Sudan: Country Report – an Update

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Darfur Genocide

Darfur genocide Berkeley Model United Nations Welcome Letter Hi everyone! Welcome to the Darfur Historical Crisis committee. My name is Laura Nguyen and I will be your head chair for BMUN 69. This committee will take place from roughly 2006 to 2010. Although we will all be in the same physical chamber, you can imagine that committee is an amalgamation of peace conferences, UN meetings, private Janjaweed or SLM meetings, etc. with the goal of preventing the Darfur Genocide and ending the War in Darfur. To be honest, I was initially wary of choosing the genocide in Darfur as this committee’s topic; people in Darfur. I also understood that in order for this to be educationally stimulating for you all, some characters who committed atrocious war crimes had to be included in debate. That being said, I chose to move on with this topic because I trust you are all responsible and intelligent, and that you will treat Darfur with respect. The War in Darfur and the ensuing genocide are grim reminders of the violence that is easily born from intolerance. Equally regrettable are the in Africa and the Middle East are woefully inadequate for what Darfur truly needs. I hope that understanding those failures and engaging with the ways we could’ve avoided them helps you all grow and become better leaders and thinkers. My best advice for you is to get familiar with the historical processes by which ethnic brave, be creative, and have fun! A little bit about me (she/her) — I’m currently a third-year at Cal majoring in Sociology and minoring in Data Science. -

South West of Sudan and North-East South-Sudan - OCBA Projects KHARTOUM NORTH SHENDI 16°0'0"N KARARI Khartum, Sudan EPP

SOUDAN - South West of Sudan and North-East South-Sudan - OCBA projects KHARTOUM NORTH SHENDI 16°0'0"N KARARI Khartum, Sudan EPP Nile Project UMM BADDA Cell: OC5 SHARQ EL NILE Project code: ESSD160 Omdurman Dates: 1/1/2016 - 31/12/2017 Khartoum UM DURMAN KHARTOUM EL BUTANA Khartoum, capital JABAL El Bahr e Coordination AULIA l Azra JEBRAT EL q SHEIKH Cell: OC5 Project code: ESSD101 EL KAMLEEN Dates: 30/4/2017 - 31/1272017 El Kamlin SODARI EASTERN EL GEZIRA El Qutainah EL HASAHEESA Rufa'ah Hamrat El El Hasahisa Jebrat El Sheikh EL Sheikh EL GAZIRA MALHA NORTH KORDOFAN UMM RAMTTA UM EL QURA Sodari GREATER EL GUTAINA WAD MADANI El Managil EL MANAGEEL SOUTHERN EL GEZIRA BARA Ad Duwaym 14°0'0"N EL DOUIEM NORTH DARFUR EASTERN Bara SENNAR Sennar UMM KEDDADA EL NEHOUD SENNAR RABAK SENNAR Kosti SINGA UM RAWABA KOSTI Khor Waral, Arrivals SHIEKAN Tandalti Project WAD BANDA Cell: OC5 ABU ZABAD Umm Rawaba TENDALTI Project code: ESSD184 WHITE NILE Dates: 20/4/2017 - 20/8/2017 El Rahad En Nehoud EL DALI ABU HOUJAR EL SALAM El Jebelain Dibebad EL JABALIAN AL QOZ Al Khashafa (White Nile), Displaced WEST KORDOFAN Abu Zabad Project Cell: OC5 Project code: ESSD112 Ghubaysh EL ABASSIYA Dates:1/1/2016 - 31/1272017 GHUBAYSH AL SUNUT Delling DILLING 12°0'0"N Habila RASHAD Dalami Rashad El Fula HABILA EL SALAM AL TADAMON Umm Heitan Abu Jubaiha Lagawa BLUE NILE El Buheimer LAGAWA REIF ASHARGI BABANUSA Heiban ABU JUBAIHA HEIBAN ADILA SOUTH Miri Juwa KORDOFAN KADUGLI BAU Umm Dorain Kologi Keilak UMM DUREIN AL BURAM Talodi NORTHERN UPPER ABYEI - Buram EL KURMUK MUGLAD -

