Steve Jobs by Walter Isaacson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Steve Jobs' Diligence

Steve Jobs’ Diligence Full Lesson Plan COMPELLING QUESTION How can your diligence help you to be successful? VIRTUE Diligence DEFINITION Diligence is intrinsic energy for completing good work. LESSON OVERVIEW In this lesson, students will learn about Steve Jobs’ diligence in his life. They will also learn how to be diligent in their own lives. OBJECTIVES • Students will analyze Steve Jobs’ diligence throughout his life. • Students will apply their knowledge of diligence to their own lives. https://voicesofhistory.org BACKGROUND Steve Jobs was born in 1955. Jobs worked for video game company Atari, Inc. before starting Apple, Inc. with friend Steve Wozniak in 1976. Jobs and Wozniak worked together for many years to sell personal computers. Sales of the Macintosh desktop computer slumped, however, and Jobs was ousted from his position at Apple. Despite this failure, Jobs would continue to strive for success in the technology sector. His diligence helped him in developing many of the electronic devices that we use in our everyday life. VOCABULARY • Atari • Sojourn • Apple • Endeavor • NeXT • Contention • Pancreatic • Macintosh • Maternal • Pixar • Biological • Revolutionized • Tinkered INTRODUCE TEXT Have students read the background and narrative, keeping the Compelling Question in mind as they read. Then have them answer the remaining questions below. https://voicesofhistory.org WALK-IN-THE-SHOES QUESTIONS • As you read, imagine you are the protagonist. • What challenges are you facing? • What fears or concerns might you have? • What may prevent you from acting in the way you ought? OBSERVATION QUESTIONS • Who was Steve Jobs? • What was Steve Jobs’ purpose? • What diligent actions did Steve Jobs take in his life? • How did Steve Jobs help to promote freedom? DISCUSSION QUESTIONS Discuss the following questions with your students. -

Steve Wozniak Was Born in 1950 Steve Jobs in 1955, Both Attended Homestead High School, Los Altos, California

Steve Wozniak was born in 1950 Steve Jobs in 1955, both attended Homestead High School, Los Altos, California, Wozniak dropped out of Berkeley, took a job at Hewlett-Packard as an engineer. They met at HP in 1971. Jobs was 16 and Wozniak 21. 1975 Wozniak and Jobs in their garage working on early computer technologies Together, they built and sold a device called a “blue box.” It could hack AT&T’s long-distance network so that phone calls could be made for free. Jobs went to Oregon’s Reed College in 1972, quit in 1974, and took a job at Atari designing video games. 1974 Wozniak invited Jobs to join the ‘Homebrew Computer Club’ in Palo Alto, a group of electronics-enthusiasts who met at Stanford 1974 they began work on what would become the Apple I, essentially a circuit board, in Jobs’ bedroom. 1976 chiefly by Wozniak’s hand, they had a small, easy-to-use computer – smaller than a portable typewriter. In technical terms, this was the first single-board, microprocessor-based microcomputer (CPU, RAM, and basic textual-video chips) shown at the Homebrew Computer Club. An Apple I computer with a custom-built wood housing with keyboard. They took their new computer to the companies they were familiar with, Hewlett-Packard and Atari, but neither saw much demand for a “personal” computer. Jobs proposed that he and Wozniak start their own company to sell the devices. They agreed to go for it and set up shop in the Jobs’ family garage. Apple I A main circuit board with a tape-interface sold separately, could use a TV as the display system, text only. -

Apple Strategy Teardown

Apple Strategy Teardown The maverick of personal computing is looking for its next big thing in spaces like healthcare, AR, and autonomous cars, all while keeping its lead in consumer hardware. With an uphill battle in AI, slowing growth in smartphones, and its fingers in so many pies, can Apple reinvent itself for a third time? In many ways, Apple remains a company made in the image of Steve Jobs: iconoclastic and fiercely product focused. But today, Apple is at a crossroads. Under CEO Tim Cook, Apple’s ability to seize on emerging technology raises many new questions. Primarily, what’s next for Apple? Looking for the next wave, Apple is clearly expanding into augmented reality and wearables with the Apple Watch AirPods wireless headphones. Though delayed, Apple’s HomePod speaker system is poised to expand Siri’s footprint into the home and serve as a competitor to Amazon’s blockbuster Echo device and accompanying virtual assistant Alexa. But the next “big one” — a success and growth driver on the scale of the iPhone — has not yet been determined. Will it be augmented reality, healthcare, wearables? Or something else entirely? Apple is famously secretive, and a cloud of hearsay and gossip surrounds the company’s every move. Apple is believed to be working on augmented reality headsets, connected car software, transformative healthcare devices and apps, as well as smart home tech, and new machine learning applications. We dug through Apple’s trove of patents, acquisitions, earnings calls, recent product releases, and organizational structure for concrete hints at how the company will approach its next self-reinvention. -

