Country Reviews of Capacity Development: the Case of Uganda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kamwenge District Local Government

KAMWENGE DISTRICT LOCAL GOVERNMENT FIVE-YEAR DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2015/2016 – 2019/2020 Vision The vision of Kamwenge District is ‚Improved quality of life for all the people of Kamwenge by the year 2030‛. Theme Sustainable wealth creation through infrastructure development, food security and environment conservation for a healthy and productive population” Approved by the District Council under Minute 46/COU/2014/2015 REVISED EDITION 2016 i LIST OF ACRONYMS ACODEV Action for Community Development ADRA Adventist Relief Agency ARVs Anti Retroviral drugs BFP Budget Framework Programme BMUs Beach Management Units CAO Chief Administrative Officer CBO Community Based Organisation CBS Community Based Services CDD Community Driven Development CDO Community Development Officer CFO Chief Finance Officer CNDPF Comprehensive National Development Planning Framework CORPs Community Own Resource Persons CSO Civil Society Organisation DDP District Development plan DHO District Health Officer DISO District Internal Security Officer DLSP District Livelihoods Support Programme DNRO District Natural Resources Office DWSCC District Water and Sanitation Coordination Committee FAL Functional Adult Literacy GFS Gravity Flow Scheme HEWASA Health through Water and Sanitation HLG Higher Local Government HMIS Health Management Information System HSD Health Sub District IGAs Income Generating Activities IMCI Integrated Management of Child Illness JESE Joint Effort to Save the Environment KABECOS Kamwenge Bee keepers Association KRC Kabarole Research and Resource Centre -

Uganda National Roads Authority Road Sector

THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA UGANDA NATIONAL ROADS AUTHORITY ROAD SECTOR SUPPORT PROJECT 3 (RSSP 3) REPORT OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL ON THE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS FOR THE FINANCIAL YEAR ENDED 30TH JUNE 2013 OFFICE OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL UGANDA TABLE OF CONTENTS Item Page No. Report of the Auditor General on the financial statements for the year iii-iv ended 30th June 2013 REPORT 1. Introduction 1 2. Project Background 1 3. Project Objectives 2 4. Audit Objectives 2 5. Audit Procedures 3 6. FINDINGS 6.1 Compliance with Financing Agreements and GoU Financial Regulations 4 6.2 General Standard of Accounting and Internal Control 6 6.3 Status of Prior Year Audit Recommendations 7 Appendix 1: Financial Statements ii ROAD SECTOR SUPPORT PROJECT 3 (RSSP 3) PROJECT ID NO.P-UG-DB0-020 AND LOAN NO. 2100150020793 REPORT OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL ON THE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 30th JUNE 2013 THE RT. HON. SPEAKER OF PARLIAMENT I have audited the financial statements of Road Sector Support Project 3 (RSSP 3) for the year ended 30th June 2013. The financial statements are set out on pages 17 to 24 in Appendix 1 and comprise of; Statement of receipts and payments; Statement of fund balances; Notes to the financial statements, including a summary of significant accounting policies used. Project Management’s responsibility for the financial statements The Management of UNRA, (the RSSP-3 implementing agency) are responsible for the preparation of the financial statements. This responsibility includes: designing, implementing and maintaining internal control relevant to the preparation and fair presentation of financial statements that are free from material misstatements, whether due to fraud or error; selecting and applying appropriate accounting policies; and making accounting estimates that are reasonable in the circumstances. -

Speech to Parliament by H.E. Yoweri Kaguta Museveni President of The

Speech to Parliament By H.E. Yoweri Kaguta Museveni President of the Republic of Uganda Parliamentary Buildings - 13th December, 2012 1 Rt. Hon. Speaker, I have decided to use the rights of the President, under Article 101 (2) of the 1995 Constitution of the Republic of Uganda, to address Parliament. I am exercising this right in order to counter the nefarious and mendacious campaign of the foreign interests, using NGOs and some Members of Parliament, to try and cripple or disorient the development of the Oil sector. If the Ugandans may remember, this is not the first time these interests try to distort the development of our history. When we were fighting the Sudanese-sponsored terrorism of Kony or when we were fighting the armed cattle- rustlers in Karamoja, you remember, there were groups, including some religious leaders, Opposition Members of Parliament as well as NGOs, which would spend all the 2 time denouncing us, the Freedom Fighters. They were denouncing those who were fighting to defend the lives and properties of the people, rather than denouncing the terrorists, the cattle-rustlers and their external-backers (in the case of Kony) as well as their internal collaborators. It would appear as if the wrong-doer was the Government, the NRM, rather than the criminals. We, patiently, put up with that malignment at the same time as we fought, got injured or killed, against the enemy until we achieved victory. Eventually, we won, supported by the ordinary people and the different people’s militias. There is total peace in the whole country and yet the misleaders of those years have not apologized to the Ugandans for their mendacity. -

