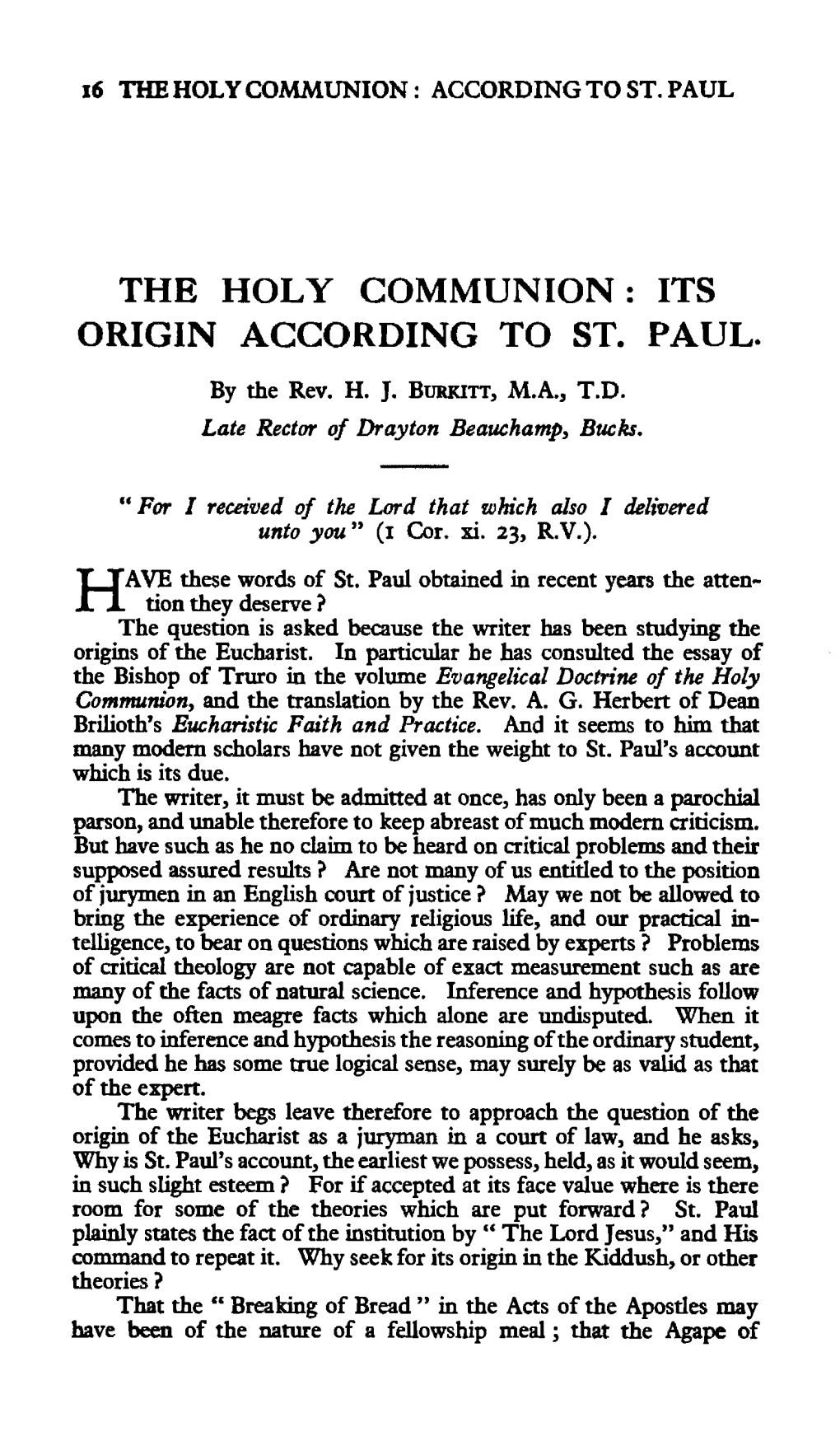

The Holy Communion : Its Origin According to St

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Catholic Doctrine of Transubstantiation Is Perhaps the Most Well Received Teaching When It Comes to the Application of Greek Philosophy

