The Ingeborg, Tamara & Yonina Rennert Women in Judaism Forum Jewish Women Changing America: Cross Generational-Conversations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Jews, Gentiles, and the Modern Egalitarian Ethos

Jews, Gentiles, and the Modern Egalitarian Ethos: Some Tentative Thoughts David Berger The deep and systemic tension between contemporary egalitarianism and many authoritative Jewish texts about gentiles takes varying forms. Most Orthodox Jews remain untroubled by some aspects of this tension, understanding that Judaism’s affirmation of chosenness and hierarchy can inspire and ennoble without denigrating others. In other instances, affirmations of metaphysical differences between Jews and gentiles can take a form that makes many of us uncomfortable, but we have the legitimate option of regarding them as non-authoritative. Finally and most disturbing, there are positions affirmed by standard halakhic sources from the Talmud to the Shulhan Arukh that apparently stand in stark contrast to values taken for granted in the modern West and taught in other sections of the Torah itself. Let me begin with a few brief observations about the first two categories and proceed to somewhat more extended ruminations about the third. Critics ranging from medieval Christians to Mordecai Kaplan have directed withering fire at the doctrine of the chosenness of Israel. Nonetheless, if we examine an overarching pattern in the earliest chapters of the Torah, we discover, I believe, that this choice emerges in a universalist context. The famous statement in the Mishnah (Sanhedrin 4:5) that Adam was created singly so that no one would be able to say, “My father is greater than yours” underscores the universality of the original divine intent. While we can never know the purpose of creation, one plausible objective in light of the narrative in Genesis is the opportunity to actualize the values of justice and lovingkindness through the behavior of creatures who subordinate themselves to the will 1 of God. -

Sunday September 11 Will Be Sofer Day at Ohr Moshe. Please See Flyer for More Information

CONGREGATION OHR MOSHE Website: www.CongOhrMoshe.org Address: 170-16 73rd Ave. HONORARY GABBAI: Rabbi Moshe Berkowitz Asher Schechter, Rabbi Eli Siegel, Gabbai Additional Gabbaim: Sruly Beylus, [email protected] or 591-4888 g [email protected] or 718-969-4545 Tzvi Fisher, Hank Strom & Tal Zimm ANNOUNCEMENTS & EVENTS – SHABBOS PARSHAS RE”EH/ROSH CHODESH 9/3 Friday Evening, Candle Lighting 7:07, Mincha 7:00. Shabbos AM, Daf Yomi 8:15, Shacharis at 9 AM. Sof Zman Kriyas Shema: 9:39. MiniKiddush sponsored by Anonymous family for a Zchus of Refuah Shelayma for Cholei Yisrael. Chaburah at 6:05. Speaker for the last 15 minutes is R' Josh Meisner, topic: "A change of venue". Mincha at 7:05, followed by a Shiur by R' Shmuel Kosofsky, topic “Kavod HaBriyos in Hashkafa and Halacha”. Maariv at 8:15. Weekly Schedule: Sunday (Rosh Chodesh) Daf Yomi at 7:15 AM, Shacharis at 8 AM, Mincha & Maariv at 7:10 PM. Monday Labor Day on a Sunday Schedule. Thursday Shacharis at 6:20 AM, Tuesday Wednesday & Friday Shacharis at 6:30 AM. PLEASE MAKE YOUR BEST EFFORT TO JOIN US. We are saddened to announce the passing of Mr. David Tanzman, beloved father of Elaine Strasberg. Shiva will be observed through Wednesday AM at 169-10 73rd Avenue. Minyanim: Shacharis Sunday-Monday 8:00 AM Tuesday-Wednesday 7:00 AM. Mincha/Ma'ariv: Sunday-Tuesday 7:05 PM. HaMakom Yinachem Eschem.... Mazel Tov to Shimon and Chaya Cohen upon the birth of a baby boy. Shalom Zachor will be this Friday night at 9 PM at 75-24 168 street. -