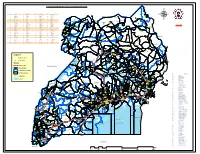

UGANDA: PLANNING MAP (Details)

IMU, UNOCHA Uganda http://www.ugandaclusters.ug http://ochaonline.un.org UGANDA: PLANNING MAP (Details) SUDAN NARENGEPAK KARENGA KATHILE KIDEPO NP !( NGACINO !( LOPULINGI KATHILE AGORO AGU FR PABAR AGORO !( !( KAMION !( Apoka TULIA PAMUJO !( KAWALAKOL RANGELAND ! KEI FR DIBOLYEC !( KERWA !( RUDI LOKWAKARAMOE !( POTIKA !( !( PAWACH METU LELAPWOT LAWIYE West PAWOR KALAPATA MIDIGO NYAPEA FR LOKORI KAABONG Moyo KAPALATA LODIKO ELENDEREA PAJAKIRI (! KAPEDO Dodoth !( PAMERI LAMWO FR LOTIM MOYO TC LICWAR KAPEDO (! WANDI EBWEA VUURA !( CHAKULYA KEI ! !( !( !( !( PARACELE !( KAMACHARIKOL INGILE Moyo AYUU POBURA NARIAMAOI !( !( LOKUNG Madi RANGELAND LEFORI ALALI OKUTI LOYORO AYIPE ORAA PAWAJA Opei MADI NAPORE MORUKORI GWERE MOYO PAMOYI PARAPONO ! MOROTO Nimule OPEI PALAJA !( ALURU ! !( LOKERUI PAMODO MIGO PAKALABULE KULUBA YUMBE PANGIRA LOKOLIA !( !( PANYANGA ELEGU PADWAT PALUGA !( !( KARENGA !( KOCHI LAMA KAL LOKIAL KAABONG TEUSO Laropi !( !( LIMIDIA POBEL LOPEDO DUFILE !( !( PALOGA LOMERIS/KABONG KOBOKO MASALOA LAROPI ! OLEBE MOCHA KATUM LOSONGOLO AWOBA !( !( !( DUFILE !( ORABA LIRI PALABEK KITENY SANGAR MONODU LUDARA OMBACHI LAROPI ELEGU OKOL !( (! !( !( !( KAL AKURUMOU KOMURIA MOYO LAROPI OMI Lamwo !( KULUBA Koboko PODO LIRI KAL PALORINYA DUFILE (! PADIBE Kaabong LOBONGIA !( LUDARA !( !( PANYANGA !( !( NYOKE ABAKADYAK BUNGU !( OROM KAABONG! TC !( GIMERE LAROPI PADWAT EAST !( KERILA BIAFRA !( LONGIRA PENA MINIKI Aringa!( ROMOGI PALORINYA JIHWA !( LAMWO KULUYE KATATWO !( PIRE BAMURE ORINJI (! BARINGA PALABEK WANGTIT OKOL KINGABA !( LEGU MINIKI -

RG Combined Handbooks 2019

Combined General Handbooks 1 Vision and Application Handbook Welcome to the Restoration Gateway (RG) family. As with all families, there are spoken and unspoken policies that should help each family member grow in God’s grace and help the whole family effectively serve the Lord. These handbooks are a work in progress designed to outline some of the spoken policies that guide us here. The overarching policy is to love the Lord your God with all your heart, soul, mind and strength, and your neighbor as yourself. The RG team is committed to work together with you to plan ministry and work opportunities that are mutually beneficial for your team, RG and for surrounding communities. Here is a list of resources that are available as you prepare for your trip to RG: 1. Vision and Application Handbook – The purpose of this is to give you first steps for initiating a trip to RG. After approval, the “Preparing and Arriving”, “Budgeting Planning Handbook”, and the” Q&A Handbook” resources will be helpful. 2. Preparing and Arriving Handbook – This handbook will give you details about what to do before you arrive and what you need to know about arriving in Uganda and RG. 3. Budgeting Planning Handbook – Within these pages is information you’ll need about budgeting for your trip and how to access money in Uganda. 4. Q & A Handbook – We know many questions arise when preparing and arriving for a trip, so please check this document for any questions you may have. The below information is designed to help you better understand how to serve at RG. -

