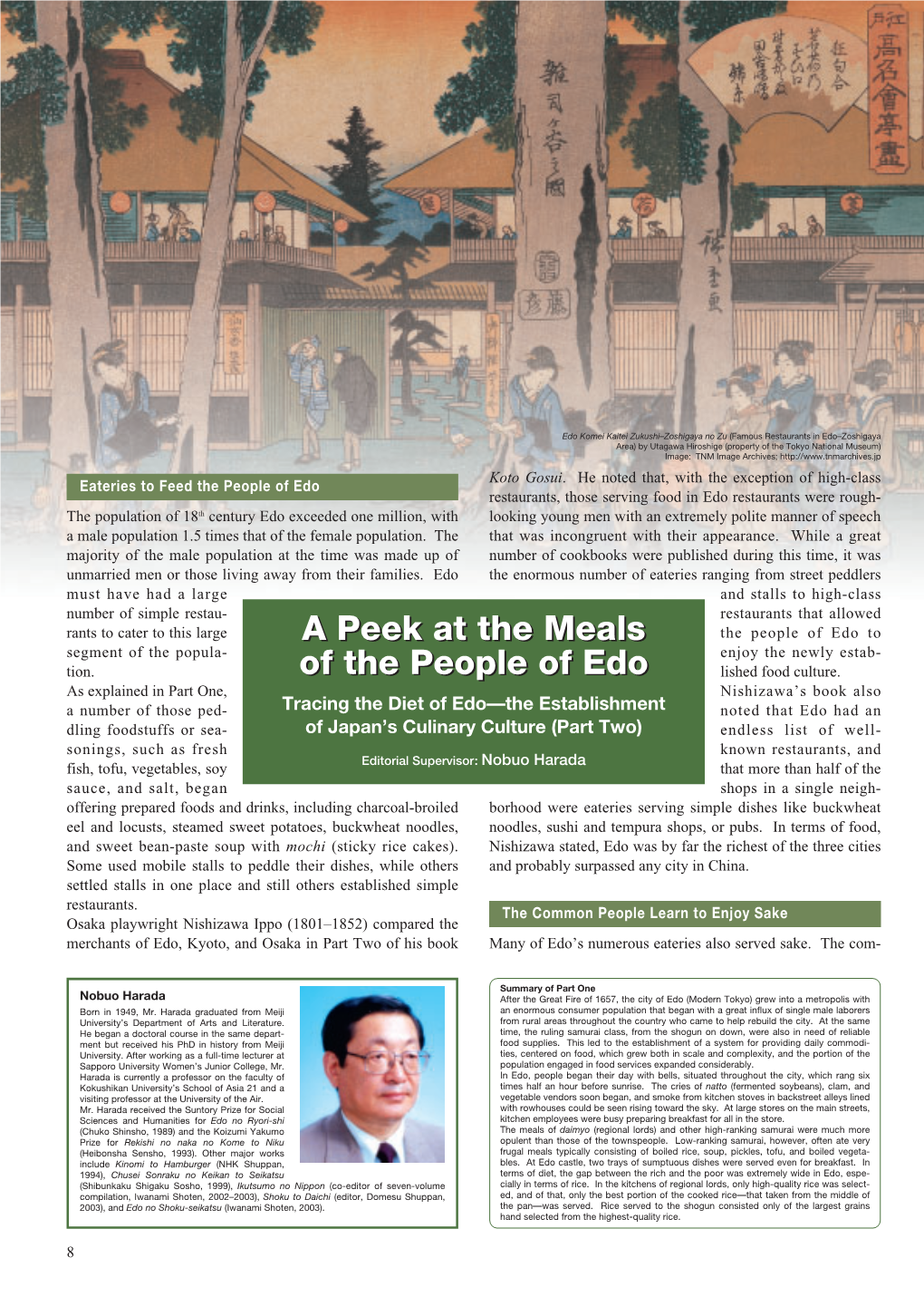

A Peek at the Meals of the People of Edo Tracing the Diet Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nihonbashi: Edo's Contested Center Marcia Yonemoto

