Spiritualizing Hip Hop with I.C.E.: the Poetic Spiritual

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Language Arts Thematic Textual Analysis

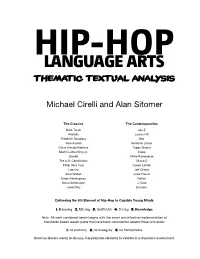

HIP-HOPLANGUAGE ARTS THEMATIC TEXTUAL ANALYSIS Michael Cirelli and Alan Sitomer The Classics The Contemporaries Mark Twain Jay-Z Aristotle Lauryn Hill Frederick Douglass Nas Jane Austen Kendrick Lamar Oliver Wendell Holmes Tupac Shakur Martin Luther King Jr. Drake Gandhi Afrika Bambaataa The U.S. Constitution Chuck D Philip Vera Cruz Queen Latifah Lao-tzu Jeff Chang Alice Walker Lupe Fiasco Ernest Hemingway Rakim Sonia Sotomayor J. Cole Junot Díaz Eminem Delivering the 5th Element of Hip-Hop to Capable Young Minds 1. B-boying 2. MC-ing 3. Graffiti Art 4. DJ-ing 5. Knowledge Note: All work contained herein begins with the smart and effective implementation of standards-based lesson plans that have been constructed around three principles: 1. no profanity 2. no misogyny 3. no homophobia Great vocabulary words to discuss; inappropriate elements to validate in a classroom environment. HipHopLanguageArts3.indd 1 06/03/2015 15:38:37 2 | READ CLOSELY HIP-HOP INTERPRETATION GUIDE Question: Is violence ever an appropriate solution for resolving conflict? Consider the following text: from “Murder to Excellence” by Kanye West (with Jay-Z) I’m from the murder capital, where they murder for capital Heard about at least 3 killings this afternoon Lookin’ at the news like dang I was just with him after school, No shop class but half the school got a tool, And I could die any day type attitude Plus his little brother got shot reppin’ his avenue It’s time for us to stop and re-define black power 41 souls murdered in 50 hours 1. -

The Dark Unknown History

Ds 2014:8 The Dark Unknown History White Paper on Abuses and Rights Violations Against Roma in the 20th Century Ds 2014:8 The Dark Unknown History White Paper on Abuses and Rights Violations Against Roma in the 20th Century 2 Swedish Government Official Reports (SOU) and Ministry Publications Series (Ds) can be purchased from Fritzes' customer service. Fritzes Offentliga Publikationer are responsible for distributing copies of Swedish Government Official Reports (SOU) and Ministry publications series (Ds) for referral purposes when commissioned to do so by the Government Offices' Office for Administrative Affairs. Address for orders: Fritzes customer service 106 47 Stockholm Fax orders to: +46 (0)8-598 191 91 Order by phone: +46 (0)8-598 191 90 Email: [email protected] Internet: www.fritzes.se Svara på remiss – hur och varför. [Respond to a proposal referred for consideration – how and why.] Prime Minister's Office (SB PM 2003:2, revised 02/05/2009) – A small booklet that makes it easier for those who have to respond to a proposal referred for consideration. The booklet is free and can be downloaded or ordered from http://www.regeringen.se/ (only available in Swedish) Cover: Blomquist Annonsbyrå AB. Printed by Elanders Sverige AB Stockholm 2015 ISBN 978-91-38-24266-7 ISSN 0284-6012 3 Preface In March 2014, the then Minister for Integration Erik Ullenhag presented a White Paper entitled ‘The Dark Unknown History’. It describes an important part of Swedish history that had previously been little known. The White Paper has been very well received. Both Roma people and the majority population have shown great interest in it, as have public bodies, central government agencies and local authorities. -

