DISASTER RISK MANAGEMENT and OIL PRODUCTION in UGANDA: NEED for a WIN to WIN APPROACH INPUT PAPER Prepared for the Global Assess

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UGANDA COUNTRY REPORT October 2004 Country

UGANDA COUNTRY REPORT October 2004 Country Information & Policy Unit IMMIGRATION & NATIONALITY DIRECTORATE HOME OFFICE, UNITED KINGDOM Uganda Report - October 2004 CONTENTS 1. Scope of the Document 1.1 - 1.10 2. Geography 2.1 - 2.2 3. Economy 3.1 - 3.3 4. History 4.1 – 4.2 • Elections 1989 4.3 • Elections 1996 4.4 • Elections 2001 4.5 5. State Structures Constitution 5.1 – 5.13 • Citizenship and Nationality 5.14 – 5.15 Political System 5.16– 5.42 • Next Elections 5.43 – 5.45 • Reform Agenda 5.46 – 5.50 Judiciary 5.55 • Treason 5.56 – 5.58 Legal Rights/Detention 5.59 – 5.61 • Death Penalty 5.62 – 5.65 • Torture 5.66 – 5.75 Internal Security 5.76 – 5.78 • Security Forces 5.79 – 5.81 Prisons and Prison Conditions 5.82 – 5.87 Military Service 5.88 – 5.90 • LRA Rebels Join the Military 5.91 – 5.101 Medical Services 5.102 – 5.106 • HIV/AIDS 5.107 – 5.113 • Mental Illness 5.114 – 5.115 • People with Disabilities 5.116 – 5.118 5.119 – 5.121 Educational System 6. Human Rights 6.A Human Rights Issues Overview 6.1 - 6.08 • Amnesties 6.09 – 6.14 Freedom of Speech and the Media 6.15 – 6.20 • Journalists 6.21 – 6.24 Uganda Report - October 2004 Freedom of Religion 6.25 – 6.26 • Religious Groups 6.27 – 6.32 Freedom of Assembly and Association 6.33 – 6.34 Employment Rights 6.35 – 6.40 People Trafficking 6.41 – 6.42 Freedom of Movement 6.43 – 6.48 6.B Human Rights Specific Groups Ethnic Groups 6.49 – 6.53 • Acholi 6.54 – 6.57 • Karamojong 6.58 – 6.61 Women 6.62 – 6.66 Children 6.67 – 6.77 • Child care Arrangements 6.78 • Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) -

Speech to Parliament by H.E. Yoweri Kaguta Museveni President of The

Speech to Parliament By H.E. Yoweri Kaguta Museveni President of the Republic of Uganda Parliamentary Buildings - 13th December, 2012 1 Rt. Hon. Speaker, I have decided to use the rights of the President, under Article 101 (2) of the 1995 Constitution of the Republic of Uganda, to address Parliament. I am exercising this right in order to counter the nefarious and mendacious campaign of the foreign interests, using NGOs and some Members of Parliament, to try and cripple or disorient the development of the Oil sector. If the Ugandans may remember, this is not the first time these interests try to distort the development of our history. When we were fighting the Sudanese-sponsored terrorism of Kony or when we were fighting the armed cattle- rustlers in Karamoja, you remember, there were groups, including some religious leaders, Opposition Members of Parliament as well as NGOs, which would spend all the 2 time denouncing us, the Freedom Fighters. They were denouncing those who were fighting to defend the lives and properties of the people, rather than denouncing the terrorists, the cattle-rustlers and their external-backers (in the case of Kony) as well as their internal collaborators. It would appear as if the wrong-doer was the Government, the NRM, rather than the criminals. We, patiently, put up with that malignment at the same time as we fought, got injured or killed, against the enemy until we achieved victory. Eventually, we won, supported by the ordinary people and the different people’s militias. There is total peace in the whole country and yet the misleaders of those years have not apologized to the Ugandans for their mendacity. -

