Rakim, Ice Cube Then Watch the Throne: Engaged Visibility Through Identity Orchestration and the Language of Hip-Hop Narratives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

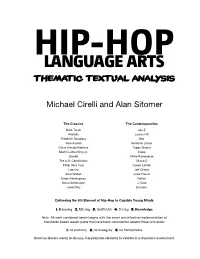

Language Arts Thematic Textual Analysis

HIP-HOPLANGUAGE ARTS THEMATIC TEXTUAL ANALYSIS Michael Cirelli and Alan Sitomer The Classics The Contemporaries Mark Twain Jay-Z Aristotle Lauryn Hill Frederick Douglass Nas Jane Austen Kendrick Lamar Oliver Wendell Holmes Tupac Shakur Martin Luther King Jr. Drake Gandhi Afrika Bambaataa The U.S. Constitution Chuck D Philip Vera Cruz Queen Latifah Lao-tzu Jeff Chang Alice Walker Lupe Fiasco Ernest Hemingway Rakim Sonia Sotomayor J. Cole Junot Díaz Eminem Delivering the 5th Element of Hip-Hop to Capable Young Minds 1. B-boying 2. MC-ing 3. Graffiti Art 4. DJ-ing 5. Knowledge Note: All work contained herein begins with the smart and effective implementation of standards-based lesson plans that have been constructed around three principles: 1. no profanity 2. no misogyny 3. no homophobia Great vocabulary words to discuss; inappropriate elements to validate in a classroom environment. HipHopLanguageArts3.indd 1 06/03/2015 15:38:37 2 | READ CLOSELY HIP-HOP INTERPRETATION GUIDE Question: Is violence ever an appropriate solution for resolving conflict? Consider the following text: from “Murder to Excellence” by Kanye West (with Jay-Z) I’m from the murder capital, where they murder for capital Heard about at least 3 killings this afternoon Lookin’ at the news like dang I was just with him after school, No shop class but half the school got a tool, And I could die any day type attitude Plus his little brother got shot reppin’ his avenue It’s time for us to stop and re-define black power 41 souls murdered in 50 hours 1. -

Runway Shows and Fashion Films As a Means of Communicating the Design Concept

RUNWAY SHOWS AND FASHION FILMS AS A MEANS OF COMMUNICATING THE DESIGN CONCEPT A thesis submitted to the College of the Arts of Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts By Xiaohan Lin July 2016 2 Thesis written by Xiaohan Lin B.S, Kent State University, 2014 M.A., Kent State University, 2016 Approved by ______________________________________________ Name, Thesis Supervisor ______________________________________________ Name, Thesis Supervisor or Committee Member ______________________________________________ Name, Committee Member ______________________________________________ Dr. Catherine Amoroso Leslie, Graduate Studies Coordinator, The Fashion School ______________________________________________ Dr. Linda Hoeptner Poling, Graduate Studies Coordinator, The School of Art ______________________________________________ Mr. J.R. Campbell, Director, The Fashion School ______________________________________________ Dr. Christine Havice, Director, The School of Art ______________________________________________ Dr. John Crawford-Spinelli, Dean, College of the Arts 3 REPORT OF THESIS FINAL EXAMINATION DATE OF EXAM________________________ Student Number_________________________________ Name of Candidate_______________________________________ Local Address_______________________________________ Degree for which examination is given_______________________________________ Department or School (and area of concentration, if any)_________________________ Exact title of Thesis_______________________________________ -