Contemporaneity: Historical Presence in Visual Culture

Vol 8, No 1 (2019) | ISSN 2153-5914 (online) | DOI 10.5195/contemp/2019.286 http://contemporaneity.pitt.edu The Canaries of Democracy Imagining the Wandering Jew with Artist Rosabel Rosalind Kurth-Sofer Rae Di Cicco and Rosabel Rosalind Kurth-Sofer Introduction by Thomas M. Messersmith About the Authors Rae Di Cicco is a PhD candidate in the History of Art and Architecture Department at the University of Pittsburgh, specializing in Central European Modernism. Research for her dissertation, “The Body, the Kosmos, and the Other: The Cosmopolitan Imagination of Erika Giovanna Klien,” was supported by a Fulbright-Mach Fellowship in Austria in 2018-2019. The dissertation traces Klien’s career from her beginnings as a member of the Vienna-based modernist movement Kineticism (Kinetismus) to her immigration to the United States and subsequent work depicting indigenous groups of the American Southwest. Rosabel Rosalind Kurth-Sofer is an artist from Los Angeles. She graduated from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 2017 with a focus in printmaking, drawing, and painting. Rosabel received a Fulbright Combined Study-Research Grant in Austria for 2018-2019 to investigate Jewish caricatures in the Schlaff collection at the Jewish Museum Vienna. She currently lives in Chicago and continues to explore her Jewish identity through comics, poetry, and illustrated narratives. Thomas Messersmith is a PhD candidate at the University of Maryland, College Park. He was a recipient of the Fulbright-Mach Study Award in Austria for 2018-2019, where he conducted research for his dissertation, tentatively titled “‘God Rather than Men:’ Austrian Catholic Theology and the Development of Catholic Political Culture, 1848-1888.” This dissertation utilizes both lay and Church sources to explore the ways in which theological and political shifts in the late Habsburg Monarchy influenced each other, ultimately creating a new national and transnational Catholic political culture. -

The Marriage Issue

Association for Jewish Studies SPRING 2013 Center for Jewish History The Marriage Issue 15 West 16th Street The Latest: New York, NY 10011 William Kentridge: An Implicated Subject Cynthia Ozick’s Fiction Smolders, but not with Romance The Questionnaire: If you were to organize a graduate seminar around a single text, what would it be? Perspectives THE MAGAZINE OF THE ASSOCIATION FOR JEWISH STUDIES Table of Contents From the Editors 3 From the President 3 From the Executive Director 4 The Marriage Issue Jewish Marriage 6 Bluma Goldstein Between the Living and the Dead: Making Levirate Marriage Work 10 Dvora Weisberg Married Men 14 Judith Baskin ‘According to the Law of Moses and Israel’: Marriage from Social Institution to Legal Fact 16 Michael Satlow Reading Jewish Philosophy: What’s Marriage Got to Do with It? 18 Susan Shapiro One Jewish Woman, Two Husbands, Three Laws: The Making of Civil Marriage and Divorce in a Revolutionary Age 24 Lois Dubin Jewish Courtship and Marriage in 1920s Vienna 26 Marsha Rozenblit Marriage Equality: An American Jewish View 32 Joyce Antler The Playwright, the Starlight, and the Rabbi: A Love Triangle 35 Lila Corwin Berman The Hand that Rocks the Cradle: How the Gender of the Jewish Parent Influences Intermarriage 42 Keren McGinity Critiquing and Rethinking Kiddushin 44 Rachel Adler Kiddushin, Marriage, and Egalitarian Relationships: Making New Legal Meanings 46 Gail Labovitz Beyond the Sanctification of Subordination: Reclaiming Tradition and Equality in Jewish Marriage 50 Melanie Landau The Multifarious -

1 Jewish American Women's Writing: Dislodging Preconceptions By

Jewish American Women’s Writing: Dislodging Preconceptions by Challenging Expectations Judith Lewin Josh Lambert describes “a little experiment” that he does with his Jewish literature classes: “I ask them to take out a piece of paper and a pen or pencil…. I say, ‘Draw a Jew.’…. One of my favorite questions to ask first is this: ‘How many of you drew a woman?’ (Usually, it’s at most one or two…)” (paras.1-3). Since Lambert notes that “usually, it’s at most one or two,” the students’ inability to imagine a woman inhabiting the category “Jew” is worth dwelling upon.1 Why is it Jewish American women are invisible, inaudible, and insufficiently read? This essay proposes a curriculum that engages students to think broadly and fluidly about Jewish American women authors and the issues and themes in their fiction. Previous pedagogical essays on Jewish American women’s writing include two in sociology/women’s studies on identities (see Friedman and Rosenberg; Sigalow), Sheila Jelen’s in Shofar on Hebrew and Yiddish texts, and a special issue in MELUS 37:2 (Summer 2012) that include women’s literature but without gender as a focus. The aim of this essay, by contrast, is to introduce teachers of American literature to an array of texts written by American Jewish women that will engage critical reading, thinking and writing by contemporary college undergraduates. Two questions must be dealt with right away. First, how does one justify treating Jewish American women’s literature in isolation? Second, how does one challenge the expectations of what such a course entails? As Lambert demonstrated from his informal survey, Jewish women writers are doubly invisible, to Jewish literature as women and to 1 women’s literature as Jews. -