Humanitarian Situation Report No. 19 Q3 2020 Highlights

Sudan Humanitarian Situation Report No. 19 Q3 2020 UNICEF and partners assess damage to communities in southern Khartoum. Sudan was significantly affected by heavy flooding this summer, destroying many homes and displacing families. @RESPECTMEDIA PlPl Reporting Period: July-September 2020 Highlights Situation in Numbers • Flash floods in several states and heavy rains in upriver countries caused the White and Blue Nile rivers to overflow, damaging households and in- 5.39 million frastructure. Almost 850,000 people have been directly affected and children in need of could be multiplied ten-fold as water and mosquito borne diseases devel- humanitarian assistance op as flood waters recede. 9.3 million • All educational institutions have remained closed since March due to people in need COVID-19 and term realignments and are now due to open again on the 22 November. 1 million • Peace talks between the Government of Sudan and the Sudan Revolu- internally displaced children tionary Front concluded following an agreement in Juba signed on 3 Oc- tober. This has consolidated humanitarian access to the majority of the 1.8 million Jebel Mara region at the heart of Darfur. internally displaced people 379,355 South Sudanese child refugees 729,530 South Sudanese refugees (Sudan HNO 2020) UNICEF Appeal 2020 US $147.1 million Funding Status (in US$) Funds Fundi received, ng $60M gap, $70M Carry- forward, $17M *This table shows % progress towards key targets as well as % funding available for each sector. Funding available includes funds received in the current year and carry-over from the previous year. 1 Funding Overview and Partnerships UNICEF’s 2020 Humanitarian Action for Children (HAC) appeal for Sudan requires US$147.11 million to address the new and protracted needs of the afflicted population. -

GENDER PROGRAMMATIC REVIEW Sudan Country Office

GENDER PROGRAMMATIC REVIEW Sudan Country Office This independent Gender Review of the Country Programme of Cooperation Sudan-UNICEF 2013- 2017 is completed by the International Consultant: Mr Nagui Demian based in Canada matic Review UNICEF Sudan: Gender Programmatic Review Khartoum 7 July, 2017 FOREWORD The UNICEF Representative in Sudan, is pleased to present and communi- cate the final and comprehensive report of an independent gender pro- grammatic review for the country programme cycle 2013 – 2017. This review provides sounds evidence towards the progress made in Sudan in mainstreaming Gender-Based Programming and Accountability and measures the progress achieved in addressing gender inequalities. This ana- lytical report will serve as beneficial baseline for the Government, UNICEF and partners, among other stakeholders, to shape better design and priori- tisation of gender-sensitive strategies and approaches of the new country programme of cooperation 2018-2021 that will accelerate contributions to positive changes towards Goal 5 of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) on gender equality in Sudan. The objective of the gender review was to assess the extent to which UNICEF and partners have focused on gender-sensitive programming in terms of the priorities of the Sudan’s Country Programme, financial invest- ments, key results, lessons learnt and challenges vis-à-vis the four global priorities of UNICEF’s Gender Action Plan 2014-2017. We thank all sector line ministries at federal and state levels, UN agencies, local authorities, communities and our wide range of partners for their roles during the implementation of this review. In light of the above, we encourage all policy makers, UN agencies and de- velopment partners to join efforts to ensure better design and prioritisation of gender-sensitive strategies and approaches that will accelerate the posi- tive changes towards the Goal 5 of the SDGs and national priorities related to gender equality in Sudan. -

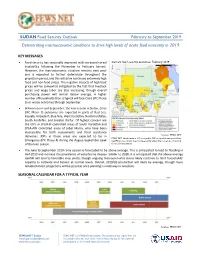

Sudan Food Security Outlook Report

SUDAN Food Security Outlook February to September 2019 Deteriorating macroeconomic conditions to drive high levels of acute food insecurity in 2019 KEY MESSAGES • Food security has seasonally improved with increased cereal Current food security outcomes, February 2019 availability following the November to February harvest. However, the macroeconomic situation remains very poor and is expected to further deteriorate throughout the projection period, and this will drive continued extremely high food and non-food prices. The negative impacts of high food prices will be somewhat mitigated by the fact that livestock prices and wage labor are also increasing, though overall purchasing power will remain below average. A higher number of households than is typical will face Crisis (IPC Phase 3) or worse outcomes through September. • Between June and September, the lean season in Sudan, Crisis (IPC Phase 3) outcomes are expected in parts of Red Sea, Kassala, Al Gadarif, Blue Nile, West Kordofan, North Kordofan, South Kordofan, and Greater Darfur. Of highest concern are the IDPs in SPLM-N controlled areas of South Kordofan and SPLA-AW controlled areas of Jebel Marra, who have been inaccessible for both assessments and food assistance deliveries. IDPs in these areas are expected to be in Source: FEWS NET FEWS NET classification is IPC-compatible. IPC-compatible analysis follows Emergency (IPC Phase 4) during the August-September peak key IPC protocols but does not necessarily reflect the consensus of national of the lean season. food security partners. • The June to September 2019 rainy season is forecasted to be above average. This is anticipated to lead to flooding in mid-2019 and increase the prevalence of waterborne disease. -