Bucknell University Bucknell Digital Commons Honors Theses Student Theses 2010 The aC tholic Doctrine of Transubstantiation: An Exposition and Defense Pat Selwood Bucknell University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/honors_theses Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Selwood, Pat, "The aC tholic Doctrine of Transubstantiation: An Exposition and Defense" (2010). Honors Theses. 11. https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/honors_theses/11 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses at Bucknell Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Bucknell Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My deepest appreciation and gratitude goes out to those people who have given their support to the completion of this thesis and my undergraduate degree on the whole. To my close friends, Carolyn, Joseph and Andrew, for their great friendship and encouragement. To my advisor Professor Paul Macdonald, for his direction, and the unyielding passion and spirit that he brings to teaching. To the Heights, for the guidance and inspiration they have brought to my faith: Crescite . And lastly, to my parents, whose love, support, and sacrifice have given me every opportunity to follow my dreams. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction………………………………..………………………………………………1 Preface: Explanation of Terms………………...………………………………………......5 Chapter One: Historical Analysis of the Doctrine…………………………………...……9 -

New Testament Revelations of Jesus of Nazareth

NEW TESTAMENT REVELATIONS OF JESUS OF NAZARETH PART I. MEDIUM: DR. DANIEL G. SAMUELS Revelation Page Dr. Daniel G. Samuels Becomes the Second Mortal Instrument to Receive Jesus' Truths. He is Told That His Present Work Will Be 1 to Receive Messages Regarding Sayings and Incidents Recorded in the New Testament, Which Will Result in a New and Corrected Gospel for Mankind. http://www.fcdt.org/store.htm 2 Revelations Dr Daniel G Samuels https://new-birth.net/samuels-messages/ https://new-birth.net/mediumship/dr-samuels-medium/ These revelations were received by Dr Samuels over the period 1954 to 1963. He was born in Brooklyn of Russian parents on 18 May 1908, and passed into spirit at 11561 Long Beach, Nassau, New York in March 1982 at the age of 73. Dr. Samuels attended Boy's High School 1922-24 and New Utrecht High School 1924-26. He was a graduate of City College (New York) in 1930. He received an M.A. from Columbia University in 1931, and a Ph.D. in Philosophy from Columbia University in 1940. His proficiency was romance languages and journalism, which he taught in both secondary schools and colleges / universities. He also worked for the US Government as a translator. He met Dr Leslie R Stone in the fall of 1954, while he was employed by the University of the District of Columbia as an instructor in Spanish. The meeting took place in a park in Washington, DC, near Dr Stone's residence. A friendship sprang up, and it was soon realized that Dr Samuels was able to take automatic writings. -

Abstract “RESPONSIVE RATHER THAN EMERGENT: INTENTIONAL

Abstract “RESPONSIVE RATHER THAN EMERGENT: INTENTIONAL EPISCOPAL LITURGY FOR THE 21ST CENTURY” NINA RANADIVE POOLEY Project under the direction of The Rt. Rev. J. Neil Alexander With the rise of emerging churches greater attention has been paid to the liturgy of The Episcopal Church; rather than attempt to be emergent, The Episcopal Church is positioned to continue its long standing tradition of liturgical adaptation to be responsive to the needs of the 21st century. An understanding of the Anglican tradition of liturgical adaptation provides Anglican principles of liturgical change and a firm foundation for crafting responsive liturgy. The paper begins with an in-depth look at the emerging church phenomenon and what the issues raised by the emergence of these communities have to teach those in mainstream liturgical traditions about the changing needs of contemporary culture. Following this introduction to emerging churches is a discussion of liturgical inculturation inherent in the development of early Christian liturgy primarily through the expertise of Anscar Chupungco and the work of the liturgical movement leading up to Sacrosanctum Concilium of Vatican II. From this look at early liturgical development the paper then considers the development of Anglican liturgy, specifically the ways in which Anglican liturgy has been adapted throughout history to meet the changing needs of the world. The purpose of this exploration is to show that not only is liturgical adaptation inherently Anglican, but also to discover the foundational Anglican principles for liturgical change. With these principles established, the paper proposes a tool or outline for clergy who wish to offer liturgy that is responsive to the world and is still in-keeping with the liturgical principles of The Episcopal Church. -

Inculturation of the Liturgy in Local Churches: Case of the Diocese of Saint Thomas, U.S

