Part I. Democracy in Uganda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UGANDA COUNTRY REPORT October 2004 Country

UGANDA COUNTRY REPORT October 2004 Country Information & Policy Unit IMMIGRATION & NATIONALITY DIRECTORATE HOME OFFICE, UNITED KINGDOM Uganda Report - October 2004 CONTENTS 1. Scope of the Document 1.1 - 1.10 2. Geography 2.1 - 2.2 3. Economy 3.1 - 3.3 4. History 4.1 – 4.2 • Elections 1989 4.3 • Elections 1996 4.4 • Elections 2001 4.5 5. State Structures Constitution 5.1 – 5.13 • Citizenship and Nationality 5.14 – 5.15 Political System 5.16– 5.42 • Next Elections 5.43 – 5.45 • Reform Agenda 5.46 – 5.50 Judiciary 5.55 • Treason 5.56 – 5.58 Legal Rights/Detention 5.59 – 5.61 • Death Penalty 5.62 – 5.65 • Torture 5.66 – 5.75 Internal Security 5.76 – 5.78 • Security Forces 5.79 – 5.81 Prisons and Prison Conditions 5.82 – 5.87 Military Service 5.88 – 5.90 • LRA Rebels Join the Military 5.91 – 5.101 Medical Services 5.102 – 5.106 • HIV/AIDS 5.107 – 5.113 • Mental Illness 5.114 – 5.115 • People with Disabilities 5.116 – 5.118 5.119 – 5.121 Educational System 6. Human Rights 6.A Human Rights Issues Overview 6.1 - 6.08 • Amnesties 6.09 – 6.14 Freedom of Speech and the Media 6.15 – 6.20 • Journalists 6.21 – 6.24 Uganda Report - October 2004 Freedom of Religion 6.25 – 6.26 • Religious Groups 6.27 – 6.32 Freedom of Assembly and Association 6.33 – 6.34 Employment Rights 6.35 – 6.40 People Trafficking 6.41 – 6.42 Freedom of Movement 6.43 – 6.48 6.B Human Rights Specific Groups Ethnic Groups 6.49 – 6.53 • Acholi 6.54 – 6.57 • Karamojong 6.58 – 6.61 Women 6.62 – 6.66 Children 6.67 – 6.77 • Child care Arrangements 6.78 • Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) -

An Independent Review of the Performance of Special Interest Groups in Parliament

DEEPENING DEMOCRACY AND ENHANCING SUSTAINABLE LIVELIHOODS IN UGANDA DEEPENING DEMOCRACY AND ENHANCING SUSTAINABLE LIVELIHOODS IN UGANDA An Independent Review of the Performance of Special Interest Groups in Parliament Arthur Bainomugisha Elijah D. Mushemeza ACODE Policy Research Series, No. 13, 2006 i DEEPENING DEMOCRACY AND ENHANCING SUSTAINABLE LIVELIHOODS IN UGANDA DEEPENING DEMOCRACY AND ENHANCING SUSTAINABLE LIVELIHOODS IN UGANDA An Independent Review of the Performance of Special Interest Groups in Parliament Arthur Bainomugisha Elijah D. Mushemeza ACODE Policy Research Series, No. 13, 2006 ii DEEPENING DEMOCRACY AND ENHANCING SUSTAINABLE LIVELIHOODS IN UGANDA TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ACRONYMS................................................................ iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS............................................................ iv EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.............................................................. v 1.0. INTRODUCTION............................................................. 1 2.0. BACKGROUND: CONSTITUTIONAL AND POLITICAL HISTORY OF UGANDA.......................................................... 2 3.0. RESEARCH METHODOLOGY................................................... 3 4.0. LEGISLATIVE REPRESENTATION AND ENVIRONMENTAL GOVERNANCE.................................................................... 3 5.0. UNDERSTANDING THE CONCEPTS OF AFFIRMATIVE ACTION AND REPRESENTATION.................................................. 5 5.1. Representative Democracy in a Historical Perspective............................................................. -

