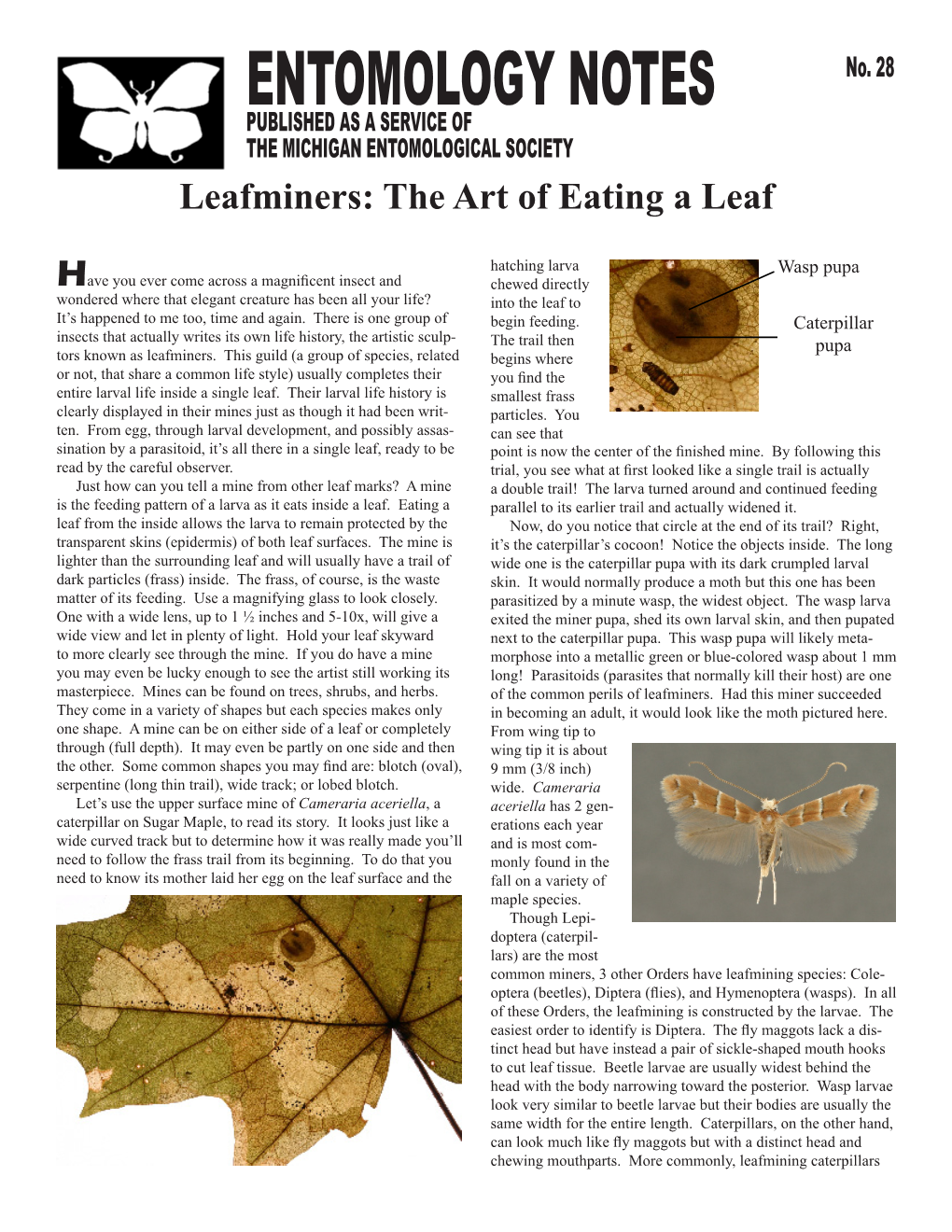

Leafminers: the Art of Eating a Leaf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PROCEEDINGS IUFRO Kanazawa 2003 INTERNATONAL