RG Combined Handbooks 2019

Combined General Handbooks 1 Vision and Application Handbook Welcome to the Restoration Gateway (RG) family. As with all families, there are spoken and unspoken policies that should help each family member grow in God’s grace and help the whole family effectively serve the Lord. These handbooks are a work in progress designed to outline some of the spoken policies that guide us here. The overarching policy is to love the Lord your God with all your heart, soul, mind and strength, and your neighbor as yourself. The RG team is committed to work together with you to plan ministry and work opportunities that are mutually beneficial for your team, RG and for surrounding communities. Here is a list of resources that are available as you prepare for your trip to RG: 1. Vision and Application Handbook – The purpose of this is to give you first steps for initiating a trip to RG. After approval, the “Preparing and Arriving”, “Budgeting Planning Handbook”, and the” Q&A Handbook” resources will be helpful. 2. Preparing and Arriving Handbook – This handbook will give you details about what to do before you arrive and what you need to know about arriving in Uganda and RG. 3. Budgeting Planning Handbook – Within these pages is information you’ll need about budgeting for your trip and how to access money in Uganda. 4. Q & A Handbook – We know many questions arise when preparing and arriving for a trip, so please check this document for any questions you may have. The below information is designed to help you better understand how to serve at RG. -

Karuma Dam EIA Report Part 2

KARUMA HPP(600MW)_________________________________________________ EIPL CHAPTER-1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 BACKGROUND Uganda is a landlocked country in East Africa, bordered on the east by Kenya, on the north by Sudan, on the west by the Democratic Republic of the Congo, on the southwest by Rwanda, and on the south by Tanzania. Uganda has a total landmass of 241,000 sq. km, 18 percent of which is covered by freshwater bodies. Lying astride the equator, Uganda offers exceptional diversity, combining some of the best features of Africa, including the source of the River Nile(the second longest river in the World) and Lake Victoria(the second largest fresh water lake in the World). The country’s geographical diversity is great. In the East, it overlaps the tropical Savannah and in the West, African rain-forest zones lies. Moreover, there are many existing contrasting physical features, ranging from extensive plains with undulating hills to snow-capped mountains, waterfalls, meandering rivers and spectacular flora and fauna. The country is endowed with abundant renewable energy resources. These include plentiful biomass supplies, extensive hydrological resources, favorable solar conditions and large quantities of biomass residues from agricultural production, among others. With about 43,942 km 2 of wetlands and open water (18% of total area), Uganda is considered fairly well endowed with water resources. Major water bodies include lakes Victoria, Kyoga, Albert, George and Edward while major rivers include the Nile, Ruizi, Katonga, Kafu, Mpologoma and Aswa. Almost the whole of Uganda lies within the Nile basin, which is shared by 10 countries. Favorable atmospheric conditions and mighty river provides abundant hydropower potential estimated at about 2,000 MW mainly along River Nile that can be developed to supply isolated areas or feed into the national grid. -

Vote:017 Ministry of Energy and Mineral Development V1: Vote Overview I

Ministry of Energy and Mineral Development Ministerial Policy Statement FY 2019/20 Vote:017 Ministry of Energy and Mineral Development V1: Vote Overview I. Vote Mission Statement ³To ensure reliable, adequate and sustainable exploitation, management and utilization of energy and mineral resources for the inclusion and benefit of all people in Uganda´ II. Strategic Objective a. To meet the energy needs of Uganda's population for social and economic development in an environmentally sustainable manner b. To use the country's oil and gas resources to contribute to early achievement of poverty eradication and create lasting value to society c. To develop the mineral sector for it to contribute significantly to sustainable national economic and social growth III. Major Achievements in 2018/19 ENERGY PLANNING MANAGEMENT AND INFRASTRUCTURE DEVELOPMENT Karuma HPP (600MW) physical progress was as at 89% as at 15th February 2019; Isimba HPP (183MW) final commissioning tests have been done and is already delivering power to the grid. The official commissioning is expected on 21st March 2019; Agago ±Achwa (42MW): The plant is undergoing final commissioning test. Electricity Transmission Projects: The following transmission projects were completed: Kawanda-Masaka T-Line 220kV, 137km line; Kawanda and Masaka substations; Nkenda-Fort Portal -Hoima 220kV, 226km line and associated Substations; Mbarara-Nkenda 132kV 160km; and the Isimba- Bujagali Interconnection project132kV, 41km line, Mbarara-Mirama 220kV, 65km line. The following transmission lines -

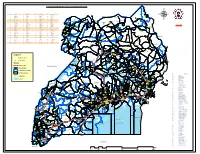

Legend " Wanseko " 159 !