Collapse, War and Reconstruction in Uganda

Working Paper No. 27 - Development as State-Making - COLLAPSE, WAR AND RECONSTRUCTION IN UGANDA AN ANALYTICAL NARRATIVE ON STATE-MAKING Frederick Golooba-Mutebi Makerere Institute of Social Research Makerere University January 2008 Copyright © F. Golooba-Mutebi 2008 Although every effort is made to ensure the accuracy and reliability of material published in this Working Paper, the Crisis States Research Centre and LSE accept no responsibility for the veracity of claims or accuracy of information provided by contributors. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission in writing of the publisher nor be issued to the public or circulated in any form other than that in which it is published. Requests for permission to reproduce this Working Paper, of any part thereof, should be sent to: The Editor, Crisis States Research Centre, DESTIN, LSE, Houghton Street, London WC2A 2AE. Crisis States Working Papers Series No.2 ISSN 1749-1797 (print) ISSN 1749-1800 (online) 1 Crisis States Research Centre Collapse, war and reconstruction in Uganda An analytical narrative on state-making Frederick Golooba-Mutebi∗ Makerere Institute of Social Research Abstract Since independence from British colonial rule, Uganda has had a turbulent political history characterised by putsches, dictatorship, contested electoral outcomes, civil wars and a military invasion. There were eight changes of government within a period of twenty-four years (from 1962-1986), five of which were violent and unconstitutional. This paper identifies factors that account for these recurrent episodes of political violence and state collapse. -

Climate Change Actors' Landscape of Uganda

R Reform of the Urban Water and Sanitation Sector Programme nnnnn nn(RUWASS) M Climate Change Actors’ Landscape of Uganda; Sept.2010 GTZ -The German Technical Cooperation Is an international cooperation enterprise for sustainable development with worldwide operations, the federally owned Deutsche Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit (GTZ) GmbH supports the German Government in achieving its development-policy objectives. It provides viable, forward-looking solutions for political, economic, ecological and social development in a globalised world. Working under difficult conditions, GTZ promotes complex reforms and change processes. Its corporate objective is to improve people’s living conditions on a sustainable basis. GTZ-Reform of Urban Water And Sanitation Sector (RUWASS) GTZ on behalf of the German Federal Ministry of Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) supports the Government of Uganda (GoU) in implementing its reforms of the urban water sector through the RUWASS programme which involves strengthening the institutional, regulatory and business competences of the partner institutions, and raising their efficiency. Contact details GTZ - RUWASS Plot 83 Luthuli Avenue, Bugolobi PO Box 10346 Kampala, Uganda Tel: (+256) 312 26 30 69/70 http://www.ruwas.co.ug http://www.gtz.de Main author Camilla Preller Consultant GTZ-RUWASS [email protected] Contributing authors Daniel Opwonya (Chapter 1, Chapter 3 and Document review) Technical Advisor GTZ-RUWASS [email protected] [email protected] Maarten Van der Ploeg (Document review) Technical Advisor GTZ-RUWASS [email protected] [email protected] Copyright © GTZ-RUWASS, 2010. ii Climate Change Actors’ Landscape of Uganda; Sept.2010 “It is critical that the coordination of adaptation is done from centres of power in the national government. -

Africa Confidential

www.africa-confidential.com 23 November 2001 Vol 42 No 23 AFRICA CONFIDENTIAL TANZANIA 2 SOMALIA Mkapa winds it up By meeting most of the opposition Moving target Civic United Front’s demands for A state in turmoil offers no safe haven for terrorists fleeing the electoral reform in Zanzibar, onslaught in Afghanistan President Mkapa seems to have won an end to the political stand- If Usama bin Laden and his comrades headed for Somalia, they could find it even less comfortable than off on the islands. Now attention Afghanistan. American and French ships patrol the coastline and blockade some ports. There are turns to the race to choose his reports of German troops joining them, a deployment unprecedented in modern times. Bossasso port in successor next year. Puntland is a particular target. The unrecognised but de facto state is already at war. Heavy fighting broke out on 21 November between supporters of the deposed President, Colonel Abdullahi Yussef Ahmed, RWANDA/UGANDA 4 and backers of Jama Ali Jama, elected President by the Garowe conference of elders last week. Intelligence sources spoke of an Ethiopian invasion. Washington backs neighbouring Ethiopia, which Brothers at war is itching to defeat Islamists and Oromo rebels, and to settle old scores. Muslim Somalia itself, while Personal rivalries and battling for plagued by its own Islamists, overflows with anti-Islamist militias with no love for Usama. influence and spoils in the Congo So why is Somalia widely perceived as Usama’s next base and an upcoming target for the US-led war have stretched relations Coalition against Terrorism? So fragmented is the state, with its new Transitional National Government between Kigali and Kampala to the (AC Vol 42 No 22) forming only one authority among several, and such is the military experience of the limit. -