Kanazawa University PROCEEDINGS 21st-Century COE Program IUFRO Kanazawa 2003 Kanazawa University INTERNATONAL SYMPOSIUM Editors: Naoto KAMATA Andrew M. LIEBHOLD “Forest Insect Population Dan T. QUIRING Karen M. CLANCY Dynamics and Host Influences” Joint meeting of IUFRO working groups: 7.01.02 Tree Resistance to Insects 7.03.06 Integrated management of forest defoliating insects 7.03.07 Population dynamics of forest insects 14-19 September 2003 Kanazawa Citymonde Hotel, Kanazawa, Japan International Symposium of IUFRO Kanazawa 2003 “Forest Insect Population Dynamics and Host Influences” 14-19 September 2003 Kanazawa Citymonde Hotel, Kanazawa, Japan Joint meeting of IUFRO working groups: WG 7.01.02 "Tree Resistance to Insects" Francois LIEUTIER, Michael WAGNER ———————————————————————————————————— WG 7.03.06 "Integrated management of forest defoliating insects" Michael MCMANUS, Naoto KAMATA, Julius NOVOTNY ———————————————————————————————————— WG 7.03.07 "Population Dynamics of Forest Insects" Andrew LIEBHOLD, Hugh EVANS, Katsumi TOGASHI Symposium Conveners Dr. Naoto KAMATA, Kanazawa University, Japan Dr. Katsumi TOGASHI, Hiroshima University, Japan Proceedings: International Symposium of IUFRO Kanazawa 2003 “Forest Insect Population Dynamics and Host Influences” Edited by Naoto KAMATA, Andrew M. LIEBHOLD, Dan T. QUIRING, Karen M. CLANCY Published by Kanazawa University, Kakuma, Kanazawa, Ishikawa 920-1192, JAPAN March 2006 Printed by Tanaka Shobundo, Kanazawa Japan ISBN 4-924861-93-8 For additional copies: Kanazawa University 21st-COE Program, -

Taxonomic Studies on the Lithocolletinae of Japan (Lepidoptera : Gracillariidae) Part 2

Title Taxonomic studies on the Lithocolletinae of Japan (Lepidoptera : Gracillariidae) Part 2 Author(s) Kumata, Tosio Citation Insecta matsumurana, 26(1), 1-48 Issue Date 1963-08 Doc URL http://hdl.handle.net/2115/9698 Type bulletin (article) File Information 26(1)_p1-48.pdf Instructions for use Hokkaido University Collection of Scholarly and Academic Papers : HUSCAP TAXONOMIC STUDIES ON THE LITHOCOLLETINAE OF JAPAN (LEPIDOPTERA : GRACILLARIIDAE) Part Ill) By TOSIO KUMATA Entomological Institute, Faculty of Agriculture Hokkaido University, Sapporo In this part there are given twenty-nine species attacking Ulmaceae, Rosaceae, Legumi nosae, Aceraceae, Ericaceae and Caprifoliaceae, and two host-unknown species of the Lithocolletinae_ Moreover, two new genera are erected for the reception of four new species attacking Leguminosae_ 7_ Species attacking Ulmaceae 32. Lithocolletis tritorrhecta Meyrick (Fig. 1; 3, I-K) Lithocolletis tritorrhecta Meyrick, 1935, Exot. Microlep. 4 : 596; Issiki, 1950, Icon. Ins. Jap.: 454, f. 1224. Phyllonorycter tritorrhecta: Inoue, 1954, Check list Lep. Jap. 1 : 28. This species is represented by the aestival and autumnal forms, which are different III colour. Aestival form: 0 ((. Face silvery-white; palpus whitish, with a blackish streak on pos terior surface; tuft of head golden-ochreous, mixed with many whitish scales in centre; antenna white, each segment ringed with dark brown apically. Thorax golden-ochreous, with two white, wide lines running along inner margins of tegulae, and with a white, small spot at posterior angle. Legs whitish; fore tibia clouded inside; mid tibia with three oblique black streaks outside; all tarsi with black blotches or spots at base, basal 1/3, 3/5 and 4/5. -