RB010: Year of the Survey

EU-SILC Description Target Variables Personal Register (R-file) RB010: Year of the survey BASIC DATA (Basic personal data) Cross-sectional and longitudinal Reference period: current Unit: all current household members (of any age) and former household members Mode of collection: interviewer Values year (4 digits) 2011 Operation - 1 - EU-SILC Description Target Variables Personal Register (R-file) RB020: Country BASIC DATA (Basic personal data) Cross-sectional and longitudinal Reference period: constant Unit: all current household members (of any age) and former household members Mode of collection: frame Values BE Belgique/Belgïe BG Bulgaria CZ Czech republic DK Denmark DE Deutschland EE Estonia IE Ireland GR Elláda ES España FR France IT Italia CY Cyprus LV Latvia LT Lithuania LU Luxembourg HU Hungary MT Malta NL Nederland AT Österreich PL Poland PT Portugal RO Romania SI Slovenia SK Slovak republic FI Suomi SE Sverige UK United Kingdom CH Switzerland HR Croatia IS Iceland NO Norway TR Turkey 2011 Operation - 2 - EU-SILC Description Target Variables Personal Register (R-file) RB030: Personal ID BASIC DATA (Basic personal data) Cross-sectional and longitudinal Reference period: constant Unit: all current household members (of any age) and former household members Mode of collection: frame, register or interviewer Values (cross-sectional) ID number see construction in chapter 'General description' RB031: Year of immigration BASIC DATA (Basic personal data) Cross-sectional and longitudinal Reference period: constant Unit: all current household members (of any age) and former household members Mode of collection: frame, register or interviewer Values 1890-year of the survey Note: If the person immigrated before 1890 the variable will be filled in with the value 1890. -

The Life & Rhymes of Jay-Z, an Historical Biography

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: THE LIFE & RHYMES OF JAY-Z, AN HISTORICAL BIOGRAPHY: 1969-2004 Omékongo Dibinga, Doctor of Philosophy, 2015 Dissertation directed by: Dr. Barbara Finkelstein, Professor Emerita, University of Maryland College of Education. Department of Teaching and Learning, Policy and Leadership. The purpose of this dissertation is to explore the life and ideas of Jay-Z. It is an effort to illuminate the ways in which he managed the vicissitudes of life as they were inscribed in the political, economic cultural, social contexts and message systems of the worlds which he inhabited: the social ideas of class struggle, the fact of black youth disempowerment, educational disenfranchisement, entrepreneurial possibility, and the struggle of families to buffer their children from the horrors of life on the streets. Jay-Z was born into a society in flux in 1969. By the time Jay-Z reached his 20s, he saw the art form he came to love at the age of 9—hip hop— become a vehicle for upward mobility and the acquisition of great wealth through the sale of multiplatinum albums, massive record deal signings, and the omnipresence of hip-hop culture on radio and television. In short, Jay-Z lived at a time where, if he could survive his turbulent environment, he could take advantage of new terrains of possibility. This dissertation seeks to shed light on the life and development of Jay-Z during a time of great challenge and change in America and beyond. THE LIFE & RHYMES OF JAY-Z, AN HISTORICAL BIOGRAPHY: 1969-2004 An historical biography: 1969-2004 by Omékongo Dibinga Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2015 Advisory Committee: Professor Barbara Finkelstein, Chair Professor Steve Klees Professor Robert Croninger Professor Derrick Alridge Professor Hoda Mahmoudi © Copyright by Omékongo Dibinga 2015 Acknowledgments I would first like to thank God for making life possible and bringing me to this point in my life. -

