Book of the Occurrences of the Times to Jeshurun in the Land of Israel - Koṛ Ot Ha-ʻitim Li-Yeshurun Be-ʾerets Yisŕ Aʾel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Israel Teaching Letter

BRIDGES FOR PEACE Israel Teaching Letter Vol. # 770410 April 2010 Bridges for Peace Your Israel Connection ® n International Headquarters P.O. Box 1093 Jerusalem, Israel Tel: (972) 2-624-5004 [email protected] n Australia P.O. Box 1785, Buderim Queensland 4556 Tel: 07-5453-7988 [email protected] n Canada P.O. Box 21001, RPO Charleswood Winnipeg, MB R3R 3R2 Tel: 204-489-3697, [email protected] n Japan Taihei Sakura Bldg. 5F 4-13-2 Taihei, Sumida-Ku Tokyo 130 0012 Tel: 03-5637-5333, [email protected] n New Zealand P.O. Box 10142 Te Mai, Whangarei Tel: 09-434-6527 [email protected] n South Africa P.O. Box 1848 Durbanville 7551 Tel: 021-975-1941 [email protected] n United Kingdom 11 Bethania Street, Maesteg Bridgend, Wales CF34 9DJ Tel: 01656-739494 [email protected] n United States P.O. Box 410037 Melbourne, FL 32941-0037 Tel: 800-566-1998 Product orders: 888-669-8800 [email protected] www.bridgesforpeace.com 1 GUARD YOUR TONGUE “STICKS AND STONES MAY BREAK YOUR BONES, but words will never hurt you.” Have you ever heard this seemingly innocent childhood taunt? Perhaps you’ve even used it yourself in response to some unkind phrase or words. Most of us, at some point in our lives, have both said something bad about another per- son and have had another person say something bad about us. We tend to think that what we said really didn’t hurt the other person, but we also tend to long remember the hurt that another person’s words have caused us. -

Moses Hayim Luzzatto's Quest for Providence

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 10-2014 'Like Iron to a Magnet': Moses Hayim Luzzatto's Quest for Providence David Sclar Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/380 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] “Like Iron to a Magnet”: Moses Hayim Luzzatto’s Quest for Providence By David Sclar A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in History in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The City University of New York 2014 © 2014 David Sclar All Rights Reserved This Manuscript has been read and accepted by the Graduate Faculty in History in satisfaction of the Dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Prof. Jane S. Gerber _______________ ____________________________________ Date Chair of the Examining Committee Prof. Helena Rosenblatt _______________ ____________________________________ Date Executive Officer Prof. Francesca Bregoli _______________________________________ Prof. Elisheva Carlebach ________________________________________ Prof. Robert Seltzer ________________________________________ Prof. David Sorkin ________________________________________ Supervisory Committee iii Abstract “Like Iron to a Magnet”: Moses Hayim Luzzatto’s Quest for Providence by David Sclar Advisor: Prof. Jane S. Gerber This dissertation is a biographical study of Moses Hayim Luzzatto (1707–1746 or 1747). It presents the social and religious context in which Luzzatto was variously celebrated as the leader of a kabbalistic-messianic confraternity in Padua, condemned as a deviant threat by rabbis in Venice and central and eastern Europe, and accepted by the Portuguese Jewish community after relocating to Amsterdam. -

SHABBETAI TZVI the Biggest Hoax in Jewish History Nathan the Prophet and Tzvi the Messiah