, East Asian History NUMBERS 17/18· JUNE/DECEMBER 1999 Institute of Advanced Studies Australian National University 1 Editor Geremie R. Barme Assistant Editor Helen Lo Editorial Board Mark Elvin (Convenor) John Clark Andrew Fraser Helen Hardacre Colin Jeffcott W. ]. F. Jenner Lo Hui-min Gavan McCormack David Marr Tessa Morris-Suzuki Michael Underdown Design and Production Helen Lo Business Manager Marion Weeks Printed by Goanna Print, Fyshwick, ACT This double issue of East Asian History, 17/18, was printed in FebrualY 2000. Contributions to The Editor, East Asian History Division of Pacific and Asian History Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Phone +61 26249 3140 Fax +61 26249 5525 email [email protected] Subscription Enquiries to Subscriptions, East Asian History, at the above address Annual Subscription Australia A$45 Overseas US$45 (for two issues) iii CONTENTS 1 Whose Strange Stories? P'u Sung-ling (1640-1715), Herbert Giles (1845- 1935), and the Liao-chai chih-yi John Minford and To ng Man 49 Nihonbashi: Edo's Contested Center Marcia Yonemoto 71 Was Toregene Qatun Ogodei's "Sixth Empress"? 1. de Rachewiltz 77 Photography and Portraiture in Nineteenth-Century China Regine Thiriez 103 Sapajou Richard Rigby 131 Overcoming Risk: a Chinese Mining Company during the Nanjing Decade Ti m Wright 169 Garden and Museum: Shadows of Memory at Peking University Vera Schwarcz iv Cover calligraphy Yan Zhenqing M.c�J�n, Tang calligrapher and statesman Cover illustration Talisman-"Passport for wandering souls on the way to Hades," from Henri Dore, Researches into Chinese superstitions (Shanghai: T'usewei Printing Press, 1914-38) NIHONBASHI: EDO'S CONTESTED CENTER � Marcia Yonemoto As the Tokugawa 11&)II regime consolidated its military and political conquest Izushi [Pictorial sources from the Edo period] of Japan around the turn of the seventeenth century, it began the enormous (Tokyo: Chikuma Shobo, 1975), vol.4; project of remaking Edo rI p as its capital city. -

The Small Details Group Dining & Events

THE SMALL DETAILS GROUP DINING & EVENTS AT DRAGONFLY SUSHI & SAKÉ COMPANY WE ARE PASSIONATE ABOUT CREATING MEANINGFUL CONNECTIONS. Our group dining packages are designed to help you build stronger friendships, celebrate memories and bring out the very best in your group as they gather around the table at Dragonfly. DRAGONFLY 3 THE SMALL DETAILS - CONTENTS FOOD MENUS Fresh selections SHOGUN MENU EMPEROR MENU from farm and sea IZAKAYA FAMILY STYLE IZAKAYA FAMILY STYLE prepared Izakaya (family) style. Creating artful flavors. Anchoring your event. Izakaya is a tapas-style dining Izakaya is a tapas-style dining Sewing friendships tighter. experience that encourages joy experience that encourages joy BEVERAGE MENU Bringing your friends, colleagues, and fulfillment through and fulfillment through family closer together. sharing and conversation. sharing and conversation. Spirited concoctions and unexpected combinations to lighten the mood. 4 guest minimum 4 guest minimum Setting the scene for an evening of relaxation, enjoyment and conversation. $65 $85 $22 $24 $27 $32 PAGE 4 PAGE 5 PAGE 6-7 * per person price does not include 20% gratuity and 7% sales tax Looking for a more exclusive experience? Total buyouts, private luncheons & sushi classes are available, please contact us for more details. DRAGONFLY 4 IZAKAYA-SHOGUN MENU STARTERS SUSHI BUTTER SAUTÉED EDAMAME CLASSIC ROLL togarashi, sea salt, bonito flakes baked, tuna, albacore, seasonal white fish, scallions, spicy sauce, eel sauce SHISO PRETTY tuna tartare, scallion, spicy mayo— COBRA KAI ROLL wrapped in shiso leaf & flash fried krab delight, red onion, tomato, tempura flakes, lemon, salmon, WONTONS garlic-shiso pesto, aged balsamic krab, cream cheese, peach-apricot reduction “THE BOMB” ROLL tuna, tempura shrimp, krab delight, BEEF TATAKI avocado, tempura flakes, eel sauce, seared n.y. -