University of St. Thomas, Minnesota UST Research Online School of Divinity Master’s Theses and Projects Saint Paul Seminary School of Divinity Winter 12-2014 Inculturation of the Liturgy in Local Churches: Case of the Diocese of Saint Thomas, U.S. Virgin Islands Touchard Tignoua Goula University of St. Thomas, Minnesota, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.stthomas.edu/sod_mat Part of the History Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Tignoua Goula, Touchard, "Inculturation of the Liturgy in Local Churches: Case of the Diocese of Saint Thomas, U.S. Virgin Islands" (2014). School of Divinity Master’s Theses and Projects. 8. https://ir.stthomas.edu/sod_mat/8 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Saint Paul Seminary School of Divinity at UST Research Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in School of Divinity Master’s Theses and Projects by an authorized administrator of UST Research Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE SAINT PAUL SEMINARY SCHOOL OF DIVINITY UNIVERSITY OF ST. THOMAS Inculturation of the Liturgy in Local Churches: Case of the Diocese of Saint Thomas, U.S. Virgin Islands A THESIS Submitted to the Faculty of the School of Divinity Of the University of St. Thomas In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree Master of Arts in Theology © Copyright All Rights Reserved By Touchard Tignoua Goula St. Paul, MN 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS General Introduction..……………………………………………………………………..1 Chapter one: The Jewish Roots of Christian Liturgy……………….……………………..2 A. -

On the Holy Eucharist in the New Testament 1

E H 0 LYE t1 C H A R 1ST I N r 1-1 E! NIt W TItS T A MEN T 19 the transgressions of their wrong-doing and their sins in the of iniquity. 1 And those who enter into the covenant shall co:nre:SSlon after them saying: We have done evil, we have trans we have sinned, we and our fathers before us, in our way of . truth and justice ... his judgement upon us and upon our fathers. 3 Bauchet adds that the next column, line 9, speaks of " the com of an eternal fire." " of Belial," as in II Cor. vi, I5. added" in our way of life." added " and upon our fathers." ON THE HOLY EUCHARIST IN THE NEW TESTAMENT 1 Holy Eucharist, Christ's supreme gift of himself, fulfilment of all man's instincts of worship and sacrifice expressed in Jewish and pagan rite, is the representation by his Church under efficacious his own sacrifice on the Cross and the source of the life of his Body, cf. I Cor. xi, 26; x, 17; John vi, 51-9; Dz 938. Bond of between the members of the Body and their risen Head, it is the union between the members themselves, and the joyful pledge resurrection (cf. I Cor. x, 16f; John vi, 56; Cyr. Alex., Ady. iv, ch. v, PG lxxvi, 189-97). " That God who gave life to the world Son should not have wholly withdrawn him from the world, flesh which saved it,should still sustain it, does not that seem of his goodness? Does it not seem consistent with the very the Incarnation? It is, moreover, the only right meaning of " (Lagrange, The Gospel of Jesus Christ, I, p. -

An Overview of First Communion and Preparation

All Saints Catholic Church Catechesis of the Good Shepherd An Overview of First Communion and First Reconciliation Preparation 2016 Eucharist The Source and Summit of our Faith (Lumen Gentium, 11) The Eucharist is a mystery which perhaps none of us will fully comprehend in our lifetimes. The Church encourages the faithful to be committed to a life-long catechesis about this great Sacrament. Therefore, while we engage in immediate preparation for First Holy The Church Communion for children around encourages the 7 or 8 years of age, this faithful to be preparation for First Eucharist should not be seen as just begun committed to a or complete. The Eucharist is life-long both the summit of the child’s whole religious life since catechesis about baptism, and it is the source of this great the child’s continued growth and Sacrament. development as a child of God. Catechesis of the Good Shepherd Although CGS is 60 years old, it is more than likely that we as parents received a markedly different preparation for First Communion than our children. With this in mind, this booklet has been prepared to help explain the method and material that is utilized especially as relates to First Communion. Preparation for Holy Eucharist in the Catechesis of the Good Shepherd is both comprehensive and particular. This preparation truly begins the moment a child enters the atrium. In a prepared environment with special material for the children to explore, the experience of the atrium each week becomes a special opportunity for the child to encounter the 2 mysteries of our faith through the help of his catechist, and especially the great Catechist—the Holy Spirit. -