1 SHABBETAI TZVI The Biggest Hoax in Jewish History While faith in the coming of the messiah is a linchpin of Judaism, Jews have traditionally taken a patient, quiet approach to their messianic beliefs. Since the devastation wreaked by false messiah Bar Kochba and his rebellion against the Romans, and the centuries of persecution caused by another messianic movement — Christianity — Jews have been understandably suspicious about anyone’s claim to be God’s anointed. The rabbis of the Talmud went so far as to introduce specific prohibitions against messianic agitation, instituting the “three oaths” which prohibited any attempt to “force the end” by bringing the messiah before his allotted time (Babylonian Talmud. Yet in the mid-17th century, belief in the false messiah Shabbetai Tzvi spread like wildfire throughout the Jewish world, sweeping up entire communities and creating a crisis of faith unprecedented in Jewish history. Shabbetai Tzvi was said to be born on the 9th of Av in 1626, to a wealthy family of merchants in Smyrna (now Izmir, Turkey). He received a thorough Talmudic education and, still in his teens, was ordained as a hakham — a member of the rabbinic elite. However, Shabbetai Tzvi was interested less in Talmud than in Jewish mysticism. Starting in his late teens he studied kabbalah, attracting a group of followers whom he initiated into the secrets of the mystical tradition. Shabbetai Tzvi battled with what might now be diagnosed as severe bipolar disorder. He understood his condition in religious terms, experiencing his manic phases as moments of “illumination” and his times of depression as periods of “fall,” when God’s face was hidden from him. -

Some Highlights of the Mossad Harav Kook Sale of 2017

Some Highlights of the Mossad HaRav Kook Sale of 2017 Some Highlights of the Mossad HaRav Kook Sale of 2017 By Eliezer Brodt For over thirty years, starting on Isru Chag of Pesach, Mossad HaRav Kook publishing house has made a big sale on all of their publications, dropping prices considerably (some books are marked as low as 65% off). Each year they print around twenty new titles. They also reprint some of their older, out of print titles. Some years important works are printed; others not as much. This year they have printed some valuable works, as they did last year. See here and here for a review of previous year’s titles. If you’re interested in a PDF of their complete catalog, email me at [email protected] As in previous years, I am offering a service, for a small fee, to help one purchase seforim from this sale. The sale’s last day is Tuesday. For more information about this, email me at Eliezerbrodt-at-gmail.com. Part of the proceeds will be going to support the efforts of the Seforim Blog. What follows is a list and brief description of some of their newest titles. 1. הלכות פסוקות השלם,ב’ כרכים, על פי כת”י ששון עם מקבילות מקורות הערות ושינויי נוסחאות, מהדיר: יהונתן עץ חיים. This is a critical edition of this Geonic work. A few years back, the editor, Yonason Etz Chaim put out a volume of the Geniza fragments of this work (also printed by Mossad HaRav Kook). 2. ביאור הגר”א ,לנ”ך שיר השירים, ב, ע”י רבי דוד כהן ור’ משה רביץ This is the long-awaited volume two of the Gr”a on Shir Hashirim, heavily annotated by R’ Dovid Cohen. -

1 Kings 11:14-40 “Solomon's Adversaries”

1 Kings 11:14-40 “Solomon’s Adversaries” 1 Kings 11:9–10 9 So the LORD became angry with Solomon, because his heart had turned from the LORD God of Israel, who had appeared to him twice, 10 and had commanded him concerning this thing, that he should not go after other gods; but he did not keep what the LORD had commanded. Where were the Prophets David had? • To warn Solomon of his descent into paganism. • To warn Solomon of how he was breaking the heart of the Lord. o Do you have friends that care enough about you to tell you when you are backsliding against the Lord? o No one in the Electronic church to challenge you, to pray for you, to care for you. All of these pagan women he married (for political reasons?) were of no benefit. • Nations surrounding Israel still hated Solomon • Atheism, Agnostics, Gnostics, Paganism, and Legalisms are never satisfied until you are dead – and then it turns to kill your children and grandchildren. Exodus 20:4–6 4 “You shall not make for yourself a carved image—any likeness of anything that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth; 5 you shall not bow down to them nor serve them. For I, the LORD your God, am a jealous God, visiting the iniquity of the fathers upon the children to the third and fourth generations of those who hate Me, 6 but showing mercy to thousands, to those who love Me and keep My commandments. -