A Day in the Life of Your Data

A Day in the Life of Your Data A Father-Daughter Day at the Playground April, 2021 “I believe people are smart and some people want to share more data than other people do. Ask them. Ask them every time. Make them tell you to stop asking them if they get tired of your asking them. Let them know precisely what you’re going to do with their data.” Steve Jobs All Things Digital Conference, 2010 Over the past decade, a large and opaque industry has been amassing increasing amounts of personal data.1,2 A complex ecosystem of websites, apps, social media companies, data brokers, and ad tech firms track users online and offline, harvesting their personal data. This data is pieced together, shared, aggregated, and used in real-time auctions, fueling a $227 billion-a-year industry.1 This occurs every day, as people go about their daily lives, often without their knowledge or permission.3,4 Let’s take a look at what this industry is able to learn about a father and daughter during an otherwise pleasant day at the park. Did you know? Trackers are embedded in Trackers are often embedded Data brokers collect and sell, apps you use every day: the in third-party code that helps license, or otherwise disclose average app has 6 trackers.3 developers build their apps. to third parties the personal The majority of popular Android By including trackers, developers information of particular individ- and iOS apps have embedded also allow third parties to collect uals with whom they do not have trackers.5,6,7 and link data you have shared a direct relationship.3 with them across different apps and with other data that has been collected about you. -

Apple Co-Founder Steve Wozniak Announced As Xtuple Conference Opener

Apple Co-Founder Steve Wozniak Announced as xTuple Conference Opener Open source software leader partners with oldest speakers' forum in the U.S. NORFOLK, VA - June 16, 2014 — xTuple CEO Ned Lilly announced today that pass-holders to the company’s “ultimate user conference” will enjoy the legendary Steve Wozniak, co-founder of Apple (http://www.woz.org/) , as opening VIP keynote speaker, thanks to a partnership with The Norfolk Forum (http://thenorfolkforum.org/) . Scheduled for Monday, October 13, through Saturday, October 18, #xTupleCon14 moves this year to the premier downtown Norfolk Marriott Waterside Hotel and Conference Center. Conference Opener: Tuesday, October 14, at Chrysler Hall, 7:30 p.m. Steve Wozniak, Apple Inc. Founder, Silicon Valley Icon and Philanthropist Steve Wozniak helped shape the computing industry with his design of Apple's first line of products – the Apple I and II – and influenced the popular Macintosh. In 1976, Wozniak and Steve Jobs founded Apple Computer, Inc., with Wozniak's Apple I personal computer. The following year, he introduced his Apple II personal computer, featuring a central processing unit, a keyboard, color graphics, and a floppy disk drive. The Apple II was integral in launching the personal computer industry Wozniak currently serves as Chief Scientist for the in-memory hardware company Fusion-io and is a published author with the release of his New York Times best-selling autobiography, iWoz: From Computer Geek to Cult Icon, in September 2006 by Norton Publishing. xTuple has a lifelong affiliation with Apple products, including desktops, MacBooks, iPhones and iPads. Users of xTuple ERP are three times more likely to be running Apple products than the average business user. -

Apple Tv: Guess What's in the Box

APPLE TV: GUESS WHAT'S IN THE BOX Jacob, Phil. The Daily Telegraph 10 Nov 2012: 46. Full Text THE TECHNOLOGY GIANT HAS ALREADY REVOLUTIONISED OUR LIVES. NOW IT IS SET TO CHANGE THE VERY CONCEPT OF TELEVISION, WRITES PHIL JACOB It's not a nice, simple story that Apple is going to come in and turn the world upside down and we'll all live happily ever after We live in a world where you use your iPhone to make calls, check your iPad for the news before going to work and sitting down in front of your iMac. Still haven't had your fill of Apple yet? Try downloading a song on iTunes before going for a run -- while listening to your iPod. Over the past 36 years, Apple has dominated and revolutionised our lives like no company in history. But the tech giant has perhaps its biggest revolution still waiting in the wings -- a complete and radical overhaul of the television industry. Speculation about an Apple TV has been rife since the publication of Steve Jobs' biography last year. The Apple co-founder, who died on October 5, 2011, told his biographer Walter Isaacson he had "cracked" the problem of television, although Isaacson did not reveal the plans as the product has not been launched. Late last year industry sources were quoted as saying that Apple would launch 81cm and 94cm TV sets some time this year. "Two people briefed on the matter said the technology involved could ultimately be embedded in a television," The Wall Street Journal reported. -