UNDERSTANDING PORTRAYALS of LAW ENFORCEMENT OFFICERS in HIP-HOP LYRICS SINCE 2009 By

ON THE BEAT: UNDERSTANDING PORTRAYALS OF LAW ENFORCEMENT OFFICERS IN HIP-HOP LYRICS SINCE 2009 by Francesca A. Keesee A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of George Mason University in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degrees of Master of Science Conflict Analysis and Resolution Master of Arts Conflict Resolution and Mediterranean Security Committee: ___________________________________________ Chair of Committee ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ Graduate Program Director ___________________________________________ Dean, School for Conflict Analysis and Resolution Date: _____________________________________ Fall Semester 2017 George Mason University Fairfax, VA University of Malta Valletta, Malta On the Beat: Understanding Portrayals of Law Enforcement Officers in Hip-hop Lyrics Since 2009 A Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degrees of Master of Science at George Mason University and Master of Arts at the University of Malta by Francesca A. Keesee Bachelor of Arts University of Virginia, 2015 Director: Juliette Shedd, Professor School for Conflict Analysis and Resolution Fall Semester 2017 George Mason University Fairfax, Virginia University of Malta Valletta, Malta Copyright 2016 Francesca A. Keesee All Rights Reserved ii DEDICATION This is dedicated to all victims of police brutality. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am forever grateful to my best friend, partner in crime, and husband, Patrick. -

A Stylistic Analysis of 2Pac Shakur's Rap Lyrics: in the Perpspective of Paul Grice's Theory of Implicature

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Theses Digitization Project John M. Pfau Library 2002 A stylistic analysis of 2pac Shakur's rap lyrics: In the perpspective of Paul Grice's theory of implicature Christopher Darnell Campbell Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project Part of the Rhetoric Commons Recommended Citation Campbell, Christopher Darnell, "A stylistic analysis of 2pac Shakur's rap lyrics: In the perpspective of Paul Grice's theory of implicature" (2002). Theses Digitization Project. 2130. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/2130 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the John M. Pfau Library at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses Digitization Project by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A STYLISTIC ANALYSIS OF 2PAC SHAKUR'S RAP LYRICS: IN THE PERSPECTIVE OF PAUL GRICE'S THEORY OF IMPLICATURE A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in English: English Composition by Christopher Darnell Campbell September 2002 A STYLISTIC ANALYSIS OF 2PAC SHAKUR'S RAP LYRICS: IN THE PERSPECTIVE OF PAUL GRICE'S THEORY OF IMPLICATURE A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Christopher Darnell Campbell September 2002 Approved.by: 7=12 Date Bruce Golden, English ABSTRACT 2pac Shakur (a.k.a Makaveli) was a prolific rapper, poet, revolutionary, and thug. His lyrics were bold, unconventional, truthful, controversial, metaphorical and vulgar. -

Extensions of Remarks. Hon. Donald M. Fraser

February 19, 1969 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS 4031 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS. AID FOR BIAFRAN CHILDREN be known as the "Ravensbrueck Lapins" tions. On the basis of his first-hand obser was of a dual nature. One aspect was to bring vations, Mr. Cohen spoke of growing problems them to the United States for medical and confronting evacuation of children by air. HON. DONALD M. FRASER surgical care. The other aspect was to obtain He brought U3 together with Mr. G. A. On Oi' MINNESOTA from the German government at Bonn ade yegbula, Permanent Secretary of Biafra, who quate compensation that would enable them had just arrived in New York on a brief gov IN THE HOUSE OP REPRESENTATIVES to live Without continued and excessive hard ernment mission. Mr. Onyegbula spoke of the Tuesday, February 18, 1969 ship. Both these parts of the project were severity of Biafra's needs. Two thousand carried out. children and 4,000 adults were dying daily Mr. FRASER. Mr. Speaker, one of the The editors now invite the readers of SR of starvation. Food and medical supplies most remarkable humanitarian efforts to join them in a fourth project. It is called were being flown into Bia.fra In larger quan directed at relieving the misery of the ABc-Aid for Biafran Children. HereWith, tities than had been possible for some Nigerian-Biafran tragedy is known as some background. months. But the situation continued to be Aid for Biafran Children-ABC. Last September, when the food blockade of critical and was apt to remain that way Biafra was at its worst, and when thousands until there was a dramatic breakthrough in One of the principals in this effort is of children were dying from protein shortage, direct access. -

Hip Hop Feminism Comes of Age.” I Am Grateful This Is the First 2020 Issue JHHS Is Publishing