CONSTITUENT MAP FOR UGANDA_ELECTORAL AREAS 2016 CONSTITUENT MAP FOR UGANDA GAZETTED ELECTORAL AREAS FOR 2016 GENERAL ELECTIONS CODE CONSTITUENCY CODE CONSTITUENCY CODE CONSTITUENCY CODE CONSTITUENCY 266 LAMWO CTY 51 TOROMA CTY 101 BULAMOGI CTY 154 ERUTR CTY NORTH 165 KOBOKO MC 52 KABERAMAIDO CTY 102 KIGULU CTY SOUTH 155 DOKOLO SOUTH CTY Pirre 1 BUSIRO CTY EST 53 SERERE CTY 103 KIGULU CTY NORTH 156 DOKOLO NORTH CTY !. Agoro 2 BUSIRO CTY NORTH 54 KASILO CTY 104 IGANGA MC 157 MOROTO CTY !. 58 3 BUSIRO CTY SOUTH 55 KACHUMBALU CTY 105 BUGWERI CTY 158 AJURI CTY SOUTH SUDAN Morungole 4 KYADDONDO CTY EST 56 BUKEDEA CTY 106 BUNYA CTY EST 159 KOLE SOUTH CTY Metuli Lotuturu !. !. Kimion 5 KYADDONDO CTY NORTH 57 DODOTH WEST CTY 107 BUNYA CTY SOUTH 160 KOLE NORTH CTY !. "57 !. 6 KIIRA MC 58 DODOTH EST CTY 108 BUNYA CTY WEST 161 OYAM CTY SOUTH Apok !. 7 EBB MC 59 TEPETH CTY 109 BUNGOKHO CTY SOUTH 162 OYAM CTY NORTH 8 MUKONO CTY SOUTH 60 MOROTO MC 110 BUNGOKHO CTY NORTH 163 KOBOKO MC 173 " 9 MUKONO CTY NORTH 61 MATHENUKO CTY 111 MBALE MC 164 VURA CTY 180 Madi Opei Loitanit Midigo Kaabong 10 NAKIFUMA CTY 62 PIAN CTY 112 KABALE MC 165 UPPER MADI CTY NIMULE Lokung Paloga !. !. µ !. "!. 11 BUIKWE CTY WEST 63 CHEKWIL CTY 113 MITYANA CTY SOUTH 166 TEREGO EST CTY Dufile "!. !. LAMWO !. KAABONG 177 YUMBE Nimule " Akilok 12 BUIKWE CTY SOUTH 64 BAMBA CTY 114 MITYANA CTY NORTH 168 ARUA MC Rumogi MOYO !. !. Oraba Ludara !. " Karenga 13 BUIKWE CTY NORTH 65 BUGHENDERA CTY 115 BUSUJJU 169 LOWER MADI CTY !. -

Executive Summary

KARUMA HPP (600 MW) __________________________________________ EIPL Executive Summary Uganda is currently facing a huge electricity supply deficit; it has one of the world’s lowest levels of electricity development as well as the lowest per capita electricity consumption. Over 90 percent of the country's population is not connected to the national grid, much of the electricity network at present is poorly maintained and country the experiences frequent power cuts. According to the National Development Plan (NDP- 2010/11-2014) the present peak demand of Uganda is about 400 MW or more which has been growing at an annual rate of 8%, to meet this growth with demand about 20 MW of new generating capacity needs to be added each year. NDP further identifies that, current levels of electricity supply cannot support heavy industries limited generation capacity and corresponding limited transmission and distribution network as among other key constraints to the performance of the energy sector in the country. Given the large and growing gap between electricity supply and demand in Uganda, a number of electricity generation alternatives were explored under Rural Electrification Programme for next 20 years. Studies over various planning horizons were also examined and prioritized for the country under the Hydropower Master Plan. The conclusions from the evaluation of these generation alternatives reveals that large scale hydroelectric development is the most economical way forward for the country in the short-medium term. Therefore, to meet the growing electricity demand seven potential hydropower sites have been examined downstream of Bujagali Hydro Power Project (which is already under construction) over River Victoria Nile from Lake Victoria to Lake Albert as river is the primary hydrological resource available in country. -

