Listening Versus Skimming: What White Hip Hoppers at Vassar College Learn Or Overlook When They Listen to Rap Seth Tinkle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

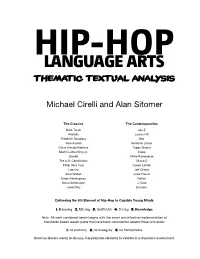

Language Arts Thematic Textual Analysis

HIP-HOPLANGUAGE ARTS THEMATIC TEXTUAL ANALYSIS Michael Cirelli and Alan Sitomer The Classics The Contemporaries Mark Twain Jay-Z Aristotle Lauryn Hill Frederick Douglass Nas Jane Austen Kendrick Lamar Oliver Wendell Holmes Tupac Shakur Martin Luther King Jr. Drake Gandhi Afrika Bambaataa The U.S. Constitution Chuck D Philip Vera Cruz Queen Latifah Lao-tzu Jeff Chang Alice Walker Lupe Fiasco Ernest Hemingway Rakim Sonia Sotomayor J. Cole Junot Díaz Eminem Delivering the 5th Element of Hip-Hop to Capable Young Minds 1. B-boying 2. MC-ing 3. Graffiti Art 4. DJ-ing 5. Knowledge Note: All work contained herein begins with the smart and effective implementation of standards-based lesson plans that have been constructed around three principles: 1. no profanity 2. no misogyny 3. no homophobia Great vocabulary words to discuss; inappropriate elements to validate in a classroom environment. HipHopLanguageArts3.indd 1 06/03/2015 15:38:37 2 | READ CLOSELY HIP-HOP INTERPRETATION GUIDE Question: Is violence ever an appropriate solution for resolving conflict? Consider the following text: from “Murder to Excellence” by Kanye West (with Jay-Z) I’m from the murder capital, where they murder for capital Heard about at least 3 killings this afternoon Lookin’ at the news like dang I was just with him after school, No shop class but half the school got a tool, And I could die any day type attitude Plus his little brother got shot reppin’ his avenue It’s time for us to stop and re-define black power 41 souls murdered in 50 hours 1. -

The Life & Rhymes of Jay-Z, an Historical Biography

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: THE LIFE & RHYMES OF JAY-Z, AN HISTORICAL BIOGRAPHY: 1969-2004 Omékongo Dibinga, Doctor of Philosophy, 2015 Dissertation directed by: Dr. Barbara Finkelstein, Professor Emerita, University of Maryland College of Education. Department of Teaching and Learning, Policy and Leadership. The purpose of this dissertation is to explore the life and ideas of Jay-Z. It is an effort to illuminate the ways in which he managed the vicissitudes of life as they were inscribed in the political, economic cultural, social contexts and message systems of the worlds which he inhabited: the social ideas of class struggle, the fact of black youth disempowerment, educational disenfranchisement, entrepreneurial possibility, and the struggle of families to buffer their children from the horrors of life on the streets. Jay-Z was born into a society in flux in 1969. By the time Jay-Z reached his 20s, he saw the art form he came to love at the age of 9—hip hop— become a vehicle for upward mobility and the acquisition of great wealth through the sale of multiplatinum albums, massive record deal signings, and the omnipresence of hip-hop culture on radio and television. In short, Jay-Z lived at a time where, if he could survive his turbulent environment, he could take advantage of new terrains of possibility. This dissertation seeks to shed light on the life and development of Jay-Z during a time of great challenge and change in America and beyond. THE LIFE & RHYMES OF JAY-Z, AN HISTORICAL BIOGRAPHY: 1969-2004 An historical biography: 1969-2004 by Omékongo Dibinga Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2015 Advisory Committee: Professor Barbara Finkelstein, Chair Professor Steve Klees Professor Robert Croninger Professor Derrick Alridge Professor Hoda Mahmoudi © Copyright by Omékongo Dibinga 2015 Acknowledgments I would first like to thank God for making life possible and bringing me to this point in my life. -