The Life & Rhymes of Jay-Z, an Historical Biography

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: THE LIFE & RHYMES OF JAY-Z, AN HISTORICAL BIOGRAPHY: 1969-2004 Omékongo Dibinga, Doctor of Philosophy, 2015 Dissertation directed by: Dr. Barbara Finkelstein, Professor Emerita, University of Maryland College of Education. Department of Teaching and Learning, Policy and Leadership. The purpose of this dissertation is to explore the life and ideas of Jay-Z. It is an effort to illuminate the ways in which he managed the vicissitudes of life as they were inscribed in the political, economic cultural, social contexts and message systems of the worlds which he inhabited: the social ideas of class struggle, the fact of black youth disempowerment, educational disenfranchisement, entrepreneurial possibility, and the struggle of families to buffer their children from the horrors of life on the streets. Jay-Z was born into a society in flux in 1969. By the time Jay-Z reached his 20s, he saw the art form he came to love at the age of 9—hip hop— become a vehicle for upward mobility and the acquisition of great wealth through the sale of multiplatinum albums, massive record deal signings, and the omnipresence of hip-hop culture on radio and television. In short, Jay-Z lived at a time where, if he could survive his turbulent environment, he could take advantage of new terrains of possibility. This dissertation seeks to shed light on the life and development of Jay-Z during a time of great challenge and change in America and beyond. THE LIFE & RHYMES OF JAY-Z, AN HISTORICAL BIOGRAPHY: 1969-2004 An historical biography: 1969-2004 by Omékongo Dibinga Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2015 Advisory Committee: Professor Barbara Finkelstein, Chair Professor Steve Klees Professor Robert Croninger Professor Derrick Alridge Professor Hoda Mahmoudi © Copyright by Omékongo Dibinga 2015 Acknowledgments I would first like to thank God for making life possible and bringing me to this point in my life. -

Central Saint Martins Fashion Fund

central saint martins fashion fund Fashion at Central Saint Martins (CSM) is internationally and critically acclaimed. The CSM Fashion Fund will provide programme- wide support for our students, equipment and facilities. The funds raised will contribute to the provision of the world-class education we are renowned for. As a thank-you for this support, we will invite donors to exclusive events and record their generosity in a visible area of the fashion studios. Richard Quinn, MA 2016 fashion inspiration St Martin’s School of Art was established in The internationally renowned centre for arts and design education has one of the most 1859. The first fashion course, headed by Muriel established reputations in fashion education Pemberton, started in 1932 and by the 1970s, and is considered a global leader in its field. St Martin’s School of Art was established, as one The Business of Fashion of the pre-eminent colleges for the study of The many individual careers and artistic contributions that were formed in the fashion. In 1989 St Martin’s joined the Central fashion department of Central Saint Martins School of Art and Design to become Central are well documented. Beyond those, though, Saint Martins College of Art and Design, bringing are a set of standards and a sense of cultural ambition that can’t be attributed to any one Fashion, Textiles and Jewellery Design together designer or teacher. And that’s what’s at the in the School of Fashion and Textile Design. In heart of its success and continuing relevance. It’s almost like an ideology. -

UNDERSTANDING PORTRAYALS of LAW ENFORCEMENT OFFICERS in HIP-HOP LYRICS SINCE 2009 By

ON THE BEAT: UNDERSTANDING PORTRAYALS OF LAW ENFORCEMENT OFFICERS IN HIP-HOP LYRICS SINCE 2009 by Francesca A. Keesee A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of George Mason University in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degrees of Master of Science Conflict Analysis and Resolution Master of Arts Conflict Resolution and Mediterranean Security Committee: ___________________________________________ Chair of Committee ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ Graduate Program Director ___________________________________________ Dean, School for Conflict Analysis and Resolution Date: _____________________________________ Fall Semester 2017 George Mason University Fairfax, VA University of Malta Valletta, Malta On the Beat: Understanding Portrayals of Law Enforcement Officers in Hip-hop Lyrics Since 2009 A Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degrees of Master of Science at George Mason University and Master of Arts at the University of Malta by Francesca A. Keesee Bachelor of Arts University of Virginia, 2015 Director: Juliette Shedd, Professor School for Conflict Analysis and Resolution Fall Semester 2017 George Mason University Fairfax, Virginia University of Malta Valletta, Malta Copyright 2016 Francesca A. Keesee All Rights Reserved ii DEDICATION This is dedicated to all victims of police brutality. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am forever grateful to my best friend, partner in crime, and husband, Patrick. -