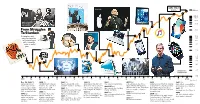

From Struggles to Stardom

AAPL 175.01 Steve Jobs 12/21/17 $200.0 100.0 80.0 17 60.0 Apple co-founders 14 Steve Wozniak 40.0 and Steve Jobs 16 From Struggles 10 20.0 9 To Stardom Jobs returns Following its volatile 11 10.0 8.0 early years, Apple has 12 enjoyed a prolonged 6.0 period of earnings 15 and stock market 5 4.0 gains. 2 7 2.0 1.0 1 0.8 4 13 1 6 0.6 8 0.4 0.2 3 Chart shown in logarithmic scale Tim Cook 0.1 1980 ’82 ’84 ’86’88 ’90 ’92 ’94 ’96 ’98 ’00 ’02 ’04 ’06’08 ’10 ’12 ’14 ’16 2018 Source: FactSet Dec. 12, 1980 (1) 1984 (3) 1993 (5) 1998 (8) 2003 2007 (12) 2011 2015 (16) Apple, best known The Macintosh computer Newton, a personal digital Apple debuts the iMac, an The iTunes store launches. Jobs announces the iPhone. Apple becomes the most valuable Apple Music, a subscription for the Apple II home launches, two days after assistant, launches, and flops. all-in-one desktop computer 2004-’05 (10) Apple releases the Apple TV publicly traded company, passing streaming service, launches. and iPod Touch, and changes its computer, goes public. Apple’s iconic 1984 1995 (6) with a colorful, translucent Apple unveils the iPod Mini, Exxon Mobil. Apple introduces 2017 (17 ) name from Apple Computer. Shares rise more than Super Bowl commercial. Microsoft introduces Windows body designed by Jony Ive. Shuffle, and Nano. the iPhone 4S with Siri. Tim Cook Introduction of the iPhone X. -

Steve Jobs: the Next Insanely Great Thing | WIRED

10/26/2020 Steve Jobs: The Next Insanely Great Thing | WIRED GARY WOLF 02.01.1996 12:00 PM Steve Jobs: The Next Insanely Great Thing Steve Jobs has been right twice. The first time we got Apple. The second time we got NeXT. The Macintosh ruled. NeXT tanked. STEVE JOBS HAS been right twice. The first time we got Apple. The second time we got NeXT. The Macintosh ruled. NeXT tanked. Still, Jobs was right both times. Although NeXT failed to sell its elegant and infamously buggy black box, Jobs's fundamental insight---that personal computers were destined to be connected to each other and live on networks---was just as accurate as his earlier prophecy that computers were destined to become personal appliances. Now Jobs is making a third guess about the future. His passion these days is for objects. Objects are software modules that can be combined into new applications (see "Get Ready for Web Objects"), much as pieces of Lego are built into toy houses. Jobs argues that objects are the key to keeping up with the exponential growth of the World Wide Web. And it's commerce, he says, that will fuel the next phase of the Web explosion. On a foggy morning last year, I drove down to the headquarters of NeXT Computer Inc. in Redwood City, California, to meet with Jobs. The building was quiet and immaculate, with that atmosphere of low-slung corporate luxury typical of successful Silicon Valley companies heading into their second decade. Ironically, NeXT is not a success. After burning through hundreds of millions of dollars from investors, the company abandoned the production of computers, focusing instead on the sale and development of its Nextstep operating system and on extensions into object-oriented technology. -

Apple Kicks Off Event; $1,000 Iphone Is Expected 12 September 2017, by Michael Liedtke and Barbara Ortutay

Apple kicks off event; $1,000 iPhone is expected 12 September 2017, by Michael Liedtke And Barbara Ortutay on him with joy instead of sadness." The souped-up "anniversary" iPhone, which would come a decade after Jobs unveiled the first version, could also cost twice what the original iPhone did. It would set a new price threshold for any smartphone intended to appeal to a mass market. WHAT A THOUSAND BUCKS WILL BUY Apple CEO Tim Cook kicks off the event for a new product announcement at the Steve Jobs Theater on the new Apple campus on Tuesday, Sept. 12, 2017, in Cupertino, Calif. (AP Photo/Marcio Jose Sanchez) Apple has kicked off a September product event at which it is expected to unveil a dramatically redesigned iPhone that could cost $1,000. With a photo of former Apple co-founder and CEO Steve It's the first product event Apple is holding at its Jobs projected in the background, Apple CEO Tim Cook new spaceship-like headquarters in Cupertino, kicks off the event for a new product announcement at California. Before getting to the new iPhone, the the Steve Jobs Theater on the new Apple campus, company unveiled a new Apple Watch model with Tuesday, Sept. 12, 2017, in Cupertino, Calif. (AP cellular service and an updated version of its Apple Photo/Marcio Jose Sanchez) TV streaming device. The event opened in a darkened auditorium, with only the audience's phones gleaming like stars, Various leaks have indicated the new phone will along with a message that said "Welcome to Steve feature a sharper display, a so-called OLED screen Jobs Theater." A voiceover from Jobs, Apple's co- that will extend from edge to edge of the device, founder who died in 2011, opened the event before thus eliminating the exterior gap, or "bezel," that CEO Tim Cook took stage. -