Mala Bizta Sochal Klu: Underground, Alternative and Commercial in Havana Hip Hop

Popular Music (2012) Volume 31/1. © Cambridge University Press 2012, pp. 1–24 doi:10.1017/S0261143011000432 Mala Bizta Sochal Klu: underground, alternative and commercial in Havana hip hop GEOFF BAKER Department of Music, Royal Holloway, University of London, Egham, Surrey TW20 0EX, UK E-mail: [email protected] Abstract The terms underground, alternative and commercial are widely used in discussions of popular music scenes in Havana and around the world. In Cuba, the words alternative and underground are often used interchangeably, in critical as well as popular discourse. I propose a working definition of, and a distinction between, these terms in Havana, since to render them synonymous reduces their usefulness. The distinction between underground and commercial, in contrast, is widely seen as self-evident, by critics as well as by fans. However, a simplistic dichotomy glosses over the interpe- netration of these terms, which are of limited use as analytical categories. This discussion of terminology is grounded in an analysis of the politics of style in Havana hip hop. Introduction [it’s] the dark side of Cuban music ...it’s neither Compay [Segundo], with the greatest respect, nor the conga drum for the tourists. ... (Underground rap-metal artist Jorge Rafael López on his alias, Mala Bizta Sochal Klu) We’re all underground here. In this country, everything’s underground. (Yrak Saenz of rap group Doble Filo) The trailer for the documentary Cuba Rebelión: Underground Music in Havana begins: ‘Since the nineties, an alternative music scene has come into existence in Cuba. An underground scene of young musicians who, despite their creative suppression and censorship, have the courage to make a statement.’ I examine the questions of suppression and censorship elsewhere (Baker 2011b); here I want to focus on the slip- page between the terms alternative and underground. -

Hip-Hop's Diversity and Misperceptions

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Honors College Summer 8-2020 Hip-Hop's Diversity and Misperceptions Andrew Cashman Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors Part of the Music Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HIP-HOP’S DIVERSITY AND MISPERCEPTIONS by Andrew Cashman A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for a Degree with Honors (Anthropology) The Honors College University of Maine August 2020 Advisory Committee: Joline Blais, Associate Professor of New Media, Advisor Kreg Ettenger, Associate Professor of Anthropology Christine Beitl, Associate Professor of Anthropology Sharon Tisher, Lecturer, School of Economics and Honors Stuart Marrs, Professor of Music 2020 Andrew Cashman All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT The misperception that hip-hop is a single entity that glorifies wealth and the selling of drugs, and promotes misogynistic attitudes towards women, as well as advocating gang violence is one that supports a mainstream perspective towards the marginalized.1 The prevalence of drug dealing and drug use is not a picture of inherent actions of members in the hip-hop community, but a reflection of economic opportunities that those in poverty see as a means towards living well. Some artists may glorify that, but other artists either decry it or offer it as a tragic reality. In hip-hop trends build off of music and music builds off of trends in a cyclical manner. -

“Rapper's Delight”

1 “Rapper’s Delight” From Genre-less to New Genre I was approached in ’77. A gentleman walked up to me and said, “We can put what you’re doing on a record.” I would have to admit that I was blind. I didn’t think that somebody else would want to hear a record re-recorded onto another record with talking on it. I didn’t think it would reach the masses like that. I didn’t see it. I knew of all the crews that had any sort of juice and power, or that was drawing crowds. So here it is two years later and I hear, “To the hip-hop, to the bang to the boogie,” and it’s not Bam, Herc, Breakout, AJ. Who is this?1 DJ Grandmaster Flash I did not think it was conceivable that there would be such thing as a hip-hop record. I could not see it. I’m like, record? Fuck, how you gon’ put hip-hop onto a record? ’Cause it was a whole gig, you know? How you gon’ put three hours on a record? Bam! They made “Rapper’s Delight.” And the ironic twist is not how long that record was, but how short it was. I’m thinking, “Man, they cut that shit down to fifteen minutes?” It was a miracle.2 MC Chuck D [“Rapper’s Delight”] is a disco record with rapping on it. So we could do that. We were trying to make a buck.3 Richard Taninbaum (percussion) As early as May of 1979, Billboard magazine noted the growing popularity of “rapping DJs” performing live for clubgoers at New York City’s black discos.4 But it was not until September of the same year that the trend gar- nered widespread attention, with the release of the Sugarhill Gang’s “Rapper’s Delight,” a fifteen-minute track powered by humorous party rhymes and a relentlessly funky bass line that took the country by storm and introduced a national audience to rap. -