Spiritualizing Hip Hop with I.C.E.: the Poetic Spiritual

SPIRITUALIZING HIP HOP WITH I.C.E.: THE POETIC SPIRITUAL NARRATIVES OF FOUR BLACK EDUCATIONAL LEADERS FROM HIP HOP COMMUNITIES by Alexis C. Maston A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Council of Texas State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy with a Major in Adult, Professional, and Community Education May 2014 Committee Members: Jovita Ross-Gordon, Co-Chair John Oliver, Co-Chair Ann K. Brooks Raphael Travis, Jr. COPYRIGHT by Alexis C. Maston 2014 FAIR USE AND AUTHOR’S PERMISSION STATEMENT Fair Use This work is protected by the Copyright Laws of the United States (Public Law 94-553, section 107). Consistent with fair use as defined in the Copyright Laws, brief quotations from this material are allowed with proper acknowledgement. Use of this material for financial gain without the author’s express written permission is not allowed. Duplication Permission As the copyright holder of this work I, Alexis C. Maston, authorize duplication of this work, in whole or in part, for educational or scholarly purposes only. DEDICATION This dissertation is first dedicated to my Lord and personal savior Jesus without whom this study would not have been possible. You are Alpha, Omega, the beginning and the end, and I went on this journey because you directed me to. Secondly, I dedicate this to my paternal and maternal grandparents, Fred and Emma Jean Maston, and Jacqueline Perkins, what you did years ago in your own lives made it possible for me to obtain this great opportunity. Thirdly, this dissertation is dedicated to Hip Hop communities worldwide who have always carried the essence of spirituality; this dissertation will uncover some of that truth. -

Mike Epps Slated As Host for This Year's BET HIP HOP AWARDS

Mike Epps Slated As Host For This Year's BET HIP HOP AWARDS G.O.O.D. MUSIC'S KANYE WEST LEADS WITH 17 IMPRESSIVE NOMINATIONS; 2CHAINZ FOLLOWS WITH 13 AND DRAKE ROUNDS THINGS OUT WITH 11 NODS SIX CYPHERS TO BE INCLUDED IN THIS YEAR'S AWARDS TAPING AT THE BOISFEUILLET JONES ATLANTA CIVIC CENTER IN ATLANTA ON SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 29, 2012; NETWORK PREMIERE ON TUESDAY, OCTOBER 9, 2012 AT 8:00 PM* NEW YORK, Sept. 12, 2012 /PRNewswire/ -- BET Networks' flagship music variety program, "106 & PARK," officially announced the nominees for the BET HIP HOP AWARDS (#HIPHOPAWARDS). Actor and comedian Mike Epps (@THEREALMIKEEPPS) will once again host this year's festivities from the Boisfeuillet Jones Atlanta Civic Center in Atlanta on Saturday, September 29, 2012 with the network premiere on Tuesday, October 9, 2012 at 8:00 pm*. Mike Epps completely took-over "106 & PARK" today to mark the special occasion and revealed some of the notable nominees with help from A$AP Rocky, Ca$h Out, DJ Envy and DJ Drama. Hip Hop Awards nominated artists A$AP Rocky and Ca$h Out performed their hits "Goldie" and "Cashin Out" while nominated deejay's DJ Envy and DJ Drama spun for the crowd. The BET HIP HOP AWARDS Voting Academy is comprised of a select assembly of music and entertainment executives, media and industry influencers. Celebrating the biggest names in the game, newcomers on the scene, and shining a light on the community, the BET HIP HOP AWARDS is ready to salute the very best in hip hop culture. -