ORTHODOX-CHURCH-UGANDA.Pdf

PUBLICATION: ΕΚΔΟΣΙΣ: HOLY METROPOLIS OF KAMPALA AND ALL UGANDA ΙΕΡΑ ΜΗΤΡΟΠΟΛΙΣ ΚΑΜΠΑΛΑΣ ΚΑΙ ΠΆΣΗΣ ΟΥΓΚΑΝΤΑΣ P.OBOX 3970 KAMPALA Tel: +256 414 542461 P,O,BOX 3970 KAMPALA Fax: “ “ “ TEL: +256 414 542461 E-mail: [email protected] FAX: +256 414 542461 E-mail : [email protected] PHOTOGRAPHIC ARCHIVE, INFORMATION MATERIAL ΦΩΤΟΓΡΑΦΙΚΟΝ ΑΡΧΕΙΟΝ / ΠΛΗΡΟΦΟΡΙΚΟΝ ΥΛΙΚΟΝ SOURCE: ΠΗΓΗ: Parishes, sub-parishes, priests, Laity Parish Nuclei, Holy Churches, Mysteries Ενορίες, Υπενορίες, Ιερείς, Λαικοί Ceremonies, Celibates, Commisions Ενοριακοί πυρήνες,Ιεροί Ναοί, Μυστήρια Τελετές, Μονάζοντες, Μονάζοντες Schools, Dormitories, Orphanages Επιτροπείες, Συμβούλια Learners, Teaching Personnel Helpers, Ground Pitches Σχολεία, Οικοτροφεία, Ορφανοτροφεία Μαθητευόμενοι. Διδακτικό Προσωπικό Patients,Doctors, Nurses, Health Centres Βοηθοί, Γήπεδα Unit of Roaming Doctors Groups of Mission Doctors Ασθενείς,Ιατροί, Νοσοκόμοι, Κέντρα Υγείας Περιφερόμενη Ιατρική Μονάδα Youth Union, Mothers Union/ladies Ιεραποστολικές Ιατρικές Ομάδες Non Governmental Organisation UOCCAP Publishing House, Social Centres Ένωση Νεολαίας, Ένωση Μητέρων/ Γυναικών Construction groups Μή Κυβερνητικός Οργανισμός UOCCAP Cultivations,Animal Husbandry, catle Εκδοτικός Οίκος, Κέντρα Εκδηλώσεων breeding Office property and Land Οικοδομικές Ομάδες Central Diaconates Καλλιέργειες, Κτηνοτροφίες EDITORIAL COMMITTEE: Γραφείο / Τμήμα Κτημάτων και Οικοπέδων Mr. Theodore KATO, (Theologian), Secretary General IMK-Uganda Κεντρικά Διακονήματα¨ Mr. Richard BAYEGO (Teacher), Asst. Secretary, -

Karuma Dam EIA Report Part 2

KARUMA HPP(600MW)_________________________________________________ EIPL CHAPTER-1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 BACKGROUND Uganda is a landlocked country in East Africa, bordered on the east by Kenya, on the north by Sudan, on the west by the Democratic Republic of the Congo, on the southwest by Rwanda, and on the south by Tanzania. Uganda has a total landmass of 241,000 sq. km, 18 percent of which is covered by freshwater bodies. Lying astride the equator, Uganda offers exceptional diversity, combining some of the best features of Africa, including the source of the River Nile(the second longest river in the World) and Lake Victoria(the second largest fresh water lake in the World). The country’s geographical diversity is great. In the East, it overlaps the tropical Savannah and in the West, African rain-forest zones lies. Moreover, there are many existing contrasting physical features, ranging from extensive plains with undulating hills to snow-capped mountains, waterfalls, meandering rivers and spectacular flora and fauna. The country is endowed with abundant renewable energy resources. These include plentiful biomass supplies, extensive hydrological resources, favorable solar conditions and large quantities of biomass residues from agricultural production, among others. With about 43,942 km 2 of wetlands and open water (18% of total area), Uganda is considered fairly well endowed with water resources. Major water bodies include lakes Victoria, Kyoga, Albert, George and Edward while major rivers include the Nile, Ruizi, Katonga, Kafu, Mpologoma and Aswa. Almost the whole of Uganda lies within the Nile basin, which is shared by 10 countries. Favorable atmospheric conditions and mighty river provides abundant hydropower potential estimated at about 2,000 MW mainly along River Nile that can be developed to supply isolated areas or feed into the national grid. -

