Visualizing Christian Marriage in the Roman World by Mark D. Ellison

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Praying with Body, Mind, and Voice

Praying with Body, Mind, and Voice n the celebration of Mass we raise our hearts and SITTING minds to God. We are creatures of body as well as Sitting is the posture of listening and meditation, so the Ispirit, so our prayer is not confined to our minds congregation sits for the pre-Gospel readings and the and hearts. It is expressed by our bodies as well. homily and may also sit for the period of meditation fol- When our bodies are engaged in our prayer, we pray lowing Communion. All should strive to assume a seated with our whole person. Using our entire being in posture during the Mass that is attentive rather than prayer helps us to pray with greater attentiveness. merely at rest. During Mass we assume different postures— standing, kneeling, sitting—and we are also invited PROCESSIONS to make a variety of gestures. These postures and gestures are not merely ceremonial. They have pro- Every procession in the Liturgy is a sign of the pilgrim found meaning and, when done with understand- Church, the body of those who believe in Christ, on ing, can enhance our participation in the Mass. their way to the Heavenly Jerusalem. The Mass begins with the procession of the priest and ministers to the altar. The Book of the Gospels is carried in procession to the ambo. The gifts of bread and wine are brought STANDING forward to the altar. Members of the assembly come for- Standing is a sign of respect and honor, so we stand as ward in procession—eagerly, attentively, and devoutly— the celebrant who represents Christ enters and leaves to receive Holy Communion. -

Eunuchs in the East, Men in the West? 147

Eunuchs in the East, Men in the West? 147 Chapter 8 Eunuchs in the East, Men in the West? Dis/unity, Gender and Orientalism in the Fourth Century Shaun Tougher Introduction In the narrative of relations between East and West in the Roman Empire in the fourth century AD, the tensions between the eastern and western imperial courts at the end of the century loom large. The decision of Theodosius I to “split” the empire between his young sons Arcadius and Honorius (the teenage Arcadius in the east and the ten-year-old Honorius in the west) ushered in a period of intense hostility and competition between the courts, famously fo- cused on the figure of Stilicho.1 Stilicho, half-Vandal general and son-in-law of Theodosius I (Stilicho was married to Serena, Theodosius’ niece and adopted daughter), had been left as guardian of Honorius, but claimed guardianship of Arcadius too and concomitant authority over the east. In the political manoeu- vrings which followed the death of Theodosius I in 395, Stilicho was branded a public enemy by the eastern court. In the war of words between east and west a key figure was the (probably Alexandrian) poet Claudian, who acted as a ‘pro- pagandist’ (through panegyric and invective) for the western court, or rather Stilicho. Famously, Claudian wrote invectives on leading officials at the eastern court, namely Rufinus the praetorian prefect and Eutropius, the grand cham- berlain (praepositus sacri cubiculi), who was a eunuch. It is Claudian’s two at- tacks on Eutropius that are the inspiration and central focus of this paper which will examine the significance of the figure of the eunuch for the topic of the end of unity between east and west in the Roman Empire. -

The Marriage Contract in Fine Art

The Marriage Contract in Fine Art BENJAMIN A. TEMPLIN* I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................ 45 II. THE ARTIST'S INTERPRETATION OF LAW ...................................... 52 III. THE ARNOLFINI MARRIAGE: CLANDESTINE MARRIAGE CEREMONY OR BETROTHAL CONTRACT? .............................. ........................ .. 59 IV. PRE-CONTRACTUAL SEX AND THE LAWYER AS PROBLEM SOLVER... 69 V. DOWRIES: FOR LOVE OR MONEY? ........................ ................ .. .. 77 VI. WILLIAM HOGARTH: SATIRIC INDICTMENT OF ARRANGED MARRIAGES ...................................................................................... 86 VII. GREUZE: THE CIVIL MARRIAGE CONTRACT .................................. 93 VIII.NINETEENTH AND TWENTIETH CENTURY COMPARISONS ................ 104 LX . C ONCLUSION ..................................................................................... 106 I. INTRODUCTION From the Middle Ages to the Enlightenment, several European and English artists produced paintings depicting the formation of a marriage contract.' The artwork usually portrays a couple-sometimes in love, some- * Associate Professor, Thomas Jefferson School of Law. For their valuable assis- tance, the author wishes to thank Susan Tiefenbrun, Chris Rideout, Kathryn Sampson, Carol Bast, Whitney Drechsler, Ellen Waldman, David Fortner, Sandy Contreas, Jane Larrington, Julie Kulas, Kara Shacket, and Dessa Kirk. The author also thanks the organizers of the Legal Writing Institute's 2008 Summer Writing Workshop -