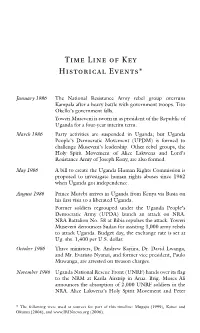

Time Line of Key Historical Events*

Time Line of Key Historical Events* January 1986 The National Resistance Army rebel group overruns Kampala after a heavy battle with government troops. Tito Okello’s government falls. Yoweri Museveni is sworn in as president of the Republic of Uganda for a four-year interim term. March 1986 Party activities are suspended in Uganda; but Uganda People’s Democratic Movement (UPDM) is formed to challenge Museveni’s leadership. Other rebel groups, the Holy Spirit Movement of Alice Lakwena and Lord’s Resistance Army of Joseph Kony, are also formed. May 1986 A bill to create the Uganda Human Rights Commission is proposed to investigate human rights abuses since 1962 when Uganda got independence. August 1986 Prince Mutebi arrives in Uganda from Kenya via Busia on his first visit to a liberated Uganda. Former soldiers regrouped under the Uganda People’s Democratic Army (UPDA) launch an attack on NRA. NRA Battalion No. 58 at Bibia repulses the attack. Yoweri Museveni denounces Sudan for assisting 3,000 army rebels to attack Uganda. Budget day, the exchange rate is set at Ug. shs. 1,400 per U.S. dollar. October 1986 Three ministers, Dr. Andrew Kayiira, Dr. David Lwanga, and Mr. Evaristo Nyanzi, and former vice president, Paulo Muwanga, are arrested on treason charges. November 1986 Uganda National Rescue Front (UNRF) hands over its flag to the NRM at Karila Airstrip in Arua. Brig. Moses Ali announces the absorption of 2,000 UNRF soldiers in the NRA. Alice Lakwena’s Holy Spirit Movement and Peter * The following were used as sources for part of this timeline: Mugaju (1999), Kaiser and Okumu (2004), and www.IRINnews.org (2006). -

Uganda, Country Information

Uganda, Country Information UGANDA ASSESSMENT April 2003 Country Information and Policy Unit I SCOPE OF DOCUMENT II GEOGRAPHY III ECONOMY IV HISTORY V STATE STRUCTURE HUMAN RIGHTS HUMAN RIGHTS ISSUES HUMAN RIGHTS - SPECIFIC GROUPS HUMAN RIGHTS - OTHER ISSUES CHRONOLOGY OF MAJOR EVENTS POLITICAL ORGANISATIONS PROMINENT PEOPLE GLOSSARY REFERENCES TO SOURCE MATERIAL 1. SCOPE OF THE DOCUMENT 1.1 This assessment has been produced by the Country Information and Policy Unit, Immigration and Nationality Directorate, Home Office, from information obtained from a wide variety of recognised sources. The document does not contain any Home Office opinion or policy. 1.2 The assessment has been prepared for background purposes for those involved in the asylum / human rights determination process. The information it contains is not exhaustive. It concentrates on the issues most commonly raised in asylum / human rights claims made in the United Kingdom. 1.3 The assessment is sourced throughout. It is intended for use by caseworkers as a signpost to the source material, which has been made available to them. The vast majority of the source material is readily available in the public domain. These sources have been checked for currency, and as far as can be ascertained, remained relevant and up to date at the time the document was issued. 1.4 It is intended to revise the assessment on a six-monthly basis while the country remains within the top 35 asylum-seeker producing countries in the United Kingdom. file:///V|/vll/country/uk_cntry_assess/apr2003/0403_Uganda.htm[10/21/2014 10:09:59 AM] Uganda, Country Information 2. -

