A Comparison Between the Union for Reform Judaism and the Israel Movement for Reform and Progress

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Why Jews Quote

Oral Tradition, 29/1 (2014):5-46 Why Jews Quote Michael Marmur Everyone Quotes1 Interest in the phenomenon of quotation as a feature of culture has never been greater. Recent works by Regier (2010), Morson (2011) and Finnegan (2011) offer many important insights into a practice notable both for its ubiquity and yet for its specificity. In this essay I want to consider one of the oldest and most diverse of world cultures from the perspective of quotation. While debates abound as to whether the “cultures of the Jews”2 can be regarded integrally, this essay will suggest that the act of quotation both in literary and oral settings is a constant in Jewish cultural creativity throughout the ages. By attempting to delineate some of the key functions of quotation in these various Jewish contexts, some contribution to the understanding of what is arguably a “universal human propensity” (Finnegan 2011:11) may be made. “All minds quote. Old and new make the warp and woof of every moment. There is not a thread that is not a twist of these two strands. By necessity, by proclivity, and by delight, we all quote.”3 Emerson’s reference to warp and woof is no accident. The creative act comprises a threading of that which is unique to the particular moment with strands taken from tradition.4 In 1 The comments of Sarah Bernstein, David Ellenson, Warren Zev Harvey, Jason Kalman, David Levine, Dow Marmur, Dalia Marx, Michal Muszkat-Barkan, and Richard Sarason on earlier versions of this article have been of enormous help. -

The Debate Over Mixed Seating in the American Synagogue

Jack Wertheimer (ed.) The American Synagogue: A Sanctuary Transformed. New York: Cambridge 13 University Press, 1987 The Debate over Mixed Seating in the American Synagogue JONATHAN D. SARNA "Pues have never yet found an historian," John M. Neale com plained, when he undertook to survey the subject of church seating for the Cambridge Camden Society in 1842. 1 To a large extent, the same situation prevails today in connection with "pues" in the American syn agogue. Although it is common knowledge that American synagogue seating patterns have changed greatly over time - sometimes following acrimonious, even violent disputes - the subject as a whole remains unstudied, seemingly too arcane for historians to bother with. 2 Seating patterns, however, actually reflect down-to-earth social realities, and are richly deserving of study. Behind wearisome debates over how sanctuary seats should be arranged and allocated lie fundamental disagreements over the kinds of social and religious values that the synagogue should project and the relationship between the synagogue and the larger society that surrounds it. As we shall see, where people sit reveals much about what they believe. The necessarily limited study of seating patterns that follows focuses only on the most important and controversial seating innovation in the American synagogue: mixed (family) seating. Other innovations - seats that no longer face east, 3 pulpits moved from center to front, 4 free (un assigned) seating, closed-off pew ends, and the like - require separate treatment. As we shall see, mixed seating is a ramified and multifaceted issue that clearly reflects the impact of American values on synagogue life, for it pits family unity, sexual equality, and modernity against the accepted Jewish legal (halachic) practice of sexual separatiop in prayer. -

A Synagogue for All Families: Interfaith Inclusion in Conservative Synagogues

A Synagogue for All Families Interfaith Inclusion in Conservative Synagogues Introduction Across North America, Conservative kehillot (synagogues) create programs, policies, and welcoming statements to be inclusive of interfaith families and to model what it means for 21st century synagogues to serve 21 century families. While much work remains, many professionals and lay leaders in Conservative synagogues are leading the charge to ensure that their community reflects the prophet Isaiah’s vision that God’s house “shall be a house of prayer for all people” (56:7). In order to share these congregational exemplars with other leaders who want to raise the bar for inclusion of interfaith families in Conservative Judaism, the United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism (USCJ) and InterfaithFamily (IFF) collaborated to create this Interfaith Inclusion Resource for Conservative Synagogues. This is not an exhaustive list, but a starting point. This document highlights 10 examples where Conservative synagogues of varying sizes and locations model inclusivity in marketing, governance, pastoral counseling and other key areas of congregational life. Our hope is that all congregations will be inspired to think as creatively as possible to embrace congregants where they are, and encourage meaningful engagement in the synagogue and the Jewish community. We are optimistic that this may help some synagogues that have not yet begun the essential work of the inclusion of interfaith families to find a starting point that works for them. Different synagogues may be in different places along the spectrum of welcoming and inclusion. Likewise, the examples presented here reflect a spectrum, from beginning steps to deeper levels of commitment, and may evolve as synagogues continue to engage their congregants in interfaith families. -