UNDERSTANDING PORTRAYALS of LAW ENFORCEMENT OFFICERS in HIP-HOP LYRICS SINCE 2009 By

ON THE BEAT: UNDERSTANDING PORTRAYALS OF LAW ENFORCEMENT OFFICERS IN HIP-HOP LYRICS SINCE 2009 by Francesca A. Keesee A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of George Mason University in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degrees of Master of Science Conflict Analysis and Resolution Master of Arts Conflict Resolution and Mediterranean Security Committee: ___________________________________________ Chair of Committee ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ Graduate Program Director ___________________________________________ Dean, School for Conflict Analysis and Resolution Date: _____________________________________ Fall Semester 2017 George Mason University Fairfax, VA University of Malta Valletta, Malta On the Beat: Understanding Portrayals of Law Enforcement Officers in Hip-hop Lyrics Since 2009 A Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degrees of Master of Science at George Mason University and Master of Arts at the University of Malta by Francesca A. Keesee Bachelor of Arts University of Virginia, 2015 Director: Juliette Shedd, Professor School for Conflict Analysis and Resolution Fall Semester 2017 George Mason University Fairfax, Virginia University of Malta Valletta, Malta Copyright 2016 Francesca A. Keesee All Rights Reserved ii DEDICATION This is dedicated to all victims of police brutality. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am forever grateful to my best friend, partner in crime, and husband, Patrick. -

Raja Mohan 21M.775 Prof. Defrantz from Bronx's Hip-Hop To

Raja Mohan 21M.775 Prof. DeFrantz From Bronx’s Hip-Hop to Bristol’s Trip-Hop As Tricia Rose describes, the birth of hip-hop occurred in Bronx, a marginalized city, characterized by poverty and congestion, serving as a backdrop for an art form that flourished into an international phenomenon. The city inhabited a black culture suffering from post-war economic effects and was cordoned off from other regions of New York City due to modifications in the highway system, making the people victims of “urban renewal.” (30) Given the opportunity to form new identities in the realm of hip-hop and share their personal accounts and ideologies, similar to traditions in African oral history, these people conceived a movement whose worldwide appeal impacted major events such as the Million Man March. Hip-hop’s enormous influence on the world is undeniable. In the isolated city of Bristol located in England arose a style of music dubbed trip-hop. The origins of trip-hop clearly trace to hip-hop, probably explaining why artists categorized in this genre vehemently oppose to calling their music trip-hop. They argue their music is hip-hop, or perhaps a fresh and original offshoot of hip-hop. Mushroom, a member of the trip-hop band Massive Attack, said, "We called it lover's hip hop. Forget all that trip hop bullshit. There's no difference between what Puffy or Mary J Blige or Common Sense is doing now and what we were doing…” (Bristol Underground Website) Trip-hop can abstractly be defined as music employing hip-hop, soul, dub grooves, jazz samples, and break beat rhythms. -