Sudan's Spreading Conflict (II): War in Blue Nile

Sudan’s Spreading Conflict (II): War in Blue Nile Africa Report N°204 | 18 June 2013 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i Recommendations..................................................................................................................... iii I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. A Sudan in Miniature ....................................................................................................... 3 A. Old-Timers Versus Newcomers ................................................................................. 3 B. A History of Land Grabbing and Exploitation .......................................................... 5 C. Twenty Years of War in Blue Nile (1985-2005) ........................................................ 7 III. Failure of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement ............................................................. 9 A. The Only State with an Opposition Governor (2007-2011) ...................................... 9 B. The 2010 Disputed Elections ..................................................................................... 9 C. Failed Popular Consultations ................................................................................... -

SUDAN Livelihood Profiles, North Kordofan State August 2013

SUDAN Livelihood Profiles, North Kordofan State August 2013 FEWS NET FEWS NET is a USAID-funded activity. The content of this report does Washington not necessarily reflect the view of the United States Agency for [email protected] International Development or the United States Government. www.fews.net SUDAN Livelihood Profiles, North Kordofan State August 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................................ 3 Acronyms and Abbreviations .................................................................................................................................. 4 Summary of Household Economy Approach Methodology ................................................................................... 5 The Household Economy Assessment in Sudan ..................................................................................................... 6 North Kordofan State Livelihood Profiling .............................................................................................................. 7 Overview of Rural Livelihoods in North Kordofan .................................................................................................. 8 Zone 1: Central Rainfed Millet and Sesame Agropastoral Zone (SD14) ............................................................... 10 Zone 2: Western Agropastoral Millet Zone (SD13) .............................................................................................. -

Sudan in Crisis

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Faculty Publications and Other Works by History: Faculty Publications and Other Works Department 7-2019 Sudan in Crisis Kim Searcy Loyola University Chicago, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/history_facpubs Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Searcy, Kim. Sudan in Crisis. Origins: Current Events in Historical Perspective, 12, 10: , 2019. Retrieved from Loyola eCommons, History: Faculty Publications and Other Works, This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications and Other Works by Department at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in History: Faculty Publications and Other Works by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. © Origins: Current Events in Historical Perspective, 2019. vol. 12, issue 10 - July 2019 Sudan in Crisis by Kim Searcy A celebration of South Sudan's independence in 2011. Editor's Note: Even as we go to press, the situation in Sudan continues to be fluid and dangerous. Mass demonstrations brought about the end of the 30-year regime of Sudan's brutal leader Omar al-Bashir. But what comes next for the Sudanese people is not at all certain. This month historian Kim Searcy explains how we got to this point by looking at the long legacy of colonialism in Sudan. Colonial rule, he argues, created rifts in Sudanese society that persist to this day and that continue to shape the political dynamics. -

Full Results of Survey of Songs

Existential Songs Full results Supplementary material for Mick Cooper’s Existential psychotherapy and counselling: Contributions to a pluralistic practice (Sage, 2015), Appendix. One of the great strengths of existential philosophy is that it stretches far beyond psychotherapy and counselling; into art, literature and many other forms of popular culture. This means that there are many – including films, novels and songs that convey the key messages of existentialism. These may be useful for trainees of existential therapy, and also as recommendations for clients to deepen an understanding of this way of seeing the world. In order to identify the most helpful resources, an online survey was conducted in the summer of 2014 to identify the key existential films, books and novels. Invites were sent out via email to existential training institutes and societies, and through social media. Participants were invited to nominate up to three of each art media that ‘most strongly communicate the core messages of existentialism’. In total, 119 people took part in the survey (i.e., gave one or more response). Approximately half were female (n = 57) and half were male (n = 56), with one of other gender. The average age was 47 years old (range 26–89). The participants were primarily distributed across the UK (n = 37), continental Europe (n = 34), North America (n = 24), Australia (n = 15) and Asia (n = 6). Around 90% of the respondents were either qualified therapists (n = 78) or in training (n = 26). Of these, around two-thirds (n = 69) considered themselves existential therapists, and one third (n = 32) did not. There were 235 nominations for the key existential song, with enormous variation across the different respondents. -

SUDAN Country Brief UNICEF Regional Study on Child Marriage in the Middle East and North Africa