Klicken, Um Den Anhang Zu Öffnen

Gredleria- VOL. 1 / 2001 Titelbild 2001 Posthornschnecke (Planorbarius corneus L.) / Zeichnung: Alma Horne Volume 1 Impressum Volume Direktion und Redaktion / Direzione e redazione 1 © Copyright 2001 by Naturmuseum Südtirol Museo Scienze Naturali Alto Adige Museum Natöra Südtirol Bindergasse/Via Bottai 1 – I-39100 Bozen/Bolzano (Italien/Italia) Tel. +39/0471/412960 – Fax 0471/412979 homepage: www.naturmuseum.it e-mail: [email protected] Redaktionskomitee / Comitato di Redazione Dr. Klaus Hellrigl (Brixen/Bressanone), Dr. Peter Ortner (Bozen/Bolzano), Dr. Gerhard Tarmann (Innsbruck), Dr. Leo Unterholzner (Lana, BZ), Dr. Vito Zingerle (Bozen/Bolzano) Schriftleiter und Koordinator / Redattore e coordinatore Dr. Klaus Hellrigl (Brixen/Bressanone) Verantwortlicher Leiter / Direttore responsabile Dr. Vito Zingerle (Bozen/Bolzano) Graphik / grafica Dr. Peter Schreiner (München) Zitiertitel Gredleriana, Veröff. Nat. Mus. Südtirol (Acta biol. ), 1 (2001): ISSN 1593 -5205 Issued 15.12.2001 Druck / stampa Gredleriana Fotolito Varesco – Auer / Ora (BZ) Gredleriana 2001 l 2001 tirol Die Veröffentlichungsreihe »Gredleriana« des Naturmuseum Südtirol (Bozen) ist ein Forum für naturwissenschaftliche Forschung in und über Südtirol. Geplant ist die Volume Herausgabe von zwei Wissenschaftsreihen: A) Biologische Reihe (Acta Biologica) mit den Bereichen Zoologie, Botanik und Ökologie und B) Erdwissenschaftliche Reihe (Acta Geo lo gica) mit Geologie, Mineralogie und Paläontologie. Diese Reihen können jährlich ge mein sam oder in alternierender Folge erscheinen, je nach Ver- fügbarkeit entsprechender Beiträge. Als Publikationssprache der einzelnen Beiträge ist Deutsch oder Italienisch vorge- 1 Naturmuseum Südtiro sehen und allenfalls auch Englisch. Die einzelnen Originalartikel erscheinen jeweils Museum Natöra Süd Museum Natöra in der eingereichten Sprache der Autoren und sollen mit kurzen Zusammenfassun- gen in Englisch, Italienisch und Deutsch ausgestattet sein. -