Understanding the White, Mainstream Appeal of Hip-Hop Music

UNDERSTANDING THE WHITE, MAINSTREAM APPEAL OF HIP-HOP MUSIC: IS IT A FAD OR IS IT THE REAL THING? by JANISE MARIE BLACKSHEAR (Under the Direction of Tina M. Harris) ABSTRACT This study explores why young, White, suburban adults are consumers and fans of hip- hop music, considering it is a Black cultural art form that is specific to African-Americans. While the hip-hop music industry is predominately Black, studies consistently show that over 70% of its consumers are White. Through focus group data, this thesis revealed that hip-hop music is used by White listeners as a means for negotiating social group memberships (i.e. race, class). More importantly, the findings also contribute to the more public debate and dialogue that has plagued Black music, offering further evidence that White appropriation of Black cultural artifacts (e.g., jazz music) remains a constant, particularly in the case of hip-hop. While the findings are not generalizable to all young White suburban consumers of this genre of music, it may be inferred that a White racial identity does not help this group of consumers relate to hip- hop music. INDEX WORDS: Hip-hop Music, Whiteness, Rap Communication Messages, Racial Identity Performance, In-group/Out-group Membership UNDERSTANDING THE WHITE, MAINSTREAM APPEAL OF HIP-HOP MUSIC: IS IT A FAD OR IS IT THE REAL THING? by JANISE MARIE BLACKSHEAR B.A., Central Michigan University, 2005 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2007 © 2007 Janise Marie Blackshear All Rights Reserved UNDERSTANDING THE WHITE, MAINSTREAM APPEAL OF HIP-HOP MUSIC: IS IT A FAD OR IS IT THE REAL THING? by JANISE MARIE BLACKSHEAR Major Professor: Tina M. -

Spiritualizing Hip Hop with I.C.E.: the Poetic Spiritual

SPIRITUALIZING HIP HOP WITH I.C.E.: THE POETIC SPIRITUAL NARRATIVES OF FOUR BLACK EDUCATIONAL LEADERS FROM HIP HOP COMMUNITIES by Alexis C. Maston A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Council of Texas State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy with a Major in Adult, Professional, and Community Education May 2014 Committee Members: Jovita Ross-Gordon, Co-Chair John Oliver, Co-Chair Ann K. Brooks Raphael Travis, Jr. COPYRIGHT by Alexis C. Maston 2014 FAIR USE AND AUTHOR’S PERMISSION STATEMENT Fair Use This work is protected by the Copyright Laws of the United States (Public Law 94-553, section 107). Consistent with fair use as defined in the Copyright Laws, brief quotations from this material are allowed with proper acknowledgement. Use of this material for financial gain without the author’s express written permission is not allowed. Duplication Permission As the copyright holder of this work I, Alexis C. Maston, authorize duplication of this work, in whole or in part, for educational or scholarly purposes only. DEDICATION This dissertation is first dedicated to my Lord and personal savior Jesus without whom this study would not have been possible. You are Alpha, Omega, the beginning and the end, and I went on this journey because you directed me to. Secondly, I dedicate this to my paternal and maternal grandparents, Fred and Emma Jean Maston, and Jacqueline Perkins, what you did years ago in your own lives made it possible for me to obtain this great opportunity. Thirdly, this dissertation is dedicated to Hip Hop communities worldwide who have always carried the essence of spirituality; this dissertation will uncover some of that truth. -

Hip-Hop & the Global Imprint of a Black Cultural Form

Hip-Hop & the Global Imprint of a Black Cultural Form Marcyliena Morgan & Dionne Bennett To me, hip-hop says, “Come as you are.” We are a family. Hip-hop is the voice of this generation. It has become a powerful force. Hip-hop binds all of these people, all of these nationalities, all over the world together. Hip-hop is a family so everybody has got to pitch in. East, west, north or south–we come MARCYLIENA MORGAN is from one coast and that coast was Africa. Professor of African and African –dj Kool Herc American Studies at Harvard Uni- versity. Her publications include Through hip-hop, we are trying to ½nd out who we Language, Discourse and Power in are, what we are. That’s what black people in Amer- African American Culture (2002), ica did. The Real Hiphop: Battling for Knowl- –mc Yan1 edge, Power, and Respect in the LA Underground (2009), and “Hip- hop and Race: Blackness, Lan- It is nearly impossible to travel the world without guage, and Creativity” (with encountering instances of hip-hop music and cul- Dawn-Elissa Fischer), in Doing Race: 21 Essays for the 21st Century ture. Hip-hop is the distinctive graf½ti lettering (ed. Hazel Rose Markus and styles that have materialized on walls worldwide. Paula M.L. Moya, 2010). It is the latest dance moves that young people per- form on streets and dirt roads. It is the bass beats DIONNE BENNETT is an Assis- mc tant Professor of African Ameri- and styles of dress at dance clubs. It is local s can Studies at Loyola Marymount on microphones with hands raised and moving to University. -