Quantunque Sia Citato Nei Compendi Di Storia Del Giappone, Al V Shōgun Della Casata Tokugawa, Tsunayoshi

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by AIR Universita degli studi di Milano Rivista degli Studi Orientali - Università L a Sapienza in Roma VOL. LXXXII, 2009 VIRGINIA SICA * TOKUGAWA TSUNAYOSHI. PROVE GENERALI DI STATO SOCIALE «… questa, però, non è una storia di animali, Signora Winter.» «Già, suppongo sia sbagliato di parlare di “animali”. La vita è una.» […] La terra è stanca di belve, e già questa natura, tanto temuta, ha piccoli figli di pace, allatta creature della dolcezza di Alonso, mentre noi nascondiamo o cancelliamo senza vergogna la grazia dell’uomo. […] Quel dio che si aggira ancora oggi, stremato, per le petraie del mondo. Esse sono infinite, Signore, esse rendono illusori e beffardi tutti i nostri campus, le nostre università. […] sarebbero opportune disposizioni in merito all’acqua da consegnare a tutti coloro che ardono dalla sete, criminali, poveri, e ogni genere di nemico, in cui Egli potrebbe essersi momentaneamente, per aver aiuto, trasformato. Dovunque, Signore, l’acqua di Dio è oggi carente – dovunque si ha sete. Date acqua, per carità, senza sale né minacce di morte. Anna Maria Ortese, Alonso e i visionari 1 Quantunque sia citato nei compendi di storia del Giappone, al V shōgun della casata Tokugawa, Tsunayoshi (1646-1709), è d‟abitudine riservato un fugace spazio, circoscritto a scarni riferimenti ad una presunta personalità tirannica e instabile, e a legiferazioni indebitamente ricordate come misure a sola tutela dei cani che, come narra il gossip della Storia, avrebbero avuto preminenza assoluta sull‟indirizzo legislativo dell‟epoca. Questo narrato ben si inscrive nella rinomata eccentricità dell‟era Genroku (1688-1703), consegnataci come la più intemperante di periodo Edo (1603-1867), perché contrassegnata dalla cultura del lusso, dell‟edonismo, e un eccesso di disinvoltura nell‟etica sociale. -

Part 3 TRADITIONAL JAPANESE CUISINE

Part 3 TRADITIONAL JAPANESE CUISINE Chakaiseki ryori is one of the three basic styles of traditional Japanese cooking. Chakaiseki ryori (the name derives from that of a warmed stone that Buddhist monks placed in the front fold of their garments to ward off hunger pangs) is a meal served during a tea ceremony. The foods are fresh, seasonal, and carefully prepared without decoration. This meal is then followed by the tea ceremony. (Japan, an Illustrated Encyclopedia , 1993, p. 1538) Honzen ryori is one of the three basic styles of traditional Japanese cooking. Honzen ryori is a highly ritualized form of serving food in which prescribed types of food are carefully arranged and served on legged trays (honzen). Honzen ryori has its main roots in the so- called gishiki ryori (ceremonial cooking) of the nobility during the Heian period (794 - 1185). Although today it is seen only occasionally, chiefly at wedding and funeral banquets, its influence on modern Japanese cooking has been considerable. The basic menu of honzen ryori consists of one soup and three types of side dishes - for example, sashimi (raw seafood), a broiled dish of fowl or fish (yakimono), and a simmered dish (nimono). This is the minimum fare. Other combinations are 2 soups and 5 or 7 side dishes, or 3 soups and 11 side dishes. The dishes are served simultaneously on a number of trays. The menu is designed carefully to ensure that foods of similar taste are not served. Strict rules of etiquette are followed concerning the eating of the food and drinking of the sake. -

