Nineteenth Century Healthcare Was Not the Industry It Is Today. Before The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ledroit Park Historic Walking Tour Written by Eric Fidler, September 2016

LeDroit Park Historic Walking Tour Written by Eric Fidler, September 2016 Introduction • Howard University established in 1867 by Oliver Otis Howard o Civil War General o Commissioner of the Freedman’s Bureau (1865-74) § Reconstruction agency concerned with welfare of freed slaves § Andrew Johnson wasn’t sympathetic o President of HU (1869-74) o HU short on cash • LeDroit Park founded in 1873 by Amzi Lorenzo Barber and his brother-in-law Andrew Langdon. o Barber on the Board of Trustees of Howard Univ. o Named neighborhood for his father-in-law, LeDroict Langdon, a real estate broker o Barber went on to develop part of Columbia Heights o Barber later moved to New York, started the Locomobile car company, became the “asphalt king” of New York. Show image S • LeDroit Park built as a “romantic” suburb of Washington, with houses on spacious green lots • Architect: James McGill o Inspired by Andrew Jackson Downing’s “Architecture of Country Houses” o Idyllic theory of architecture: living in the idyllic settings would make residents more virtuous • Streets named for trees, e.g. Maple (T), Juniper (6th), Larch (5th), etc. • Built as exclusively white neighborhood in the 1870s, but from 1900 to 1910 became almost exclusively black, home of Washington’s black intelligentsia--- poets, lawyers, civil rights activists, a mayor, a Senator, doctors, professors. o stamps, the U.S. passport, two Supreme Court cases on civil rights • Fence war 1880s • Relationship to Howard Theatre 531 T Street – Originally build as a duplex, now a condo. Style: Italianate (low hipped roof, deep projecting cornice, ornate wood brackets) Show image B 525 T Street – Howard Theatre performers stayed here. -

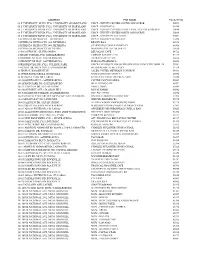

FSE Permit Numbers by Address

ADDRESS FSE NAME FACILITY ID 00 E UNIVERSITY BLVD, FY21, UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND UMCP - XFINITY CENTER SOUTH CONCOURSE 50891 00 E UNIVERSITY BLVD, FY21, UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND UMCP - FOOTNOTES 55245 00 E UNIVERSITY BLVD, FY21, UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND UMCP - XFINITY CENTER EVENT LEVEL STANDS & PRESS P 50888 00 E UNIVERSITY BLVD, FY21, UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND UMCP - XFINITY CENTER NORTH CONCOURSE 50890 00 E UNIVERSITY BLVD, FY21, UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND UMCP - XFINITY PLAZA LEVEL 50892 1 BETHESDA METRO CTR, -, BETHESDA HYATT REGENCY BETHESDA 53242 1 BETHESDA METRO CTR, 000, BETHESDA BROWN BAG 66933 1 BETHESDA METRO CTR, 000, BETHESDA STARBUCKS COFFEE COMPANY 66506 1 BETHESDA METRO CTR, BETHESDA MORTON'S THE STEAK HOUSE 50528 1 DISCOVERY PL, SILVER SPRING DELGADOS CAFÉ 64722 1 GRAND CORNER AVE, GAITHERSBURG CORNER BAKERY #120 52127 1 MEDIMMUNE WAY, GAITHERSBURG ASTRAZENECA CAFÉ 66652 1 MEDIMMUNE WAY, GAITHERSBURG FLIK@ASTRAZENECA 66653 1 PRESIDENTIAL DR, FY21, COLLEGE PARK UMCP-UNIVERSITY HOUSE PRESIDENT'S EVENT CTR COMPLEX 57082 1 SCHOOL DR, MCPS COV, GAITHERSBURG FIELDS ROAD ELEMENTARY 54538 10 HIGH ST, BROOKEVILLE SALEM UNITED METHODIST CHURCH 54491 10 UPPER ROCK CIRCLE, ROCKVILLE MOM'S ORGANIC MARKET 65996 10 WATKINS PARK DR, LARGO KENTUCKY FRIED CHICKEN #5296 50348 100 BOARDWALK PL, GAITHERSBURG COPPER CANYON GRILL 55889 100 EDISON PARK DR, GAITHERSBURG WELL BEING CAFÉ 64892 100 LEXINGTON DR, SILVER SPRING SWEET FROG 65889 100 MONUMENT AVE, CD, OXON HILL ROYAL FARMS 66642 100 PARAMOUNT PARK DR, GAITHERSBURG HOT POT HERO 66974 100 TSCHIFFELY -