Parliamentary Committee on Hiv/Aids Hiv/Aids Orientation

PARLIAMENTARY COMMITTEE ON HIV/AIDS HIV/AIDS ORIENTATION FOR PARLIAMENT HIV/AIDS COMMUNICATION TOOL KIT Held at SPEKE RESORT AND COUNTRY LODGE, MUNYONYO MONDAY, 9TH MAY 2005 Organized by UGANDA LEGISLATIVE SUPPORT ACTIVITY – LSA DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATES, INC. KAMPALA, UGANDA Funded by UNITED STATES AGENCY FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT – USAID UGANDA MISSION Development Associates 29TH JULY 2005 Disclaimer: The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. Table of Contents Page List of Acronyms ……………………………………………………………… ii Introduction…………………………………………………………………… 1 Introductory Remarks by the Chairperson of the HIV/AIDS Committee……... 1 Official Opening Remarks by the Representative of Speaker of Parliament….. 1 Overview and Magnitude of the HIV/AIDS Epidemic in Uganda ……………. 3 Overview and Magnitude of the HIV/AIDS Epidemic Globally ……………... 4 Core HIV/AIDS Prevention Interventions in Uganda ………………………… 5 Update on HIV/AIDS Vaccine Trials ...……………………………………... 8 Update of ARV Programme (ARV Distribution, ARV Rollout Plan, Effect of ARVs on HIV/AIDS Prevention and Challenges) ………………….. 9 Update on ARV Programme (Effect of ARVs on HIV and Challenges) …………………………………….. 11 Mapping of HIV/AIDS Activities in Uganda …………………………………. 11 Way Forward by Hon. Dora Byamukama …………………………………….. 12 Closing Remarks……………………………………...……………………….. 13 Appendix – List of Participants……………………………………………….. 15 i List of Acronyms ART - Anti-retroviral -

Uganda Assessment October 2002

UGANDA COUNTRY ASSESSMENT October 2002 Country Information & Policy Unit IMMIGRATION & NATIONALITY DIRECTORATE HOME OFFICE, UNITED KINGDOM Uganda October 2002 CONTENTS 1 Scope of Document 1.1 - 1.4 2 Geography 2.1 3 Economy 3.1 4 History 4.1 1989 Elections 4.2 - 4.3 5 State Structures 5.1 - 5.6 The Constitution 5.7 - 5.8 Citizenship & Nationality 5.9 - 5.28 Political System 5.29 - 5.33 Judiciary 5.34 Treason 5.35 Legal Rights & Detention 5.36 - 5.38 Death Penalty 5.39 - 5.49 Internal Security 5.50 - 5.57 Security Forces 5.58 - 5.63 Prisons & Prison Conditions 5.64 - 5.65 Military Service 5.66 - 5.70 Medical Services 5.71 Disabilities 5.72 - 5.75 Educational System 6 Human Rights 6A Human Rights Issues Overview 6.1 - 6.7 Human Rights Monitoring 6.8 - 6.9 Uganda Human Rights Commission 6.10 Insurgency 6.11 - 6.14 Amnesties 6.15 - 6.19 Freedom of Speech and the Media 6.20 - 6.25 Freedom of Religion 6.26 - 6.29 Freedom of Assembly & Association 6.30 - 6.32 Employment Rights 6.33 - 6.36 People Trafficking 6.37 Freedom of Movement 6.38 - 6.39 Internal Flight 6.40 Refugees 6.41 - 6.42 6B Human Rights - Specific Groups Ethnic Groups Acholi 6.43 - 6.46 Karamojong 6.47 - 6.56 Uganda October 2002 Women 6.57 - 6.60 Children 6.61 - 6.64 Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) 6.65 - 6.73 Homosexuals 6.74 - 6.75 Religious Groups 6.76 Movement for the Restoration of the Ten Commandments of God Rebel Groups 6.77 - 6.82 Lords Resistance Army (LRA) 6.83 - 6.86 Aims of the LRA 6.87 - 6.96 Latest LRA Attacks 6.97 - 6.105 UPDF reception of the LRA 6.106 - 6.108 Allied -