A Clergy Resource Guide

When Every Need is Special: NAVIGATING SPECIAL NEEDS IN A CONGREGATIONAL SETTING A Clergy Resource Guide For the best in child, family and senior services...Think JSSA Jewish Social Service Agency Rockville (Wood Hill Road), 301.838.4200 • Rockville (Montrose Road), 301.881.3700 • Fairfax, 703.204.9100 www.jssa.org - [email protected] WHEN EVERY NEED IS SPECIAL – NAVIGATING SPECIAL NEEDS IN A CONGREGATIONAL SETTING PREFACE This February, JSSA was privileged to welcome 17 rabbis and cantors to our Clergy Training Program – When Every Need is Special: Navigating Special Needs in the Synagogue Environment. Participants spanned the denominational spectrum, representing communities serving thousands throughout the Washington region. Recognizing that many area clergy who wished to attend were unable to do so, JSSA has made the accompanying Clergy Resource Guide available in a digital format. Inside you will find slides from the presentation made by JSSA social workers, lists of services and contacts selected for their relevance to local clergy, and tachlis items, like an ‘Inclusion Check‐list’, Jewish source material and divrei Torah on Special Needs and Disabilities. The feedback we have received indicates that this has been a valuable resource for all clergy. Please contact Rabbi James Kahn or Natalie Merkur Rose with any questions, comments or for additional resources. L’shalom, Rabbi James Q. Kahn, Director of Jewish Engagement & Chaplaincy Services Email [email protected]; Phone 301.610.8356 Natalie Merkur Rose, LCSW‐C, LICSW, Director of Jewish Community Outreach Email [email protected]; Phone 301.610.8319 WHEN EVERY NEED IS SPECIAL – NAVIGATING SPECIAL NEEDS IN A CONGREGATIONAL SETTING RESOURCE GUIDE: TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION 1: SESSION MATERIALS FOR REVIEW PAGE Program Agenda ......................................................................................................... -

Sefer Torah Shel Moshiach

להביא לימות המשיח Sefer Torah shel Moshiach לזכות דוד בן שיינא וזוגתו מרת פערל גאלדא בת לאה, ומשפחתם לוי, שניאור זלמן, מינא עטל, מאיר, וגבריאל נח שיקויים בהם ברכת כ"ק אדמו"ר להצלחה רבה ומופלגה במילוי שליחותם בשמפיין, איל. SHEVAT 5776 12 A CHASSIDISHER DERHER פרסום ראשון! NEVER BEFORE SEEN DOCUMENTS AND PHOTOGRAPHS LIGHT IN THE DARKNESS camps across Europe, although the Simchas Torah in Lubavitch is extent of the unbelievable destruction renowned for its lebedikeit and the was not apparent yet. It was during amazing energy the Rabbeim poured this dark time that the Frierdiker into the Chassidim. It is also a time Rebbe worked to uplift the spirits when the Rabbeim would often talk of the Yidden and to inspire them more openly to the Chassidim about to return to Hashem with complete projects or ideas that were very dear teshuva. These are the birth pangs of to them. Moshiach, he would say, and now an On the night of Simchas Torah opportune time to bring him and the 5702, during the farbrengen before complete geulah. hakafos, the Frierdiker Rebbe spoke With those few words the project to the Chassidim of writing a special to write a ‘Welcoming of Moshiach Sefer Torah with which to greet Sefer Torah’ began. At first the Moshiach. Frierdiker Rebbe was going to sponsor “With the help of Hashem and in the writing himself, as a private merit of my holy ancestors, I merited and personal secret, but then he to have the thought to become, bli reconsidered.2 “During the Simchas neder, a messenger of Torah meal, while speaking about the klal Yisrael to write a special Torah—‘The Welcoming of Moshiach Sefer Torah’—with which to (go out and) welcome Moshiach speedily in our d ay s .” 1 This was at the height of the Holocaust. -

