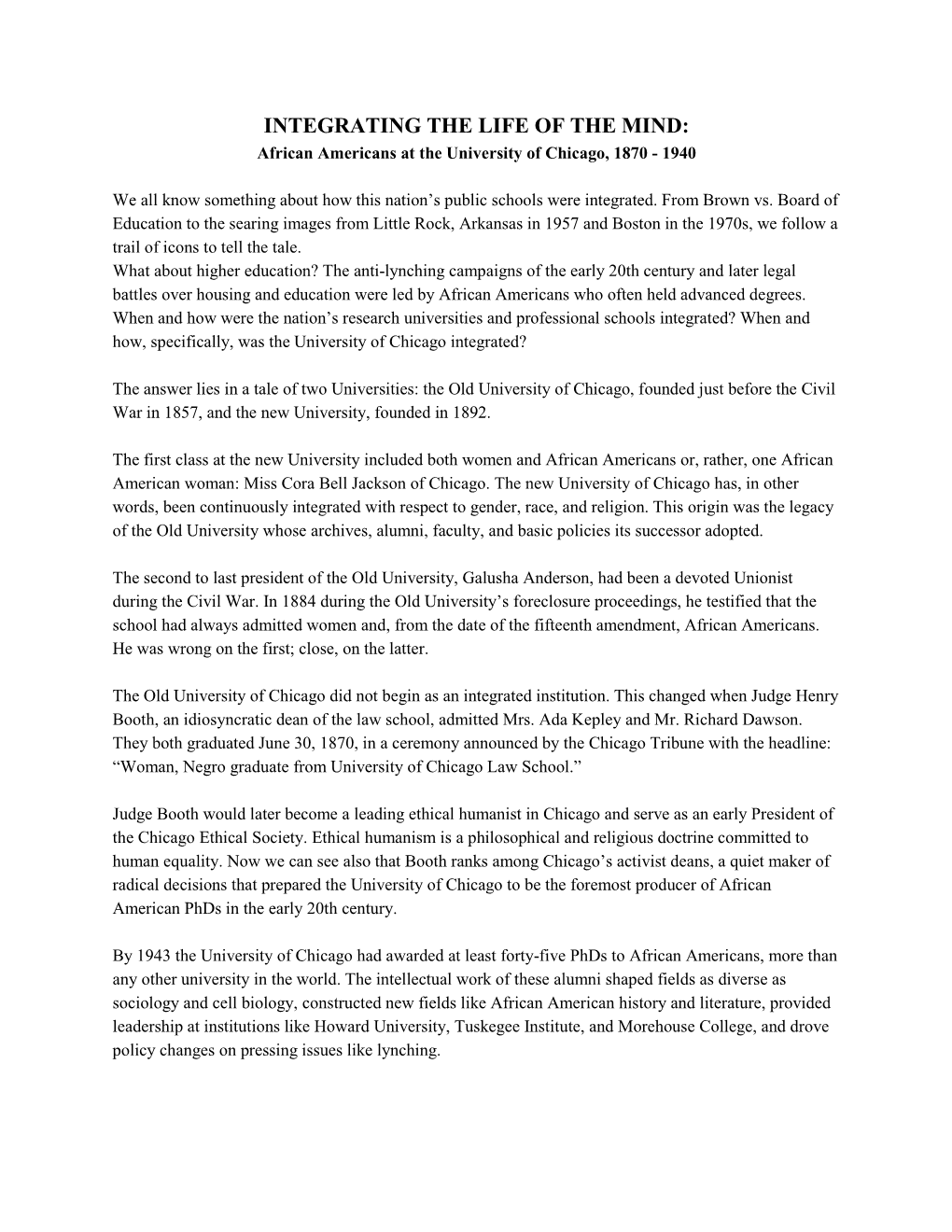

The Myth of Openness 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Roger Arliner Young (RAY) Clean Energy Fellowship