1997 Isbn #: 0-921631-18-9

TORONTO ENTOMOLOGISTS ASSOCIATION Publication # 30 - 98 Butterflies of Ontario & Summaries of Lepidoptera Encountered in Ontario in 1997 ISBN #: 0-921631-18-9 BUTTERFLIES OF ONTARIO & SUMMARIES OF LEPIDOPTERA ENCOUNTERED IN ONTARIO IN 1997 COMPILED BY ALAN J. HANKS PRODUCTION BY ALAN J. HANKS JUNE 1998 CONTENTS PAGE 1. INTRODUCTION 1 2. WEATHER DURING THE 1997 SEASON 5 3. CORRECTIONS TO PREVIOUS T.E.A. SUMMARIES 5 4. SPECIAL NOTES ON ONTARIO LEPIDOPTERA 6 4.1 Identification & Distribution ofOntario Crescent Butterflies Paul M. Catting 6 4.2 List ofButterflies seen in the Toronto Area & General Status Report - Barry Harrison & Joseph Jones 8 4.3 The Bog Elfin (Callophrys lanoraiensis) in Ontario P.M. Catling, R.A. Layberry, J.P. Crolla & J.D. Lafontaine 10 4.4 Butterflies ofPelee Island - Robert Bowles 14 4.5 Rearing Notes from Northumberland County - Dr. W.J.D. Eberlie 15 4.6 Catocala gracilis Grote (Graceful Underwing): New to Ontario - W.G. Lamond 16 4.7 Psaphida grandis (Gray Sallow): New to Ontario and Canada - W.G. Lamond 17 4.8 Butterflies ofAlgonquin Park - Colin D. Jones 18 4.9 The 500th Noctuid - Ken Stead 21 4.10 Occurences ofNoctua pronuba - Barry Harrison 22 4.11 Observations on Lepidoptera Predation - Tim Sabo 22 5. GENERAL SUMMARY - Alan J. Hanks 24 6. 1997 SUMMARY OF ONTARIO BUTTERFLIES compiled by Alan J. Hanks 25 Hesperiidae 25 Papilionidae 33 Pieridae 35 Lycaenidae 38 Libytheidae 44 Nymphalidae 44 Apaturidae 52 Satyridae 52 Danaidae 55 7. SELECTED REPORTS OF MOTHS IN ONTARIO, 1997 compiled by Dr. Duncan Robertson 56 8. CONCISE CYCLICAL SUMMARY OF MOTHS IN ONTARIO compiled by Dr. -

Impacts of Native and Non-Native Plants on Urban Insect Communities: Are Native Plants Better Than Non-Natives?

Impacts of Native and Non-native plants on Urban Insect Communities: Are Native Plants Better than Non-natives? by Carl Scott Clem A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Auburn University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Science Auburn, Alabama December 12, 2015 Key Words: native plants, non-native plants, caterpillars, natural enemies, associational interactions, congeneric plants Copyright 2015 by Carl Scott Clem Approved by David Held, Chair, Associate Professor: Department of Entomology and Plant Pathology Charles Ray, Research Fellow: Department of Entomology and Plant Pathology Debbie Folkerts, Assistant Professor: Department of Biological Sciences Robert Boyd, Professor: Department of Biological Sciences Abstract With continued suburban expansion in the southeastern United States, it is increasingly important to understand urbanization and its impacts on sustainability and natural ecosystems. Expansion of suburbia is often coupled with replacement of native plants by alien ornamental plants such as crepe myrtle, Bradford pear, and Japanese maple. Two projects were conducted for this thesis. The purpose of the first project (Chapter 2) was to conduct an analysis of existing larval Lepidoptera and Symphyta hostplant records in the southeastern United States, comparing their species richness on common native and alien woody plants. We found that, in most cases, native plants support more species of eruciform larvae compared to aliens. Alien congener plant species (those in the same genus as native species) supported more species of larvae than alien, non-congeners. Most of the larvae that feed on alien plants are generalist species. However, most of the specialist species feeding on alien plants use congeners of native plants, providing evidence of a spillover, or false spillover, effect. -

Forest Insect and Disease Conditions in Vermont 2008 Or in Separate Summaries for Sugarbush and Christmas Tree Managers

FOREST INSECT AND DISEASE CONDITIONS IN VERMONT 2008 AGENCY OF NATURAL RESOURCES DEPARTMENT OF FORESTS, PARKS & RECREATION WATERBURY VERMONT 05671-0601 STATE OF VERMONT JAMES DOUGLAS, GOVERNOR AGENCY OF NATURAL RESOURCES JONATHAN WOOD, SECRETARY DEPARTMENT OF FORESTS, PARKS & RECREATION Jason Gibbs, Commissioner Steven Sinclair, Director http://www.vtfpr.org/ We gratefully acknowledge the financial and technical support provided by the USDA Forest Service, Northeastern Area State and Private Forestry that enables us to conduct the surveys and publish the results in this report. This report serves as the final report for fulfillment of the Cooperative Lands – Survey and Technical Assistance and Forest Health Monitoring programs. FOREST INSECT AND DISEASE CONDITIONS IN VERMONT CALENDAR YEAR 2008 Hemlock Woolly Adelgid Egg Sac PREPARED BY: Kathleen Decker, Scott Pfister, Barbara Burns, Ronald Kelley, Trish Hanson, Sandra Wilmot AGENCY OF NATURAL RESOURCES DEPARTMENT OF FORESTS, PARKS & RECREATION TABLE OF CONTENTS Forest Resource Protection Personnel............................................................................ 1 Vermont 2008 Forest Insect and Disease Highlights ......................................................2 Vermont 2008 Forest Health Management Recommendations.......................................4 Introduction ...................................................................................................................6 Acknowledgments...........................................................................................................6 -