THE UGANDA GAZETTE [13Th J Anuary

The THE RH Ptrat.ir OK I'<1 AND A T IE RKPt'BI.IC OF UGANDA Registered at the Published General Post Office for transmission within by East Africa as a Newspaper Uganda Gazette A uthority Vol. CX No. 2 13th January, 2017 Price: Shs. 5,000 CONTEXTS P a g e General Notice No. 12 of 2017. The Marriage Act—Notice ... ... ... 9 THE ADVOCATES ACT, CAP. 267. The Advocates Act—Notices ... ... ... 9 The Companies Act—Notices................. ... 9-10 NOTICE OF APPLICATION FOR A CERTIFICATE The Electricity Act— Notices ... ... ... 10-11 OF ELIGIBILITY. The Trademarks Act—Registration of Applications 11-18 Advertisements ... ... ... ... 18-27 I t is h e r e b y n o t if ie d that an application has been presented to the Law Council by Okiring Mark who is SUPPLEMENTS Statutory Instruments stated to be a holder of a Bachelor of Laws Degree from Uganda Christian University, Mukono, having been No. 1—The Trade (Licensing) (Grading of Business Areas) Instrument, 2017. awarded on the 4th day of July, 2014 and a Diploma in No. 2—The Trade (Licensing) (Amendment of Schedule) Legal Practice awarded by the Law Development Centre Instrument, 2017. on the 29th day of April, 2016, for the issuance of a B ill Certificate of Eligibility for entry of his name on the Roll of Advocates for Uganda. No. 1—The Anti - Terrorism (Amendment) Bill, 2017. Kampala, MARGARET APINY, 11th January, 2017. Secretary, Law Council. General N otice No. 10 of 2017. THE MARRIAGE ACT [Cap. 251 Revised Edition, 2000] General Notice No. -

Vote:017 Ministry of Energy and Mineral Development V1: Vote Overview I

Ministry of Energy and Mineral Development Ministerial Policy Statement FY 2019/20 Vote:017 Ministry of Energy and Mineral Development V1: Vote Overview I. Vote Mission Statement ³To ensure reliable, adequate and sustainable exploitation, management and utilization of energy and mineral resources for the inclusion and benefit of all people in Uganda´ II. Strategic Objective a. To meet the energy needs of Uganda's population for social and economic development in an environmentally sustainable manner b. To use the country's oil and gas resources to contribute to early achievement of poverty eradication and create lasting value to society c. To develop the mineral sector for it to contribute significantly to sustainable national economic and social growth III. Major Achievements in 2018/19 ENERGY PLANNING MANAGEMENT AND INFRASTRUCTURE DEVELOPMENT Karuma HPP (600MW) physical progress was as at 89% as at 15th February 2019; Isimba HPP (183MW) final commissioning tests have been done and is already delivering power to the grid. The official commissioning is expected on 21st March 2019; Agago ±Achwa (42MW): The plant is undergoing final commissioning test. Electricity Transmission Projects: The following transmission projects were completed: Kawanda-Masaka T-Line 220kV, 137km line; Kawanda and Masaka substations; Nkenda-Fort Portal -Hoima 220kV, 226km line and associated Substations; Mbarara-Nkenda 132kV 160km; and the Isimba- Bujagali Interconnection project132kV, 41km line, Mbarara-Mirama 220kV, 65km line. The following transmission lines -

Nyakahita-Ibanda-Kamwenge Road Upgrading Project

ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSENT SUMMARY Project Name: Road Sector Support Project 3: Nyakahita-Ibanda-Kamwenge Road Upgrading Project Country: Uganda Project Number: P-UG-DB0-020 1.0 Introduction Following a request by the Government of Uganda to the African Development Bank (AfDB) to finance the upgrading of the Nyakahita-Ibanda-Kamwenge road from gravel to bitumen standard an Environmental and Social Impact Assessment had to be carried out by the project proponent (Uganda National Roads Authority – UNRA). UNRA in contracted the services of Consulting Engineering Services (India) Private Limited in Association with KOM Consult Limited to carry out the ESIA which was completed in January 2009, and the National Environment Management Authority (NEMA) reviewed and approved the report on 13 March 2009. The ESIA Summary is being posted on the AfDB website for pubic information as is required by the Bank policy on public disclosure. The summary covers: i) Project description and justification, ii) Policy legal and administrative framework, iii) Description of the project environment, iv) Project alternatives, v) potential impacts and mitigation/enhancement measures, vi) environmental and social management plan, vii) monitoring program, viii) public consultations and disclosure, ix) ESMP and cost estimates, x) conclusion and recommendations, xi) reference and contacts, and xii) an annex “resettlement action plan” (RAP). 2.0 Project Description and Justification The project is in Western Uganda and the project road traverses three districts of Kirihura, Ibanda and Kamwenge which have an estimated population of 0.7 million people. The rest of the road continues to Fort Portal in Kabalore district. The project shall upgrade the road from gravel to paved standards and is 153 km long and it has a 6 m wide carriageway and 1.5 m shoulders on either side. -

Legend " Wanseko " 159 !

