Migrant Rap in the Periphery Performing Politics of Belonging

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Moral Priorities of Rap Listeners

Published: Nzinga, K.L.K., & Medin, D.L. (2018). The Moral Priorities of Rap Listeners. Journal of Cognition and Culture, 312-342. http://booKsandjournals.brillonline.com/content/journals/10.1163/15685373-12340033 The Moral Priorities of Rap Listeners Kalonji L.K. NZINGA Douglas L. MEDIN Northwestern University A Cross-cultural approach to moral psychology starts from researchers withholding judgments about universal right and wrong and instead exploring community members’ values and what they subjeCtively perCeive to be moral or immoral in their loCal Context. This study seeks to identify the moral ConCerns that are most relevant to listeners of hip- hop music. We use validated psyChologiCal surveys inCluding the Moral Foundations Questionnaire (Graham, Haidt, & Nosek 2009) to assess whiCh moral ConCerns are most central to hip-hop listeners. Results show that hip-hop listeners prioritize concerns of justiCe and authentiCity more than non-listeners and deprioritize ConCerns about respeCting authority. These results show that the ConCept of the “good person” within the hip-hop subculture is fundamentally a person that is oriented towards soCial justiCe, rebellion against the status quo, and a deep devotion to keeping it real. Results are followed by a disCussion of the role that youth subCultures have in soCializing young people to prioritize Certain virtues over others as they develop their moral identity. 1. Introduction Many AmeriCan rappers inCluding KendriCk Lamar (2010), Snoop Dogg (2015), and Busta Rhymes (2006) have delivered the following CatCh phrase in their lyriCs: “You Can take me out the hood, but you Can’t take the hood out of me.” They proClaim that there are Certain aspeCts of the “hood” lifestyle and value system that, onCe they are part of you, direCt how you perCeive the world and behave in it. -

The Construction of Hip Hop Identities in Finnish Rap Lyrics Through English and Language Mixing

UNIVERSITY OF JYVÄSKYLÄ ”BUUZZIA, BUDIA JA HYVÄÄ GHETTOBOOTYA” - THE CONSTRUCTION OF HIP HOP IDENTITIES IN FINNISH RAP LYRICS THROUGH ENGLISH AND LANGUAGE MIXING A Pro Gradu Thesis in English by Elina Westinen Department of Languages 2007 HUMANISTINEN TIEDEKUNTA KIELTEN LAITOS Elina Westinen ”BUUZZIA, BUDIA JA HYVÄÄ GHETTOBOOTYA” - THE CONSTRUCTION OF HIP HOP IDENTITIES IN FINNISH RAP LYRICS THROUGH ENGLISH AND LANGUAGE MIXING Pro gradu –tutkielma Englannin kieli Joulukuu 2007 141 sivua Englannin kielen rooli ja asema maailmankielenä on kiistaton, ja Suomessakin englannin kieltä käytetään monilla eri aloilla. Juuriltaan amerikkalaisesta hip hop – kulttuuristakin on viime vuosina kasvanut globaali nuorisokulttuuri, joka on saavuttanut pysyvän aseman Suomessa. Tämän tutkimuksen tarkoituksena on selvittää, miten hip hop –identiteetti rakentuu suomalaisissa rap–lyriikoissa. Päätavoitteena on tutkia, millainen hip hop –identiteetti muodostuu lyriikoiden englannin kielen ja kielten sekoittumisen (suomi ja englanti) kautta. Tutkimuksen aineistona käytetään kolmen eri hip hop –artistin ja – ryhmän (Cheek, Sere & SP ja Kemmuru) lyriikoita 2000-luvulta. Niiden pääkieli on suomi, mutta kaikissa kappaleissa on myös englanninkielisiä elementtejä. Sanojen tarkkojen alkuperien sekä muun tiedon selvittämiseksi olen tarvittaessa konsultoinut itse artisteja. Analyysissä identiteetin käsitetään rakentuvan osaltaan kielen avulla. Identiteetti rakentuu diskursseissa, ja se on muuttuva ja monitahoinen. Aineiston analyysissä kielenvaihtelu ymmärretään joko a) kielten sekoittumisena, josta syntyy kokonaan uusi kieli/kielellinen tyyli tai b) koodinvaihtona, joka on merkityksellistä diskurssin paikallisella tasolla. Tulokset osoittavat, että rap–lyriikoissa pikemminkin sekoitetaan suomen ja englannin kieltä (language mixing) kuin vaihdetaan koodia. Näin ollen muodostuu uusi, suomalaisille rap–lyriikoille ominainen kieli ja tyyli. Usein hip hop -englannin sanoja ja fraaseja taivutetaan suomen ortografian, morfologian tai molempien mukaan. Joskus lyriikoissa esiintyy myös ns. -