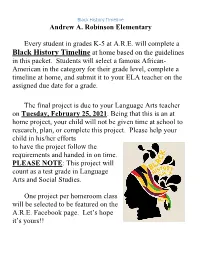

Andrew A. Robinson Elementary Every Student in Grades K-5 At

Black History Timeline Andrew A. Robinson Elementary Every student in grades K-5 at A.R.E. will complete a Black History Timeline at home based on the guidelines in this packet. Students will select a famous African- American in the category for their grade level, complete a timeline at home, and submit it to your ELA teacher on the assigned due date for a grade. The final project is due to your Language Arts teacher on Tuesday, February 25, 2021. Being that this is an at home project, your child will not be given time at school to research, plan, or complete this project. Please help your child in his/her efforts to have the project follow the requirements and handed in on time. PLEASE NOTE: This project will count as a test grade in Language Arts and Social Studies. One project per homeroom class will be selected to be featured on the A.R.E. Facebook page. Let’s hope it’s yours!! Black History Timeline Make an illustrated timeline (10 or more entries on the timeline) showing important events from the life of the person you are doing your Black History Project on. This project should be completed on a sheet of poster board. Underneath each illustration on the timeline, please create a detailed caption about what is in the illustration and the date in which the event occurred. *You must include: • A minimum of 10 entries on the timeline put in chronological order. • At least 5 entries should include an illustrated picture and detailed caption. • You must include at least one event on each of the following topics: the person’s date of birth, education, what made this figure important in African American history and their life’s accomplishment (s). -

Interdisciplinary Convergences with Biology and Ethics Via Cell Biologist Ernest Everett Just and Astrobiologist Sir Fred Hoyle

Interdisciplinary Convergences with Biology and Ethics via Cell Biologist Ernest Everett Just and Astrobiologist Sir Fred Hoyle Theodore Walker Jr. Biology and ethics (general bioethics) can supplement panpsychism and panentheism. According to cell biologist Ernest Everett Just (1883-1941) ethi- cal behaviors (observable indicators of decision-making, teleology, and psy- chology) evolved from our very most primitive origins in cells. Hence, for an essential portion of the panpsychist spectrum, from cells to humans, ethical behavior is natural and necessary for evolutionary advances. Also, biology- based mind-body-cell analogy (Hartshorne 1984) can illuminate panenthe- ism. And, consistent with panpsychism, astrobiologist/cosmic biologist Sir Fred Hoyle (1915-2001) extends evolutionary biology and life-favoring teleology be- yond planet Earth (another Copernican revolution) via theories of stellar evo- lution, cometary panspermia, and cosmic evolution guided by (finely tuned by) providential cosmic intelligence, theories consistent with a panentheist natural theology that justifies ethical realism. * This deliberation is a significant reworking of »Advancing and Challenging Classical Theism with Biology and Bioethics: Astrobiology and Cosmic Biology consistent with Theology,« a 10 August 2017 paper presented at the Templeton Foundation funded international confer- ence on Analytic Theology and the Nature of God: Advancing and Challenging Classical Theism (7-12 August 2017) at Hochschule für Philosophie München [Munich School of Philosophy] at Fürstenried Palace, Exerzitienhaus Schloss Fürstenried, in Munich, DE— Germany. Conference speakers included: John Bishop, University of Auckland, New Zealand; Joseph Bracken SJ, Xavier University Cincinnati; Godehard Brüntrup SJ, Munich School of Philosophy; Anna Case-Winters, McCormick Theological Seminary; Philip Clayton, Claremont School of Theology; Benedikt Göcke, Ruhr University Bochum; Johnathan D. -

Celebrates 25 Years. 25Th Anniversary Collector’S Edition Dear Students, Educators,And Friends