Roger Arliner Young (RAY) Errol Mazursky (he/him) Clean Energy Fellowship 2020 Cycle Informational Webinar Webinar Agenda • Story of RAY • RAY Fellows Benefits • Program Structure • RAY Host Organization Benefits • RAY Supervisor Role + Benefits • Program Fee Structure • RAY Timeline + Opportunities to be involved • Q&A Story of RAY: Green 2.0 More info: https://www.diversegreen.org/beyond-diversity/ Story of RAY: “Changing the Face” of Marine Conservation & Advocacy Story of RAY: The Person • Dr. Roger Arliner Young (1889 – November 9, 1964) o American Scientist of zoology, biology, and marine biology o First black woman to receive a doctorate degree in zoology o First black woman to conduct and publish research in her field o BS from Howard University / MS in Zoology from University of Chicago / PhD in Zoology from University of Pennsylvania o Recognized in a 2005 Congressional Resolution celebrating accomplishments of those “who have broken through many barriers to achieve greatness in science” o Learn more about Dr. Young: https://oceanconservancy.org/blog/2017/11/29/little-known-lif e-first-african-american-female-zoologist/ Story of RAY: Our Purpose • The purpose of the RAY Clean Energy Diversity Fellowship Program is to: o Build career pathways into clean energy for recent college graduates of color o Equip Fellows with tools and support to grow and serve as clean energy leaders o Promote inclusivity and culture shifts at clean energy and advocacy organizations Story of RAY: Developing the Clean Energy Fellowship Story of RAY: Our Fellow -

African American Scientists

AFRICAN AMERICAN SCIENTISTS Benjamin Banneker Born into a family of free blacks in Maryland, Banneker learned the rudiments of (1731-1806) reading, writing, and arithmetic from his grandmother and a Quaker schoolmaster. Later he taught himself advanced mathematics and astronomy. He is best known for publishing an almanac based on his astronomical calculations. Rebecca Cole Born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Cole was the second black woman to graduate (1846-1922) from medical school (1867). She joined Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell, the first white woman physician, in New York and taught hygiene and childcare to families in poor neighborhoods. Edward Alexander Born in New Haven, Connecticut, Bouchet was the first African American to Bouchet graduate (1874) from Yale College. In 1876, upon receiving his Ph.D. in physics (1852-1918) from Yale, he became the first African American to earn a doctorate. Bouchet spent his career teaching college chemistry and physics. Dr. Daniel Hale Williams was born in Pennsylvania and attended medical school in Chicago, where Williams he received his M.D. in 1883. He founded the Provident Hospital in Chicago in 1891, (1856-1931) and he performed the first successful open heart surgery in 1893. George Washington Born into slavery in Missouri, Carver later earned degrees from Iowa Agricultural Carver College. The director of agricultural research at the Tuskegee Institute from 1896 (1865?-1943) until his death, Carver developed hundreds of applications for farm products important to the economy of the South, including the peanut, sweet potato, soybean, and pecan. Charles Henry Turner A native of Cincinnati, Ohio, Turner received a B.S. -

Ledroit Park Historic Walking Tour Written by Eric Fidler, September 2016

LeDroit Park Historic Walking Tour Written by Eric Fidler, September 2016 Introduction • Howard University established in 1867 by Oliver Otis Howard o Civil War General o Commissioner of the Freedman’s Bureau (1865-74) § Reconstruction agency concerned with welfare of freed slaves § Andrew Johnson wasn’t sympathetic o President of HU (1869-74) o HU short on cash • LeDroit Park founded in 1873 by Amzi Lorenzo Barber and his brother-in-law Andrew Langdon. o Barber on the Board of Trustees of Howard Univ. o Named neighborhood for his father-in-law, LeDroict Langdon, a real estate broker o Barber went on to develop part of Columbia Heights o Barber later moved to New York, started the Locomobile car company, became the “asphalt king” of New York. Show image S • LeDroit Park built as a “romantic” suburb of Washington, with houses on spacious green lots • Architect: James McGill o Inspired by Andrew Jackson Downing’s “Architecture of Country Houses” o Idyllic theory of architecture: living in the idyllic settings would make residents more virtuous • Streets named for trees, e.g. Maple (T), Juniper (6th), Larch (5th), etc. • Built as exclusively white neighborhood in the 1870s, but from 1900 to 1910 became almost exclusively black, home of Washington’s black intelligentsia--- poets, lawyers, civil rights activists, a mayor, a Senator, doctors, professors. o stamps, the U.S. passport, two Supreme Court cases on civil rights • Fence war 1880s • Relationship to Howard Theatre 531 T Street – Originally build as a duplex, now a condo. Style: Italianate (low hipped roof, deep projecting cornice, ornate wood brackets) Show image B 525 T Street – Howard Theatre performers stayed here. -

