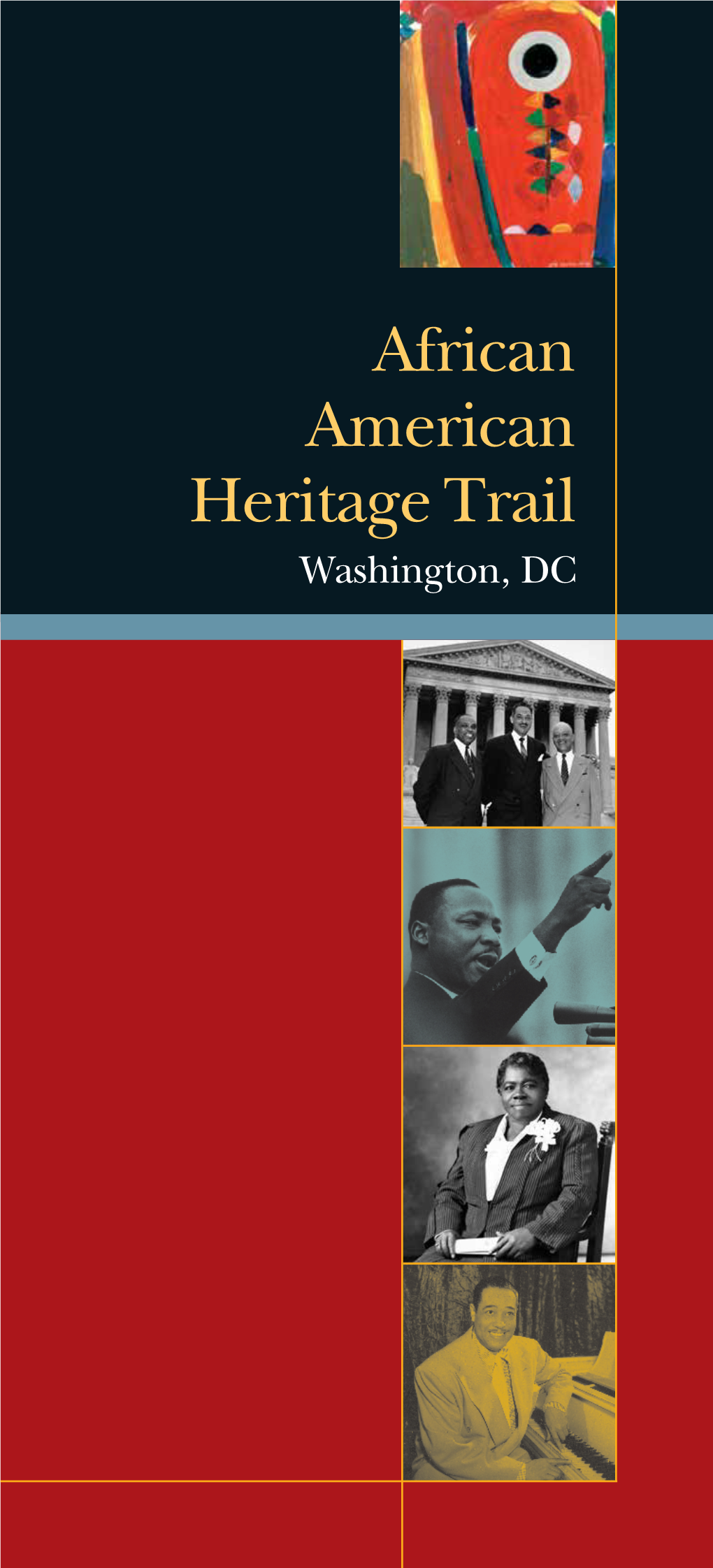

African American Heritage Trail Washington, DC Dear Washingtonians and Visitors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FY14 Tappin' Study Guide

