Why Busways? Styles of Planning and Mode-Choice Decision-Making in Brisbane's Transport Networks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Queensland Transport and Roads Investment Program (QTRIP) 2019-20 to 2022-23

Queensland Transport and Roads Investment Program 2019–20 to 2022–23 South Coast 6,544 km2 Area covered by district1 19.48% Beenleigh LOGAN 1 CITY Population of Queensland COUNCIL 919 km Jimboomba Oxenford Other state-controlled road network (Helensvale light rail station) Fassifern SOUTHPORT NERANG 130 km SURFERS Beaudesert Boonah PARADISE National Land Transport Network (Broadbeach SCENIC RIM light rail station) REGIONAL COUNCIL Mudgeeraba 88 km GOLD COAST National rail network CITY Coolangatta COUNCIL 1Queensland Government Statistician’s Office (Queensland Treasury) Queensland Regional Profiles. www.qgsa.gld.gov.auwww.qgso.qld.gov.au (retrieved 1626 AprilMay 2019)2018) Legend National road network State strategic road network State regional and other district road National rail network 0 15 Km Other railway (includes light rail) Local government boundary Legend Nerang Office National road network 36-38 Cotton Street | Nerang | Qld 4211 State strategic road network PO Box 442 | Nerang | Qld 4211 State regional and other district road (07) 5563 6600 | [email protected] National rail network Other railway (includes light rail) Local government boundary Divider image: Construction worksworks onon thethe StapleyStapley RoadRoad bridge bridge at at Exit Exit 84 84 of of the Pacific Motorway at ReedyReedy Creek.Creek. District program highlights • business case development for safety and capacity • commence extending the four-lane duplication of upgrades at Exit 38 and 41 interchanges on the Pacific Mount Lindesay Highway between Rosia Road and In 2018–19 we completed: Motorway at Yatala Stoney Camp Road interchange at Greenbank • duplication of Waterford-Tamborine Road, from two to • business case development for the Mount Lindesay • commence construction of a four-lane upgrade of four lanes, between Anzac Avenue and Hotz Road at Highway four-lane upgrade between Stoney Camp Road Mount Lindesay Highway, between Camp Cable Road Logan Village and Chambers Flat Road interchanges. -

Gold Coast Rapid Transit

Gold Coast Rapid Transit 5 Project Staging Gold Coast Rapid Transit Concept Design Impact Management Plan Volume 2 Chapter 5 – Project Staging Contents 1. Staging of the Gold Coast Rapid Transit Project 3 1.1 Project Stages 3 1.2 Factors determining staging 4 1.3 Indicative staging plan 6 2. Project Life Cycle of the Gold Coast Rapid Transit Project 8 2.1 Pre-feasibility phase 8 2.2 Feasibility phase 9 2.3 Procurement phase 10 2.4 Construction phase 10 2.5 Commissioning phase 10 2.6 Operations phase 11 2.7 Future Staged Development 11 Table Index Table 5 – 1 Indicative Staging Plan 7 Figure Index Figure 5 – 1 Sections of the GCRT 4 Figure 5 – 2 Project Life Cycle Phases 9 Vol 2 Chp 5 -2 Gold Coast Rapid Transit Concept Design Impact Management Plan Volume 2 Chapter 5 – Project Staging 1. Staging of the Gold Coast Rapid Transit Project 1.1 Project Stages World class, high capacity public transport projects are often implemented in stages to enable the efficient matching of investment in infrastructure and services with demand and/or funding. A key consideration with the development of the GCRT Project has been the development of a Concept Design which can be implemented in stages. Whilst the South East Queensland Infrastructure Plan and Program (SEQIPP) 2008-2026 does not provide a detailed breakdown of the Project, SEQIPP 2007-2026 described the GCRT in two stages: Stage 1 from Helensvale to Broadbeach – to be completed by 2011; and Stage 2 from Broadbeach to Coolangatta – to be completed by 2015. -