FSE Permit Numbers by Address

ADDRESS FSE NAME FACILITY ID 00 E UNIVERSITY BLVD, FY21, UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND UMCP - XFINITY CENTER SOUTH CONCOURSE 50891 00 E UNIVERSITY BLVD, FY21, UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND UMCP - FOOTNOTES 55245 00 E UNIVERSITY BLVD, FY21, UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND UMCP - XFINITY CENTER EVENT LEVEL STANDS & PRESS P 50888 00 E UNIVERSITY BLVD, FY21, UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND UMCP - XFINITY CENTER NORTH CONCOURSE 50890 00 E UNIVERSITY BLVD, FY21, UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND UMCP - XFINITY PLAZA LEVEL 50892 1 BETHESDA METRO CTR, -, BETHESDA HYATT REGENCY BETHESDA 53242 1 BETHESDA METRO CTR, 000, BETHESDA BROWN BAG 66933 1 BETHESDA METRO CTR, 000, BETHESDA STARBUCKS COFFEE COMPANY 66506 1 BETHESDA METRO CTR, BETHESDA MORTON'S THE STEAK HOUSE 50528 1 DISCOVERY PL, SILVER SPRING DELGADOS CAFÉ 64722 1 GRAND CORNER AVE, GAITHERSBURG CORNER BAKERY #120 52127 1 MEDIMMUNE WAY, GAITHERSBURG ASTRAZENECA CAFÉ 66652 1 MEDIMMUNE WAY, GAITHERSBURG FLIK@ASTRAZENECA 66653 1 PRESIDENTIAL DR, FY21, COLLEGE PARK UMCP-UNIVERSITY HOUSE PRESIDENT'S EVENT CTR COMPLEX 57082 1 SCHOOL DR, MCPS COV, GAITHERSBURG FIELDS ROAD ELEMENTARY 54538 10 HIGH ST, BROOKEVILLE SALEM UNITED METHODIST CHURCH 54491 10 UPPER ROCK CIRCLE, ROCKVILLE MOM'S ORGANIC MARKET 65996 10 WATKINS PARK DR, LARGO KENTUCKY FRIED CHICKEN #5296 50348 100 BOARDWALK PL, GAITHERSBURG COPPER CANYON GRILL 55889 100 EDISON PARK DR, GAITHERSBURG WELL BEING CAFÉ 64892 100 LEXINGTON DR, SILVER SPRING SWEET FROG 65889 100 MONUMENT AVE, CD, OXON HILL ROYAL FARMS 66642 100 PARAMOUNT PARK DR, GAITHERSBURG HOT POT HERO 66974 100 TSCHIFFELY -

Black History, 1877-1954

THE BRITISH LIBRARY AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORY AND LIFE: 1877-1954 A SELECTIVE GUIDE TO MATERIALS IN THE BRITISH LIBRARY BY JEAN KEMBLE THE ECCLES CENTRE FOR AMERICAN STUDIES AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORY AND LIFE, 1877-1954 Contents Introduction Agriculture Art & Photography Civil Rights Crime and Punishment Demography Du Bois, W.E.B. Economics Education Entertainment – Film, Radio, Theatre Family Folklore Freemasonry Marcus Garvey General Great Depression/New Deal Great Migration Health & Medicine Historiography Ku Klux Klan Law Leadership Libraries Lynching & Violence Military NAACP National Urban League Philanthropy Politics Press Race Relations & ‘The Negro Question’ Religion Riots & Protests Sport Transport Tuskegee Institute Urban Life Booker T. Washington West Women Work & Unions World Wars States Alabama Arkansas California Colorado Connecticut District of Columbia Florida Georgia Illinois Indiana Kansas Kentucky Louisiana Maryland Massachusetts Michigan Minnesota Mississippi Missouri Nebraska Nevada New Jersey New York North Carolina Ohio Oklahoma Oregon Pennsylvania South Carolina Tennessee Texas Virginia Washington West Virginia Wisconsin Wyoming Bibliographies/Reference works Introduction Since the civil rights movement of the 1960s, African American history, once the preserve of a few dedicated individuals, has experienced an expansion unprecedented in historical research. The effect of this on-going, scholarly ‘explosion’, in which both black and white historians are actively engaged, is both manifold and wide-reaching for in illuminating myriad aspects of African American life and culture from the colonial period to the very recent past it is simultaneously, and inevitably, enriching our understanding of the entire fabric of American social, economic, cultural and political history. Perhaps not surprisingly the depth and breadth of coverage received by particular topics and time-periods has so far been uneven. -