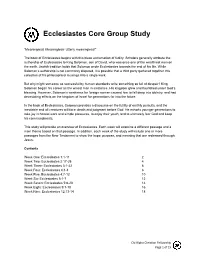

Ecclesiastes Core Group Study

Ecclesiastes Core Group Study “Meaningless! Meaningless! Utterly meaningless!” The book of Ecclesiastes begins with this bleak exclamation of futility. Scholars generally attribute the authorship of Ecclesiastes to King Solomon, son of David, who was once one of the wealthiest men on the earth. Jewish tradition holds that Solomon wrote Ecclesiastes towards the end of his life. While Solomon’s authorship is not commonly disputed, it is possible that a third party gathered together this collection of his philosophical musings into a single work. But why might someone so successful by human standards write something so full of despair? King Solomon began his career as the wisest man in existence. His kingdom grew and flourished under God’s blessing. However, Solomon’s weakness for foreign women caused him to fall deep into idolatry, and had devastating effects on the kingdom of Israel for generations far into the future. In the book of Ecclesiastes, Solomon provides a discourse on the futility of earthly pursuits, and the inevitable end all creatures will face: death and judgment before God. He exhorts younger generations to take joy in honest work and simple pleasures, to enjoy their youth, and to ultimately fear God and keep his commandments. This study will provide an overview of Ecclesiastes. Each week will examine a different passage and a main theme based on that passage. In addition, each week of the study will include one or more passages from the New Testament to show the hope, purpose, and meaning that are redeemed through Jesus. Contents Week One: Ecclesiastes 1:1-11 2 Week Two: Ecclesiastes 2:17-26 4 Week Three: Ecclesiastes 3:1-22 6 Week Four: Ecclesiastes 4:1-3 8 Week Five: Ecclesiastes 4:7-12 10 Week Six: Ecclesiastes 5:1-7 12 Week Seven: Ecclesiastes 5:8-20 14 Week Eight: Ecclesiastes 9:1-10 16 Week Nine: Ecclesiastes 12:13-14 18 Chi Alpha Christian Fellowship Page 1 of 19 Week One: Ecclesiastes 1:1-11 Worship Idea: Open in prayer, then sing some worship songs Opening Questions: 1. -

John Hagee, Christian Zionism, Us Foreign Policy and the State of Israel

JOHN HAGEE, CHRISTIAN ZIONISM, U.S. FOREIGN POLICY AND THE STATE OF ISRAEL: AN INTERTWINED RELATIONSHIP Master’s Thesis Presented to the Near Eastern and Judaic Studies department Brandeis University S. Ilan Troen, Advisor In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts By Michael Kupferberg May 2009 Copyright by Michael Kupferberg May, 2009 ABSTRACT John Hagee, Christian Zionism, U.S. Foreign Policy and the State of Israel: An Intertwined Relationship A thesis presented to the Near Eastern and Judaic Studies department Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Waltham, MA By Michael Kupferberg Christian Zionism while originating in England over two centuries ago is currently experiencing a reinvigoration, especially in the political world. Christian Zionists are using politics as a way to fulfill Biblical prophecy, by influencing powerful politicians in all levels of government to support Israel. The most vocal, and prominent leader within the Christian Zionist movement is Pastor John Hagee. Through the establishment of his organization Christians United for Israel, Hagee has localized and given a tangible center for Christian Zionist activists. Additionally, the movement has gained membership as it was established in the model of a grassroots organization. Hagee has become a well known figure in the political community, and garners national media attention. While it has become fashionable in recent times to criticize Jewish organizations such as AIPAC, it is the Christian Zionist organizations which yield a large portion of power in Washington. However, it is crucial to realize that while CUFI and groups like it may yield some power in Washington, and account for some of the decision making that goes into U.S. -

Ecclesiastes “Life Under the Sun”