The Genetic Background of Three Introduced Leaf Miner Moth

Proccedings: IUFRO Kanazawa 2003 "Forest Insect Population Dynamics and Host Influences” - 67 - The Genetic Background of Three Introduced Leaf Miner Moth Species - Parectopa robiniella Clemens 1863, Phyllonorycter robiniella Clemens 1859 and Cameraria ohridella Deschka et Dimic 1986 Ferenc LAKATOS, Zoltán KOVÁCS Institute of Forest and Wood Protection, West-Hungarian University, Sopron, 9400, HUNGARY Christian STAUFFER Department of Forest- & Soil Sciences, University of Natural Resources & Applied Life Sciences (BOKU), Vienna, 1190, AUSTRIA Marc KENIS CABI Bioscience Centre, Delemont, 2800, SWITZERLAND Rumen TOMOV Department of Plant Protection, University of Forestry, Sofia, 1756, BULGARIA Donald R. DAVI S National Museum of Natural History, Washington D.C., 20560-0127, USA Abstract – North American and European populations of three Phyllonorycter robiniella Clemens 1859 and C) Cameraria invasive leaf miner moth species Parectopa robiniella Clemens ohridella Deschka et Dimic 1986 1863, Phyllonorycter robiniella Clemens 1859 and Cameraria ohridella Deschka et Dimic 1986 were investigated using mtDNA Taxonomic background sequences and PCR-RAPD. Significant variation (0.7%) in the All three, invasive, leaf-mining species are members of the mtDNA was detected among Parectopa robiniella population, allowing differentiation of European from North-American Gracillariidae (superfamily Gracillarioidea), a large, populations In the other two species, Phyllonorycter robiniella cosmopolitan family of over 2000 recognised species, with and C. ohridella, no substitutions could be detected among the probably an even greater number of species awaiting populations. The complementary PCR-RAPD analysis in C. discovery. The genus Parectopa is a member of the largest, ohridella revealed genetic similarities among populations that but far most diverse subfamily, Gracillariinae. The genera reflected historical patterns of spread. -