SEB Case Study Report for QU

This may be the author’s version of a work that was submitted/accepted for publication in the following source: Widana Pathiranage, Rakkitha, Bunker, Jonathan M.,& Bhaskar, Ashish (2014) Case study : South East Busway (SEB), Brisbane, Australia. (Unpublished) This file was downloaded from: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/70498/ c Copyright 2014 The Author(s) This work is covered by copyright. Unless the document is being made available under a Creative Commons Licence, you must assume that re-use is limited to personal use and that permission from the copyright owner must be obtained for all other uses. If the docu- ment is available under a Creative Commons License (or other specified license) then refer to the Licence for details of permitted re-use. It is a condition of access that users recog- nise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. If you believe that this work infringes copyright please provide details by email to [email protected] Notice: Please note that this document may not be the Version of Record (i.e. published version) of the work. Author manuscript versions (as Sub- mitted for peer review or as Accepted for publication after peer review) can be identified by an absence of publisher branding and/or typeset appear- ance. If there is any doubt, please refer to the published source. Case Study: South East Busway (SEB), Brisbane, Australia CASE STUDY: SOUTH EAST BUSWAY (SEB), BRISBANE, AUSTRALIA By Rakkitha Widanapathiranage Jonathan M Bunker Ashish Bhaskar Civil Engineering and Built Environment School, Science and Engineering Faculty, Queensland University of Technology, Australia. -

Connecting SEQ 2031 an Integrated Regional Transport Plan for South East Queensland

Connecting SEQ 2031 An Integrated Regional Transport Plan for South East Queensland Tomorrow’s Queensland: strong, green, smart, healthy and fair Queensland AUSTRALIA south-east Queensland 1 Foreword Vision for a sustainable transport system As south-east Queensland's population continues to grow, we need a transport system that will foster our economic prosperity, sustainability and quality of life into the future. It is clear that road traffic cannot continue to grow at current rates without significant environmental and economic impacts on our communities. Connecting SEQ 2031 – An Integrated Regional Transport Plan for South East Queensland is the Queensland Government's vision for meeting the transport challenge over the next 20 years. Its purpose is to provide a coherent guide to all levels of government in making transport policy and investment decisions. Land use planning and transport planning go hand in hand, so Connecting SEQ 2031 is designed to work in partnership with the South East Queensland Regional Plan 2009–2031 and the Queensland Government's new Queensland Infrastructure Plan. By planning for and managing growth within the existing urban footprint, we can create higher density communities and move people around more easily – whether by car, bus, train, ferry or by walking and cycling. To achieve this, our travel patterns need to fundamentally change by: • doubling the share of active transport (such as walking and cycling) from 10% to 20% of all trips • doubling the share of public transport from 7% to 14% of all trips • reducing the share of trips taken in private motor vehicles from 83% to 66%. -

Characteristics of Bus Rapid Transit for Decision-Making

Project No: FTA-VA-26-7222-2004.1 Federal United States Transit Department of August 2004 Administration Transportation CharacteristicsCharacteristics ofof BusBus RapidRapid TransitTransit forfor Decision-MakingDecision-Making Office of Research, Demonstration and Innovation NOTICE This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the United States Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The United States Government assumes no liability for its contents or use thereof. The United States Government does not endorse products or manufacturers. Trade or manufacturers’ names appear herein solely because they are considered essential to the objective of this report. Form Approved REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188), Washington, DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave blank) 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES August 2004 COVERED BRT Demonstration Initiative Reference Document 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5. FUNDING NUMBERS Characteristics of Bus Rapid Transit for Decision-Making 6. AUTHOR(S) Roderick B. Diaz (editor), Mark Chang, Georges Darido, Mark Chang, Eugene Kim, Donald Schneck, Booz Allen Hamilton Matthew Hardy, James Bunch, Mitretek Systems Michael Baltes, Dennis Hinebaugh, National Bus Rapid Transit Institute Lawrence Wnuk, Fred Silver, Weststart - CALSTART Sam Zimmerman, DMJM + Harris 7. -