J. HAYLEY GILLESPIE, Ph.D. Department of Biology, Texas State University, [email protected]

J. HAYLEY GILLESPIE, Ph.D. Department of Biology, Texas State University, [email protected] EDUCATION 2011 University of Texas at Austin (PhD), Ecology, Evolution & Behavior, advisor Dr. Camille Parmesan Dissertation: The ecology of the endangered Barton Springs salamander (Eurycea sosorum). 2005 University of Utah, graduate training in Stable Isotope Analysis (SIRFER lab) (Salt Lake, Utah) 2003 Austin College (BA), Biology (cum laude), minors: Fine Art & Environmental Studies (Sherman, TX) Senior Thesis Art Exhibition: Full Circle, an exhibition about environmental consciousness. TEACHING EXPERIENCE 2017-present Full Time Lecturer, Department of Biology (Modern Biology for non-majors; class size 500), Texas State University (San Marcos, TX) 2017 Visiting Professor of Biology, Huston-Tillotson University Adult Degree Program (Austin, TX) 2016-2017 Visiting Professor of Biology (general biology, and conservation biology courses), Southwestern University (Georgetown, TX) 2016 Visiting Professor of Biology (environmental biology course), Huston-Tillotson University (Austin, TX) 2014-present Informal Class Instructor (Ecology for Everyone, Natural History of Austin, Designing Effective Scientific Presentations), Art.Science.Gallery. (Austin, TX) 2013 Visiting Professor/Artist in Residence in Scientific Literacy, Skidmore College (Saratoga Springs, NY) 2013 Visiting Professor of Biology (ecology course), Southwestern University (Georgetown, TX) 2004-2010 Teaching Assistantships at the University of Texas at Austin (Austin, TX) • 4 semesters of Field Ecology Laboratory with Dr. Lawrence Gilbert at Brackenridge Field Laboratory • 3 semesters of Conservation Biology with Dr. Camille Parmesan • 6 semesters of Introductory Biology for majors with various professors 2003-2004 Middle School Science Teacher / curriculum developer, St. Alcuin Montessori School (Dallas, TX) Spring 2002 Undergraduate Ecology Teaching Assistant with Dr. -

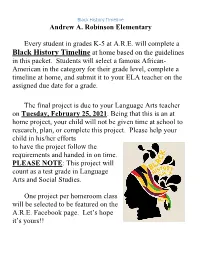

Andrew A. Robinson Elementary Every Student in Grades K-5 At

Black History Timeline Andrew A. Robinson Elementary Every student in grades K-5 at A.R.E. will complete a Black History Timeline at home based on the guidelines in this packet. Students will select a famous African- American in the category for their grade level, complete a timeline at home, and submit it to your ELA teacher on the assigned due date for a grade. The final project is due to your Language Arts teacher on Tuesday, February 25, 2021. Being that this is an at home project, your child will not be given time at school to research, plan, or complete this project. Please help your child in his/her efforts to have the project follow the requirements and handed in on time. PLEASE NOTE: This project will count as a test grade in Language Arts and Social Studies. One project per homeroom class will be selected to be featured on the A.R.E. Facebook page. Let’s hope it’s yours!! Black History Timeline Make an illustrated timeline (10 or more entries on the timeline) showing important events from the life of the person you are doing your Black History Project on. This project should be completed on a sheet of poster board. Underneath each illustration on the timeline, please create a detailed caption about what is in the illustration and the date in which the event occurred. *You must include: • A minimum of 10 entries on the timeline put in chronological order. • At least 5 entries should include an illustrated picture and detailed caption. • You must include at least one event on each of the following topics: the person’s date of birth, education, what made this figure important in African American history and their life’s accomplishment (s). -