The Durability of the Bakuhan Taisei Is Stunning

Tokugawa Yoshimune versus Tokugawa Muneharu: Rival Visions of Benevolent Rule by Tim Ervin Cooper III A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Mary Elizabeth Berry, Chair Professor Irwin Scheiner Professor Susan Matisoff Fall 2010 Abstract Tokugawa Yoshimune versus Tokugawa Muneharu: Rival Visions of Benevolent Rule by Tim Ervin Cooper III Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor Mary Elizabeth Berry, Chair This dissertation examines the political rivalry between the eighth Tokugawa shogun, Yoshimune (1684‐1751, r. 1716‐45), and his cousin, the daimyo lord of Owari domain, Tokugawa Muneharu (1696‐1764, r. 1730‐39). For nearly a decade, Muneharu ruled Owari domain in a manner that directly contravened the policies and edicts of his cousin, the shogun. Muneharu ignored admonishments of his behavior, and he openly criticized the shogun’s Kyōhō era (1716‐36) reforms for the hardship that they brought people throughout Japan. Muneharu’s flamboyance and visibility transgressed traditional status boundaries between rulers and their subjects, and his lenient economic and social policies allowed commoners to enjoy the pleasures and profits of Nagoya entertainment districts that were expanding in response to the Owari lord’s personal fondness for the floating world. Ultimately, Muneharu’s fiscal extravagance and moral lenience—benevolent rule (jinsei), as he defined it—bankrupted domain coffers and led to his removal from office by Yoshimune. Although Muneharu’s challenge to Yoshimune’s political authority ended in failure, it nevertheless reveals the important role that competing notions of benevolence (jin) were coming to play in the rhetoric of Tokugawa rulership. -

Menupro Dinner 2020

RED WINE BY THE GLASS Cabernet, Roth Estates, Alexander Valley ................................. $13 Pinot Noir, Acrobat, Oregon ........................................................ $11 Cabernat Sauvignon, Alexander Valley ...................................... $10 Bordeaux Rouge, Chateau Recougne ............................................ $9 Super Tuscan, Tommasi "Poggio Al Tufo" .................................. $8 Rioja Tempranillo, Equia, Spain ...................................................... $7 Malbec, Pascual Toso Agentina ...................................................... $7 Merlot, Hayes Ranch California ..................................................... $7 Cabernet Sauvignon, Bodega Norton Agentina ......................... $7 WHITE WINE BY THE GLASS Sauvignon Blanc, J. Christopher Willamette Valley ............... $12 Chardonnay, Ferrari Carano Alexander Valley ........................ $12 Dry Riesling, Trefethen Estate Napa .......................................... $11 Pinot Gris, Ponzi Vineyards, Willamette Valley ........................ $10 Pinot Grigio, Marco Felluga, Collio, Italy .................................... $9 Dry Riesling , Dr. loosen, Mosel Germanay .............................. $9 Chardonnay unoak, Lincourt Santa Barbara ............................... $8 Gewurztraminer, Villa Wolf Germany ......................................... $8 Chardonnay, Guenoc Lake County CA ....................................... $7 Rose, Gassier, Provence ................................................................ -

Beer Draught Draught Sake & Spirits Sake Junmai Daiginjo Ginjo Specialty Cocktails Mexico Asia Sumo Classics Sparkling