{Download PDF} High Five with Julius

HIGH FIVE WITH JULIUS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Paul Frank | 10 pages | 24 Feb 2010 | CHRONICLE BOOKS | 9780811871471 | English | California, United States High Five with Julius PDF Book Rate this:. My 3-year-old loved giving each character a high-five and then her hand would linger as she felt the different textures. English On Shelf. How Can We Help? As two-way G-League point guard Kadeem Allen bounced away the final seconds, a large throng of Knicks fans stood up and roared as the club moved to Big Deal, Baby. McGraw Hill. Nice Partner! Randle and others talked about a lack of focus at the morning shootaround Monday. You are commenting using your WordPress. Table of Contents. Universal Conquest Wiki. Smiling this much is so heartwarming! It did the trick. On Shelf. I think focusing primarily on the individual is definitely the first step. A medical study found that fist bumps and high fives spread fewer germs than handshakes. Welcome to another Write a Review Wednesday , a meme started by Tara Lazar as a way to show support to authors of kids literature. Each spread encourages kids to celebrate amazing everyday achievementsfrom sharing their toys to just being themselvesand features a touch-and-feel texture that will keep little ones engaged as they strive to be and do their very best. Redirected from High-five. National High Five Day is a project to give out high fives and is typically held on the third Thursday in April. Categories : introductions American cultural conventions Hand gestures. By continuing to use this website, you agree to their use. -

DECEMBER 08 Doing Business Globally Requires More Than Compliance with Legal Mandates

ows When stepping into a foreign country, be sure to start on the right foot. DECEMBER 08 Doing business globally requires more than compliance with legal mandates. Knowledge of local customs is also critical, especially when making a first impression. A monthly best practices alert for multinationals confronting the As 2008 draws to a close (none too soon), and we all look forward to greeting the New challenges of the global workplace Year, we offer some tips on how to say hello in countries around the world. This Month’s With best wishes from the International Labor Group. Challenge When doing business abroad, Hugs and Business Gestures/ not knowing the local customs Country Handshake Eye Contact Other Kisses Cards Physical Space can lead to serious embarrassment. EUROPE UK A handshake Generally Customs Avoid Direct eye Pants actually Best Practice is the most no kissing similar to excessive hand contact is means appropriate or hugging. U.S. gestures and common and underwear, not Tip of the Month greeting. displays of acceptable, but trousers. emotion. don’t be too A little preparation can prevent intense. a lot of trouble. Get to know France A handshake In social Cards The U.S. sign Direct eye Always apologize the local customs before is the most settings, should be for ok means contact is if you do not embarking for an international appropriate friends do printed in zero in France. common and speak French business meeting. greeting and les bises English acceptable, and or if you need to farewell. (touching on one sometimes conduct business However, cheeks and side and intense. -

Rome of the Pilgrims and Pilgrimage to Rome

58 CHAPTER 2 Rome of the pilgrims and pilgrimage to Rome 2.1 Introduction As noted, the sacred topography of early Christian Rome focused on different sites: the official Constantinian foundations and the more private intra-mural churches, the tituli, often developed and enlarged under the patronage of wealthy Roman families or popes. A third, essential category is that of the extra- mural places of worship, almost always associated with catacombs or sites of martyrdom. It is these that will be examined here, with a particular attention paid to the documented interaction with Anglo-Saxon pilgrims, providing insight to their visual experience of Rome. The phenomenon of pilgrims and pilgrimage to Rome was caused and constantly influenced by the attitude of the early-Christian faithful and the Church hierarchies towards the cult of saints and martyrs. Rome became the focal point of this tendency for a number of reasons, not least of which was the actual presence of so many shrines of the Apostles and martyrs of the early Church. Also important was the architectural manipulation of these tombs, sepulchres and relics by the early popes: obviously and in the first place this was a direct consequence of the increasing number of pilgrims interested in visiting the sites, but it seems also to have been an act of intentional propaganda to focus attention on certain shrines, at least from the time of Pope Damasus (366-84).1 The topographic and architectonic centre of the mass of early Christian Rome kept shifting and moving, shaped by the needs of visitors and ‒ at the same time ‒ directing these same needs towards specific monuments; the monuments themselves were often built or renovated following a programme rich in liturgical and political sub-text. -