The Work of Who 1961

OFFICIAL RECORDS OF THE WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION No. 114 THE WORK OF WHO 1961 ANNUAL REPORT OF THE DIRECTOR -GENERAL TO THE WORLD HEALTH ASSEMBLY AND TO THE UNITED NATIONS Covering the Period 1 October 1960 - 31 December 1961 The Financial Report, 1 January -31 December 1961, which constitutes a supplementtothis volume,is published separately in the Official Records series. WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION GENEVA March 1962 The following abbreviations are used in the Official Records of the World Health Organization: ACABQ - Advisory Committee on Administrative and Budgetary Questions ACC - Administrative Committee on Co- ordination BTAO - Bureau of Technical Assistance Operations CCTA - Commission for Technical Co- operation in Africa South of the Sahara CIOMS - Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences ECA - Economic Commission for Africa ECAFE - Economic Commission for Asia and the Far East ECE - Economic Commission for Europe ECLA - Economic Commission for Latin America FAO - Food and Agriculture Organization IAEA - International Atomic Energy Agency ICAO - International Civil Aviation Organization ILO - International Labour Organisation (Office) IMCO - Inter - Governmental Maritime Consultative Organization ITU - International Telecommunication Union MESA - Malaria Eradication Special Account OIHP - Office International d'Hygiène Publique PAHO - Pan American Health Organization PASB - Pan American Sanitary Bureau SMF - Special Malaria Fund of PAHO TAB - Technical Assistance Board TAC - Technical Assistance Committee UNESCO -

Jesus & the Jewish Wedding Ceremony Pt.2

Issue July-August 2018 / Av-Elul 5778 The Zion Letter The Monthly Newsletter of For Zion’s Sake Ministries, Inc. PO Box 1486 Bristol, TN 37620 www.forzionsake.org Phone: 276-644-1678 * Fax: 276-644-1689 * Email: [email protected] * Web: www.forzionsake.org Jesus & The Jewish Wedding Ceremony, Part 2 In last month's Zion Letter, we saw that Jesus followed the “Baruch Haba Bashem Adonai” (Blessed is He who pattern of the ancient Jewish wedding through the Erusin comes in the name of the Lord). (betrothal) stage. You may recall the words of Paul in 2Cor.11:2, "For I am jealous for you with a godly jeal- You may recall the word of Yeshua (Jesus) in Matthew ousy; for I betrothed you to one husband, that to Messiah I 23:37-39, when He said, "O Jerusalem, Jerusalem, who might present you as a pure virgin." Beloved, we are kills the prophets and stones those who are sent to her! How merely betrothed to Messiah in this life. Our wedding cer- often I wanted to gather your children together the way a emony and our bridegroom are yet to come! hen gathers her chicks under her wings and you were un- willing. Behold your house is being left to you desolate! For The ancient Jewish wedding ceremony had two parts: I say to you, from now on you shall not see Me until you Erusin (betrothal) and Nissuin (wedding). In Biblical say, ‘Blessed is He who comes in the name of the Lord’!” times, the two parts were held separately. -