Hip-Hop and African American Culture

The Power of the Underground: Hip-Hop and African American Culture James Braxton PETERSON Over the last 40 years hip-hop culture has developed from a relatively unknown and largely ignored inner city culture into a global phenomenon. The foundational elements of hip-hop culture (DJ-ing, MC-ing, Breakdance, and Graffiti/Graf)are manifest in youth culture across the globe, including Japan, France, Germany, Ghana, Cuba, India and the UK. Considering its humble beginnings in the South and West Bronx neighborhoods of New York City, the global development of hip-hop is an amazing cultural phenomenon. 1) Moreover, Hip Hop’s current global popularity might obscure the fact of its humble underground beginnings. We do not generally think of hip-hop culture as being an underground phenomenon in the 21st century, mostly because of the presence of rap music and other elements of the culture in marketing, in advertising and in popular culture all over the world. But hip-hop culture emerges from a variety of undergrounds, undergrounds that can be defined in many ways. Consider the New York subway system, the illegal nature of graffiti art, or the musical “digging” required to produce hip-hop tracks and you can begin to grasp the literal and metaphorical ways that hip-hop culture is informed via the aesthetics of the underground. The underground nature of hip-hop culture beings with its origins in the mid-1970s in New York City. In 1967, Clive Campbell, also known as the legendary DJ Kool Herc, immigrated to New York City and settled in the West Bronx. -

Mike Epps Slated As Host for This Year's BET HIP HOP AWARDS

Mike Epps Slated As Host For This Year's BET HIP HOP AWARDS G.O.O.D. MUSIC'S KANYE WEST LEADS WITH 17 IMPRESSIVE NOMINATIONS; 2CHAINZ FOLLOWS WITH 13 AND DRAKE ROUNDS THINGS OUT WITH 11 NODS SIX CYPHERS TO BE INCLUDED IN THIS YEAR'S AWARDS TAPING AT THE BOISFEUILLET JONES ATLANTA CIVIC CENTER IN ATLANTA ON SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 29, 2012; NETWORK PREMIERE ON TUESDAY, OCTOBER 9, 2012 AT 8:00 PM* NEW YORK, Sept. 12, 2012 /PRNewswire/ -- BET Networks' flagship music variety program, "106 & PARK," officially announced the nominees for the BET HIP HOP AWARDS (#HIPHOPAWARDS). Actor and comedian Mike Epps (@THEREALMIKEEPPS) will once again host this year's festivities from the Boisfeuillet Jones Atlanta Civic Center in Atlanta on Saturday, September 29, 2012 with the network premiere on Tuesday, October 9, 2012 at 8:00 pm*. Mike Epps completely took-over "106 & PARK" today to mark the special occasion and revealed some of the notable nominees with help from A$AP Rocky, Ca$h Out, DJ Envy and DJ Drama. Hip Hop Awards nominated artists A$AP Rocky and Ca$h Out performed their hits "Goldie" and "Cashin Out" while nominated deejay's DJ Envy and DJ Drama spun for the crowd. The BET HIP HOP AWARDS Voting Academy is comprised of a select assembly of music and entertainment executives, media and industry influencers. Celebrating the biggest names in the game, newcomers on the scene, and shining a light on the community, the BET HIP HOP AWARDS is ready to salute the very best in hip hop culture.