Halliday and Payne: Twenty-First Century B.I.T.C.H. Frameworks: Hip Hop Feminism Come Published by VCU Scholars Compass, 2020 1 Journal of Hip Hop Studies, Vol. 7, Iss. 1 [2020], Art. 1 Editor in Chief: Travis Harris Managing Editor Shanté Paradigm Smalls, St. John’s University Associate Editors: Lakeyta Bonnette-Bailey, Georgia State University Cassandra Chaney, Louisiana State University Willie "Pops" Hudson, Azusa Pacific University Javon Johnson, University of Nevada, Las Vegas Elliot Powell, University of Minnesota Books and Media Editor Marcus J. Smalls, Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM) Conference and Academic Hip Hop Editor Ashley N. Payne, Missouri State University Poetry Editor Jeffrey Coleman, St. Mary's College of Maryland Global Editor Sameena Eidoo, Independent Scholar Copy Editor: Sabine Kim, The University of Mainz Reviewer Board: Edmund Adjapong, Seton Hall University Janee Burkhalter, Saint Joseph's University Rosalyn Davis, Indiana University Kokomo Piper Carter, Arts and Culture Organizer and Hip Hop Activist Todd Craig, Medgar Evers College Aisha Durham, University of South Florida Regina Duthely, University of Puget Sound Leah Gaines, San Jose State University Journal of Hip Hop Studies 2 https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/jhhs/vol7/iss1/1 2 Halliday and Payne: Twenty-First Century B.I.T.C.H. Frameworks: Hip Hop Feminism Come Elizabeth Gillman, Florida State University Kyra Guant, University at Albany Tasha Iglesias, University of California, Riverside Andre Johnson, University of Memphis David J. Leonard, Washington State University Heidi R. Lewis, Colorado College Kyle Mays, University of California, Los Angeles Anthony Nocella II, Salt Lake Community College Mich Nyawalo, Shawnee State University RaShelle R. -

New Waves in Aesthetics

New Waves in Aesthetics Edited by Kathleen Stock and Katherine Thomson-Jones New Waves in Aesthetics June 21, 2008 10:20 MAC/NWA Page-i 9780230_220478_01_prexx New Waves in Philosophy Series Editors: Vincent F. Hendricks and Duncan Pritchard Titles include: Jan Kyrre Berg Olsen, Evan Selinger and Søren Riis (editors) NEW WAVES IN PHILOSOPHY OF TECHNOLOGY Vincent F. Hendricks and Duncan Pritchard (editors) NEW WAVES IN EPISTEMOLOGY Thomas S. Petersen, Jesper Ryberg and Clark Wolf (editors) NEW WAVES IN APPLIED ETHICS Kathleen Stock and Katherine Thomson-Jones (editors) NEW WAVES IN AESTHETICS Forthcoming: Yujin Nagasawa and Erik Wielenberg (editors) NEW WAVES IN PHILOSOPHY OF RELIGION Boudewijn DeBruin and Christopher Zurn (editors) NEW WAVES IN POLITICAL PHILOSOPHY Future Volumes New Waves in Philosophy of Science New Waves in Philosophy of Language New Waves in Philosophy of Mathematics New Waves in Philosophy of Mind New Waves in Meta-Ethics New Waves in Ethics New Waves in Metaphysics New Waves in Formal Philosophy New Waves in Philosophy of Law New Waves in Philosophy Series Standing Order ISBN 978–0–230–53797–2 (hardcover) Series Standing Order ISBN 978–0–230–53798–9 (paperback) (outside North America only) You can receive future titles in this series as they are published by placing a standing order. Please contact your bookseller or, in case of difficulty, write to us at the address below with your name and address, the title of the series and the ISBN quoted above. Customer Services Department, Macmillan Distribution Ltd, Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS, England June 21, 2008 10:20 MAC/NWA Page-ii 9780230_220478_01_prexx New Waves in Aesthetics Edited by Kathleen Stock and Katherine Thomson-Jones June 21, 2008 10:20 MAC/NWA Page-iii 9780230_220478_01_prexx Selection and editorial matter © Kathleen Stock and Katherine Thomson-Jones 2008 Chapters © the individual authors All rights reserved. -

