Commission on Social Action of Reform Judaism Religious Action Center of Reform Judaism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

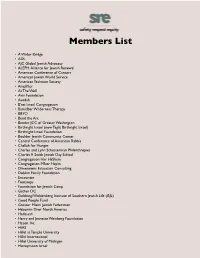

Members List Sre 2021

Members List • A Wider Bridge • ADL • AJC Global Jewish Advocacy • ALEPH: Alliance for Jewish Renewal • American Conference of Cantors • American Jewish World Service • American Technion Society • Amplifier • At The Well • Aviv Foundation • Avodah • B'nai Israel Congregation • Bamidbar Wilderness Therapy • BBYO • Bend the Arc • Bender JCC of Greater Washington • Birthright Israel (now Taglit Birthright Israel) • Birthright Israel Foundation • Boulder Jewish Community Center • Central Conference of American Rabbis • Challah for Hunger • Charles and Lynn Schusterman Philanthropies • Charles E Smith Jewish Day School • Congregation Har HaShem • Congregation M'kor Hayim • Dimensions Education Consulting • Dobkin Family Foundation • Encounter • Footsteps • Foundation for Jewish Camp • Gather DC • Goldring/Woldenberg Institute of Southern Jewish Life (ISJL) • Good People Fund • Greater Miami Jewish Federation • Habonim Dror North America • Hadassah • Harry and Jeanette Weinberg Foundation • Hazon, Inc. • HIAS • Hillel at Temple University • Hillel International • Hillel University of Michigan • Honeymoon Israel • iCenter • IKAR • Institute for Curriculum Services • International Institute for Secular Humanistic Judaism • IsraAID • Israel Institute • Israel on Campus Coalition • Israel Policy Forum • itrek • JCC Association of North America • JCFS Chicago • JDC • Jewish Community Center of Greater Pittsburgh • Jewish Community Federation and Endowment Fund • Jewish Community Foundation of Southern Arizona • Jewish Education Project • Jewish Family -

Amudim Community Resources, INC. Amount

Beis Community 2018 Amount: $7,000 Project: Women’s Leadership Development Amudim Community Resources, INC. • Supports women’s leadership development for Amount: $10,000 volunteers of an intentional and inclusive Project: Project Shmirah Orthodox Jewish community in Washington • Hold age-appropriate workshops in yeshivas Heights that attracts those traditionally on the and day schools to teach children about margins. healthy boundaries and strategies to increase emotional wellbeing. They will also provide Moving Traditions events in community centers, synagogues, and Amount: $60,000 homes that will encourage adults to become Project: National Jewish Summer Camp Healthy community advocates against abuse. Sexuality Initiative Center for Initiatives in Jewish Education (CIJE) • Moving Traditions will prepare two cohorts of Amount: $10,000 camp directors and assistant directors to train Project: YES I CAN their staff on bias prevention, harassment, and • Motivate, encourage, and support girls to peer pressure among staff and campers. pursue STEM education and careers through exposure to mentors and educational, T’ruah volunteer, and internship opportunities. Amount: $75,000 Additionally, CIJE will establish the YES I CAN Project: Development of Rabbinic Network career center which will establish STEM • Supports strengthening their rabbinic network internships and opportunities in the US and and training rabbis and cantors to be more Israel and offer assistance to young women effective leaders and to amplify the moral with college and scholarship applications. voice of the Jewish community. T’ruah will Jews for Racial and Economic Justice (JFREJ) develop trainings on anti-Semitism and Amount: $75,000 provide support to their network, particularly Project: Leadership Development women clergy, and promote the voices of • JWFNY’s unrestricted funds will support women as experts in teaching positions and leadership development and political journalism. -

The Ingeborg, Tamara & Yonina Rennert Women in Judaism Forum Jewish Women Changing America: Cross Generational-Conversations