To Download the PDF File

IS THE REVOLUTION HERE YET? IMPACT OF MOBILE PHONES AND THE INTERNET ON UGANDA'S NEWS MEDIA AND PUBLIC LIFE GAAKIKIGAMBO Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Journalism School of Journalism and Communication Carleton University Ottawa, Canada April, 2010 © Gaaki Kigambo 2010 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaONK1A0N4 OttawaONK1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-68657-7 Our file Notre r6f6rence ISBN: 978-0-494-68657-7 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

MAKERERE SUPPLEMENT SHORT.Indd

MAKERERE UNIVERSITY MAKERERE UNIVERSITY we build for the future we build for the future 3 2 3 cated all this by awarding him the Secretariat. A Uganda, born He was a leading national- ment. In his book (Not Yet devotedly served as chancellor for Doctor of Laws (Honoris Causa) of 44 years ago, Eriyo has since ist and political agitator in the Uhuru), Mzee Jaramogi Odinga Makerere University as well. Makerere University. PRO Ritah April 2012 been Deputy EAC independence struggle for Nyasa- reveals that he did his A’levels at Secretary General in charge of land which became Malawi after Alliance High School after which Namisango says they were recog- JULIUS NYERERE nizing his outstanding record of Productive and Social Sectors. independence. Born on Novem- he went to Makerere University excellence in diplomacy, journal- She has a Bachelors degree in ber 22 1929, Murray William in 1940. Thereafter he returned Julius Kambarage Nyerere ism, administration, governance; Social Sciences, a Post Graduate Kanyama Chiume, a Makerere to Kenya to teach at a second- was born on April 13th 1922 and BUILDING regional and global politics. Diploma in Education (PGDE) graduate was synonymous ary school- Maseno High School died on October 14th 1999. The and a Master’s degree in arts-all with the Malawi independence until 1948 when he joined Kenya Tanzanian founding president was from Makerere University. A struggle of the 1950s-1960s. He African Union (KAU), one of an alumnus of Makerere Univer- RICHARD SEZIBERA proud Makererean, Jessica Eriyo was also one of the leaders of the the political parties then fighting sity. -

Negotiating (Trans)National Identities in Ugandan Literature Danson

Negotiating (Trans)national Identities in Ugandan Literature Danson Sylvester Kahyana Dissertation presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Prof. Tina Steiner Co-supervisor: Dr. Lynda Gichanda Spencer English Department Stellenbosch University April 2014 Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za Declaration I declare that this dissertation is my own work and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. April 2014 Copyright © 2014 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved ii Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za Dedication For my mother, Kabiira Pulisima; my wife, Roselyne Tiperu Ajiko; and our children, Isabelle Soki Asikibawe, Christabelle Biira Nimubuya, Annabelle Kabugho Nimulhamya, and Rosebelle Mbambu Asimawe In memory of My father, Daniel Bwambale Nkuku; my maternal grandmother, Masika Maliyamu Federesi; my high school literature teacher, Mrs Jane Ayebare; and my friend, Giovanna Orlando. iii Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za Abstract This thesis examines how selected Ugandan literary texts portray constructions and negotiations of national identities as they intersect with overlapping and cross-cutting identities like race, ethnicity, gender, religious denomination, and political affiliation. The word “negotiations” is central to the close reading of selected focal texts I offer in this thesis for it implies that there are times when a tension may arise between national identity and one or more of these other identities (for instance when races or ethnic groups are imagined outside the nation as foreigners) or between one national identity (say Ugandan) and other national identities (say British) for those characters who occupy more than one national space and whose understanding of home therefore includes a here (say Britain) and a there (say Uganda).