The Evolution of Commercial Rap Music Maurice L

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2011 A Historical Analysis: The Evolution of Commercial Rap Music Maurice L. Johnson II Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF COMMUNICATION A HISTORICAL ANALYSIS: THE EVOLUTION OF COMMERCIAL RAP MUSIC By MAURICE L. JOHNSON II A Thesis submitted to the Department of Communication in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Degree Awarded: Summer Semester 2011 The members of the committee approve the thesis of Maurice L. Johnson II, defended on April 7, 2011. _____________________________ Jonathan Adams Thesis Committee Chair _____________________________ Gary Heald Committee Member _____________________________ Stephen McDowell Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members. ii I dedicated this to the collective loving memory of Marlena Curry-Gatewood, Dr. Milton Howard Johnson and Rashad Kendrick Williams. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my sincere gratitude to the individuals, both in the physical and the spiritual realms, whom have assisted and encouraged me in the completion of my thesis. During the process, I faced numerous challenges from the narrowing of content and focus on the subject at hand, to seemingly unjust legal and administrative circumstances. Dr. Jonathan Adams, whose gracious support, interest, and tutelage, and knowledge in the fields of both music and communications studies, are greatly appreciated. Dr. Gary Heald encouraged me to complete my thesis as the foundation for future doctoral studies, and dissertation research. -

Abstract Music Is an Essential Part of Our Lives. the World Wouldn't Be The

Abstract Music is an essential part of our lives. The world wouldn’t be the same without it. Everyone is so enthralled by music that whether they are bored or they are working, music is often times the thing that they want to have playing in the background of their life. A. The wide range of genres allows people to choose the type of music they want to listen to. The music can range from soothing and light forms to the heavy metal instrumentals and vocals. Many singers and artists are working in the music industry, and many of them have served a lot to this industry. Best sellers of the artists are appreciated in the whole world. It is known know, music knows no boundaries are when a singer does a fantastic job; they become famous all across the globe. Sadly, as time goes on musicians pass away however, their legacy remains very much alive have passed, but their names are still alive. The world still listens to their music and appreciates their work. One such singer is Michael Jackson. His album Thriller broke the records and was the best seller. No one can be neat the files of the king of pop. Similarly, Pink Floyd made records by their album The Dark Side of the Moon. It was an enormous economic and critical success. Many teens are still obsessed by the songs of Pink Floyd. AC/DC gave an album called Back in Black. This was also one of the major hits of that era. All these records are still alive. -

Janet Clemens: Imagine Being Considered for a Huge Commission, with Your Qualifications Being Debated on the Senate Floor

>> Janet Clemens: Imagine being considered for a huge commission, with your qualifications being debated on the Senate floor. Your age, your experience, your talent are all being questioned. Now imagine your place is restricted to the balcony, observing silently while surrounded by press. [ Music ] You're listening to Shaping History: Women in Capitol Art, produced by the Capitol Visitor Center. Our mission is to inform, involve, and inspire every visitor to the United States Capitol. I'm your host, Janet Clemens. [ Music ] There are multiple ways that statues are incorporated into the Capitol collection. In addition to the National Statuary Hall Collection, Congress can receive artworks as gifts, or they can commission specific works. Vinnie Ream was the first woman to receive one of these commissions, in 1866, and also has two statues in the National Statuary Hall Collection, making her the only woman to have three sculptures in the Capitol collection. While there were other women who forged paths in sculpture, Vinnie Ream stands apart. Inexperienced, ambitious, strategic, bewitching, an untutored genius, undoubtedly as gifted as she was attractive, a woman illustrious only in mind, not just famous, but notorious, these are a few of the phrases that were used to describe Vinnie Ream during her career. I spoke to Melissa Dabakis, Professor of Art History Emerita at Kenyon College, about this young celebrity sculptor. She's the author of a book, "A Sisterhood of Sculptors: American Artists in Nineteenth-Century Rome." Professor Dabakis, welcome to the podcast. >> Melissa Dabakis: Thank you. >> Janet Clemens: So we're going to talk today about Vinnie Ream.