THE INGEBORG, TAMARA & YONINA RENNERT WOMEN IN JUDAISM FORUM JEWISH WOMEN CHANGING AMERICA: CROSS GENERATIONAL-CONVERSATIONS SUNDAY, 30 OCTOBER 2005 PANEL DISCUSSION 3: “CHANGING JUDAISM” Janet Jakobsen: This first panel this afternoon is going to look at changing Judaism. Actually, it was the first question raised during last night’s panel: How do we think about changing Jewish practice? How do we think about changing Jewish religious communities? So it’s obviously a topic that’s on a number of people’s minds, and we’ve been able to bring together a really great panel to discuss that with you. As always, the moderator will set the context for us, and then the panelists will speak with each other. And then we’ll get a chance to hear from all of you. I look forward to another really interesting conversation. We have with us today a particularly impressive moderator in Judith Plaskow, who, again, many of you already know. She is a professor of religious studies at Manhattan College and a Jewish feminist theologian. She has been teaching, writing and speaking about feminist studies in religion and Jewish feminism for over 30 years. She’s been a leader at the American Academy of Religion, and was, in fact, the president of the American Academy of Religion. With Carol Christ, she co-edited Womanspirit Rising: A Feminist Reader in Religion, and she edited Weaving The Visions: New Patterns in Feminist Spirituality, both anthologies of feminist theology used in many religious studies courses, as well as women’s studies courses. With Elizabeth Schüssler Fiorenza, she co-founded The Journal of Feminist Studies and Religion, which is a very important journal in religious studies. -

Congregation Beth Ahabah Re-Imagining Reform Judaism

CONGREGATION BETH AHABAH b’yachad VOLUME 78 NO. 04 FEBRUARY/MARCH 2013 | Sh’VAT/ADAR 1/NISAN 5773 bethahabah.org RE-IMAGINING REFORM JUDAISM THROUGH COMMUNITY by Linda Ferguson Dinner was provided by Six Points Sports Academy, a URJ summer sports On November 9, 2012, seven of your camp, at the American Hebrew Acadmy fellow congregants and friends as well in Greensboro. After dinner we were as Rabbis Beifield and Gallop headed for Greensboro, North Carolina for a Regional Shabbatone. Sponsored by Temple Emanuel and the idea and planing of its Rabbi Fred Gutman, we words, the need to strengthen Reform were involved in prayer, education, Judaism through community. music and, of course....food. Saturday morning we had Shabbat Our group was joined by about Services at Temple Emanuel and Rabbi 70 members of Temple Emanuel entertained by the wonderul music of Gutman led us in prayer and music. and about the same number from the Josh Nelson Project. He also talked about the need for congregations around the Mid Atlantic community and belonging. The choir and Region. We began the Shabbatone with The 24+ hours provided us with a two cantorial solists provided beautiful a delicious Shabbat dinner at Temple wonderful oportunity to pray, talk and music Friday night and Saturday Emanuel on Friday evening, followed by build community with members of morning. Our luncheon speaker was services that included an outstanding our sister congregations around our Rabbi David Saperstein Director and area. It is the start of our embracing Counsel of the Religious Action Center, the opportunity to reach out and one of the most significant religious bring in new friends and enhance our lobby groups in the country. -

June 8, 2019 Shavuot Across Brooklyn

JUNE 8, 2019 SHAVUOT ACROSS BROOKLYN ALL-NIGHT CELEBRATION SPONSORED BY: Altshul, Base BKLYN, Beloved, Brooklyn Beit Midrash, Brooklyn Jews, Congregation Beth Elohim, Idra: House of Coffee/Culture/Learning, Hannah Senesh Community Day School, Kane Street Synagogue, Kavod: A Brooklyn Partnership Minyan, Kolot Chayeinu/Voices of Our Lives, Mishkan Minyan, Park Slope Jewish Center, Prospect Heights Shul, Repair the World NYC, Romemu Brooklyn, Shir HaMaalot, UJA-Federation of New York, and Union Temple of Brooklyn #ShavuotAcrossBrooklyn cbebk.org @cbebk /cbebk Schedule at a Glance 8:00 PM Keynote Session with author Nathan Englander (Sanctuary) Doors open at 7:30pm 9:15 PM Services: Clergy-led Contemporary Musical Service (Sanctuary) Traditional/Egalitarian Service (Rotunda) Orthodox Service (Chapel) 10:00 PM Cheesecake in the Social Hall 10:30 PM Onward Learning throughout the building Each session is 60 minutes, followed by a 5 minute break **asterisks are next to sessions that use instruments, electricity, or writing 10:30 PM Learning Block 1 ● History and Mystery of Tikkun Leil Shavuot with Basya Schechter (Brosh)** ● Psalm Study Marathon with Barat Ellman (Rimon) ● Halakha’s Attitude Toward Transgender and Transsexual Inclusion with Ysoscher Katz (Study) ● Love Like a Tree with Sara Luria (Erez) ● The Torah of Pleasure, Joy, and the Erotic with Rachel Timoner (Chapel) ● First Impressions: What the beginning of our sacred texts teaches us with Josh Weinberg (Shaked) ● Amos and Moral Torah with David Kline (Limon) ● The Torah Before The -