Temple Roots of the Liturgy

1 THE TEMPLE ROOTS OF THE LITURGY © Margaret Barker, 2000 At the centre of Christian worship is the Eucharist, yet its origins are still a matter for speculation. It used to be fashionable to seek the roots of Christian prayers and liturgy only in the synagogue or the prayers and blessings associated with communal meals. Only a generation ago, Werner could write: ‘It is remarkable how few traces of the solemn liturgies of the High Holy Days have been left in Christian worship’2, and before that, Oesterley had stated that ‘Christ was more associated with the synagogue type of worship than with that of the temple’3 The association of the Last Supper with the Passover has often led to Passover imagery being the only context considered for the context of the Eucharist. Since the New Testament interprets the death of Jesus as atonement (e.g. 1 Cor.15.3) and links the Eucharist to his death, there must have been from the start some link between Eucharist and atonement. Since Jesus is depicted as the great high priest offering his blood as the Atonement sacrifice (Heb.9.11-12), and the imagery of the Eucharist is sacrificial, this must have been the high priest’s Atonement sacrifice in the temple, rather than just the time of fasting observed by the people. The Day of Atonement It is true that very little is known about temple practices, but certain areas do invite further examination. The Letter to the Hebrews, where Christ is presented as the high priest offering the atonement sacrifice4, provides the starting point for an investigation into the temple roots of the Christian Liturgy. -

Catechesis of the Good Shepherd Summary of Presentations “Help

Catechesis of the Good Shepherd Summary of Presentations “Help Me Fall in Love with God” The philosophy of the Catechesis of the Good Shepherd program is that even very young children have a religious life. God is present to them in their deepest being and they are capable of developing both a conscious and intimate relationship with God. We provide materials based on age-appropriate Scripture passages and liturgical signs that nurture their relationship with God. The program balances exposure to our liturgy and the richness of our communal sacramental life with reading the Bible. Our program begins with presenting the New Testament to the children because it is the foundation of our faith. The youngest learn about Jesus and the beauty and wonder of the Kingdom of God through carefully chosen Bible verses that foster a deep love for Jesus. As they grow older they are encouraged to think about their personal responsibility to maintain this relationship with God and their social responsibility in the world. The oldest group studies the Old Testament in great detail and continues to deepen their understanding of the liturgy. They plan worship services and begin community service. Each presentation has specific materials designed to draw the child into the Biblical and Liturgical themes. These materials are always available to the children during their work time so they have additional opportunity to absorb the lessons. The following is a summary to the presentations offered for Level I. Classes are structured to offer a time of prayer and song, a time for the “presentation” and a time for individual work by the child. -

Encyclopedia of Religious Rites, Rituals, and Festivals RT1806 C00.Qxd 4/23/2004 2:13 PM Page Ii

RT1806_C00.qxd 4/23/2004 2:13 PM Page i encyclopedia of religious rites, rituals, and festivals RT1806_C00.qxd 4/23/2004 2:13 PM Page ii ROUTLEDGE ENCYCLOPEDIAS OF RELIGION AND SOCIETY David Levinson, Series Editor The Encyclopedia of Millennialism and Millennial Movements Richard A. Landes, Editor The Encyclopedia of African and African-American Religions Stephen D. Glazier, Editor The Encyclopedia of Fundamentalism Brenda E. Brasher, Editor The Encyclopedia of Religious Freedom Catharine Cookson, Editor The Encyclopedia of Religion and War Gabriel Palmer-Fernandez, Editor The Encyclopedia of Religious Rites, Rituals, and Festivals Frank A. Salamone, Editor RT1806_C00.qxd 4/23/2004 2:13 PM Page iii encyclopedia of religious rites, rituals, and festivals Frank A. Salamone, Editor Religion & Society A Berkshire Reference Work ROUTLEDGE New York London RT1806_C00.qxd 4/23/2004 2:13 PM Page iv Published in 2004 by Routledge 29 West 35th Street New York, NY 10001 www.routledge-ny.com Published in Great Britain by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane London EC4P 4EE www.routledge.uk.co A Berkshire Reference Work. Routledge is an imprint of Taylor & Francis Group. Copyright © 2004 by Berkshire Publishing Group Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Encyclopedia of religious rites, rituals, and festivals / Frank A. -