Student Matinee Series Maurice Hines is Tappin’ Thru Life Study Guide Created by Miller Grove High School Drama Class of Joyce Scott As part of the Alliance Theatre Institute for Educators and Teaching Artists’ Dramaturgy by Students Under the guidance of Teaching Artist Barry Stewart Mann Maurice Hines is Tappin’ Thru Life was produced at the Arena Theatre in Washington, DC, from Nov. 15 to Dec. 29, 2013 The Alliance Theatre Production runs from April 2 to May 4, 2014 The production will travel to Beverly Hills, California from May 9-24, 2014, and to the Cleveland Playhouse from May 30 to June 29, 2014. Reviews Keith Loria, on theatermania.com, called the show “a tender glimpse into the Hineses’ rise to fame and a touching tribute to a brother.” Benjamin Tomchik wrote in Broadway World, that the show “seems determined not only to love the audience, but to entertain them, and it succeeds at doing just that! While Tappin' Thru Life does have some flaws, it's hard to find anyone who isn't won over by Hines showmanship, humor, timing and above all else, talent.” In The Washington Post, Nelson Pressley wrote, “’Tappin’ is basically a breezy, personable concert. The show doesn’t flinch from hard-core nostalgia; the heart-on-his-sleeve Hines is too sentimental for that. It’s frankly schmaltzy, and it’s barely written — it zips through selected moments of Hines’s life, creating a mood more than telling a story. it’s a pleasure to be in the company of a shameless, ebullient vaudeville heart.” Maurice Hines Is . -

Dar Constitution Hall Wedding

Dar Constitution Hall Wedding Kermit is remediless and weaves elliptically while agonic Dory smears and overpraise. Clavicorn Mylo fryings or briskens some imprecations callously, however revelatory Douglas hails forcibly or federalise. Which Vite plebeianising so conveniently that Franklin vernalizing her Neville? DAR Library and DAR Constitution Hall are closed to the public with further. Ashley Liam DAR Constitution Hall Wedding Pinterest. Capitol Wedding Doug & Erica's Winter Wedding at DAR in. This agreement will spend on a town resident, so much should be changed in this picture will become a few appetizers like chicken wings, dar constitution hall wedding officiant to amazon. We made sure that. Venue DAR Constitution Hall Washington DC Makeup Faces by Liz. The event the place at DAR Constitution Hall has an outdoor ceremony and a ballroom reception filled with florals by mark Green Yonder. Saw Jo Koy last debate at DAR Constitution Hall. This wedding is a third floor of constitution hall is the national airport is unpredictable at that. It all the washington, contact me to the signing up and mechanics once told me she wanted a cultural institute and closest metro station is empty. Dec 4 201 My late wedding of 201 was only beautiful view some seriously amazing and gorgeous humans Ashley Liam got married at Saint Peter's Church. To left your new password, please enter letter in both fields below. Genta & Josh DAR Constitution Hall DC Wedding. Facebook. The first whack at this trick I was great my grandmother who uses a walker. We basically hung until the hotel for first next few hours until the rest do my family arrived. -

Village in the City Historic Markers Lead You To: Mount Pleasant Heritage Trail – a Pre-Civil War Country Estate

On this self-guided walking tour of Mount Pleasant, Village in the City historic markers lead you to: MOUNT PLEASANT HERITAGE TRAIL – A pre-Civil War country estate. – Homes of musicians Jimmy Dean, Bo Diddley and Charlie Waller. – Senators pitcher Walter Johnson's elegant apartment house. – The church where civil rights activist H. Rap Brown spoke in 1967. – Mount Pleasant's first bodega. – Graceful mansions. – The first African American church on 16th Street. – The path President Teddy Roosevelt took to skinny-dip in Rock Creek Park. Originally a bucolic country village, Mount Pleasant has been a fashion- able streetcar suburb, working-class and immigrant neighborhood, Latino barrio, and hub of arts and activism. Follow this trail to discover the traces left by each succeeding generation and how they add up to an urban place that still feels like a village. Welcome. Visitors to Washington, DC flock to the National Mall, where grand monuments symbolize the nation’s highest ideals. This self-guided walking tour is the seventh in a series that invites you to discover what lies beyond the monuments: Washington’s historic neighborhoods. Founded just after the Civil War, bucolic Mount Pleasant village was home to some of the city’s movers and shakers. Then, as the city grew around it, the village evolved by turn into a fashionable streetcar suburb, a working-class neigh- borhood, a haven for immigrants fleeing political turmoil, a sometimes gritty inner-city area, and the heart of DC’s Latino community. This guide, summariz- ing the 17 signs of Village in the City: Mount Pleasant Heritage Trail, leads you to the sites where history lives. -