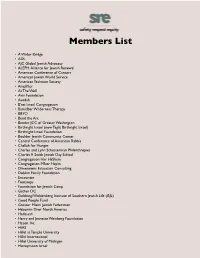

Members List Sre 2021

Members List • A Wider Bridge • ADL • AJC Global Jewish Advocacy • ALEPH: Alliance for Jewish Renewal • American Conference of Cantors • American Jewish World Service • American Technion Society • Amplifier • At The Well • Aviv Foundation • Avodah • B'nai Israel Congregation • Bamidbar Wilderness Therapy • BBYO • Bend the Arc • Bender JCC of Greater Washington • Birthright Israel (now Taglit Birthright Israel) • Birthright Israel Foundation • Boulder Jewish Community Center • Central Conference of American Rabbis • Challah for Hunger • Charles and Lynn Schusterman Philanthropies • Charles E Smith Jewish Day School • Congregation Har HaShem • Congregation M'kor Hayim • Dimensions Education Consulting • Dobkin Family Foundation • Encounter • Footsteps • Foundation for Jewish Camp • Gather DC • Goldring/Woldenberg Institute of Southern Jewish Life (ISJL) • Good People Fund • Greater Miami Jewish Federation • Habonim Dror North America • Hadassah • Harry and Jeanette Weinberg Foundation • Hazon, Inc. • HIAS • Hillel at Temple University • Hillel International • Hillel University of Michigan • Honeymoon Israel • iCenter • IKAR • Institute for Curriculum Services • International Institute for Secular Humanistic Judaism • IsraAID • Israel Institute • Israel on Campus Coalition • Israel Policy Forum • itrek • JCC Association of North America • JCFS Chicago • JDC • Jewish Community Center of Greater Pittsburgh • Jewish Community Federation and Endowment Fund • Jewish Community Foundation of Southern Arizona • Jewish Education Project • Jewish Family -

Amudim Community Resources, INC. Amount

Beis Community 2018 Amount: $7,000 Project: Women’s Leadership Development Amudim Community Resources, INC. • Supports women’s leadership development for Amount: $10,000 volunteers of an intentional and inclusive Project: Project Shmirah Orthodox Jewish community in Washington • Hold age-appropriate workshops in yeshivas Heights that attracts those traditionally on the and day schools to teach children about margins. healthy boundaries and strategies to increase emotional wellbeing. They will also provide Moving Traditions events in community centers, synagogues, and Amount: $60,000 homes that will encourage adults to become Project: National Jewish Summer Camp Healthy community advocates against abuse. Sexuality Initiative Center for Initiatives in Jewish Education (CIJE) • Moving Traditions will prepare two cohorts of Amount: $10,000 camp directors and assistant directors to train Project: YES I CAN their staff on bias prevention, harassment, and • Motivate, encourage, and support girls to peer pressure among staff and campers. pursue STEM education and careers through exposure to mentors and educational, T’ruah volunteer, and internship opportunities. Amount: $75,000 Additionally, CIJE will establish the YES I CAN Project: Development of Rabbinic Network career center which will establish STEM • Supports strengthening their rabbinic network internships and opportunities in the US and and training rabbis and cantors to be more Israel and offer assistance to young women effective leaders and to amplify the moral with college and scholarship applications. voice of the Jewish community. T’ruah will Jews for Racial and Economic Justice (JFREJ) develop trainings on anti-Semitism and Amount: $75,000 provide support to their network, particularly Project: Leadership Development women clergy, and promote the voices of • JWFNY’s unrestricted funds will support women as experts in teaching positions and leadership development and political journalism. -