Effectively Communicating Y Ating Your Department's Worth

stayinging relrelevant Effectively communicatatinging yyour department’s worth Getting thee Cart before the Horse Stayinging ReRelevant Everythingng I lealearned about marketinarketing I learned from an Apple & the Circus Let’s talklk aboabout Apple Let’s Talkalk aboabout Apple 1976 - Steve Wozniak designs new computeruter (A(Apple I) & 21 year old Steve Jobs convinces him to take it commercial 1977 - Apple II becomes instant success 1980 - Apple sales soar to $1 million-a-yearear & ccompany goes public 1983 - John Sculley recruited to help buildld compcompany 1984 - Big Brother Superbowl ad 1985 - Jobs ousted by Sculley and board 1991 - Alliances with IBM and Motorola 1993 - Sculley ousted after handheld Newtonwton prproject fails 1984 SuperbSuperbowl Ad QuickTime™Time™ and a decompresompressor are needed to see ththis picture. Let’s Talkalk aboabout Apple 1976 - Steve Wozniak designs new computer (Apple 1) & 21 year old Steve Jobs convinces him to tak it commercial 1977 - Apple II becomes instant success 1980 - Apple sales soar to $1 million-a-year & compacompany goes public 1983 - John Sculley recruited to help build companypany 1984 - Big Brother Superbowl ad 1985 - Jobs ousted by Sculley and board 1991 - Alliances with IBM and Motorola 1993 - Sculley ousted after handheld Newton project fails 1996 - Apple acquires NeXT Software And then 1997 hhappened... QuickTime™Time™ and a decompreompressor are needed to see ththis picture. Communicatingicating the value Thinknk DiffeDifferent Marketing is about valulueses. This is a very complicated world. It's's a ververy noisy world. We' re not going to get a chanancece fofor people to remember a lot about us. No compapanyny isis. -

The History of Apple Inc

The History of Apple Inc. Veronica Holme-Harvey 2-4 History 12 Dale Martelli November 21st, 2018 Apple Inc is a multinational corporation that creates many different types of electronics, with a large chain of retail stores, “Apple Stores”. Their main product lines are the iPhone, iPad, and Macintosh computer. The company was founded by Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak and was created in 1977 in Cupertino, California. Apple Inc. is one of the world’s largest and most successful companies, recently being the first US company to hit a $1 trillion value. They shaped the way computers operate and look today, and, without them, numerous computer products that we know and love today would not exist. Although Apple is an extremely successful company today, they definitely did not start off this way. They have a long and complicated history, leading up to where they are now. Steve Jobs was one of the co-founders of Apple Inc. and one of first developers of the personal computer era. He was the CEO of Apple, and is what most people think of when they think ”the Apple founder”. Besides this, however, Steve Jobs was also later the chairman and majority shareholder of Pixar, and a member of The Walt Disney Company's board of directors after Pixar was bought out, and the founder, chairman, and CEO of NeXT. Jobs was born on February 24th, 1955 in San Francisco, California. He was raised by adoptive parents in Cupertino, California, located in what is now known as the Silicon Valley, and where the Apple headquarters is still located today. -

Ford Researchers Develop Technologies for an Aging Society

VOLUME 6 ISSUE 6 06/24/2012 Ford Researchers Develop Technologies for an Aging Society AACHEN, Germany, June 20, 2012 – Ford and improving the health and wellbeing may also be used to gain a better under- www.northbros.com Motor Company is developing a raft of of Ford’s customers. standing of mobility challenges faced by innovative technologies for an aging people of any age. society; these include a virtual reality The effectiveness and quality of vehicle More people die annually from cardiovas- CAVE (Cave Automatic Virtual Environ- interiors can now be tested long before ADS / COUPONS cular disease than from any other cause1. ment) which enables engineers to assess any new prototype model is actually Ford is developing a seat designed to the practicality of future interiors. built. Engineers observe the ease of detect cardiovascular problems and issue Engineers have also developed a “third driver and passenger interaction in a an advanced warning that may give the ORDER A PART age suit” to simulate restricted move- virtual reality environment called CAVE driver time to pull over. ment and dexterity, and a seat that can (Cave Automatic Virtual Environment). monitor a driver’s heart-rate and detect User-testing gauges the emotional re- The prototype seat employs electrocardio- irregularities. sponses of virtual drivers and passen- FORD SPECIALS graph (ECG) technology to monitor the “We’re not just a car company – we are gers to the virtual interior and this helps heart’s electrical impulses and detect also a ‘lifestyle enabler,’” said Sheryl engineers to fine-tune the layout to signs of irregularity that can provide an Connelly, manager, Global Trends and ensure the comfort of future occupants.