Beth David Synagogue • Chabad of Oneonta •

July 17-30, 2020 Published by the Jewish Federation of Greater Binghamton Volume XLVIX Number 28 BINGHAMTON, NEW YORK Area Synagogues: Beth David Synagogue • Chabad of Oneonta • Con- gregation Tikkun v'Or, Ithaca Reform Temple • Kol Haverim: Fin- gerlakes Community for Humanistic Judaism • Norwich Jewish Center • Penn-York Jewish Community • Rohr Chabad Center of Binghamton • Roitman Chabad Center at Cornell • Temple Beth-El, Ithaca • Temple Beth El, Oneonta • Temple Brith Sholom, Cortland • Temple Concord • Temple Israel • Binghamton Hadassah • Board of Rabbis • B'Yachad Ithaca Jewish Preschool • College of Jewish Studies • Community Relations Committee • Hillel Academy • In- ternational Jewish Film Fest of Greater Binghamton • Ithaca Area United Jewish Community • Jewish Community Center • Jewish Family Service • Jewish Federation of Greater Binghamton • The Reporter Group • William H. Seigel Lodge of B'nai B'rith • Uni- versities: Binghamton University Zionist2020 Organization • Center for Israel Studies at Binghamton University • Center for Jewish Living, Cornell University • Cornell University Hillel – Yudow- itz Center for Jewish Life • Hillel at Binghamton • Hillel at Ithaca College • Hillel at SUNY College of Oneonta • Jewish Studies Program at Cornell University • Judaic Studies Depart- ment, Binghamton University • MEOR Upstate • SUNY Cortland Hillel Area Synagogues: Beth David Synagogue • Chabad of Oneonta • Congregation Tikkun v'Or, Ithaca Reform Temple • Kol Haverim: Fingerlakes Community for Hu- manistic Judaism • Norwich -

Book of the Occurrences of the Times to Jeshurun in the Land of Israel - Koṛ Ot Ha-ʻitim Li-Yeshurun Be-ʾerets Yisŕ Aʾel

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Miscellaneous Papers Miscellaneous Papers 8-2011 Book of the Occurrences of the Times to Jeshurun in the Land of Israel - Koṛ ot ha-ʻitim li-Yeshurun be-ʾErets Yisŕ aʾel David G. Cook Sol P. Cohen Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/miscellaneous_papers Part of the Islamic World and Near East History Commons, Jewish Studies Commons, and the Religion Commons Cook, David G. and Cohen, Sol P., "Book of the Occurrences of the Times to Jeshurun in the Land of Israel - Koṛ ot ha-ʻitim li-Yeshurun be-ʾErets Yisŕ aʾel" (2011). Miscellaneous Papers. 10. https://repository.upenn.edu/miscellaneous_papers/10 This is an English translation of Sefer Korot Ha-'Itim (First Edition, 1839; Reprint with Critical Introduction, 1975) This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/miscellaneous_papers/10 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Book of the Occurrences of the Times to Jeshurun in the Land of Israel - Koṛ ot ha-ʻitim li-Yeshurun be-ʾErets Yisŕ aʾel Abstract This work was authored by Menahem Mendel me-Kaminitz (an ancestor of one of the current translators David Cook) following his first attempt ot settle in the Land of Israel in 1834. Keywords Land of Israel, Ottoman Palestine, Menahem Mendel me-Kaminitz, Korat ha-'itim, history memoirs Disciplines Islamic World and Near East History | Jewish Studies | Religion Comments This is an English translation of Sefer Korot Ha-'Itim (First Edition, 1839; Reprint with Critical Introduction, 1975) This other is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/miscellaneous_papers/10 The Book of the Occurrences of the Times to Jeshurun in the Land of Israel Sefer KOROT HA-‘ITIM li-Yeshurun be-Eretz Yisra’el by Menahem Mendel ben Aharon of Kamenitz Translation by: David G. -