South Carolina African American History Calendar Celebrates 25 Years. 25th Anniversary Collector’s Edition Dear Students, Educators,and Friends, One of the highlights of my year is the unveiling of the new African American History Calendar, for it is always a wonderful time of renewing friendships, connecting with new acquaintances, and honoring a remarkable group of South Carolinians. This year is even more exciting, for the 2014 calendar is our 25th Anniversary Edition! For a quarter of a century, the Calendar project has celebrated the lives, leadership, and experiences of gifted people who have shaped who we are as a State and as South Carolinians. Initially developed as a resource for teachers as they include African American history in their classroom curriculum, the Calendar has become a virtual Hall of Fame, combining recognition with education and drawing online visitors from around the globe. Thus far, 297 African Americans with South Carolina roots have been featured on the Calendar’s pages. They represent a wide array of endeavors, including government and military service, education, performing and fine arts, business, community activism, and athletics. They hail from every corner of the state, from rural communities to our largest cities. And each has made a difference for people and for their communities. The Calendar, with its supporting educational materials, has always been designed to help students understand that history is about people and their actions, not simply dates or places. While previous editions have focused on individuals, the 25th Anniversary Edition spotlights 12 milestone events in South Carolina’s African American History. Driven by men and women of courage and conviction, these events helped lay the foundation for who we are today as a State and who we can become. -

![Environmental History] Orosz, Joel](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6654/environmental-history-orosz-joel-2026654.webp)

Environmental History] Orosz, Joel

Amrys O. Williams Science in America Preliminary Exam Reading List, 2008 Supervised by Gregg Mitman Classics, Overviews, and Syntheses Robert Bruce, The Launching of Modern American Science, 1846-1876 (New York: Knopf, 1987). George H. Daniels, American Science in the Age of Jackson (New York: Columbia University Press, 1968). ————, Science in American Society (New York: Knopf, 1971). Sally Gregory Kohlstedt and Margaret Rossiter (eds.), Historical Writing on American Science (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1985). Ronald L. Numbers and Charles Rosenberg (eds.), The Scientific Enterprise in America: Readings from Isis (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996). Nathan Reingold, Science, American Style. (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1991). Charles Rosenberg, No Other Gods: On Science and American Social Thought (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1976). Science in the Colonies Joyce Chaplin, Subject Matter: Technology, the Body, and Science on the Anglo- American Frontier, 1500-1676 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001). [crosslisted with History of Technology] John C. Greene, American Science in the Age of Jefferson (Ames: Iowa State University Press, 1984). Katalin Harkányi, The Natural Sciences and American Scientists in the Revolutionary Era (New York: Greenwood Press, 1990). Brooke Hindle, The Pursuit of Science in Revolutionary America, 1735-1789. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1956). Judith A. McGaw, Early American Technology: Making and Doing Things from the Colonial Era to 1850 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press for the Institute of Early American History and Culture, 1994). [crosslisted with History of Technology] Elizabeth Wagner Reed, American Women in Science Before the Civil War (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1992). -

Integrating the Life of the Mind, Danielle Allen

Integrating the Life of the Mind Item Captions, Danielle Allen Case 1: The Myth of Openness 1. In the U.S. Circuit Court, N. District of Illinois, The Union Mutual Life Insurance Co. vs. The University of Chicago. p. 172 Old University of Chicago Records. This document records the testimony of University of Chicago President Galusha Anderson in the 1884 foreclosure proceedings against the old University. 2. Photograph of Galusha Anderson, [n.d.]. Archival Photographic Files. Anderson was born in 1832 and trained at Rochester Theological Seminary. He served as pastor of Second Baptist Church in St. Louis from 1858-1866 and of Second Baptist in Chicago from 1876 to 1878 when he became fifth president of the University of Chicago. He left the old University when it closed in 1886 but in 1892 returned to the new University as professor in the Divinity School, from which he retired in 1904. He died in 1918. 3. Galusha Anderson. The Story of a Border City during the Civil War. Boston: Little, Brown, and Co., 1908. Rare Book Collection, Gift of Danielle Allen. In retirement, Anderson wrote this memoir of his time as pastor of Second Baptist in St. Louis during the Civil War. He had worked aggressively to keep Missouri in the Union and devoted considerable energy to the establishment of “negro schools” throughout the city. 4. Testimony Taken by the Joint Select Committee to Inquire into the Condition of Affairs in the Late Insurrectionary States, South Carolina. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1872. Vol. 3. General Collections. The Old University of Chicago was struggling to find its feet in the same years that the country was struggling with the consequences of the Civil War. -