January 2004 Issue of the SIX DEGREES-Magazine

FinlandsFinlands English English language language magazine magazine SixDegreesSixDegrees www.six-degrees.netwww.six-degrees.net IssueIssue 7/2003 1/2004 18.12.2003 28.1-24.2.2004 -27.1.2004 ������� ������ ������������������������������������������� � ������������������������������������������ ������������������������������������������������������ ��������������������������������������� ���������������������������������������������������� ������������������������������������������� ����������������������������������������������� ������������������������������������������� �������������������������������������������� ������������������������ ����������� �������� ���������� �������������������������������������������� ��������������������� ������������������������������������������� ����������� ������������ ������������������������������������������� ���������������� ������������������������������������������������ ������������������������������������������������ ����������������������������������������� ������������������������������������������� ����������������������������������������� ���������������������������� ���������������������������������������� ������������� ��������������������������������������������� ������������������������ �������� ���������������������������������������������� �������������������������������������� ������������������ �������������������� �������������� �������� ������������������������ ������������������ ��������������������� ����������� ��������� ������������������� ���� ������������ �������������� ����������������������� -

9Rgrou / F BT Expra6s

f- r n r:l I h. l_ i U ll tl L L. I I l--.- a I "bt" transeau t I : 'q a I I l ? kl I \ € 7 I \ 0 T a I I F II I , L r ^ I \ l t XI ?ortv 9rgrou / F BT expra6s... I \ .a 12 I ! ! I ./ J L. I tl I n I I I a 1 / T / t f I , t I I - \ \ \ ,/ 7 ll 7 / E t / / WWW.EIEH'I, ,1LL.EtrIM TICHTO RAP HOUSE REGGAE ROCK DAIiCEHATL ACIO IUI{GLE AMBIEI{T II{OUSTRIAI- BHAIiGRA FREESTYI"E SOUI. fUI{K R&B LATIII IiI,tR o 'AZZ o alternativelndusttiol . bhongro . blues . dub. freestyle . hi-nry / house. iozzvibes . jungle.latin. rop. reggoe/dancehall remix poradiso . rock . techno music & business: take o ride on the bt express... prem um music zine: print * web I tl v f! t) \ I ) , I t a , ) 1 1 I' ! t I I --l t I E l = ti _) http : / /www.streetso u n d.co m Eorror.rn.orrrr richdmrnrlil*'t^Ll'^fl-t##fhHffiJt**nurr,*r.ro* o,,,"oo, t)ag (IuExTED,ToRS: lonnld.msrAP.<Lry.s !g'f.mll:rin ($htiff) S P.lnnrle BoG TECtltO. r Todd "Lrh" BlGe T!(H. L.dh tdno.& *O(t. b f!t|rlc! Ht.tPG. ocrnc. rd tDtlOa-AI-tARGE. trtrl.t flodtE SoUL flJ N( R&B.Syu.li Houde aLrtRNATlVt. B.mrd io6lit G FREESIYLE . Rody lrp..t xtE jU . SEwTCES ?.d E. top.E JAZZ VIEES . Ri.l Edl.i NGIE Cl.rl.s lftGlyrn REGGAE Dlrc & T.ry D.hopo los HOUSE lnita E( vldta BHANGRA Iln Frhry / lcI sn€graour{D u( .woorba ( coxla rS um$ | M.td and uiai 6olg. -

'Bättre Folk' – Critical Sociolinguistic Commentary in Finnish Rap Music

Paper ‘Bättre folk’ – Critical Sociolinguistic Commentary in Finnish Rap Music by Elina Westinen (University of Jyväskylä) December 2011 ‘Bättre folk’ – Critical Sociolinguistic Commentary in Finnish Rap Music Elina Westinen Description Westinen, Elina, MA, is a doctoral student in the Center of Excellence for the Study of Variation, Contacts and Change in English (VARIENG), funded by the Academy of Finland (2006-2011) and in the Languages and Discourses in Social Media research team which is part of the Max Planck Working Group on Sociolinguistics and Superdiversity. In her ongoing PhD study, she is exploring the construction of polycentric authenticity in Finnish hip hop culture through linguistic and discursive repertoires on several scale-levels. Her research relates to the following research areas: sociolinguistics, discourse studies, multilingualism and hip hop research. Summary This paper discusses the ways in which rap music makes use of a range of resources to construct a critical sociolinguistic commentary. The specific case it focuses on is Finnish rap which takes issue with the official, but often tension-ridden Finnish-Swedish bilingualism in Finland. It shows how the resources used in this kind of rap are simultaneously discursive and linguistic and how they operate on several scale-levels, i.e. socio-temporal frames (Blommaert 2010), such as global, translocal and local. The findings of this paper will contribute to our understanding of (trans)local hip hop cultures and, more specifically, of the versatile nature of Finnish rap music. In my analysis, I will look into the ways in which a local rapper creates a sociolinguistic critique by making use of both discursive and linguistic resources. -