LUXURY REVIEW Greater China

Issue No #01 2018 Issue No #01 LUXURY REVIEW Greater China [ 1 ] Welcome. Our quarterly Luxury Review has been given a new look. We aim to bring our What started as a passion project has grown readers the must-know to a must-read for industry insiders in China and beyond, and it’s only fitting that we facts and insights about the evolve our publication accordingly. luxury industry We have updated the format to accommodate time-pressed readers. We’ve introduced Quick Takes – short form articles to give you a recap of the key happenings in the luxury industry over the past quarter. You will still find our POV and analysis through longer reads in the second section. We have also merged our two editions into one bilingual issue. We will continue to cover trends, brands, and products having an impact on the Greater China region, from categories ranging from fashion and beauty to travel and auto – and wherever luxury will go next. We hope to continue to give you market knowledge and insights that will help guide your luxury communications strategy. Thank you for reading. Mindshare [ 2 ] Welcome. [ 3 ] Content 010 – Quick takes 011 – Campaigns 012 – Product Launches 013 – Business 014 – Content 015 – Technology 020 – Mindshare’s POV 021 – Chinese firms acquiring luxury brands 022 – Beauty is boosting speed to market 023 – WeChat’s new ad format 024 – Is J-Beauty the new K-beauty? 025 – Volvo’s luxury pivot brings recognition 026 – How can luxury brands thrive in today’s digital landscape? [ 4 ] TheQuick news Takes you need to keep up with luxury [ 5 ] CAMPAIGNS Chanel Mademoiselle Privé Exhibition Following two successful editions in London in 2015 and in Seoul last year, Chanel’s “Mademoiselle Privé” landed Hong Kong in early January this year. -

101 CC1 Concepts of Fashion

CONCEPT OF FASHION BFA(F)- 101 CC1 Directorate of Distance Education SWAMI VIVEKANAND SUBHARTI UNIVERSITY MEERUT 250005 UTTAR PRADESH SIM MOUDLE DEVELOPED BY: Reviewed by the study Material Assessment Committed Comprising: 1. Dr. N.K.Ahuja, Vice Chancellor Copyright © Publishers Grid No part of this publication which is material protected by this copyright notice may be reproduce or transmitted or utilized or store in any form or by any means now know or here in after invented, electronic, digital or mechanical. Including, photocopying, scanning, recording or by any informa- tion storage or retrieval system, without prior permission from the publisher. Information contained in this book has been published by Publishers Grid and Publishers. and has been obtained by its author from sources believed to be reliable and are correct to the best of their knowledge. However, the publisher and author shall in no event be liable for any errors, omission or damages arising out of this information and specially disclaim and implied warranties or merchantability or fitness for any particular use. Published by: Publishers Grid 4857/24, Ansari Road, Darya ganj, New Delhi-110002. Tel: 9899459633, 7982859204 E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] Printed by: A3 Digital Press Edition : 2021 CONTENTS 1. Introduction to Fashion 5-47 2. Fashion Forecasting 48-69 3. Theories of Fashion, Factors Affecting Fashion 70-96 4. Components of Fashion 97-112 5. Principle of Fashion and Fashion Cycle 113-128 6. Fashion Centres in the World 129-154 7. Study of the Renowned Fashion Designers 155-191 8. Careers in Fashion and Apparel Industry 192-217 9. -

Donna Karan Celebrated the Easy-Pieces Mantra on Which Ample Knits That Covered Cozy from Nordic to Aran to Homespun, the Latter in the Mulleavy She Founded Her House

PLUS HAIDER ACKERMANN SOCIAL MEDIA CRUSH BELLE CURVES MISSING MCQUEEN CHANEL’S ICEBERG ROAD TO TRADITION WWD BYE-BYE, BRYANT PARK COLLECTIONS CARDIN’S SPACE RACE CHRISTOPHER BAILEY Inspector Gadget A Top Ten: John Galliano is RICCARDO TISCI riding high at Givenchy’s Self-Made Man Christian Dior. L’WREN SCOTT Fearlessly Chic THE TRENDS PATCHWORK FUR NORDIC TRACK BLUSH HOUR PLAID TIMES VELVET CRUSH ARMY LIVES AND MORE The Top Ten FALL ’10 Collections 0412.COL.001.Cover.a;15.indd 1 4/6/10 8:42:43 PM You Choose vote for Your favorite designer P o P u L a r vote SPONSORED bY Make your favorite designer a winner at the 2010 CFDA Fashion Awards and be entered for a chance to win tickets to a New York Fashion Week show.* The CFDA Fashion Awards are a production of the Council of Fashion Designers of America. www.cfda.com vote now on *NO PURCHASE NECESSARY. To enter and for full rules, go to www.wwd.com/popular-vote. Starts 9:00 AM EST 4/1/10 and ends 11:59 PM EST 5/28/10. Open to legal residents of the 50 United States/D.C. 18 or older, except employees of Sponsor, their immediate families and those living in the same household. Odds of winning depend on the number of entries received. Void outside the 50 PHOTO BY STEVE EICHNER United States/D.C. and where prohibited. A.R.V. of prize $1,459.99: Sponsor: Condé Nast Publications. You Choose vote for Your favorite designer P o P u L a r vote SPONSORED bY Make your favorite designer a winner at the 2010 CFDA Fashion Awards and be entered for a chance to win tickets to a New York Fashion Week show.* The CFDA Fashion Awards are a production of the Council of Fashion Designers of America. -