Ecclesiastes “Life Under the Sun” I. Introduction to Ecclesiastes A. Ecclesiastes is the 21st book of the Old Testament. It contains 12 chapters, 222 verses, and 5,584 words. B. Ecclesiastes gets its title from the opening verse where the author calls himself ‘the Preacher”. 1. The Septuagint (the translation of the Hebrew into the common language of the day, Greek) translated this word, Preacher, as Ecclesiastes and thus e titled the book. a. Ecclesiastes means Preacher; the Hebrew word “Koheleth” carries the menaing of preacher, teacher, or debater. b. The idea is that the message of Ecclesiastes is to be heralded throughout the world today. C. Ecclesiastes was written by Solomon. 1. Jewish tradition states Solomon wrote three books of the Bible: a. Song of Solomon, in his youth b. Proverbs, in his middle age years c. Ecclesiastes, when he was old 2. Solomon’s authorship had been accepted as authentic, until, in the past few hundred years, the “higher critics” have attempted to place the book much later and attribute it to someone pretending to be Solomon. a. Their reasoning has to do with a few words they believe to be of a much later usage than Solomon’s time. b. The internal evidence, however, strongly supports Solomon as the author. i. Ecc. 1:1 He calls himself the son of David and King of Jerusalem ii. Ecc. 1:12 Claims to be King over Israel in Jerusalem” iii. Only Solomon ruled over all Israel from Jerusalem; after his reign, civil war split the nation. Those in Jerusalem ruled over Judah. -

The History of World Civilization. 3 Cyclus (1450-2070) New Time ("New Antiquity"), Capitalism ("New Slaveownership"), Upper Mental (Causal) Plan

The history of world civilization. 3 cyclus (1450-2070) New time ("new antiquity"), capitalism ("new slaveownership"), upper mental (causal) plan. 19. 1450-1700 -"neoarchaics". 20. 1700-1790 -"neoclassics". 21. 1790-1830 -"romanticism". 22. 1830-1870 – «liberalism». Modern time (lower intuitive plan) 23. 1870-1910 – «imperialism». 24. 1910-1950 – «militarism». 25.1950-1990 – «social-imperialism». 26.1990-2030 – «neoliberalism». 27. 2030-2070 – «neoromanticism». New history. We understand the new history generally in the same way as the representatives of Marxist history. It is a history of establishment of new social-economic formation – capitalism, which, in difference to the previous formations, uses the economic impelling and the big machine production. The most important classes are bourgeoisie and hired workers, in the last time the number of the employees in the sphere of service increases. The peasants decrease in number, the movement of peasants into towns takes place; the remaining peasants become the independent farmers, who are involved into the ware and money economy. In the political sphere it is an epoch of establishment of the republican system, which is profitable first of all for the bourgeoisie, with the time the political rights and liberties are extended for all the population. In the spiritual plan it is an epoch of the upper mental, or causal (later lower intuitive) plan, the humans discover the laws of development of the world and man, the traditional explanations of religion already do not suffice. The time of the swift development of technique (Satan was loosed out of his prison, according to Revelation 20.7), which causes finally the global ecological problems. -

Lelov: Cultural Memory and a Jewish Town in Poland. Investigating the Identity and History of an Ultra - Orthodox Society

Lelov: cultural memory and a Jewish town in Poland. Investigating the identity and history of an ultra - orthodox society. Item Type Thesis Authors Morawska, Lucja Rights <a rel="license" href="http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/3.0/"><img alt="Creative Commons License" style="border-width:0" src="http://i.creativecommons.org/l/by- nc-nd/3.0/88x31.png" /></a><br />The University of Bradford theses are licenced under a <a rel="license" href="http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/">Creative Commons Licence</a>. Download date 03/10/2021 19:09:39 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10454/7827 University of Bradford eThesis This thesis is hosted in Bradford Scholars – The University of Bradford Open Access repository. Visit the repository for full metadata or to contact the repository team © University of Bradford. This work is licenced for reuse under a Creative Commons Licence. Lelov: cultural memory and a Jewish town in Poland. Investigating the identity and history of an ultra - orthodox society. Lucja MORAWSKA Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Social and International Studies University of Bradford 2012 i Lucja Morawska Lelov: cultural memory and a Jewish town in Poland. Investigating the identity and history of an ultra - orthodox society. Key words: Chasidism, Jewish History in Eastern Europe, Biederman family, Chasidic pilgrimage, Poland, Lelov Abstract. Lelov, an otherwise quiet village about fifty miles south of Cracow (Poland), is where Rebbe Dovid (David) Biederman founder of the Lelov ultra-orthodox (Chasidic) Jewish group, - is buried. -