How Body Language Can Help--Or Hurt--How You Lead

Table Of Contents Title Page Copyright More praise for The Silent Language of Leaders Introduction Oh, the Things I've Seen! The Time Is Right Chapter Outline From Good to Outstanding Chapter 1: Leadership at a Glance Your Three Brains Wired for Body Language The Eye of the Beholder Personal Curb Appeal Five Mistakes People Make Reading Your Body Language When Your Body Doesn't Match Your Words The Body Language of a Great Leader Chapter Two: Negotiation Four Tips for Reading Body Language Are They with You or Against You? Dealing with the Disengaged Are They Bluffing? Body Language Guidelines for Negotiators Chapter 3: Leading Change This Is Your Brain on Change The Body-Mind Connection Announcing Change What Do People Want from You? The Power of Empathy Chapter 4: Collaboration The Universal Need for Collaboration Wired to Connect Six Body Language Tips for Inclusion The Importance of How You Say What You Say Using Space Dress for Success What Your Office Says About You Familiarity Breeds Collaboration Chapter 5: Communicating Virtually and Face-to- Face Technology, the Great Enabler Six Tips for a Conference Call Important Tips for Videoconferencing Technology Brings a New Range of Communication Options What's So Great About Face-to-Face? Chapter 6: He Leads, She Leads The Neuroscience of Gender Why Jane Doesn't Lead Thirteen Gender-Based Differences in Nonverbal Communication Leadership Styles of Men and Women The Body Language of Male and Female Leaders Body Language Tips for Male and Female Leaders Men Are from Mars, Women Are from -

The Routledge Handbook of Early Christian Art Christian Sarcophagi

This article was downloaded by: 10.3.98.104 On: 29 Sep 2021 Access details: subscription number Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: 5 Howick Place, London SW1P 1WG, UK The Routledge Handbook of Early Christian Art Robin M. Jensen, Mark D. Ellison Christian Sarcophagi from Rome Publication details https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9781315718835-3 Jutta Dresken-Weiland Published online on: 20 May 2018 How to cite :- Jutta Dresken-Weiland. 20 May 2018, Christian Sarcophagi from Rome from: The Routledge Handbook of Early Christian Art Routledge Accessed on: 29 Sep 2021 https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9781315718835-3 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR DOCUMENT Full terms and conditions of use: https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/legal-notices/terms This Document PDF may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproductions, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The publisher shall not be liable for an loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. 3 CHRISTIAN SARCOPHAGI FROM ROME Jutta Dresken-Weiland Because they are so numerous, Christian sarcophagi from Rome are the most important group of objects for the creation and invention of a Christian iconography. -

Marriage in the 21St Century: from a State of Confusion to a State of Being Gemma Margaret Anne Barriteau

Duquesne University Duquesne Scholarship Collection Electronic Theses and Dissertations Summer 1-1-2016 Marriage in the 21st Century: From a State of Confusion to a State of Being Gemma Margaret Anne Barriteau Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/etd Recommended Citation Barriteau, G. (2016). Marriage in the 21st Century: From a State of Confusion to a State of Being (Doctoral dissertation, Duquesne University). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/etd/88 This One-year Embargo is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LIVED EXPERIENCES OF MARRIAGE IN THE 21ST CENTURY: FROM A STATE OF CONFUSION TO A STATE OF BEING A Dissertation Submitted to the School of Education Duquesne University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Gemma M. Barriteau August 2016 Copyright by Gemma M. Barriteau 2016 DUQUESNE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF EDUCATION Department of Counseling, Psychology and Special Education Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) Executive Counselor Education and Supervision Program Presented by: Gemma M. Barriteau B.A., Deviant Behavior & Social Control M.S.Ed., Community Mental Health Counseling August 2016 LIVED EXPERIENCES OF MARRIAGE IN THE 21ST CENTURY: FROM A STATE OF CONFUSION TO A STATE OF BEING Approved by: _____________________________________________, Chair Lisa Lopez Levers, Ph.D. Professor of Counselor Education Department of Counseling, Psychology, and Special Education School of Education Duquesne University ___________________________________________, Member James E. -