BEER DRAUGHT BLUE MOON | 6 COORS LIGHT | 6 KIRIN | 7 NEGRA MODELO | 7 PACIFICO | 7 SAPPORO | 7 805 CERVEZA | 7 LAGUNITAS IPA | 7 ‘MAKE IT’ A CUCUMBER AGUACHILE MICHELADA | 3 DRAUGHT SAKE & SPIRITS SHO CHIKU BAI — HOT SAKE (3 OZ/9 OZ CARAFE) | 6/17 PATRON SILVER | 12 TITOS | 12 SAKE JUNMAI SWORD OF THE SUN TOKUBETSU HONJOZO 300ML | 32 BAN RYU HONJOZO 720ML | 8/22/50 TOZAI LIVING JEWEL 720ML | 32 DANCE OF THE DISCOVERY* 720ML | 54 JOTO ‘THE GREEN ONE’ 720ML | 46 HIRO ‘BLUE’ JUNMAI GINJO 300ML | 6/26 TY KU SILVER 720ML | 7/20/40 KUROSAWA 720ML | 60 WATER GOD 720ML | 90 DAIGINJO JOTO ‘ONE WITH CLOCKS’ 720ML | 72 BIG BOSS 720ML | 90 SILENT STREAM 720ML | 250 PURE DAWN 720ML | 15/30/60 GINJO CABIN IN THE WOODS 720ML | 10/36/72 FUKUCHO ‘MOON ON THE WATER’ 720ML | 78 KANBARA ‘BRIDE OF THE FOX’ 720ML | 70 DEMON SLAYER 720ML | 120 RIHAKU ‘WANDERING POETS’ 720ML | 58 TOSATURU DEEP WATER AZURE 7 720ML | 12/34/70 SPECIALTY HOU HOU SHU SPARKLING 300ML | 33 JOTO ‘THE BLUE ONE’ NIGORI 720ML | 62 RIHAKU ‘DREAMY CLOUDS’ NIGORI 720ML | 68 MOONSTONE COCONUT LEMONGRASS 750ML | 7/22/45 BLOSSOM OF PEACE 720ML | 38 SAYURI ‘WHITE CRANE’ NIGORI 720ML | 8/22/50 COCKTAILS MEXICO BUBBLES AND FLOWERS | 14 Passion fruit, champagne, hibiscus + butterfly pea flower MEXICAN SWIZZLE | 16 Tequila silver, Ancho Reyes, Mr. Black, watermelon + cinnamon syrup OAXACAN OLD FASHIONED | 16 Reposado tequila, amaro liquor aperitif + demerara simple syrup ASIA MUCHO GRANDE UMAMI MARTINI | 18 Enoki mushroom infused japanese gin, dry sake, Pocari sweat water KEMURI | 16 Japanese whiskey, -

The Trouble with Terasaka: the Forty-Seventh Ro¯Nin and the Chu¯Shingura Imagination

Japan Review, 2004, 16:3-65 The Trouble with Terasaka: The Forty-Seventh Ro¯nin and the Chu¯shingura Imagination Henry D. SMITH II Columbia University, New York, NY, U.S.A. Most historians now agree that there were forty-seven ro¯nin of Ako¯ who attacked and killed Kira Yoshinaka in Edo in the twelfth month of 1702, twenty-two months after their lord had been put to death for his own failed attempt on Kira’s life. In the immediate wake of the attack, however, Terasaka Kichiemon—the lowest-ranking member of the league and the only one of ashigaru (foot soldier) status—was separated from the other forty-six, all of whom surrendered to the bakufu authorities and were subsequently executed. Terasaka provided rich material in the eighteenth century for play- wrights and novelists, particularly in the role of Teraoka Heiemon in Kanadehon Chu¯shingura of 1748 (one year after the historical Terasaka’s death at the age of eighty-three). In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Terasaka became an increasingly more controversial figure in debates over his qualifications as a true “Gishi” (righteous samurai), and hence whether there were really “Forty-Seven Ro¯nin” or only forty-six. This essay traces both the literary transformations of Terasaka and the debates over his place in history, arguing that his marginal status made him a constant source of stimulus to the “Chu¯shingura imagination” that has worked to make the story of the Ako¯ revenge so popular, and at the same time a “troubling” presence who could be interpreted in widely different ways. -