Conversion to Judaism Finnish Gerim on Giyur and Jewishness

Conversion to Judaism Finnish gerim on giyur and Jewishness Kira Zaitsev Syventävien opintojen tutkielma Afrikan ja Lähi-idän kielet Humanistinen tiedekunta Helsingin yliopisto 2019/5779 provided by Helsingin yliopiston digitaalinen arkisto View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk CORE brought to you by Tiedekunta – Fakultet – Faculty Koulutusohjelma – Utbildningsprogram – Degree Programme Humanistinen tiedekunta Kielten maisteriohjelma Opintosuunta – Studieinriktning – Study Track Afrikan ja Lähi-idän kielet Tekijä – Författare – Author Kira Zaitsev Työn nimi – Arbetets titel – Title Conversion to Judaism. Finnish gerim on giyur and Jewishness Työn laji – Aika – Datum – Month and year Sivumäärä– Sidoantal Arbetets art – Huhtikuu 2019 – Number of pages Level 43 Pro gradu Tiivistelmä – Referat – Abstract Pro graduni käsittelee suomalaisia, jotka ovat kääntyneet juutalaisiksi ilman aikaisempaa juutalaista taustaa ja perhettä. Data perustuu haastatteluihin, joita arvioin straussilaisella grounded theory-menetelmällä. Tutkimuskysymykseni ovat, kuinka nämä käännynnäiset näkevät mitä juutalaisuus on ja kuinka he arvioivat omaa kääntymistään. Tutkimuseni mukaan kääntyjän aikaisempi uskonnollinen tausta on varsin todennäköisesti epätavallinen, eikä hänellä ole merkittäviä aikaisempia juutalaisia sosiaalisia suhteita. Internetillä on kasvava rooli kääntyjän tiedonhaussa ja verkostoissa. Juutalaisuudessa kääntynyt näkee tärkeimpänä eettisyyden sekä juutalaisen lain, halakhan. Kääntymisen nähdään vahvistavan aikaisempi maailmankuva -

Halachic and Hashkafic Issues in Contemporary Society 24 - Must a Kallah Cover Her Hair - Part 1 Ou Israel Center - Summer 2016

5776 - dbhbn ovrct [email protected] 1 sxc HALACHIC AND HASHKAFIC ISSUES IN CONTEMPORARY SOCIETY 24 - MUST A KALLAH COVER HER HAIR - PART 1 OU ISRAEL CENTER - SUMMER 2016 A] HAIR COVERING FOR MARRIED WOMEN A1] THE TORAH DERIVATION - SOTAH //// v tv Jt«r , t g rpU wv hbpk v tv , t i v«F v sh ng vu 1. jh:v rcsnc The head of the sotah was made ‘paru’a’ in public. What does ‘parua’ mean? ivk htbd atrv hukda ktrah ,ubck itfn 'v,uzck hsf tvrga ,ghke ,t r,ux - grpu 2. oa h"ar Rashi explains the expression ‘para’ to refer to untying the woman’s braids and learns from this that Jewish women must cover their head. How does he get from one to the other? grpu (jh:v rcsnc) unf ubukeu umna vkd,b /vkudn - gurp :h"ar) /o vhneC vmnJk i º«r&vt v´«g rp(h F tU·v g*rp h¬F o ºgv(, t Æv J«n tr³Hu 3. (vatv atr ,t vf:ck ,una Rashi clearly learns that the word ‘parua’ means ‘uncovered’. utk t,ga tuvvs kkfn grpu ch,fsn b"t ruxts kkfn vkguc kg ,utb,vk v,aga unf vsn sdbf vsn vkuubk hfv vk ibhscgsn 4. rehg ifu atr ,ugurp ,tmk ktrah ,ubc lrs iht vbhn gna ,uv vgurp /cg ,ucu,f h"ar Rashi on the Gemara gives two derivations for the halacha: (a) uncovering the woman’s hair was designed to be a public humiliation and thus we can infer that covering the hair in public is dignified; and (b) the need to uncover the hair of the married woman implies that married women’s hair was generally covered. -

American Jewish Yearbook

JEWISH STATISTICS 277 JEWISH STATISTICS The statistics of Jews in the world rest largely upon estimates. In Russia, Austria-Hungary, Germany, and a few other countries, official figures are obtainable. In the main, however, the num- bers given are based upon estimates repeated and added to by one statistical authority after another. For the statistics given below various authorities have been consulted, among them the " Statesman's Year Book" for 1910, the English " Jewish Year Book " for 5670-71, " The Jewish Ency- clopedia," Jildische Statistik, and the Alliance Israelite Uni- verselle reports. THE UNITED STATES ESTIMATES As the census of the United States has, in accordance with the spirit of American institutions, taken no heed of the religious convictions of American citizens, whether native-born or natural- ized, all statements concerning the number of Jews living in this country are based upon estimates. The Jewish population was estimated— In 1818 by Mordecai M. Noah at 3,000 In 1824 by Solomon Etting at 6,000 In 1826 by Isaac C. Harby at 6,000 In 1840 by the American Almanac at 15,000 In 1848 by M. A. Berk at 50,000 In 1880 by Wm. B. Hackenburg at 230,257 In 1888 by Isaac Markens at 400,000 In 1897 by David Sulzberger at 937,800 In 1905 by "The Jewish Encyclopedia" at 1,508,435 In 1907 by " The American Jewish Year Book " at 1,777,185 In 1910 by " The American Je\rish Year Book" at 2,044,762 DISTRIBUTION The following table by States presents two sets of estimates. -