8 02 Black History Month 2013 Bd Mtg 2014 01 16

BLACK HISTORY MONTH 2014 African Americans in the Sciences BLACK HISTORY IS AMERICAN HISTORY HIGHLIGHTED OF BLACK ACHIEVEMENTS The creative contributions in all fields throughout the world. With this background, both Black students and students from other cultures and races can gain a new-found appreciation for this heritage as well as a better understanding of the framework in which ongoing struggles are still taking place. All students need to feel affirmed; need to be aware of the contributions made by Blacks in America RATIONALE Focus Areas The history of black Impact the educational achievement outcomes for all students, The history and creative teachers and families in East output of black peoples in the Side Union High School literary, visual, musical, District history, athletics, social studies, sciences and performing arts Improve educational progress and status of African American male and female students ,their nations, and the world. WHY BLACK HISTORY MONTH Black history is still a largely neglected part of American history. "I hear a lot of African American young people say things like, 'How come they gave us the shortest month of the year?' “Nobody gave anybody anything.” Carter G. Woodson chose February because it includes the birthdays of abolitionist Frederick Douglass and President Abraham Lincoln. SELF-ADVOCACY Carter Godwin Woodson - Born in West Virginia in 1875 His parents were former slaves and instilled in him the value of education . He went on to earn a degree in literature from Berea College. He was the second African American to earn a doctorate from Harvard University, Woodson's being in history. -

3414 Hon. Bobby L. Rush Hon. John Lewis Hon. Ron Paul

3414 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS March 2, 1999 H. CON. RES. 38, PAUL ROBESON gery? And that Ernest Everett Just, Percy Ju- taxes. Simply by raising teacher’s take-home COMMEMORATIVE POSTAGE lian and George Washington Carver were all pay via a $1,000 tax credit we can accomplish STAMP outstanding scientists? Educators such as a number of important things. First, we show W.E.B. DuBois and Benjamin E. Mays left an a true commitment to education. We also let HON. BOBBY L. RUSH indelible mark on this country. The Harlem America’s teachers know that the American OF ILLINOIS Renaissance produced poets, writers and mu- people and the Congress respect their work. IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES sicians like Countee Cullen, Langston Hughes Finally, and perhaps most importantly, by rais- and Duke Ellington. The civil rights movement ing teacher take-home pay, the Teacher Tax Tuesday, March 2, 1999 changed the face of this country and inspired Cut Act encourages high-quality professionals Mr. RUSH. Mr. Speaker, I am pleased today movements toward democracy and justice all to enter, and remain in, the teaching profes- to join with several of my colleagues in intro- over the world—producing great leaders like sion. ducing a Concurrent Resolution urging the Martin Luther King, Jr., and Whitney Young. In conclusion, Mr. Speaker, I once again U.S. Postal Service’s Citizen Stamp Advisory Too few people know that Benjamin Banneker, ask my colleagues to put aside partisan bick- Committee to issue a commemorative postage an outstanding mathematician, along with ering and unite around the idea of helping stamp honoring Paul Leroy Robeson. -

African American Heritage Trail Washington, DC Dear Washingtonians and Visitors

African American Heritage Trail Washington, DC Dear Washingtonians and Visitors, Welcome to the African American Heritage Trail for Washington, DC! It is my honor to present this latest edition of the guide to the inspiring history of African Americans in this world-class city. From Benjamin Banneker’s essential role in the survey of the District in 1791, to the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech at the Lincoln Memorial in 1963 and beyond, African Americans have made DC a capital of activism and culture. John H. Fleet, a physician, teacher, and abolitionist, called Georgetown home. Ralph J. Bunche, a professor, United Nations negotiator, and Nobel Peace Prize recipi- ent settled in Brookland. Anthony Bowen, an abolitionist, community leader, and Underground Railroad conductor changed the world from a modest home in Southwest. Washington is where advisor to U.S. presidents Mary McLeod Bethune, activist A. Phillip Randolph, poet Paul Laurence Dunbar, and visual artist Lois Mailou Jones all lived and made their careers. On the African American Heritage Trail, you’ll see important sites in the lives of each of these remarkable people. You’ll also encounter U Street, long a hub for African American theater and music; Howard University, the flagship of African American higher education; and Anacostia, a historic black suburb once home to Frederick Douglass. Alongside these paragons of American history and culture, generations of African Americans from all walks of life built strong communities, churches, businesses, Front cover: Esquisse for Ode to Kinshasa by Lois Mailou Jones, and other institutions that have made DC the vital city Museum of Women in the Arts; George E.C. -