March 2020 | Adar/Nissan 5780 | Vol

March 2020 | Adar/Nissan 5780 | Vol. 46 No. 6 FEEL THE LOVE AT ANNUAL CELEBRATIONS PAGE 9 PRE-PASSOVER ON THE GO A STEP BACK PAMPERING WITH PP 10-11 EVERYWHERE WITH IN TIME WITH ALLY RASKIN 6 TEEN EMANU-EL 10 CANTOR MENDELSON 19 March2020.indd 1 2/17/20 11:50 AM CLERGY MESSAGE The Mourner’s Kaddish avid Stern i D bb a R itgadal v’yitkadash shmei rabba: What’s the same—we end up standing and reciting the eleven syllables that begin a Kaddish together as a community with all of the beauty and symphony. The Mourner’s power of that familiar Reform practice. What’s different— Kaddish is music after all we provide an invitation for mourners to rise so they can Y—not a melody written in notes or be recognized by others, so we can continue to deepen our scales, but a prayer whose primary practice as a congregation of caring and support for people impact on us emerges from its sound both within our walls and beyond them. (Please note: and rhythm more than the manifest mourners will not be invited to rise by name and no mourner content of its words. will be required to stand separately if they do not wish to; this Of course, the ancient Aramaic words still matter, opportunity is strictly voluntary.) surprising as they are: a prayer that we recite in mourning, yet We will begin this experiment in practice in April in Friday which does not mention death. A prayer that tradition calls night Shabbat services in Stern Chapel and Saturday morning upon us to offer when we might feel most deserted by God, Shabbat services in Lef kowitz Chapel, and we will be interested and yet a prayer which piles superlative upon superlative in in your feedback. -

Represented Organizations

Represented Organizations Abraham Initiatives Foundation for Jewish Camp AC & JC Foundation GatherDC ALEPH: Alliance for Jewish Renewal Gender Equity in Hiring Project American Jewish World Service (AJWS) Goldring/Woldenberg Institute of Southern Jewish Life (ISJL) American Technion Society Good People Fund At The Well Habonim Dror North America Atlanta Jews of Color Council Hazon Aviv Foundation Hillel at Drexel University Avodah Hillel International BBYO Hillel Ontario Birthright Israel Foundation Honeycomb B'nai B'rith Camp Honeymoon Israel CFAR Hornstein Program in Jewish Professional Leadership Charles and Lynn Schusterman Family Philanthropies Human Resources Compliance and Dispute Resolution Services Combined Jewish Philanthropies of Greater Boston iCenter Congregation Beth Elohim IKAR Congregation Har HaShem Institute for Jewish Spirituality CORIPHERY Holistic Consulting Services IsraAID - The Israeli Forum for International Humanitarian Aid Dayenu: A Jewish Call to Climate Action Israel On Campus Coalition Dobkin Family Foundation Israel Policy Forum Footsteps itrek Represented Organizations JCC Association of North America Jewish Women International JCC Chicago Jewish Women's Archive JDC Jewish Women’s Foundation JDC Entwine Jewish Women's Foundation of Greater Pittsburgh Jewish Community Foundation of Los Angeles Jewish Women’s Foundation of Metropolitan Chicago Jewish Community Relations Council Jewish Women's Foundation of New York Jewish Council for Public Affairs Jewish Women's Foundation of Pittsburgh Jewish Education -