Imhotep Hip Hop Issue.Pdf

A Treble Clef By The Students The By in Hip Hop Lyrics in Hip Hop Volume 9, May 2012 May 9, Volume IMHOTEP JOURNAL IMHOTEP A Discourse Analysis of Value Orientations Value of Analysis A Discourse IMHOTEP JOURNAL A Discourse Analysis of Value Orientations in Hip Hop Lyrics By The Students Volume 9 May 2012 (Blank Back of Front Cover) (Blank Back of Front Cover) San Francisco State University College of Ethnic Studies, Department Africana Studies Student Publications Imhotep Magazine Volume 1, February 2000 On Methodology Volume 2, February 2001 On African Philosophy Volume 3, February 2002 On African Education Ancient and Modern Volume 4, February 2003 Ideology of Race and Slavery from Antiquity to Modern Times Volume 5, May 2005 Essays on Ancient Egyptian Thought Volume 6, May 2008 African Rites of Passage Volume 7, May 2010 African Healing Traditions Volume 8, May 2011 African Ancestral Veneration Volume 9, May 2012 A Discourse Analysis of Value Orientations in Hip Hop Lyrics For further information contact: San Francisco State University College of Ethnic Studies, Department of Africana Studies 1600 Holloway Avenue San Francisco, California 94132 Tel: (415) 3381054 Fax: (415) 4050553 Editors Justin Metoyer and Christine Burke Production\ Design Kenric J. Bailey Contributors AFRS 111 Black Cultures and Personalities: 2008/9 Academic Year Faculty Advisor \ Co-Editor Serie McDougal, III, PhD We would like to express our thanks and appreciation to Madame Chair Dorothy Tsuruta PhD for her leadership and guidance, as well as the IRA for their support of this publication. Copyright © 2012 San Francisco State University All rights reserved. -

BICO Undergoing Restructuring Exercise

Established October 1895 New gender policy on the horizon Page 5 Friday February 20, 2015 $2 VAT Inclusive POTENTIAL FOR MORE EXPORTS THERE are several opportunities for Barbados to boost its exports to China. Pointing out that China has a popula- tion of $1.3 billion, with a significant in- terest in other cultures, Senior Officer with the Barbados Investment Development Corporation Paula Bourne highlighted that while there has been a marked increase in trade between Barbados and China since 2007, there was still significant potential for export growth from the island. She noted for example that products such as rum and sea island cotton could be marketed and sold to the People’s Republic of China as well as music and cultural items. “While we are small and we often think that we do not have a lot to offer, China attaches great importance to economic trade and cultural relations with Barbados and the wider Caribbean. There is significant business potential that can be developed between the two countries and we need to step out and ex- plore,” she stated. Bourne stressed that private sector companies must work with facilitators in order to get samples of their products into Chinese markets. Noting that there were 2.4 million mil- lionaires in China, she pointed out that by gaining the interest of a few of these in products and services of the Caribbean could make a significant difference. In addition, she suggested that in the same way that China had trade agree- ments with various countries across the world, it is time that it also had one in place with Caricom.