Geographies of Identity. David. L. Howell.Pdf

Geographies of Identity in Nineteenth-Century Japan Geographies of Identity in Nineteenth-Century Japan David L. Howell UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS Berkeley . Los Angeles . London University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England © 2005 by the Regents of the University of California Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Howell, David L. Geographies of identity in nineteenth-century Japan / David L. Howell. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-520-24085-5 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Japan—Civilization—19th century. 2. Japan— Social conditions—19th century. 3. Ainu—Ethnic identity. I. Title. ds822.25.h68 2005 306'.0952'09034—dc22 2004009387 Manufactured in the United States of America 14 13 12 11 10 09 08 07 06 05 10987654 321 The paper used in this publication is both acid-free and totally chlorine-free (TCF). It meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48–1992 (R 1997) (Permanence of Paper). Contents List of Maps vi Acknowledgments vii 1. Introduction 1 2. The Geography of Status 20 3. Status and the Politics of the Quotidian 45 4. Violence and the Abolition of Outcaste Status 79 5. Ainu Identity and the Early Modern State 110 6. The Geography of Civilization 131 7. Civilization and Enlightenment 154 8. Ainu Identity and the Meiji State 172 Epilogue: Modernity and Ethnicity 197 Notes 205 Works Cited 237 Index 255 Maps Japan 2 Territory of the outcaste headman Suzuki Jin’emon 38 Hokkaido 111 vi Acknowledgments In the long course of writing this book I accumulated sizable intellectual debts to numerous institutions and individuals. -

A5 MENU GENERIC SUMMER 2019 FINAL.Indd

THE ‘MOSHIMO’ SUSHI BOAT A selection of our sushi and sashimi for larger groups and parties, beautifully served on bamboo boats. Just let us know how much you want to spend (£40+) and let the chefs select the best sushi and sashimi for you, “omakase-style”* *subject to availability 微信掃碼 享中文菜單,看美食圖片 HOMEMADE JUICES & DRINKS WHITE WINE RED WINE We make our own homemade drinks, because they’re healthier and tastier - and Cuvee Jean Paul, Cotes De Gasgogne, Cuvee Jean Paul, Vaucluse, we’re through with unnecessary packaging France (vgn) £4.75/ £6.80/£19.90 France (vgn) £4.75/£6.80/£19.90 Fragrant nose with refreshing and zesty Grenache, Syrah and Merlot combine to give Fresh juice of the day (vgn) £4.50 green and citrus fruit flavours, a light this wine a soft, round and easy, gentle fruit appertif white that suits delicate spices style and a little spice on the finish Freshly made lemonade (vgn) £3.90 Les Oliviers Sauvignon Blanc Vermentino, Merlot Mourvedre, Les Oliviers, Ginger & lemon iced tea (vgn) £3.90 France (vgn) £5.35/£7.75/£22.40 France (vgn) £5.35/£7.75/£22.40 Zesty grapefruit character and a ripe full Soft and round with a touch of wild red Matcha iced tea (vgn) £3.50 texture balance berry and plum fruit flavours chosen to go with all but our most delicately flavoured of Matcha rice milk shake (vgn) £3.85 Fedele Catarratto Pinot Grigio, Sicily dishes Our own homemade rice milk mixed Italy (vgn/organic) £5.95/£8.55/£24.90 with the powdered green tea leaf used in Light, dry and a little ‘nutty’ a classic Italian Barbera Ceppi Storici, Italy (vgn) £24.90 Japanese tea ceremonies. -