Helsinki Graffiti Subculture Meanings of Control and Gender in the Aftermath of Zero Tolerance

MALIN FRANSBERG Helsinki Grafti Subculture Meanings of Control and Gender in the Aftermath of Zero Tolerance Tampere University Dissertations 398 Tampere University Dissertations 398 MALIN FRANSBERG Helsinki Graffiti Subculture Meanings of Control and Gender in the Aftermath of Zero Tolerance ACADEMIC DISSERTATION To be presented, with the permission of the Faculty of Social Sciences of Tampere University, for public discussion in the lecture room K103 of the Linna, Kalevantie 5, 33014 Tampere, on 30th April, at 12 o’clock. ACADEMIC DISSERTATION Tampere University, Faculty of Social Sciences Finland Responsible Professor Päivi Honkatukia supervisor Tampere University Finland Pre-examiners Docent Tarja Tolonen Professor Keith Hayward University of Helsinki University of Copenhagen Finland Denmark Opponent Professor Shane Blackman Canterbury Christ Church University United Kingdom Custos Professor Turo-Kimmo Lehtonen Tampere University Finland The originality of this thesis has been checked using the Turnitin OriginalityCheck service. Copyright ©2021 Malin Fransberg Cover design: Roihu Inc. ISBN 978-952-03-1913-7 (print) ISBN 978-952-03-1914-4 (pdf) ISSN 2489-9860 (print) ISSN 2490-0028 (pdf) http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-03-1914-4 PunaMusta Oy – Yliopistopaino Joensuu 2021 Omistettu niille, jotka elivät nollatoleranssissa. iii iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Fifteen years ago, I could not have believed that I was about to start an academic career. For it was a cultural shock to attend the university as a young student in 2006. People there spoke in a different way, they were using strange words and manners that I was truly unfamiliar with. I often felt like an outsider because I did not know how to use academic jargon and those peculiar concepts that an intellectual language is so often demanded. -

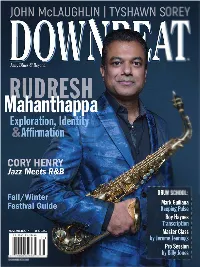

Chicago Jazz Festival Spotlights Hometown

NOVEMBER 2017 VOLUME 84 / NUMBER 11 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Managing Editor Brian Zimmerman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Markus Stuckey Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Hawkins Editorial Intern Izzy Yellen ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Kevin R. Maher 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Richard Seidel, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian, -

INKA RANTAKALLIO: New Spirituality, Atheism, and Authenticity in Finnish Underground Rap Doctoral Dissertation, 321 Pp