Board of Historic Resources Quarterly Meeting 18 March 2021 Sponsor

Board of Historic Resources Quarterly Meeting 18 March 2021 Sponsor Markers – Diversity 1.) Central High School Sponsor: Goochland County Locality: Goochland County Proposed Location: 2748 Dogtown Road Sponsor Contact: Jessica Kronberg, [email protected] Original text: Central High School Constructed in 1938, Central High School served as Goochland County’s African American High School during the time of segregation. Built to replace the Fauquier Training School which burned down in 1937, the original brick structure of Central High School contained six classrooms on the 11-acre site. The school officially opened its doors to students on December 1, 1938 and housed grades eight through eleven. The 1938 structure experienced several additions over the years. In 1969, after desegregation, the building served as the County’s integrated Middle School. 86 words/ 563 characters Edited text: Central High School Central High School, Goochland County’s only high school for African American students, opened here in 1938. It replaced Fauquier Training School, which stood across the street from 1923, when construction was completed with support from the Julius Rosenwald Fund, until it burned in 1937. Central High, a six-room brick building that was later enlarged, was built on an 11-acre site with a grant from the Public Works Administration, a New Deal agency. Its academic, social, and cultural programs were central to the community. After the county desegregated its schools under federal court order in 1969, the building became a junior high school. 102 words/ 647 characters Sources: Goochland County School Board Minutes Fauquier Training/Central High School Class Reunion 2000. -

Interdisciplinary Convergences with Biology and Ethics Via Cell Biologist Ernest Everett Just and Astrobiologist Sir Fred Hoyle

Interdisciplinary Convergences with Biology and Ethics via Cell Biologist Ernest Everett Just and Astrobiologist Sir Fred Hoyle Theodore Walker Jr. Biology and ethics (general bioethics) can supplement panpsychism and panentheism. According to cell biologist Ernest Everett Just (1883-1941) ethi- cal behaviors (observable indicators of decision-making, teleology, and psy- chology) evolved from our very most primitive origins in cells. Hence, for an essential portion of the panpsychist spectrum, from cells to humans, ethical behavior is natural and necessary for evolutionary advances. Also, biology- based mind-body-cell analogy (Hartshorne 1984) can illuminate panenthe- ism. And, consistent with panpsychism, astrobiologist/cosmic biologist Sir Fred Hoyle (1915-2001) extends evolutionary biology and life-favoring teleology be- yond planet Earth (another Copernican revolution) via theories of stellar evo- lution, cometary panspermia, and cosmic evolution guided by (finely tuned by) providential cosmic intelligence, theories consistent with a panentheist natural theology that justifies ethical realism. * This deliberation is a significant reworking of »Advancing and Challenging Classical Theism with Biology and Bioethics: Astrobiology and Cosmic Biology consistent with Theology,« a 10 August 2017 paper presented at the Templeton Foundation funded international confer- ence on Analytic Theology and the Nature of God: Advancing and Challenging Classical Theism (7-12 August 2017) at Hochschule für Philosophie München [Munich School of Philosophy] at Fürstenried Palace, Exerzitienhaus Schloss Fürstenried, in Munich, DE— Germany. Conference speakers included: John Bishop, University of Auckland, New Zealand; Joseph Bracken SJ, Xavier University Cincinnati; Godehard Brüntrup SJ, Munich School of Philosophy; Anna Case-Winters, McCormick Theological Seminary; Philip Clayton, Claremont School of Theology; Benedikt Göcke, Ruhr University Bochum; Johnathan D. -