ART, ARCHITECTURE, and the ASAI SISTERS by Elizabeth Self

ART, ARCHITECTURE, AND THE ASAI SISTERS by Elizabeth Self Bachelor of Arts, University of Oregon, 2007 Master of Arts, University of Pittsburgh, 2012 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Kenneth P. Dietrich School of the Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2017 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH THE KENNETH P. DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Elizabeth Self It was defended on April 6, 2017 and approved by Hiroshi Nara, Professor, East Asian Languages and Literatures Mrinalini Rajagopalan, Assistant Professor, History of Art and Architecture Katheryn Linduff, Professor Emerita, History of Art and Architecture Dissertation Advisor: Karen Gerhart, Professor, History of Art and Architecture ii Copyright © by Elizabeth Self 2017 iii ART, ARCHITECTURE, AND THE ASAI SISTERS Elizabeth Self, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2017 In early modern Japan, women, like men, used art and architectural patronage to perform and shape their identities and legitimate their authority. Through a series of case studies, I examine the works of art and architecture created by or for three sisters of the Asai 浅井 family: Yodo- dono 淀殿 (1569-1615), Jōkō-in 常高院 (1570-1633), and Sūgen-in 崇源院 (1573-1626). The Asai sisters held an elite status in their lifetimes, in part due to their relationship with the “Three Unifiers” of early 17th century Japan—Oda Nobunaga (1534-1582), Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1537- 1589), and Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543-1616). As such, they were uniquely positioned to participate in the cultural battle for control of Japan. In each of my three case studies, I look at a specific site or object associated with one of the sisters. -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2007/0212460 A1 Inoue Et Al

US 20070212460A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2007/0212460 A1 Inoue et al. (43) Pub. Date: Sep. 13, 2007 (54) COMPOSITIONS CONTAINING SUCRALOSE Nov. 25, 1998 (JP)...................................... 1198-333948 AND APPLICATION THEREOF Nov. 30, 1998 (JP). ... 1998-34O274 Dec. 11, 1998 (JP) 1998-3534.89 (75) Inventors: Maki Inoue, Osaka (JP); Kazumi Iwai, Dec. 11, 1998 (JP) 1998-3534.90 Osaka (JP): Naoto Ojima, Osaka (JP); Dec. 11, 1998 (JP). ... 1998-3534.92 Takuya Kawai, Osaka (JP); Mitsumi Dec. 11, 1998 (JP) 1998-353495 Kawamoto, Osaka (JP); Shunsuke Dec. 11, 1998 (JP) 1998-353496 Kuribi, Osaka (JP); Miho Sakaguchi, Dec. 11, 1998 (JP). ... 1998-353498 Osaka (JP); Chie Sasaki, Osaka (JP); Dec. 11, 1998 (JP). ... 1998-3534.99 Kazuhito Shizu, Osaka (JP); Mariko Dec. 11, 1998 (JP). ... 1998-3535O1 Shinguryou, Osaka (JP); Kazutaka Dec. 11, 1998 (JP). ... 1998-353503 Hirao, Osaka (JP); Miki Fujii, Osaka Dec. 11, 1998 (JP). ... 1998-353504 (JP); Yoshito Morita, Osaka (JP); Dec. 11, 1998 (JP) 1998-353505 Nobuharu Yasunami, Osaka (JP); Dec. 11, 1998 (JP) 1998-353507 Junko Yoshifuji, Osaka (JP) Jan. 26, 1999 (JP)......................................... 1999-16984 Jan. 26, 1999 (JP)......................................... 1999-16989 Correspondence Address: Jan. 26, 1999 (JP)......................................... 1999-16996 SUGHRUE, MION, ZINN, MACPEAK & Apr. 6, 1999 (JP). ... 1999-158511 SEAS, PLLC Apr. 6, 1999 (JP). ... 1999-158523 2100 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W. Apr. 6, 1999 (JP). ... 1999-158529 Washington, DC 20037-3202 (US) Apr. 6, 1999 (JP). ... 1999-158536 Apr. 6, 1999 (JP). ... 1999-158543 (73) Assignee: SAN-E GEN F.F.I., INC Apr. 6, 1999 (JP) 1999-158545 Apr.