma “creeping eruption” ceylanicum, • Trichinella spiralis • They migrate through the epidermis leaving typical tracks • Dracunculus medinensis • Eosinophilic enteritis-emerging problem in Australia HSC4933. -

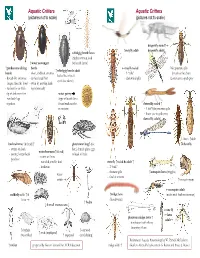

Aquatic Critters Aquatic Critters (Pictures Not to Scale) (Pictures Not to Scale)

Aquatic Critters Aquatic Critters (pictures not to scale) (pictures not to scale) dragonfly naiad↑ ↑ mayfly adult dragonfly adult↓ whirligig beetle larva (fairly common look ↑ water scavenger for beetle larvae) ↑ predaceous diving beetle mayfly naiad No apparent gills ↑ whirligig beetle adult beetle - short, clubbed antenna - 3 “tails” (breathes thru butt) - looks like it has 4 - thread-like antennae - surface head first - abdominal gills Lower jaw to grab prey eyes! (see above) longer than the head - swim by moving hind - surface for air with legs alternately tip of abdomen first water penny -row bklback legs (fbll(type of beetle larva together found under rocks damselfly naiad ↑ in streams - 3 leaf’-like posterior gills - lower jaw to grab prey damselfly adult↓ ←larva ↑adult backswimmer (& head) ↑ giant water bug↑ (toe dobsonfly - swims on back biter) female glues eggs water boatman↑(&head) - pointy, longer beak to back of male - swims on front -predator - rounded, smaller beak stonefly ↑naiad & adult ↑ -herbivore - 2 “tails” - thoracic gills ↑mosquito larva (wiggler) water - find in streams strider ↑mosquito pupa mosquito adult caddisfly adult ↑ & ↑midge larva (males with feather antennae) larva (bloodworm) ↑ hydra ↓ 4 small crustaceans ↓ crane fly ←larva phantom midge larva ↑ adult→ - translucent with silvery bflbuoyancy floats ↑ daphnia ↑ ostracod ↑ scud (amphipod) (water flea) ↑ copepod (seed shrimp) References: Aquatic Entomology by W. Patrick McCafferty ↑ rotifer prepared by Gwen Heistand for ACR Education midge adult ↑ Guide to Microlife by Kenneth G. Rainis and Bruce J. Russel 28 How do Aquatic Critters Get Their Air? Creeks are a lotic (flowing) systems as opposed to lentic (standing, i.e, pond) system. Look for … BREATHING IN AN AQUATIC ENVIRONMENT 1.