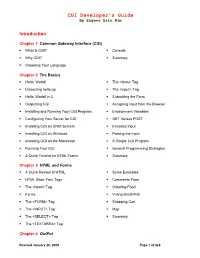

CGI Developer's Guide by Eugene Eric Kim

CGI Developer's Guide By Eugene Eric Kim Introduction Chapter 1 Common Gateway Interface (CGI) What Is CGI? Caveats Why CGI? Summary Choosing Your Language Chapter 2 The Basics Hello, World! The <form> Tag Dissecting hello.cgi The <input> Tag Hello, World! in C Submitting the Form Outputting CGI Accepting Input from the Browser Installing and Running Your CGI Program Environment Variables Configuring Your Server for CGI GET Versus POST Installing CGI on UNIX Servers Encoded Input Installing CGI on Windows Parsing the Input Installing CGI on the Macintosh A Simple CGI Program Running Your CGI General Programming Strategies A Quick Tutorial on HTML Forms Summary Chapter 3 HTML and Forms A Quick Review of HTML Some Examples HTML Basic Font Tags Comments Form The <head> Tag Ordering Food Forms Voting Booth/Poll The <FORM> Tag Shopping Cart The <INPUT> Tag Map The <SELECT> Tag Summary The <TEXTAREA> Tag Chapter 4 OutPut Revised January 20, 2009 Page 1 of 428 CGI Developer's Guide By Eugene Eric Kim Header and Body: Anatomy of Server Displaying the Current Date Response Server-Side Includes HTTP Headers On-the-Fly Graphics Formatting Output in CGI A "Counter" Example MIME Counting the Number of Accesses Location Text Counter Using Server-Side Includes Status Graphical Counter Other Headers No-Parse Header Dynamic Pages Summary Using Programming Libraries to Code CGI Output Chapter 5 Input Background cgi-lib.pl How CGI Input Works cgihtml Environment Variables Strategies Encoding -

The Sanctoral Calendar of Wilhelm Loehe's Martyrologium Trans

The Sanctoral Calendar of Wilhelm Loehe's Martyrologium trans. with an introduction by Benjamin T. G. Mayes October 2001 Source: Wilhelm Loehe, Martyrologium. Zur Erklärung der herkömmlichen Kalendernamen. (Nürnberg: Verlag von Gottfr. Löhe, 1868). Introduction. Loehe's Martyrologium of 1868 was not his first attempt at a Lutheran sanctoral calendar. Already in 1859, he had his Haus-, Schul- und Kirchenbuch für Christen des lutherischen Bekenntnisses printed, in which he included a sanctoral calendar which was different in many ways from his later, corrected version. The earlier calendar contained many more names, normally at least two names per day. Major feasts were labelled with their Latin names. But the earlier calendar also had errors. Many dates were marked with a question mark. A comparison of the two calendars shows that in the earlier calendar, Loehe had mistaken Cyprian the Sorcerer (Sept. 26) with Cyprian of Carthage. On the old calendar's April 13th, Hermenegild was a princess. In the new one, he's a prince. In the earlier calendar, Hildegard the Abbess (Sept. 17) was dated in the 300's. In the new one, she is dated 1179. In fact, in the later calendar, I would suppose that half of the dates have been changed. Loehe was conscious of the limitations of his calendar. He realized especially how difficult the selection of names was. His calendar contains the names of many Bavarian saints. This is to be expected, considering the fact that his parish, Neuendettelsau, is located in Bavaria. Loehe gave other reasons for the selection of names in his Martyrologium: "The booklet follows the old calendar names. -

Introduction What’S Race Got to Do with It? Postwar German History in Context

After the Nazi Racial State: Difference and Democracy in Germany and Europe Rita Chin, Heide Fehrenbach, Geoff Eley, and Atina Grossmann http://www.press.umich.edu/titleDetailDesc.do?id=354212 The University of Michigan Press, 2009. Introduction What’s Race Got to Do With It? Postwar German History in Context Rita Chin and Heide Fehrenbach In June 2006, just prior to the start of the World Cup in Germany, the New York Times ran a front-page story on a “surge in racist mood” among Germans attending soccer events and anxious of‹cials’ efforts to discour- age public displays of racism before a global audience. The article led with the recent experience of Nigerian forward Adebowale Ogungbure, who, af- ter playing a match in the eastern German city of Halle, was “spat upon, jeered with racial remarks, and mocked with monkey noises” as he tried to exit the ‹eld. “In rebuke, he placed two ‹ngers under his nose to simulate a Hitler mustache and thrust his arm in a Nazi salute.”1 Although the press report suggested the contrary, the racist behavior directed at Ogungbure was hardly resurgent or unique. Spitting, slurs, and offensive stereotypes have a long tradition in the German—and broader Euro-American—racist repertoire. Ogungbure’s wordless gesture, more- over, gave the lie to racism as a worrisome product of the New Europe or even the new Germany. Rather, his mimicry ef‹ciently suggested continu- ity with a longer legacy of racist brutality reaching back to the Third Reich. In effect, his response to the antiblack bigotry of German soccer fans was accusatory and genealogically precise: it screamed “Nazi!” and la- beled their actions recidivist holdovers from a fanatical fascist past.