Influential Black Biologists

INFLUENTIAL BLACK BIOLOGISTS Lesson Plan Adaptable for all ages and abilities A NOTE TO EDUCATORS AND PARENTS Please take care to review any content before sharing with your students, especially from the external links provided, to make sure it is age appropriate. OBJECTIVES • To learn about influential Black biologists who advanced their field and added to scientific knowledge • To understand the importance of diversity in science • To provide inspiration for future biologists • To provide links to careers advice and guidance WARM-UP As a warm-up exercise, get your pupils to think about as many scientists as they can in one minute. Either have them write this down or do it as a group discussion. How many Scientists on their lists are Black? Discuss with your pupils whether the scientists they came up with represents the make-up of society. Why do they think this is the case? Depending on the age and level of your students, you may wish to draw on points raised in some of the following articles for this discussion: • What is racism - and what can be done about it? (CBBC Newsround) White men still dominate in UK academic science (Nature) • White men’s voices still dominate public science. Here’s how to change this (The Conversation) • The Ideology of Racism: Misusing Science to Justify Racial Discrimination (United Nations) Use the wordsearch (on page 5) provided to start a discussion around which of these Biologists your pupils have or have not heard about. What topics did these scientists research? Which scientific topics sound the most and least interesting to each of the pupil and why? 1/4 RESEARCH Using the “suggested list of people to research further” (on page 4) and the “wordsearch” (on page 5) as a starting point, get your students to select an interesting biologist who inspires them, or who has made a notable discovery. -

Celebrates 25 Years. 25Th Anniversary Collector’S Edition Dear Students, Educators,And Friends

South Carolina African American History Calendar Celebrates 25 Years. 25th Anniversary Collector’s Edition Dear Students, Educators,and Friends, One of the highlights of my year is the unveiling of the new African American History Calendar, for it is always a wonderful time of renewing friendships, connecting with new acquaintances, and honoring a remarkable group of South Carolinians. This year is even more exciting, for the 2014 calendar is our 25th Anniversary Edition! For a quarter of a century, the Calendar project has celebrated the lives, leadership, and experiences of gifted people who have shaped who we are as a State and as South Carolinians. Initially developed as a resource for teachers as they include African American history in their classroom curriculum, the Calendar has become a virtual Hall of Fame, combining recognition with education and drawing online visitors from around the globe. Thus far, 297 African Americans with South Carolina roots have been featured on the Calendar’s pages. They represent a wide array of endeavors, including government and military service, education, performing and fine arts, business, community activism, and athletics. They hail from every corner of the state, from rural communities to our largest cities. And each has made a difference for people and for their communities. The Calendar, with its supporting educational materials, has always been designed to help students understand that history is about people and their actions, not simply dates or places. While previous editions have focused on individuals, the 25th Anniversary Edition spotlights 12 milestone events in South Carolina’s African American History. Driven by men and women of courage and conviction, these events helped lay the foundation for who we are today as a State and who we can become. -

![Environmental History] Orosz, Joel](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6654/environmental-history-orosz-joel-2026654.webp)

Environmental History] Orosz, Joel

Amrys O. Williams Science in America Preliminary Exam Reading List, 2008 Supervised by Gregg Mitman Classics, Overviews, and Syntheses Robert Bruce, The Launching of Modern American Science, 1846-1876 (New York: Knopf, 1987). George H. Daniels, American Science in the Age of Jackson (New York: Columbia University Press, 1968). ————, Science in American Society (New York: Knopf, 1971). Sally Gregory Kohlstedt and Margaret Rossiter (eds.), Historical Writing on American Science (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1985). Ronald L. Numbers and Charles Rosenberg (eds.), The Scientific Enterprise in America: Readings from Isis (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996). Nathan Reingold, Science, American Style. (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1991). Charles Rosenberg, No Other Gods: On Science and American Social Thought (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1976). Science in the Colonies Joyce Chaplin, Subject Matter: Technology, the Body, and Science on the Anglo- American Frontier, 1500-1676 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001). [crosslisted with History of Technology] John C. Greene, American Science in the Age of Jefferson (Ames: Iowa State University Press, 1984). Katalin Harkányi, The Natural Sciences and American Scientists in the Revolutionary Era (New York: Greenwood Press, 1990). Brooke Hindle, The Pursuit of Science in Revolutionary America, 1735-1789. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1956). Judith A. McGaw, Early American Technology: Making and Doing Things from the Colonial Era to 1850 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press for the Institute of Early American History and Culture, 1994). [crosslisted with History of Technology] Elizabeth Wagner Reed, American Women in Science Before the Civil War (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1992).