CONSTITUENT MAP FOR UGANDA_ELECTORAL AREAS 2016 CONSTITUENT MAP FOR UGANDA GAZETTED ELECTORAL AREAS FOR 2016 GENERAL ELECTIONS CODE CONSTITUENCY CODE CONSTITUENCY CODE CONSTITUENCY CODE CONSTITUENCY 266 LAMWO CTY 51 TOROMA CTY 101 BULAMOGI CTY 154 ERUTR CTY NORTH 165 KOBOKO MC 52 KABERAMAIDO CTY 102 KIGULU CTY SOUTH 155 DOKOLO SOUTH CTY Pirre 1 BUSIRO CTY EST 53 SERERE CTY 103 KIGULU CTY NORTH 156 DOKOLO NORTH CTY !. Agoro 2 BUSIRO CTY NORTH 54 KASILO CTY 104 IGANGA MC 157 MOROTO CTY !. 58 3 BUSIRO CTY SOUTH 55 KACHUMBALU CTY 105 BUGWERI CTY 158 AJURI CTY SOUTH SUDAN Morungole 4 KYADDONDO CTY EST 56 BUKEDEA CTY 106 BUNYA CTY EST 159 KOLE SOUTH CTY Metuli Lotuturu !. !. Kimion 5 KYADDONDO CTY NORTH 57 DODOTH WEST CTY 107 BUNYA CTY SOUTH 160 KOLE NORTH CTY !. "57 !. 6 KIIRA MC 58 DODOTH EST CTY 108 BUNYA CTY WEST 161 OYAM CTY SOUTH Apok !. 7 EBB MC 59 TEPETH CTY 109 BUNGOKHO CTY SOUTH 162 OYAM CTY NORTH 8 MUKONO CTY SOUTH 60 MOROTO MC 110 BUNGOKHO CTY NORTH 163 KOBOKO MC 173 " 9 MUKONO CTY NORTH 61 MATHENUKO CTY 111 MBALE MC 164 VURA CTY 180 Madi Opei Loitanit Midigo Kaabong 10 NAKIFUMA CTY 62 PIAN CTY 112 KABALE MC 165 UPPER MADI CTY NIMULE Lokung Paloga !. !. µ !. "!. 11 BUIKWE CTY WEST 63 CHEKWIL CTY 113 MITYANA CTY SOUTH 166 TEREGO EST CTY Dufile "!. !. LAMWO !. KAABONG 177 YUMBE Nimule " Akilok 12 BUIKWE CTY SOUTH 64 BAMBA CTY 114 MITYANA CTY NORTH 168 ARUA MC Rumogi MOYO !. !. Oraba Ludara !. " Karenga 13 BUIKWE CTY NORTH 65 BUGHENDERA CTY 115 BUSUJJU 169 LOWER MADI CTY !. -

Executive Summary

KARUMA HPP (600 MW) __________________________________________ EIPL Executive Summary Uganda is currently facing a huge electricity supply deficit; it has one of the world’s lowest levels of electricity development as well as the lowest per capita electricity consumption. Over 90 percent of the country's population is not connected to the national grid, much of the electricity network at present is poorly maintained and country the experiences frequent power cuts. According to the National Development Plan (NDP- 2010/11-2014) the present peak demand of Uganda is about 400 MW or more which has been growing at an annual rate of 8%, to meet this growth with demand about 20 MW of new generating capacity needs to be added each year. NDP further identifies that, current levels of electricity supply cannot support heavy industries limited generation capacity and corresponding limited transmission and distribution network as among other key constraints to the performance of the energy sector in the country. Given the large and growing gap between electricity supply and demand in Uganda, a number of electricity generation alternatives were explored under Rural Electrification Programme for next 20 years. Studies over various planning horizons were also examined and prioritized for the country under the Hydropower Master Plan. The conclusions from the evaluation of these generation alternatives reveals that large scale hydroelectric development is the most economical way forward for the country in the short-medium term. Therefore, to meet the growing electricity demand seven potential hydropower sites have been examined downstream of Bujagali Hydro Power Project (which is already under construction) over River Victoria Nile from Lake Victoria to Lake Albert as river is the primary hydrological resource available in country.