An All-Taxa Biodiversity Inventory of the Huron Mountain Club

AN ALL-TAXA BIODIVERSITY INVENTORY OF THE HURON MOUNTAIN CLUB Version: August 2016 Cite as: Woods, K.D. (Compiler). 2016. An all-taxa biodiversity inventory of the Huron Mountain Club. Version August 2016. Occasional papers of the Huron Mountain Wildlife Foundation, No. 5. [http://www.hmwf.org/species_list.php] Introduction and general compilation by: Kerry D. Woods Natural Sciences Bennington College Bennington VT 05201 Kingdom Fungi compiled by: Dana L. Richter School of Forest Resources and Environmental Science Michigan Technological University Houghton, MI 49931 DEDICATION This project is dedicated to Dr. William R. Manierre, who is responsible, directly and indirectly, for documenting a large proportion of the taxa listed here. Table of Contents INTRODUCTION 5 SOURCES 7 DOMAIN BACTERIA 11 KINGDOM MONERA 11 DOMAIN EUCARYA 13 KINGDOM EUGLENOZOA 13 KINGDOM RHODOPHYTA 13 KINGDOM DINOFLAGELLATA 14 KINGDOM XANTHOPHYTA 15 KINGDOM CHRYSOPHYTA 15 KINGDOM CHROMISTA 16 KINGDOM VIRIDAEPLANTAE 17 Phylum CHLOROPHYTA 18 Phylum BRYOPHYTA 20 Phylum MARCHANTIOPHYTA 27 Phylum ANTHOCEROTOPHYTA 29 Phylum LYCOPODIOPHYTA 30 Phylum EQUISETOPHYTA 31 Phylum POLYPODIOPHYTA 31 Phylum PINOPHYTA 32 Phylum MAGNOLIOPHYTA 32 Class Magnoliopsida 32 Class Liliopsida 44 KINGDOM FUNGI 50 Phylum DEUTEROMYCOTA 50 Phylum CHYTRIDIOMYCOTA 51 Phylum ZYGOMYCOTA 52 Phylum ASCOMYCOTA 52 Phylum BASIDIOMYCOTA 53 LICHENS 68 KINGDOM ANIMALIA 75 Phylum ANNELIDA 76 Phylum MOLLUSCA 77 Phylum ARTHROPODA 79 Class Insecta 80 Order Ephemeroptera 81 Order Odonata 83 Order Orthoptera 85 Order Coleoptera 88 Order Hymenoptera 96 Class Arachnida 110 Phylum CHORDATA 111 Class Actinopterygii 112 Class Amphibia 114 Class Reptilia 115 Class Aves 115 Class Mammalia 121 INTRODUCTION No complete species inventory exists for any area. -

Gredleriana Vol

Gredleriana Vol. 1 / 2001 pp. 9 – 81 Neue Erkenntnisse und Untersuchungen über die Roßkastanien-Miniermotte Cameraria ohridella Deschka & Dimic, 1986 (Lepidoptera, Gracillariidae)* Klaus Hellrigl** Abstract New Knowledge and Research on the Horse-Chestnut Leafminer Cameraria ohridella Deschka & Dimic, 1986. The present paper tries to give a comprehensive survey of the horse-chestnut-leafminer C. ohridella by interdisciplinary views and analysis of the host plant range (geography and system of plants) and special circumstances of the leafminer (distribution, affinity, parasitism, occurence of generations). The rapid expansion of C. ohridella in the various countries of central and Southern Europe is ex- plained; in Italy, where the introduction of the leafminer took place in 1994/95 via South Tyrol [central North] and Julian Venetia [North-East], the entire northern region (north of the 44th degree latitude) has already been attacked. The question of the host plants of C. ohridella is analysed and discussed: the leafminer attacks mainly the European horse-chestnut Aesculus hippocastanum, occasionally and to a much lower degree also the sycamore Acer pseudoplatanus; on the other hand, American buckeyes are largely attack-resistant. The relationship between the single species of Genus Aesculus and Genus Acer and their suitability as host-plants for Cameraria are discussed. By comparison of the structures of genitalia it is proved that there is a close relationship with a Cameraria species from Japan, C. niphonica Kumata, that lives on Acer spp. and must be regarded as a sister species of the South-East-European C. ohridella. On the other hand, there is no relationship with the North-American Cameraria species, not even with C. -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8,734,869 B2 Enan (45) Date of Patent: May 27, 2014