ANNALES UNIVERSITATIS TURKUENSIS UNIVERSITATIS ANNALES B 497 Inka Rantakallio NEW SPIRITUALITY, ATHEISM, AND AUTHENTICITY IN FINNISH UNDERGROUND RAP Inka Rantakallio Painosalama Oy, Turku, Finland 2019 Finland Turku, Oy, Painosalama ISBN 978-951-29-7864-9 (PRINT) – ISBN 978-951-29-7865-6 (PDF) TURUN YLIOPISTON JULKAISUJA ANNALES UNIVERSITATIS TURKUENSIS ISSN 0082-6987 (Print) SARJA - SER. B OSA - TOM. 497 | HUMANIORA | TURKU 2019 ISSN 2343-3191 (Online) NEW SPIRITUALITY, ATHEISM, AND AUTHENTICITY IN FINNISH UNDERGROUND RAP Inka Rantakallio TURUN YLIOPISTON JULKAISUJA – ANNALES UNIVERSITATIS TURKUENSIS SARJA - SER. B OSA – TOM. 497 | HUMANIORA | TURKU 2019 University of Turku Faculty of Humanities School of History, Culture and Arts Studies Department of Musicology Juno Doctoral programme Supervised by PhD, Senior Lecturer Susanna Välimäki PhD, Senior Lecturer Emeritus University of Turku Yrjö Heinonen University of Turku Professor John Richardson University of Turku PhD, Docent Siru Kainulainen PhD, Senior Lecturer Teemu Taira University of Turku University of Helsinki Reviewed by Professor Johannes Brusila PhD, Associate Professor Åbo Akademi University Christopher Driscoll Lehigh University Opponent Professor Johannes Brusila Åbo Akademi University The originality of this publication has been checked in accordance with the University of Turku quality assurance system using the Turnitin OriginalityCheck service. Cover Image: Sellekhanks ISBN 978-951-29-7864-9 (PRINT) ISBN 978-951-29-7865-6 (PDF) ISSN 0082-6987 (Print) ISSN 2343-3191 (Online) Painosalama Oy, Turku, Finland 2019 For the hip hop nation 3 UNIVERSITY OF TURKU Faculty of Humanities School of History, Culture and Arts Studies Musicology INKA RANTAKALLIO: New Spirituality, Atheism, and Authenticity in Finnish Underground Rap Doctoral Dissertation, 321 pp. -

Interdisciplines Journal of History and Sociology

InterDisciplines Journal of History and Sociology Volume 5 – Issue 1 Identities in Media and Music Case-studies from (Trans)national, Regional and Local Communities Editorial Board Alfons Bora (Bielefeld University) Jörg Bergmann (Bielefeld University) Thomas Welskopp (Bielefeld University) Peter Jelavich (Johns Hopkins University Baltimore) Kathleen Thelen (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) Volume 5 – Issue 1 Identities in Media and Music Case-studies from (Trans)national, Regional and Local Communities Guest editors Verena Molitor (Bielefeld) and Chiara Pierobon (Bielefeld) © 2014 by Bielefeld Graduate School in History and Sociology (BGHS) All rights reserved Managing editor: Sabine Schäfer (BGHS) Editorial assistant: Jenny Hahn (BGHS) Copy editor: Laura Radosh Layout: Anne C. Ware Cover picture by Chiara Pierobon (ZDES, Bielefeld University) Coverdesign: deteringdesign GmbH Bielefeld/Thomas Abel www.inter-disciplines.org www.uni-bielefeld.de/bghs ISSN 2191-6721 This publication was made possible by financial support from the German Research Foundation - Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG). This Special Issue was printed with support of the Center for German and European Studies (CGES/ZDES), sponsored by the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) by funds from the Federal Foreign Office. Contents Verena Molitor and Chiara Pierobon Introduction: »Identities in media and music. Case-studies from (trans)national, regional and local communities« .......................................... 1 Anna Wiehl The myth of European identity. Representation and construction of regional, national and European identities in German, French and international television news broadcasts ............................................... 13 Lieselotte Goessens This is the soundtrack of our identity: National mythscapes in music and the construction of collective identity through music in early Flemish radio (1929–1939) ............................................................... 51 Ulrike Thumberger Regional and national identity in Austrian dialectal pop songs. -

Antti-Ville Kärjä: Alkusoittoja

Antti-Ville Kärjä Alkusoittoja Musiikin menneisyydet monikulttuurisessa Suomessa SUOMEN ETNOMUSIKOLOGINEN SEURA, HELSINKI 2020 Kannen kuvat: Roolihahmoja Richard Straussin oopperassa Salome, 1900-luvun alku (HK19850504:3752), Historian kuvakokoelma, Museovirasto (CC BY 4.0). Áilu Valle, kuvaaja Ppntori, Wikimedia Commons (https://upload.wikimedia.org/ wikipedia/commons/6/61/Ailu_Valle.JPG; CC BY-SA 3.0). Sivunvalmistus: Tieteellisten seurain valtuuskunta Teoksen kirjoittamista ovat tukeneet Suomen tietokirjailijat ry sekä Musiikin edistämissäätiö. Teos perustuu Suomen Akatemian rahoittamaan tutkimustyöhön hankkeissa Populaarimusiikki jälkikoloniaalisessa Suomessa (129066) sekä Musiikki, monikulttuurisuus ja Suomi (265668, 282844, 304206). Suomen etnomusikologisen seuran julkaisuja 23. ISBN 978-952-99945-2-6 (nid.) ISBN 978-952-99945-3-3 (PDF) ISSN 0785-2746 Painettu: Grano, Vantaa 2020. Sisällys Aluksi ......................................................... 5 1 Johdanto .................................................... 7 Kansalaisten määrä ja laatu ...................................... 10 Etnomusikologia ja musiikinhistoria .............................. 15 Musiikin metahistoria ja jälkikoloniaalinen musiikinhistorian poliittisuus .................................................... 22 Suomen musiikin historia ja musiikinhistoria Suomessa Suomesta Suomelle ............................................. 30 2 Suomen musiikin historia ja musiikillinen orientalismi .......... 39 Orientti musiikissa ............................................ -