Fse Name Address Facility Id & Pizza 258 Crown Park

FSE NAME ADDRESS FACILITY ID & PIZZA 258 CROWN PARK AVE, GAITHERSBURG 64663 & PIZZA 7614 OLD GEORGETOWN RD, 000, BETHESDA 57806 & PIZZA 19823 CENTURY BLVD, GERMANTOWN 57982 & PIZZA 3500 EAST WEST HWY, HYATTSVILLE 66692 & PIZZA 11626 OLD GEORGETOWN RD, ROCKVILLE 57899 100 PLUS LATINO RESTAURANT 5824 ALLENTOWN WAY, TEMPLE HILLS 55408 1000 DEGREES PIZZA- WOODMORE 9201 WOODMORE CENTRE DR, GLENARDEN 66100 168 ASIAN BURRITO 18000 GEORGIA AVE., OLNEY 66900 2 BEANS IN A CUP 6125 MONTROSE RD, ROCKVILLE 67355 29 CONVENIENCE MART 10755 COLESVILLE RD, SILVER SPRING 58006 301 TRAVEL PLAZA/CIRCLE K CONVENIENCE 3511 CRAIN HWY, CD, UPPER MARLBORO 65106 5 BREADS & 2 FISH 3500 EAST WEST HWY, HYATTSVILLE 57767 5 SISTERS RESTAURANT LOUNGE 12617 LAUREL BOWIE RD, -, LAUREL 64444 7 - ELEVEN STORE 6570 COVENTRY WAY, CLINTON 50913 7 - ELEVEN STORE 13880 O COLUMBIA PK, SILVER SPRING 52446 7 - ELEVEN STORE #23691 15585 O COLUMBIA PK, CD, BURTONSVILLE 52870 7 BILLIARDS 15966 SHADY GROVE RD, FY21 CLO2, GAITHERSBURG 65770 7 ELEVEN # 1038936 20510 FREDERICK RD, GERMANTOWN 66104 7- ELEVEN STORE 36494H 8484 GEORGIA AVE, SILVER SPRING 50854 7-11 5415KENILWORTH AVE, RIVERDALE 51542 7-11 2000 EAST UNIVERSITY BLVD, HYATTSVILLE 57614 7-11 14430 LAYHILL RD, SILVER SPRING 52873 7-11 14001 BALTIMORE AVE, LAUREL 50006 7-11 8461ANNAPOLIS RD, CD, NEW CARROLLTON 50164 7-11 3411 DALLAS DR, TEMPLE HILLS 51281 7-11 8101 FENTON ST, SILVER SPRING 50215 7-11 6116 MARLBORO PIKE, DISTRICT HEIGHTS 65378 7-11 # 11664 4404 KNOX Rd, COLLEGE PARK 50342 7-11 # 11666 900 MERRIMAC DR, TAKOMA PARK -

The Faces of Science: African Americans in the Sciences

The Faces of Science: African Americans in the Sciences Profiled here are African American men and women who have contributed to the advancement of science and engineering. The accomplishments of the past and present can serve as pathfinders to present and future engineers and scientists. African American chemists, biologists, inventors, engineers, and mathematicians have contributed in both large and small ways that can be overlooked when chronicling the history of science. By describing the scientific history of selected African American men and women we can see how the efforts of individuals have advanced human understanding in the world around us. https://webfiles.uci.edu/mcbrown/display/faces.html Biochemists Biologists Chemists Physicists Herman Branson William Michael Bright Albert C. Antoine George E. Alcorn George Washington Carver Hyman Yates Chase Thomas Nelson Baker, Jr. Edward Bouchet Emmett W. Chappelle Jewel Plummer Cobb St. Elmo Brady Robert Henry Bragg Marie M. Daly Alfred O. Coffin E. Luther Brookes Herman R. Branson Lloyd Hall Dale Emeagwali Edward M.A. Chandler George R. Carruthers Ernest E. Just Mary Styles Harris George Washington Carver Ernest Coleman Samuel Lee Kountz, Jr. Jehu Callis Hunter John R. Cooper John William Coleman James Sumner Lee Ernest Everett Just Lloyd Hall Stanley Peter Davis Dorothy McClendon James Sumner Lee James Harris Meredith C. Gourdine Ruth Ella Moore Roger Arliner Young Henry Aaron Hill John McNeile Hunter Kenneth Olden Kenneth Olden John Edward Hodge Elmer Samuel Imes Ida Owens John McNeile Hunter Shirley Ann Jackson Maurice Rabb Elmer Samuel Imes Katherine G. Johnson Lovell A. Jones Roscoe L. Koontz Percy Lavon Julian Walter Eugene Massey Ernest Just Louis W.