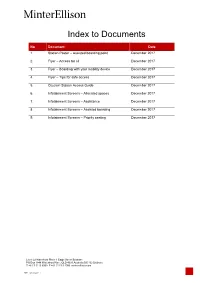

Index to Documents

Index to Documents No Document Date 1. Station Poster – Assisted boarding point December 2017 2. Flyer – Access for all December 2017 3. Flyer – Boarding with your mobility device December 2017 4. Flyer – Tips for safe access December 2017 5. Citytrain Station Access Guide December 2017 6. Infotainment Screens – Allocated spaces December 2017 7. Infotainment Screens – Assistance December 2017 8. Infotainment Screens – Assisted boarding December 2017 9. Infotainment Screens – Priority seating December 2017 Level 22 Waterfront Place 1 Eagle Street Brisbane PO Box 7844 Waterfront Place QLD 4001 Australia DX 102 Brisbane T +61 7 3119 6000 F +61 7 3119 1000 minterellison.com ME_143266442_1 Do you require assistance getting on or off the train? Please wait near the assisted boarding point and we will come to you. How it works • Boarding assistance may be provided by station staff present on the platform. • Alternatively, assistance will be provided by the train guard at the assisted boarding point. For further information Use the station help phone, the onboard emergency help button, text 0428 774 636 or call 13 16 17 Access for all If you need assistance getting on or off the train at any Citytrain station, just wait near the assisted boarding point and we will come to you. This point is indicated by a blue and white symbol for accessibility and is typically located near the middle of the platform. At many stations, the assisted boarding point will be located on a higher section of the platform to allow for easier access to and from the carriage. The assisted boarding point is also usually close to other access features such as the emergency and disability assistance phone, hearing aid loops, audio and visual timetable information and lifts. -

Translink Transit Authority | Final Report 1 July 2012 – 31 December 2012 Translink Transit Authority | Final Report

TransLink Transit Authority | Final Report 1 July 2012 – 31 December 2012 TransLink Transit Authority | Final Report TransLink Transit Authority 61 Mary Street Brisbane Q 4000 GPO Box 50, Brisbane Q 4001 Fax: (07) 3338 4600 Website: translink.com.au 28 March 2013 The Honourable Scott Emerson MP Minister for Transport and Main Roads GPO Box 2644 Brisbane Qld 4000 Dear Minister Emerson TransLink Transit Authority Final Report: Letter of Compliance I am pleased to present the Final Report and financial statements of the former TransLink Transit Authority and the TransLink Transit Authority Employing Office for the period 1 July 2012 to 31 December 2012. I certify that this annual report complies with: the prescribed requirements of the Financial Accountability Act 2009 and the Financial and Performance Management Standard 2009, and the detailed requirements set out in the Annual Report Requirements for Queensland Government Agencies. A checklist outlining the annual reporting requirements can be found on pages 112-113 of this annual report or accessed at translink.com.au. Yours sincerely Matthew Longland Acting Chief Executive Officer TransLink Transit Authority ii TransLink Transit Authority | Final Report About TransLink About this report Welcome to the TransLink Transit Authority Final Report. Following machinery-of-Government changes implemented on 2 August 2012, the TransLink Transit Authority was abolished, with its core functions transitioning to the Department of Transport and Main Roads. The Transport Operations (TransLink Transit Authority) Act 2008, under which TransLink was established, was repealed on 1 January 2013. As such, this report refers to the activities and performance of the TransLink Transit Authority for the period 1 July 2012 to 31 December 2012 only. -

The South East Transit Project LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY of QUEENSLAND

Report No. 39, July 1997 The South East Transit Project LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF QUEENSLAND PUBLIC WORKS COMMITTEE THE SOUTH EAST TRANSIT PROJECT Report No. 39 PUBLIC WORKS COMMITTEE MEMBERS Mr Len Stephan MLA (Chairman) Member for Gympie Mr Bill D’Arcy MLA (Deputy Chairman) Member for Woodridge Mr Graham Healy MLA Member for Toowoomba North Mr Pat Purcell MLA Member for Bulimba Mr Ted Radke MLA Member for Greenslopes Hon Geoff Smith MLA Member for Townsville SECRETARIAT Mr Les Dunn Research Director Ms Alison Wishart Research Officer Ms Maureen Barnes Executive Assistant CONTENTS Page PREFACE ............................................................................................................................ i RECOMMENDATIONS.................................................................................................... ii INTRODUCTION................................................................................................................1 THE COMMITTEE ...................................................................................................1 SCOPE OF INQUIRY................................................................................................2 SUBMISSIONS, INSPECTION AND HEARINGS ...................................................2 RESPONSIBILITY OF MINISTERS.........................................................................3 DESCRIPTION OF THE PROJECT .................................................................................4 WHAT IS A BUSWAY? ............................................................................................4 -

Case Studies on Transit Oriented Development Around Bus Rapid Transit Systems in North America and Australia