Uganda National Roads Network

UGANDA NATIONAL ROADS NETWORK REPUBLIC OF SOUTH SUDAN Musingo #" !P Kidepo a w K ± r i P !P e t Apoka gu a K m #" lo - g - L a o u k - #" g u P i #" n d Moyo!P g o i #"#" - t #"#" N i k #" KOBOKO M e g a #" #" #" l Nimule o #"!P a YUMBE #" u!P m ng m o #" e #" Laropi i #" ro ar KAABONG #" !P N m K #" (! - o - te o e om Kaabong#"!P g MOYO T c n o #" o #" L be Padibe !P - b K m !P LAMWO #" a oboko - Yu Yumbe #" om r K #" #" #" O #" Koboko #" #" - !P !P o Naam REGIONS AND STATIONS Moy n #" Lodonga Adjumani#" Atiak - #" Okora a #" Obongi #" !P #" #" a Loyoro #" p #" Ob #" KITGUM !P !P #" #" ong !P #" #" m A i o #" - #" - K #" Or u - o lik #" m L Omugo ul #" !P u d #" in itg o i g Kitgum t Maracha !P !P#" a K k #" !P #" #"#" a o !P p #" #" #" Atiak K #" e #" (!(! #" Kitgum Matidi l MARACHA P e - a #" A #"#" e #" #" ke d #" le G d #" #" i A l u a - Kitgum - P l n #" #" !P u ADJUMANI #" g n a Moyo e !P ei Terego b - r #" ot Kotido vu #" b A e Acholibur - K o Arua e g tr t u #" i r W #" o - O a a #" o n L m fe di - k Atanga KOTIDO eli #" ilia #" Rh #" l p N o r t h #"#" B ino Rhino !P o Ka Gulu !P ca #" #"#" aim ARUA mp - P #" #" !P Kotido Arua #" Camp Pajule go #" !P GULU on #" !P al im #" !PNariwo #" u #" - K b A ul r A r G de - i Lira a - Pa o a Bondo #" Amuru Jun w id m Moroto Aru #" ctio AMURU s ot !P #" n - A o #" !P A K i !P #" #" PADER N o r t h E a s t #" Inde w Kilak #" - #" e #" e AGAGO K #"#" !P a #" #" #" y #" a N o #" #" !P #" l w a Soroti e #"#" N Abim b - Gulu #" - K d ilak o b u !P #" Masindi !P i um !P Adilang n - n a O e #" -

Kiryandongo District HRV Profile.Pdf

Kiryandongo District Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability Profi le 2016 Acknowledgement On behalf of Office of the Prime Minister, I wish to express my sincere appreciation to all of the key stakeholders who provided their valuable inputs and support to this Multi-Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability mapping exercise that led to the production of comprehensive district Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability (HRV) profiles. I extend my sincere thanks to the Department of Relief, Disaster Preparedness and Management, under the leadership of the Commissioner, Mr. Martin Owor, for the oversight and management of the entire exercise. The HRV assessment team was led by Ms. Ahimbisibwe Catherine, Senior Disaster Preparedness Officer supported by Ogwang Jimmy, Disaster Preparedness Officer and the team of consultants (GIS/DRR specialists); Dr. Bernard Barasa, and Mr. Nsiimire Peter, who provided technical support. Our gratitude goes to UNDP for providing funds to support the Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability Mapping. The team comprised of Mr. Steven Goldfinch – Disaster Risk Management Advisor, Mr. Gilbert Anguyo - Disaster Risk Reduction Analyst, and Mr. Ongom Alfred- Early Warning system Database programmer. My appreciation also goes to Kiryandongo District Team. The entire body of stakeholders who in one way or another yielded valuable ideas and time to support the completion of this exercise. Hon. Hilary O. Onek Minister for Relief, Disaster Preparedness and Refugees KIRYANDONGO DISTRICT HAZARD, RISK AND VULNERABILITY PROFILE i TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENT .................................................................................................................i -