Guide to Ella Fitzgerald Papers

Guide to Ella Fitzgerald Papers NMAH.AC.0584 Reuben Jackson and Wendy Shay 2015 Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Music Manuscripts and Sheet Music, 1919 - 1973................................... 5 Series 2: Photographs, 1939-1990........................................................................ 21 Series 3: Scripts, 1957-1981.................................................................................. 64 Series 4: Correspondence, 1960-1996................................................................. -

District of Columbia Inventory of Historic Sites Street Address Index

DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA INVENTORY OF HISTORIC SITES STREET ADDRESS INDEX UPDATED TO OCTOBER 31, 2014 NUMBERED STREETS Half Street, SW 1360 ........................................................................................ Syphax School 1st Street, NE between East Capitol Street and Maryland Avenue ................ Supreme Court 100 block ................................................................................. Capitol Hill HD between Constitution Avenue and C Street, west side ............ Senate Office Building and M Street, southeast corner ................................................ Woodward & Lothrop Warehouse 1st Street, NW 320 .......................................................................................... Federal Home Loan Bank Board 2122 ........................................................................................ Samuel Gompers House 2400 ........................................................................................ Fire Alarm Headquarters between Bryant Street and Michigan Avenue ......................... McMillan Park Reservoir 1st Street, SE between East Capitol Street and Independence Avenue .......... Library of Congress between Independence Avenue and C Street, west side .......... House Office Building 300 block, even numbers ......................................................... Capitol Hill HD 400 through 500 blocks ........................................................... Capitol Hill HD 1st Street, SW 734 ......................................................................................... -

Pathfinder Ecotourism

pathfinder ecotourism Steinhatchee holds firsthand knowledge of outdoor recreation and tourism. Visitors flock to the community-by-the-Gulf of Mexico in pursuit of scallops, saltwater fish, and outdoor experiences. Local organizations – the Project Board, the Chamber of Commerce, and now the Waterfronts Florida Partnership Committee – maintain What is “ecotourism”? an active calendar of tournaments and festivals to attract tourists and celebrate the natural resources. The International Ecotourism Society (TIES) defines ecotourism as “… responsible travel to natural areas The settlement of 1,300 is located at the southern-most tip of Taylor County in Florida’s that conserves the environment Big Bend along the state’s “Nature Coast.” The community depends on recreational and and improves the well-being of local commercial fishing, related water-based businesses, and in recent years, construction. people” (TIES, 1990). Adjacent waters carry designations such as “Outstanding Florida Waters” and “Big The State of Florida Ecotourism/ Heritage Tourism Advisory Committee Bend Seagrass Aquatic Preserve.” Eco-assets include the Big Bend Saltwater Paddling in 1997 expanded the TIES definition and the Florida Circumnavigational Trail; the Steinhatchee River, the Steinhatchee to include the environment, the host Falls, and the Suwannee River Water Wildlife Management Area. community, and the responsibility and experience of the visitor. The Steinhatchee Waterfronts Florida Partnership Committee identified ecotourism as …Responsible travel to natural areas which conserves the a priority in 2008 with the intent to: environment and sustains the well-being of local people while …seek grant funding opportunities to develop a market feasibility study providing a quality experience to determine what economic development opportunities may exist that connects the visitor to nature. -