Conversion to Judaism After the Shoa

Barbara J. Steiner Between Guilt and Repression – Conversion to Judaism after the Shoa Conversion to Judaism and the subsequent acceptance of Jewish converts are topics that are still discussed at length among Jews in Germany today. Is it actu- ally possible to become a Jew? How should a Jewish convert conduct herself or himself? And the most significant question of all: Why do non-Jewish Germans convert to Judaism, and what connection might this phenomenon have with Ger- many’s most recent past, the persecution of and murdering of Jews? Do Jewish converts simply want to change sides in order to belong to the victims and their successors, thereby distancing themselves from their own possibly disreputa- ble family histories? Do they simply want to make everything all right again? Do Germans who convert to Judaism do so because they feel guilty?¹ These are the questions that I will thoroughly investigate in my dissertation, which deals with the conversion of Germans to Judaism after 1945.² I intend to illustrate how German converts deal with the Shoa, and how far they integrate this into their biographies as ‘New Jews.’ From a religious perspective, it is possible for anyone to become a Jew. According to Halacha (the law of Judaism), a Jew is a person who is either born of a Jewish mother, or a person who has been converted to Judaism before a Beit Din (a Rabbinical court) after a period of religious instruction. Giur (the process of conversion) can take years, and is considered by many converts to be tiring and arbitrary.³ The conversion process is a test of the seriousness of the candidate; he or she must learn about the Jewish religion and Jewish history and make every effort to fit into the community. -

Aliyah and Settlement Process?

Jewish Women in Pre-State Israel HBI SERIES ON JEWISH WOMEN Shulamit Reinharz, General Editor Joyce Antler, Associate Editor Sylvia Barack Fishman, Associate Editor The HBI Series on Jewish Women, created by the Hadassah-Brandeis Institute, pub- lishes a wide range of books by and about Jewish women in diverse contexts and time periods. Of interest to scholars and the educated public, the HBI Series on Jewish Women fills major gaps in Jewish Studies and in Women and Gender Studies as well as their intersection. For the complete list of books that are available in this series, please see www.upne.com and www.upne.com/series/BSJW.html. Ruth Kark, Margalit Shilo, and Galit Hasan-Rokem, editors, Jewish Women in Pre-State Israel: Life History, Politics, and Culture Tova Hartman, Feminism Encounters Traditional Judaism: Resistance and Accommodation Anne Lapidus Lerner, Eternally Eve: Images of Eve in the Hebrew Bible, Midrash, and Modern Jewish Poetry Margalit Shilo, Princess or Prisoner? Jewish Women in Jerusalem, 1840–1914 Marcia Falk, translator, The Song of Songs: Love Lyrics from the Bible Sylvia Barack Fishman, Double or Nothing? Jewish Families and Mixed Marriage Avraham Grossman, Pious and Rebellious: Jewish Women in Medieval Europe Iris Parush, Reading Jewish Women: Marginality and Modernization in Nineteenth-Century Eastern European Jewish Society Shulamit Reinharz and Mark A. Raider, editors, American Jewish Women and the Zionist Enterprise Tamar Ross, Expanding the Palace of Torah: Orthodoxy and Feminism Farideh Goldin, Wedding Song: Memoirs of an Iranian Jewish Woman Elizabeth Wyner Mark, editor, The Covenant of Circumcision: New Perspectives on an Ancient Jewish Rite Rochelle L. -