SUDAN - Regional Study on Child Marriage 1 SUDAN Country Brief UNICEF Regional Study on Child Marriage In the Middle East and North Africa UNICEF Middle East and North Africa Regional Oce This report was developed in collaboration with the International Center for Research on Women (ICRW) and funded by the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). The views expressed and information contained in the report are not necessarily those of, or endorsed by, UNICEF. Acknowledgements The development of this report was a joint effort with UNICEF regional and country offices and partners, with contributions from UNFPA. Thanks to UNICEF and UNFPA Jordan, Lebanon, Yemen, Sudan, Morocco and Egypt Country and Regional Offices and their partners for their collaboration and crucial inputs to the development of the report. Proposed citation: ‘Child Marriage in the Middle East and North Africa – Sudan Country Brief’, United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) Middle East and North Africa Regional Office in collaboration with the International Center for Research on Women (IRCW), 2017. SUDAN - Regional Study on Child Marriage 3 4 SUDAN - Regional Study on Child Marriage SUDAN Regional Study on Child Marriage Key Recommendations Girls’ Voice and Agency Build capacity of women parliamentarians to effectively Provide financial incentives for sending girls raise and defend women-related issues in the parliament. to school through conditional cash transfers. Increase funding to NGOs for child marriage-specific programming. Household and Community Attitudes and Behaviours Engage receptive religious leaders through Legal Context dialogue and awareness workshops, and Coordinate advocacy efforts to end child marriage to link them to other organizations working on ensure the National Strategy is endorsed by the gov- child marriage, such as the Medical Council, ernment, and the Ministry of Justice completes its re- CEVAW and academic institutions. -

Hannah Peel Album PR-2

Hannah Peel Album: ‘Awake But Always Dreaming’ Label: My Own Pleasure Release date: Friday 23 September, 2016 Formats: Double Gatefold Vinyl LP (MOP04V), CD (MOP04CD) & Digital Download (MOPO4DD) “A great singer and a latter day Delia Derbyshire” The Observer “One to watch” The Independent “Hugely impressive” Drowned In Sound “Euphoric, orchestral pop” The Quietus “Hauntingly-beautiful, leviathan atmospheric pop” The Line Of Best Fit The Northern Irish artist and composer, Hannah Peel’s second solo album ‘Awake But Always Dreaming’ features 10 new songs including lead single ‘All That Matters’ plus a cover of Paul Buchanan’s ‘Cars In The Garden’ featuring a duet with Hayden Thorpe (Wild Beasts). Peel first came to recognition with her mesmerizing, hand-punched ‘music box’ EP ‘Rebox’, featuring co- vers of ‘80s bands Cocteau Twins, Soft Cell, & New Order. Having released her critically lauded solo de- but album ‘The Broken Wave’, Peel then formed The Magnetic North, a highly praised and expansive collaborative project with Simon Tong (The Verve, The Good The Bad And The Queen, Gorillaz) and Er- land Cooper (Erland & The Carnival). She also created a series of limited edition EPs, - the increasingly electronic ‘Nailhouse’ in 2013, followed by the stunning analogue beauty of ‘Fabricstate’ in 2014. A year later Peel released ‘Rebox 2’ with music-box covers of ‘Queen’ (originally performed by Perfume Genius), John Grant’s ‘Pale Green Ghosts’, Wild Beasts’ ‘Palace’, as well as her glorious cover of East India Youth’s triumphant ‘Heaven How Long’. 2016 has been yet another prolific year for Peel, so far including collaborations with Beyond The Wiz- ard’s Sleeve (aka Erol Alkan & Richard Norris) - she features on two BBC6 playlisted singles ‘Diagram Girl’ and ‘Creation’ - and composing under her new synth-based, space-age alter-ego Mary Casio with an experimental piece combining analogue electronics and a 33-piece colliery brass band (which debuted to a sold out Manchester audience in May). -

Measuring Up

Annual review 2016 The value we bring to media Measuring MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIR There are many positive testimonials to the work of the foundation over the years from the thousands of alumni who have benefited from our training. The most heartening compliment, repeated often, is that a Thomson Foundation course has been “a life-changing experience.” In an age, however, when funders want a more quantifiable impact, it is gratifying to have detailed external evidence of our achievements. Such is the case in Sudan (pages 10-13) where, over a four-year period, we helped to improve the quality of reporting of 700 journalists from print, radio and TV. An independent evaluation, led by a respected media development expert during 2016, showed that 98 per cent of participants felt the training had given them tangible benefits, including helping their career development. The evaluation also proved that a long-running training programme had helped to address systemic problems in a difficult regime, such as giving journalists the skills to minimise self-censorship and achieve international Measuring standards of reporting. Measuring the effectiveness of media development and journalism training courses has long been a contentious our impact issue. Sudan shows it is easier to do over the long term. As our digital training platform develops (pages 38-40), it will also be possible to measure the impact of a training in 2016 course in the short term. Our interactive programmes have been designed, and technology platform chosen, specifically so that real-time performance data for each user can be made easily available and progress measured.