Bus Rapid Transit and Transit Oriented Development: Case Studies on Transit Oriented Development Around Bus Rapid Transit Systems in North America and Australia April 2008 Breakthrough Technologies Institute 1100 H St N.W. Suite 800 Washington, D.C. 20005 Contents 1 Acknowledgements ......................................................................................................................................... - 3 - 2 Executive Summary ......................................................................................................................................... - 5 - 3 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................................... - 9 - 3.1 Purpose and Scope .................................................................................................................................. - 9 - 3.2 Methodology ........................................................................................................................................... - 9 - 3.3 Literature Review .................................................................................................................................. - 10 - 4 Brisbane, Australia ......................................................................................................................................... - 12 - 4.1 Land Use Planning in Southeast Queensland ........................................................................................ - 15 - 4.2 South -

Brisbane, Australia

BRISBANE, AUSTRALIA BRIEF: SOUTH EAST BUSWAY Table of Contents BRISBANE, AUSTRALIA....................................................................1 CITY CONTEXT......................................................................................................................... 1 PLANNING AND IMPLEMENTATION BACKGROUND .................................................................. 1 SOUTH EAST BUSWAY .............................................................................................................. 2 DESIGN FEATURES ............................................................................................................... 2 STATIONS............................................................................................................................. 2 BUS OPERATIONS................................................................................................................. 3 FACILITIES MANAGEMENT................................................................................................... 3 RIDERSHIP............................................................................................................................ 3 BENEFITS ............................................................................................................................. 3 INNER NORTHERN BUSWAY ..................................................................................................... 4 ASSESSMENT ............................................................................................................................ -

South East Busway's 15Th Birthday

South East Busway’s 15th birthday Today marks the 15th birthday of one of the world’s finest busways, The South East Busway from Woolloongabba to Eight Mile Plains. State Member for Greenslopes Joe Kelly said the opening of the South East Busway was the beginning of a Brisbane busway network that had become an example of best practice for public transport around the world “Delivering more than 18,000 customers every hour to their destinations in peak periods, the 17km South East busway from Woolloongabba to Eight Mile Plains is a very popular and efficient transport choice for thousands of customers every day,” Mr Kelly said. “By comparison, buses travelling in general traffic can only carry up to 1,600 passengers an hour. “Today, there are now more than 29 kilometres of busway which includes 27 stations and 20 tunnels. More than 72 million trips are made on our busways each year. “The 17 kilometre busway runs adjacent to the South East Freeway and comprises environmentally designed busway stations and a busway operations centre that employs modern technology. “The busway stations have been developed at key suburban nodes to serve major activity centres. This allows buses to serve low-density communities, collect passengers from local roads and then join the busway for a faster trip into the city. “Owned, operated and maintained by the Department of Transport and Main Roads, the South East Busway infrastructure is an impressive operation. “More than 750 CCTV cameras monitor infrastructure, tunnels and assets 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. “The busways feature real time safety and security incident management and linear heat detectors in the tunnels can trigger water deluge system to extinguish fires. -

The Brisbane Busway Successful Public Transit Serves Australia’S Fastest Growing Region

SNAPSHOT: BRISBANE, AUSTRALIA The Brisbane Busway Successful Public Transit Serves Australia’s Fastest Growing Region Background Located in Western Australia, Brisbane is the capital city of the State of Queensland and the center of the fastest-growing region in the country. Population projections estimate that the region will grow from 2.7 million in 2006, to more than 4.2 million in 2031.1 In order to meet the transportation demands of its growing population and support a strong regional economy, Brisbane has developed an extensive bus rapid transit system. Modeled largely after the Ottawa, Canada system, the Brisbane system exemplifies the “quickway model” of BRT. The region is served by a network of dedicate busways that provide fast and convenient connection to the central business district (CBD) and major employment centers. Building on the success they’ve had to date, the region has set of goal of doubling the use of public transportation by 2031.2 Process Recognizing the Need. The city of Brisbane has long been served by an electrified commuter rail system, the “Citytrain.” The Citytrain network includes four corridors radiating out of the CBD and branching out into 7 primary corridors. While this system was historically well used, transportation planners recognized that residents located between the lines were not well served and had little access to reliable transit options linking them to employment centers. The decision to invest in the busway system is largely credited to Lord Mayor Jim Soorley, who was in office from 1991-2003. Soorley sought to transform the city of Brisbane into a globally competitive city and believed that an effective public transit system was critical to achieving this goal.