Family Tree Maker

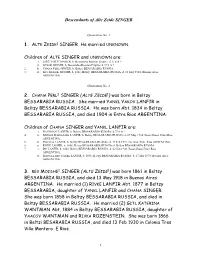

Descendants of Alte Zeide SINGER Generation No. 1 1. ALTE ZEIDE1 SINGER He married UNKNOWN. Children of ALTE SINGER and UNKNOWN are: i. JOILE YOILE2 SINGER, b. Bessarabia Russian Empire; d. U S A ?. ii. GUSSIE SINGER, b. Bessarabia Russian Empire; d. U S A ?. 2. iii. CHANA PERL SINGER, b. Beltzy BESSARABIA RUSSIA. 3. iv. REV MOISHE SINGER, b. 1861, Beltsy BESSARABIA RUSSIA; d. 13 May 1918, Buenos Aires ARGENTINA. Generation No. 2 2. CHANA PERL2 SINGER (ALTE ZEIDE1) was born in Beltzy BESSARABIA RUSSIA. She married YANKL YAKOV LANFIR in Beltzy BESSARABIA RUSSIA. He was born Abt. 1834 in Beltzy BESSARABIA RUSSIA, and died 1904 in Entre Rios ARGENTINA. Children of CHANA SINGER and YANKL LANFIR are: i. NACHMAN3 LANFIR, b. Beltzy BESSARABIA RUSSIA; d. U S A ?. 4. ii. MIRIAM MARIA LIBE LANFIR, b. Beltzy BESSARABIA RUSSIA; d. 07 May 1934, Basavilbaso Entre Rios ARGENTINA. 5. iii. PINCHAS LANFIR, b. Beltzy BESSARABIA RUSSIA; d. 27 Feb 1922, Escrinia Entre Rios ARGENTINA. 6. iv. RIVKE LANFIR, b. 1858, Beltzy BESSARABIA RUSSIA; d. Beltzy BESSARABIA RUSSIA. 7. v. ITE LANFIR, b. 1863, Beltzy BESSARABIA RUSSIA; d. 02 Jun 1943, Basavilbaso Entre Rios ARGENTINA. vi. MANUEL BEN YANKL LANFIR, b. 1891, Beltzy BESSARABIA RUSSIA; d. 27 Mar 1979, Buenos Aires ARGENTINA. 3. REV MOISHE2 SINGER (ALTE ZEIDE1) was born 1861 in Beltsy BESSARABIA RUSSIA, and died 13 May 1918 in Buenos Aires ARGENTINA. He married (1) RIVKE LANFIR Abt. 1877 in Beltzy BESSARABIA, daughter of YANKL LANFIR and CHANA SINGER. She was born 1858 in Beltzy BESSARABIA RUSSIA, and died in Beltzy BESSARABIA RUSSIA. -

CCAR Journal the Reform Jewish Quarterly

CCAR Journal The Reform Jewish Quarterly Halachah and Reform Judaism Contents FROM THE EDITOR At the Gates — ohrgJc: The Redemption of Halachah . 1 A. Brian Stoller, Guest Editor ARTICLES HALACHIC THEORY What Do We Mean When We Say, “We Are Not Halachic”? . 9 Leon A. Morris Halachah in Reform Theology from Leo Baeck to Eugene B . Borowitz: Authority, Autonomy, and Covenantal Commandments . 17 Rachel Sabath Beit-Halachmi The CCAR Responsa Committee: A History . 40 Joan S. Friedman Reform Halachah and the Claim of Authority: From Theory to Practice and Back Again . 54 Mark Washofsky Is a Reform Shulchan Aruch Possible? . 74 Alona Lisitsa An Evolving Israeli Reform Judaism: The Roles of Halachah and Civil Religion as Seen in the Writings of the Israel Movement for Progressive Judaism . 92 David Ellenson and Michael Rosen Aggadic Judaism . 113 Edwin Goldberg Spring 2020 i CONTENTS Talmudic Aggadah: Illustrations, Warnings, and Counterarguments to Halachah . 120 Amy Scheinerman Halachah for Hedgehogs: Legal Interpretivism and Reform Philosophy of Halachah . 140 Benjamin C. M. Gurin The Halachic Canon as Literature: Reading for Jewish Ideas and Values . 155 Alyssa M. Gray APPLIED HALACHAH Communal Halachic Decision-Making . 174 Erica Asch Growing More Than Vegetables: A Case Study in the Use of CCAR Responsa in Planting the Tri-Faith Community Garden . 186 Deana Sussman Berezin Yoga as a Jewish Worship Practice: Chukat Hagoyim or Spiritual Innovation? . 200 Liz P. G. Hirsch and Yael Rapport Nursing in Shul: A Halachically Informed Perspective . 208 Michal Loving Can We Say Mourner’s Kaddish in Cases of Miscarriage, Stillbirth, and Nefel? . 215 Jeremy R.