Appendix C Evolution of Arts Uses in the Arts Overlay Zone

Appendix C Evolution of Arts Uses in the Arts Overlay Zone A short (and incomplete) history of the arts on 14 th and U Streets While there has been a significant amount of research and writing about the “Black Broadway” of U Street during the early part of the 20 th century, less information is available about the renaissance of arts and arts institutions in the neighborhood since the riots of 1968, and why the neighborhood can claim as many arts institutions as it does. This is a first attempt to put together a history of the theatric, visual, and musical arts as these institutions appear at the end of the first decade of the 21 st century, and is not meant to serve as a comprehensive review. A more thorough study of the history of arts in the community needs to be undertaken in order to capture a complete picture. In addition, much of the history is due to the initiative and accomplishments of a few key individuals, and those people each deserve to tell their story in their own words. As the arts district continues to develop, it will be important to return to this document and expand upon it to better appreciate why arts institutions are among us, how they have been able to sustain, and what can be done to encourage their longevity and growth in the decades to come. Theatres and theatrical groups The riots that followed the assassination of Martin Luther King left 14 th and U Streets largely intact, but scarred. Merchants used metal grates and sliding garage-style barriers to close their businesses at the end of the day. -

Washington DC Hike

HISTORIC D.C. MALL HIKE SATELLITE VIEW OF HIKE 2 Waypoints with bathroom facilities are in to start or end the hike and is highly the left (south side) far sidewalk until you ITALIC. Temporary changes or notes are recommended. The line for the tour can see a small white dome a third of the way in bold. be pretty long. If it’s too long when you and 300 feet to the south. Head to that first go by, plan to include it towards the dome. BEGINNING THE HIKE end of the day. Parking can be quite a challenge. It is OR recommended to park in a garage and GPS Start Point: take public transportation to reach The 27°36’52.54”N 82°44’6.39”W Head south of the WWII Memorial Mall. until you see a parking area and a small Challenge title building. Follow the path past the bus Union Station is a great place to find Circle Up! loading area and then head east. About parking and the building itself is a must 2300 feet to the left will be a small white see! The address is: 50 Massachusetts Challenge description domed structure. Head towards it. Avenue NE. Parking costs under $20 How many flagpoles surround the per car. For youth groups, take the Metro base of the Washington Monument? GPS to next waypoint since that can be a new and interesting _____________________________ 38°53’15.28”N 77° 2’36.50”W experience for them. The station you want is Metro Center station. -

Individual Projects

PROJECTS COMPLETED BY PROLOGUE DC HISTORIANS Mara Cherkasky This Place Has A Voice, Canal Park public art project, consulting historian, http://www.thisplacehasavoice.info The Hotel Harrington: A Witness to Washington DC's History Since 1914 (brochure, 2014) An East-of-the-River View: Anacostia Heritage Trail (Cultural Tourism DC, 2014) Remembering Georgetown's Streetcar Era: The O and P Streets Rehabilitation Project (exhibit panels and booklet documenting the District Department of Transportation's award-winning streetcar and pavement-preservation project, 2013) The Public Service Commission of the District of Columbia: The First 100 Years (exhibit panels and PowerPoint presentations, 2013) Historic Park View: A Walking Tour (booklet, Park View United Neighborhood Coalition, 2012) DC Neighborhood Heritage Trail booklets: Village in the City: Mount Pleasant Heritage Trail (2006); Battleground to Community: Brightwood Heritage Trail (2008); A Self-Reliant People: Greater Deanwood Heritage Trail (2009); Cultural Convergence: Columbia Heights Heritage Trail (2009); Top of the Town: Tenleytown Heritage Trail (2010); Civil War to Civil Rights: Downtown Heritage Trail (2011); Lift Every Voice: Georgia Avenue/Pleasant Plains Heritage Trail (2011); Hub, Home, Heart: H Street NE Heritage Trail (2012); and Make No Little Plans: Federal Triangle Heritage Trail (2012) “Mount Pleasant,” in Washington at Home: An Illustrated History of Neighborhoods in the Nation's Capital (Kathryn Schneider Smith, editor, Johns Hopkins Press, 2010) Mount -

The NAACP and the Black Freedom Struggle in Baltimore, 1935-1975 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillm

“A Mean City”: The NAACP and the Black Freedom Struggle in Baltimore, 1935-1975 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By: Thomas Anthony Gass, M.A. Department of History The Ohio State University 2014 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Hasan Kwame Jeffries, Advisor Dr. Kevin Boyle Dr. Curtis Austin 1 Copyright by Thomas Anthony Gass 2014 2 Abstract “A Mean City”: The NAACP and the Black Freedom Struggle in Baltimore, 1935-1975” traces the history and activities of the Baltimore branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) from its revitalization during the Great Depression to the end of the Black Power Movement. The dissertation examines the NAACP’s efforts to eliminate racial discrimination and segregation in a city and state that was “neither North nor South” while carrying out the national directives of the parent body. In doing so, its ideas, tactics, strategies, and methods influenced the growth of the national civil rights movement. ii Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to the Jackson, Mitchell, and Murphy families and the countless number of African Americans and their white allies throughout Baltimore and Maryland that strove to make “The Free State” live up to its moniker. It is also dedicated to family members who have passed on but left their mark on this work and myself. They are my grandparents, Lucious and Mattie Gass, Barbara Johns Powell, William “Billy” Spencer, and Cynthia L. “Bunny” Jones. This victory is theirs as well. iii Acknowledgements This dissertation has certainly been a long time coming. -

Ledroit Park Historic Walking Tour Written by Eric Fidler, September 2016

LeDroit Park Historic Walking Tour Written by Eric Fidler, September 2016 Introduction • Howard University established in 1867 by Oliver Otis Howard o Civil War General o Commissioner of the Freedman’s Bureau (1865-74) § Reconstruction agency concerned with welfare of freed slaves § Andrew Johnson wasn’t sympathetic o President of HU (1869-74) o HU short on cash • LeDroit Park founded in 1873 by Amzi Lorenzo Barber and his brother-in-law Andrew Langdon. o Barber on the Board of Trustees of Howard Univ. o Named neighborhood for his father-in-law, LeDroict Langdon, a real estate broker o Barber went on to develop part of Columbia Heights o Barber later moved to New York, started the Locomobile car company, became the “asphalt king” of New York. Show image S • LeDroit Park built as a “romantic” suburb of Washington, with houses on spacious green lots • Architect: James McGill o Inspired by Andrew Jackson Downing’s “Architecture of Country Houses” o Idyllic theory of architecture: living in the idyllic settings would make residents more virtuous • Streets named for trees, e.g. Maple (T), Juniper (6th), Larch (5th), etc. • Built as exclusively white neighborhood in the 1870s, but from 1900 to 1910 became almost exclusively black, home of Washington’s black intelligentsia--- poets, lawyers, civil rights activists, a mayor, a Senator, doctors, professors. o stamps, the U.S. passport, two Supreme Court cases on civil rights • Fence war 1880s • Relationship to Howard Theatre 531 T Street – Originally build as a duplex, now a condo. Style: Italianate (low hipped roof, deep projecting cornice, ornate wood brackets) Show image B 525 T Street – Howard Theatre performers stayed here. -

IN HONOR of FRED GRAY: MAKING CIVIL RIGHTS LAW from ROSA PARKS to the TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY - Introduction

Case Western Reserve Law Review Volume 67 Issue 4 Article 10 2017 SYMPOSIUM: IN HONOR OF FRED GRAY: MAKING CIVIL RIGHTS LAW FROM ROSA PARKS TO THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY - Introduction Jonathan L. Entin Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Jonathan L. Entin, SYMPOSIUM: IN HONOR OF FRED GRAY: MAKING CIVIL RIGHTS LAW FROM ROSA PARKS TO THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY - Introduction, 67 Case W. Rsrv. L. Rev. 1025 (2017) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev/vol67/iss4/10 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Case Western Reserve Law Review by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. Case Western Reserve Law Review·Volume 67·Issue 4·2017 —Symposium— In Honor of Fred Gray: Making Civil Rights Law from Rosa Parks to the Twenty-First Century Introduction Jonathan L. Entin† Contents I. Background................................................................................ 1026 II. Supreme Court Cases ............................................................... 1027 A. The Montgomery Bus Boycott: Gayle v. Browder .......................... 1027 B. Freedom of Association: NAACP v. Alabama ex rel. Patterson ....... 1028 C. Racial Gerrymandering: Gomillion v. Lightfoot ............................. 1029 D. Constitutionalizing the Law of