Jewish Perspectives on Sexuality

The Sacred Encounter: Jewish Perspectives on Sexuality Edited by Rabbi Lisa J. Grushcow, DPhil Study Guide by Liz Piper-Goldberg CCAR Press http://www.ccarpress.org The Sacred Encounter: Jewish Perspectives on Sexuality Study Guide Section One: Study Tracks Track Title Notes 1 Marriage Intended for those offering premarital counseling, married couples, marriage counselors, or an adult education course on Judaism and marriage 2 LGBTQ Inclusion Intended for a welcoming/inclusion committee to study together, or for an adult education course on LGBTQ inclusion in a Jewish communal setting 3 Reform Jewish Intended for a confirmation or post-confirmation class,* Reform Perspectives Jewish professionals, Reform Jewish lay leaders, or an adult education course on Reform perspectives on sexuality 4 Social Justice and Intended for a social action committee to study together, or for Human Rights an adult education course on social justice/human rights within the realm of sex and sexuality 5 Sexual Ethics and Intended for an adult education course on how Jewish traditions Values and beliefs can influenced sexual ethics, values, and behaviors 6 WRJ/Sisterhood Intended for a Sisterhood or Women of Reform Judaism (WRJ) group discussion series and/or book club 7 MRJ/Brotherhood Intended for a Brotherhood or Men of Reform Judaism (MRJ) group discussion series and/or book club 8 Teen Learning Intended for teens and those who work with them* CCAR Press 2 The Sacred Encounter: Jewish Perspectives on Sexuality Study Guide Each track lists several subtopics that are covered in one or more chapters of The Sacred Encounter. You can opt to study just one chapter from each subtopic, dive into a particular subtopic and cover every chapter, or use some combination of the subtopics and chapters covered in each track for a longer period of study. -

Gender Equity and Leadership Initiative

Gender Equity and Leadership Initiative A Research and Planning Task Force of the Leadership Commons Task Force Leadership Team: Dr. Shira D. Epstein, JTS Faculty, Chair Dr. Andrea Jacobs, Project Director Contributions and general support by: Dr. Bill Robinson Debbie Singfer Mark S. Young SPRING 2019 GENDER EQUITY AND LEADERSHIP INITIATIVE | The William Davidson Graduate School of Jewish Education | Spring 2019 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY November 2018 In 2017, the Leadership Commons of the William Davidson Graduate School of Jewish Education of JTS launched the Gender Equity and Leadership Initiative (initially the Women in Jewish Leadership Initiative) to explore ways in which we might explore and better understand the landscape of gender equity and Jewish educational leadership. The initiative task force used a two-pronged approach: Dr. Shira D. Epstein led an internal process exploring ways that JTS could continue to enhance gender equity and leadership within the institution through teaching and learning, and Dr. Andrea Jacobs, an outside consultant, led a process to explore the needs of professionals in the field of Jewish education. Over the course of the planning and research phase, Dr. Jacobs and Dr. Epstein facilitated and designed activities and approaches to gather information that would help shape a series of findings and suggestions, included in this report. While this report is primarily focused on the field-facing process of the initiative, we will also reference some learnings of the internal process. The primary activities of the initiative’s field-facing researching and planning phase included: • Recruitment and convening of an advisory committee of Jewish leaders representing a broad spectrum of the Jewish educational landscape and others with relevant experience (See a listing of Advisory Committee members in Appendix A). -

Sisterhood and the Modern Woman

SISTERHOOD AND THE MODERN WOMAN Transforming Women’s Programming In the Reform Temple Case Study: Temple Emanuel of Tempe Submitted as partial requirement for Fellow of Temple Administration degree National Association of Temple Administrators Nanci B. Wilharber Temple Emanuel of Tempe Tempe Arizona November 8, 2005 1 SISTERHOOD AND THE MODERN WOMAN Transforming Women’s Programming in the Reform Temple Case Study: Temple Emanuel of Tempe Then drew near the daughters of Zelophehad: Mahlah, Noah, Hoglah, Milcah, and Tirzah. And they stood before Moses, and before Eleazar the priest, and before the princes and all the congregation, at the door of the tent of meeting, saying: “Our father died in the wilderness, and he was not among the company of them that gathered themselves together against Adonai in the company of Korah, but he died in his own sin; and he had no sons. Why should the name of our father be done away from among his family, because he had no son? Give unto us a possession among the brethren of our father.” And Adonai spoke unto Moses saying, “The daughter of Zelophehad speak right; thou shalt surely give them a possession of an inheritance among their father’s brethren; and thou shalt cause the inheritance of their father to pass unto them.”1 Sisterhood: the thought conjures up images of bespectacled, gray-haired bubbies in the Temple kitchen baking rugelach & brewing coffee for an Oneg Shabbat; stocking the shelves of the Gift Shop for the annual Chanukah sale; preparing charoset for the congregational Passover Seder; advocating for the rights of women and children, just like the daughters of Zelophehad in the Torah.