Jewish Judicial Autonomy in Nineteenth Century Jerusalem: Background, Jurisdiction, Structure

14 JEWISH JUDICIAL AUTONOMY IN NINETEENTH CENTURY JERUSALEM: BACKGROUND, JURISDICTION, STRUCTURE by ELIMELECH WESTREICH∗ 1. Introduction This study focuses on Jewish judicial autonomy in Jerusalem at the end of the Ottoman period, mainly the Sephardic court that was the official rabbinical court recognized by law. I will introduce the Islamic background of Jewish autonomy, including its relations with the Sharia courts, the new geo-political environment in which the official Sephardic court operated and the institutional framework within which it was located, the scope of its jurisdiction and the structure of the court. The Sephardic rabbinical court was part of the official rabbinical institution, which was part of the Jewish community organization. At the head of the organization was the Chief Rabbi, whose Jewish title was Rishon Lezion (“The First in Zion”) and whose official Ottoman title was -akham Bashi. This organization had close ties to the political and cultural order of the Ottoman Empire and fulfilled an important duty in those days. However, the disintegration of the Ottoman Empire at the end of WWI also spelled the end of the Jewish institutional organization. Nevertheless, the Sephardic rabbinical court of the Ottoman era served as a source of inspiration for the development of the Jewish judicial system in the period of the British Mandate, both with respect to the extent of judicial authority and with respect to the close connection between the rabbinical court and the institution of the rabbinate. These components of the Sephardic rabbinical court remain present, in principle, in the State of Israel to this day. The Sephardic rabbinical court in Jerusalem was created and operated at a multidimensional historical junction. -

Shells and Ochre in Middle Paleolithic Qafzeh Cave, Israel: Indications for Modern Behavior

Journal of Human Evolution 56 (2009) 307–314 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Human Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jhevol Shells and ochre in Middle Paleolithic Qafzeh Cave, Israel: indications for modern behavior Daniella E. Bar-Yosef Mayer a,*, Bernard Vandermeersch b, Ofer Bar-Yosef c a The Leon Recanati Institute for Maritime Studies and Department of Maritime Civilizations, University of Haifa, Haifa 31905, Israel b Laboratoire d’Anthropologie des Populations du Passe´, Universite´ Bordeaux 1, Bordeaux, France c Department of Anthropology, Harvard University, Cambridge MA 02138, USA article info abstract Article history: Qafzeh Cave, the burial grounds of several anatomically modern humans, producers of Mousterian Received 7 March 2008 industry, yielded archaeological evidence reflecting their modern behavior. Dated to 92 ka BP, the lower Accepted 15 October 2008 layers at the site contained a series of hearths, several human graves, flint artifacts, animal bones, a collection of sea shells, lumps of red ochre, and an incised cortical flake. The marine shells were Keywords: recovered from layers earlier than most of the graves except for one burial. The shells were collected and Shell beads brought from the Mediterranean Sea shore some 35 km away, and are complete Glycymeris bivalves, Modern humans naturally perforated. Several valves bear traces of having been strung, and a few had ochre stains on Glycymeris insubrica them. Ó 2008 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Introduction and electron spin resonance (ESR) readings that placed both the Skhul and Qafzeh hominins in the range of 130–90 ka BP (Schwarcz Until a few years ago it was assumed that seashells were et al., 1988; Valladas et al., 1988; Mercier et al., 1993).