Dngd Zkqn Massekhet Hahammah

dngd zkqn Massekhet HaHammah Compiled and Translated with Commentary by Abe Friedman A Project of the Commission on Social Justice and Public Policy of the Leadership Council of Conservative Judaism Rabbi Leonard Gordon, Chair [email protected] Table of Contents Preface i Introduction v Massekhet HaHammah 1. One Who Sees the Sun 1 2. Creation of the Lights 5 3. Righteous and Wicked 9 4. Sun and Sovereignty 15 5. The Fields of Heaven 20 6. Star-Worshippers 28 7. Astrology and Omens 32 8. Heavenly Praise 41 9. Return and Redemption 45 Siyyum for Massekhet HaHammah 51 Bibliography 54 Preface Massekhet HaHammah was developed with the support of the Commission on Social Justice and Public Policy of the Conservative Movement in response to the “blessing of the sun” (Birkat HaHammah), a ritual that takes place every 28 years and that will fall this year on April 8, 2009 / 14 Nisan 5769, the date of the Fast of the Firstborn on the eve of Passover. A collection of halakhic and aggadic texts, classic and contemporary, dealing with the sun, Massekhet HaHammah was prepared as a companion to the ritual for Birkat HaHammah. Our hope is that rabbis and communities will study this text in advance of the Fast and use it both for adult learning about this fascinating ritual and as the text around which to build a siyyum, a celebratory meal marking the conclusion of a block of text study and releasing firstborn in the community from the obligation to fast on the eve of the Passover seder.1 We are also struck this year by the renewed importance of our focus on the sun given the universal concern with global warming and the need for non-carbon-based renewable resources, like solar energy. -

The Song of Songs Seder: a Night of Sacred Sexuality by Rabbi Robert Teixeira, LCSW

The Song of Songs Seder: A Night of Sacred Sexuality By Rabbi Robert Teixeira, LCSW Many fault lines cut through the human family. The Sex-Is-Holy - Sex-Is-Dirty divide, which inflicts untold suffering on millions, is one of the widest and oldest. We find evidence of this divide in every faith tradition, including Judaism, where we encounter it numerous times in the Talmud, in reference to the Song of Songs, for example. This work, which revolves around the play of two Lovers, is by far the most erotic book in the Bible. According to the Talmud, the Song of Songs was set aside to be buried because of its sensual content (Avot De-Rabbi Nathan 1:4). These verses were singled out as particularly offensive: I am my beloved’s, and his desire is for me. Come, my beloved, let us go into the open; let us lodge among the henna shrubs. Let us go early to the vineyards; let us see if the vine has flowered, if its blossoms have opened, if the pomegranates are in bloom. There I will give my love to you.” (Song of Songs 7:11-13) At length, the rabbis debated whether to include the Song of Songs in the Bible. In their deliberations, they used the curious phrase “renders unclean the hands.” Holy books, in their view, were essentially “too hot to handle” on account of their intrinsic holiness. Handling them, then, renders unclean the hands, that is, makes one more or less untouchable, until specific rituals of purification are carried out. -

Commission on Social Action of Reform Judaism Religious Action Center of Reform Judaism

Commission on Social Action of Reform Judaism Religious Action Center of Reform Judaism Ethical Practices in Employing Domestic Workers I. Domestic Work in America A. Introduction to the Domestic Work Industry B. Current Federal and State Policy C. Policy Issues D. Recommendations II. Jewish Ethics and Domestic Work A. Texts and Values B. Reform Movement Policy III. Programming in Your Congregations A. Resources to use during Jewish Holidays B. Suggestions for Labor Practices and Ethical Decision Making Speaker Panel C. How to Conduct an Educational Forum D. Guiding Questions for Domestic Workers-“Living Talmud” E. Ethical Treatment of Workers Pledge IV. Additional Resources I. Domestic Work in America A. Introduction to the Domestic Work Industry Domestic workers are indispensable to the American economy. America’s families – including members of Reform congregations – depend on services provided by cleaning personnel, nannies, yard workers, and elder care workers. Domestic workers are common in American society. Yet, there are few laws governing their treatment and limited resources to assist families wrestling with the ethical issues that frequently arise around the employment of these workers. Jewish tradition and values can provide that ethical foundation and guidance for our congregants. The population of domestic workers employed throughout the country is unknown because it is difficult to survey workers in the informal labor sector. It is also hard to categorize domestic workers because the term “domestic worker” does not have a static definition. A domestic worker may or may not live in your home, may or may not be employed seasonally, and may perform any number of tasks not limited to helping with childcare, cooking, cleaning, and landscaping.