Kenyan Hip-Hop Artists' Theories of Multilingualism, Identity And

“HATUCHEKI NA WATU”: KENYAN HIP-HOP ARTISTS’ THEORIES OF MULTILINGUALISM, IDENTITY AND DECOLONIALITY By Esther Milu A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Rhetoric and Writing - Doctor of Philosophy 2016 ABSTRACT “HATUCHEKI NA WATU”: KENYAN HIP-HOP ARTISTS’ THEORIES OF MULTILINGUALISM, IDENTITY AND DECOLONIALITY By Esther Milu This is a qualitative research study that constellates several theoretical and methodological approaches to understand why and how three Kenyan Hip-hop artists, Jua Cali, Nazizi Hirji and Abbas Kubbaff, engage in translingual communicative practices. A variety of data types including in-depth phenomenologial interviews, lyrical content and multimodal compositions were evaluated to understand how and why the artists used particular linguistic and semiotic resources in composing their texts and in their everyday communication. A translingual analytical framework was applied to examine these resources across various modalities of communication: verbal, written, audio, visual, performative and embodied. Findings from the study indicate that the artists translingual practices are aimed at : 1) constructing various ethnicities and indentities based on their everyday language use and not on dominant language ideologies or theories of race and ethnicity in the country; 2) engaging in language activism work by raising critical language awareness within dominant institutions, and by actively participating in the preservation of youth languages and cultures; 3) theozing and practicing diverse options for cultural and linguistic decolonization. The study concludes by proposing a translingual pedagogy that challenges students to demonstrate critical awareness of the “linguistic culture” surrounding the languages, codes and symbolic practices they use in their translingual composing. -

Lorentz, Korinna

MASTERARBEIT im Studiengang Crossmedia Publishing & Management Erfolgversprechende Melodien – Analyse der Hooklines erfolgreicher Popsongs zur Erkennung von Mustern hinsichtlich der Aufeinanderfolge von Tönen und Tonlängen Vorgelegt von Korinna Gabriele Lorentz an der Hochschule der Medien Stuttgart am 08. Mai 2021 zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines „Master of Arts“ Erster Betreuer und Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Oliver Wiesener Zweiter Betreuer und Gutachter: Prof. Oliver Curdt E-Mail: [email protected] Matrikelnummer: 39708 Fachsemester: 4 Geburtsdatum, -ort: 15.04.1995 in Kiel Danksagung Mein größter Dank gilt Professor Dr. Oliver Wiesener für das Überlassen des Themas und die umfangreiche Unterstützung bei methodischen und stochastischen Überlegungen. Ich danke ihm insbesondere dafür, dass er trotz einiger anderer Betreuungsprojekte meine Masterarbeit angenommen hat und somit meinen Wunsch, im Musikbereich zu forschen, ermöglicht hat. Des Weiteren möchte ich meinem Freund und meiner Familie dafür danken, dass sie sich meine Problemstellungen bis zum Ende hin angehört haben und mir immer wieder Inspi- rationen für neue Lösungswege geben konnten. Besonderer Dank gilt meiner Mutter, Gabriele Lorentz, mit der ich interessante Gespräche zu musikalischen Themen führen konnte und mei- nem Vater, Dr. Thomas Lorentz, mit dem ich nächtliche Diskussionen über Markov-Ketten und Neuronale Netzwerke hatte. Ich danke meinen Eltern und meinem Freund, Michael Feuerlein, für die kritische Durchsicht der Arbeit. Kurzfassung In der vorliegenden Masterarbeit wurden die Melodie-Hooklines von Popsongs, die in Deutsch- land zwischen 1978 und 2019 sehr erfolgreich waren, explorativ analysiert. Ziel war, zu unter- suchen, ob gewisse Muster in den Reihenfolgen der Töne und Tonlängen vorkommen, und diese zu finden. Für die Mustersuche wurden Markov-Ketten erster, zweiter und dritter Ord- nung sowie Chi-Quadrat-Anpassungstests berechnet.