Collapse, War and Reconstruction in Uganda

Working Paper No. 27 - Development as State-Making - COLLAPSE, WAR AND RECONSTRUCTION IN UGANDA AN ANALYTICAL NARRATIVE ON STATE-MAKING Frederick Golooba-Mutebi Makerere Institute of Social Research Makerere University January 2008 Copyright © F. Golooba-Mutebi 2008 Although every effort is made to ensure the accuracy and reliability of material published in this Working Paper, the Crisis States Research Centre and LSE accept no responsibility for the veracity of claims or accuracy of information provided by contributors. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission in writing of the publisher nor be issued to the public or circulated in any form other than that in which it is published. Requests for permission to reproduce this Working Paper, of any part thereof, should be sent to: The Editor, Crisis States Research Centre, DESTIN, LSE, Houghton Street, London WC2A 2AE. Crisis States Working Papers Series No.2 ISSN 1749-1797 (print) ISSN 1749-1800 (online) 1 Crisis States Research Centre Collapse, war and reconstruction in Uganda An analytical narrative on state-making Frederick Golooba-Mutebi∗ Makerere Institute of Social Research Abstract Since independence from British colonial rule, Uganda has had a turbulent political history characterised by putsches, dictatorship, contested electoral outcomes, civil wars and a military invasion. There were eight changes of government within a period of twenty-four years (from 1962-1986), five of which were violent and unconstitutional. This paper identifies factors that account for these recurrent episodes of political violence and state collapse. -

Energy and Minerals Development Sector

ENERGY AND MINERALS DEVELOPMENT SECTOR SEMI-ANNUAL BUDGET MONITORING REPORT FINANCIAL YEAR 2019/20 APRIL 2020 MOFPED #DoingMore Energy and Minerals Development Sector: Semi-Annual Budget Monitoring Report - FY 2019/20 A ENERGY AND MINERALS DEVELOPMENT SECTOR SEMI-ANNUAL BUDGET MONITORING REPORT FINANCIAL YEAR 2019/20 APRIL 2020 MOFPED #DoingMore Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ........................................................................................................... ii FOREWORD ......................................................................................................................................................... v EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................................................................vi CHAPTER 1: BACKGROUND ......................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................................................1 1.2 Sector Outcomes ....................................................................................................................................................................2 1.3 Sector Priorities ........................................................................................................................................................................2 -

Report of the Auditor General on the Financial Statements Of

THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA REPORT OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL ON THE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS OF THE UGANDA ELECTRICITY TRANSMISSION COMPANY LIMITED KARUMA INTERCONNECTION PROJECT FEASIBILITY STUDY TH ST FOR PERIOD 5 NOVEMBER, 2009 TO 31 DECEMBER, 2013 OFFICE OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL KAMPALA TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE LIST OF ACRONYMS ..................................................................................................... 1 REPORT OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL ON THE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS OF THE UGANDA ELECTRICITY TRANSMISSION COMPANY LIMITED-KARUMA INTERCONNECTION PROJECT FEASIBILITY STUDY FOR THE PERIOD 5THNOVEMBER, 2009 TO 31STDECEMBER, 2013 ...... 2 DETAILED REPORT OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL ON THE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS OF THE UGANDA ELECTRICITY TRANSMISSION COMPANY LIMITED-KARUMA INTERCONNECTION PROJECT FEASIBILITY STUDY FOR THE PERIOD 5THNOVEMBER, 2009 TO 31ST DECEMBER, 2013 ............................................................................................................................ 4 1.0. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................. 4 2.0. BACKGROUND INFORMATION ............................................................................. 4 3.0. THE PROJECT SCOPE .......................................................................................... 5 4.0. AUDIT OBJECTIVES ............................................................................................ 7 5.0. PROCEDURES PERFORMED .................................................................................