Jesus' Dispute in the Temple and the Origin of the Eucharist

Jesus' Dispute in the Temple and the Origin of the Eucharist Bruce Chilton CRITICAL DISCUSSION OF JESUS throughout the modern period has been stumped by a single, crucial question. Anyone who has read the Gospels knows that Jesus was a skilled teacher, a rabbi in the parlance of early Ju- daism. He composed a portrait of God as divine ruler ("the kingdom of God," in his words) and wove it together with an appeal to people to be- have as God's children (by loving both their divine father and their neighbor). At the same time it is plain that Jesus appeared to be a threat both to Jewish and to Roman authorities in Jerusalem. He would not have been crucified otherwise. The question which has nagged critical discussion concerns the relationship between Jesus the rabbi and Jesus the criminal: how does a teacher of God's ways and God's love find him- self on a cross? Scholarly pictures of Jesus which have been developed during the past two hundred years typically portray him as either an appealing, gifted teacher or as a vehement, political revolutionary. Both kinds of portrait are wanting. If Jesus' teaching was purely abstract, a matter of defining God's nature and the appropriate human response to God, it is hard to see why he would have risked his life in Jerusalem and why the local aristocracy there turned against him. On the other hand, if Jesus' purpose was to encourage some sort of terrorist rebellion against Rome, why should he have devoted so much of his ministry to telling memora- ble parables in Galilee? It is easy enough to imagine Jesus the rabbi or Jesus the revolutionary. -

The Resurrection and Early Eucharistic Liturgy

THE RESURRECTION AND EARLY EUCHARISTIC LITURGY (An investigation into thG influence of the Resurrection of Jesus Christ on the eucharistic liturgy of the early Christian Church by Vivian W. Harris, B.A. (Rhodes) Thesis submitted in part-fulfilmont of the require~ents for the degree of BACHELOR OF DIVINITY At Rhodes University, Grahrunstown South Africa. - PREFACE - The Resurrection of Jesus Christ frora the dead is absolutely central to the Christian faith, and its influ ence, in many directions, is felt throughout the Christian Church. Despite this, this Iuost important part of our faith has not received froB theologians the attention that is its due. The fact that this thesis is based upon the Resurrection is due largely to the Rev. Professor Dr. W.D. Maxwell, who guided me in this study, and I ruust record my gratitude to hiB, not only for his guidance but also for the emphasis he has placed on the Resurrection - an emphasis he has taught many others besides uyself. My thanks wust be expressed, too, to I~s. Y. II Mulders who typed and duplicated this work. Finally, a word of appreciation to the congregation I am privileged to serve, who have so patiently borne with me in this work. All quotations from the Scriptures are made fran the Revised Standard Version of the Bible, unless other wise stated. In the last section of this thesis, dealing with Three Early Liturgies, I have assumed that the reader will have a copy of these liturgies before him as he reads. V. W. H. Methodist Manse, BRAKPAN. -

A Comparative Study of Eucharistic Teachings of the Didache with Canonical, Early Christian, and Non-Christian Literature

Butler University Digital Commons @ Butler University Graduate Thesis Collection Graduate Scholarship 1-1-1960 A Comparative Study of Eucharistic Teachings of the Didache with Canonical, Early Christian, and Non-Christian Literature Joseph Richard Bennett Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/grtheses Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Catholic Studies Commons, Christianity Commons, and the History of Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Bennett, Joseph Richard, "A Comparative Study of Eucharistic Teachings of the Didache with Canonical, Early Christian, and Non-Christian Literature" (1960). Graduate Thesis Collection. 468. https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/grtheses/468 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Scholarship at Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Thesis Collection by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. (::' (This certification-sheet is to be bound with the thesis. The major pro fessor should have it fil!ed out at the oral examination.) Name of candidate: .....J.R.~~Ph .. E:J.~har.ci .. .ammf;l.tdi ..................................... Oral examination : Date ..............~.~Y. ... ~~.1 •.. f.:?.§.9. ........................................................ Committee: ...........f.r.g.f.~.f?.§.9.:r. .. f?.,., •• M?.J".iQ.Q .. i$.ro.i.t.b. ....................... , Chairman Professor Henry K. Shaw ...........°f.!:.'?.f~.~~9E .. .c!~9E!$.~ .. ~.~~~r.~............................ -~·.... ,. Thesis title: A.. C.OMP.ARATI:vE .. S.TUDY... OF.. EU.CHA.RI.STJ.C ...TEACHINGS OF 'r.HE DIDACHE WITH CANONICAL, EARLY CHRISTIAN, AND NON-CHRISTIAN LITERATURE Thesis approved in final form: Date ................ MAY, .. 1.8.,. .. l26.0 ...................................../~·· ........... .. /~) . ~· (;.{-/·' . ~- /'/, / ~· (_, J\'Ta1or Professor ............. 1......... t.l:V.: .................