USOO8734869B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8,734,869 B2 Enan (45) Date of Patent: May 27, 2014 (54) SYNERGISTIC PEST CONTROL 5,942,214 A 8, 1999 Lucas et al. COMPOSITIONS 6,177.465 B1* 1/2001 Tanaka .......................... 514,535 6,238,682 B1 5, 2001 Klofta et al. 6,849,614 B1* 2/2005 Bessette et al. ................. 514/72 (75) Inventor: Essam Enan, Davis, CA (US) 7,541,155 B2 6/2009 Enan 7,622,269 B2 11/2009 Enan (73) Assignee: TyraTech, Inc., Melbourne, FL (US) 2003/0194454 A1* 10, 2003 Bessette et al. ............... 424,745 2006, 0083763 A1 4/2006 Neale et al. (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this 2006/0263.403 A1 11/2006 Enan patent is extended or adjusted under 35 2008.0075796 A1 3/2008 Enan U.S.C. 154(b) by 445 days. OTHER PUBLICATIONS (21) Appl. No.: 12/532,604 Colby, S.R., "Calculating Synergistic and Antagonistic Responses of Herbicide Combinations.” Weeds 15(1), p. 20-22, 1967. (22) PCT Filed: Mar. 21, 2008 James, et al. “Field-testing of methyl salicylate for recruitment and retention of beneficial insects in grapes and hops.” Journal of Chemi (86). PCT No.: PCT/US2008/003722 cal Ecology 30(8), p. 1613-1628, 2004. Lynn, D.E., “Development and characterization of insect cell lines.” S371 (c)(1), Cytotechnology 20, p. 3-11, 1996. (2), (4) Date: May 3, 2010 Lynn, D.E., "Methods for maintaining insect cell cultures,” J. Insect Science 2.9, p. 1-6, 2002. (87) PCT Pub. -

Leaf Mining Insects and Their Parasitoids in the Old-Growth Forest of the Huron Mountains

The Great Lakes Entomologist Volume 52 Numbers 3 & 4 - Fall/Winter 2019 Numbers 3 & Article 9 4 - Fall/Winter 2019 February 2020 Leaf Mining Insects and Their Parasitoids in the Old-Growth Forest of the Huron Mountains Ronald J. Priest Michigan State University, [email protected] Robert R. Kula Agricultural Research Service, United States Department of Agriculture, [email protected] Michael W. Gates Agricultural Research Service, United States Department of Agriculture, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/tgle Part of the Entomology Commons Recommended Citation Priest, Ronald J.; Kula, Robert R.; and Gates, Michael W. 2020. "Leaf Mining Insects and Their Parasitoids in the Old-Growth Forest of the Huron Mountains," The Great Lakes Entomologist, vol 52 (2) Available at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/tgle/vol52/iss2/9 This Peer-Review Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Biology at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Great Lakes Entomologist by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. Leaf Mining Insects and Their Parasitoids in the Old-Growth Forest of the Huron Mountains Cover Page Footnote The first author is most thankful ot David Gosling, former Huron Mountain Wildlife Foundation (HMWF) Director, for approving the initial proposal to survey leaf mining insects, guidance to various habitats, and encouragement to continue surveying even when recoveries were at first unexpectedly ewf . Kerry Woods (Bennington College, Vermont), current HMWF Director, is also sincerely thanked for his continued support and patience with this work. -

Zootaxa, Pholetesor Mason

ZOOTAXA 1144 Revision of the Nearctic species of the genus Pholetesor Mason (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) JAMES B. WHITFIELD Magnolia Press Auckland, New Zealand JAMES B. WHITFIELD Revision of the Nearctic species of the genus Pholetesor Mason (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) (Zootaxa 1144) 94 pp.; 30 cm. 10 Mar. 2006 ISBN 1-877407-56-9 (paperback) ISBN 1-877407-57-7 (Online edition) FIRST PUBLISHED IN 2006 BY Magnolia Press P.O. Box 41383 Auckland 1030 New Zealand e-mail: [email protected] http://www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ © 2006 Magnolia Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, transmitted or disseminated, in any form, or by any means, without prior written permission from the publisher, to whom all requests to reproduce copyright material should be directed in writing. This authorization does not extend to any other kind of copying, by any means, in any form, and for any purpose other than private research use. ISSN 1175-5326 (Print edition) ISSN 1175-5334 (Online edition) Zootaxa 1144: 1–94 (2006) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ ZOOTAXA 1144 Copyright © 2006 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) Revision of the Nearctic species of the genus Pholetesor Mason (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) JAMES B. WHITFIELD Department of Entomology, University of Illinois, Urbana, IL 61801 USA. E-mail: [email protected] Table of contents Abstract ............................................................................................................................................