Lightening the Lode: a Guide to Responsible Large-Scale Mining

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contrasting Andean Attitudes Towards Foreign Direct Investment

9 | Global Societies Journal, Issue 1, 2013 So Close Yet So Far: Contrasting Andean Attitudes towards Foreign Direct Investment By: Daniela Peinado ABSTRACT Should a developing nation embrace foreign direct investment, or are such decisions more likely to result in a dependency that inhibits growth in the long run? The recently elected presidents of neighboring countries Bolivia and Peru have opposing attitudes in this regard, despite their analogous reliance on mineral exports and predominantly indigenous populations. I closely examine the impact of two lucrative mines—both in production for over one hundred years, privatized around the turn of the last century, and most recently owned by Swiss company Glencore. I find that Morales’s choice to renationalize the mine in Bolivia is justified based on the perceived impact of foreign involvement, the desires of his constituents, and his overwhelming concern for the environment. However, though the country has made significant financial gains thus far, it is still too soon to fully realize the repercussions of his decision. On the other hand, as Peru enjoys a relatively prosperous economy, even a narrowly focused case study illustrates the merits and downfalls of neoliberal policies in Latin America. Keywords: political economy, nationalize, privatize, foreign direct investment, development, resources, populist, public opinion, neoliberal policies INTRODUCTION Foreign direct investment is a divisive topic in the study of international political economy, and especially important as the world continues to grow interconnected. Opponents contend it is exploitative and leads to dependant development, while proponents suggest it might even be essential for economic growth, providing capital, technology, and employment. -

Petrology of Ore Deposits

Petrology of Ore Deposits An Introduction to Economic Geology Introductory Definitions Ore: a metalliferous mineral, or aggregate mixed with gangue that can me mined for a profit Gangue: associated minerals in ore deposit that have little or no value. Protore: initial non-economic concentration of metalliferous minerals that may be economic if altered by weathering (Supergene enrichment) or hydrothermal alteration Economic Considerations Grade: the concentration of a metal in an ore body is usually expressed as a weight % or ppm. The process of determining the grade is termed “assaying” Cut-off grade: after all economic and political considerations are weighed this is the lowest permissible grade that will mined. This may change over time. Example Economic Trends Economy of Scale As ore deposits are mined the high-grade zones are developed first leaving low-grade ores for the future with hopefully better technology Since mining proceeds to progressively lower grades the scale of mining increases because the amount of tonnage processed increases to remove the same amount of metal Outputs of 40,000 metric tons per day are not uncommon Near-surface open pit mines are inherently cheaper than underground mines Other factors important to mining costs include transportation, labor, power, equipment and taxation costs Classification of Ore bodies Proved ore: ore body is so thoroughly studied and understood that we can be certain of its geometry, average grade, tonnage yield, etc. Probable ore: ore body is somewhat delineated by surface mapping and some drilling. The geologists is reasonably sure of geometry and average grade. Possible Ore: outside exploration zones the geologist may speculate that the body extends some distance outside the probable zone but this is not supported by direct mapping or drilling. -

Ÿþm Icrosoft W

Copernic Agent Search Results Search: explosion deep mine (All the words) Found: 3464 result(s) on _Full.Search Date: 7/23/2010 10:40:53 AM 1. History Channel Presents: NOSTRADAMUS: 2012 Dec 31, 2008 ... I really want to get these into deeps space because who knows whats ..... what created the molecules or atoms that caused the explosion “big .... A friend of mine emailed me. He asked me if I had see the show on the ... http://ufos.about.com/b/2008/12/31/history-channel-presents-nostradamus-2012.htm 95% 2. Current Netlore - Internet hoaxes, rumors, etc. - A to Z Index, cont. Cell Phones Cause Gas Station Explosions Still unsubstantiated. .... 8-month-old Delaney Parrish, who was seriously burned by hot oil from a Fry Daddy deep fryer in 2001. ..... who lost his leg in a land mine explosion in Afghanistan. ... http://urbanlegends.about.com/library/blxatoz2.htm 94% 3. North Carolina Collection-This Month in North Carolina History - Carolina Coal Company Mine Explosion Sep 2009 - ...Carolina Coal Company Mine Explosion, Coal Glen, North...1925, a massive explosion shook the town of...blast came from the Deep River Coal Field...underground. The explosion, probably touched...descent into the mine on May 31st. Seven... http://www.lib.unc.edu/ncc/ref/nchistory/may2005/index.html 94% 4. Safety comes first at Sugar Creek limestone mine 2010/07/17 The descent takes perhaps 90 seconds. Daylight blinks out, and the speed of the steel cages descent accelerates. Soon, the ears pop slightly. http://www.kansascity.com/2010/07/16/2084075/safety-comes-first-at-sugar-creek.html 94% 5. -

FORUM: Sixth Committee of the General Assembly (Legal)

FORUM: Sixth Committee of the General Assembly (Legal) QUESTION OF: Establishing guidelines to ensure better and safer working conditions in quar- ries and mines STUDENT OFFICER: Jacqueline Schnell POSITION: Main Chair INTRODUCTION "Every coal miner I talked to had, in his history, at least one story of a cave-in. 'Yeah, he got covered up,' is a way coal miners refer to fathers and brothers and sons who got buried alive.“ ~ Jeanne Marie Laskas As stated in the quote above, every miner knows the risks it takes to work in such an industry. Mining has always been a risky occupation, es- pecially in developing na- tions and countries with lax safety standards. Still today, thousands of miners die from mining accidents each year, especially in the pro- cess of coal and hard rock mining, as can be seen in the diagram below. Although the number of deadly Source: see: IX. Useful Links and Sources: XI. Statistics to mine accidents accidents is declining, any fatal accident should still be considered a tragedy, and definitely must be prevented in advance. It seems totally irresponsible and reprehensible that while technological improvements and stricter safety regulations have reduced coal mining related deaths, accidents are still so common, most of them occurring in developing countries. Page 1 of 14 AMUN 2019 – Research Report for the 6th committee Sadly, striving for quick profits in lieu of safety considerations led to several of these tremendous calamities in the near past. Only in Chinese coal mines an average of 13 miners are killed a day. The Benxihu colliery disaster, which is believed to be the worst coal mining disaster in human history, took place in China, as well, and cost 1,549 humans their lives. -

El Clúster Productivo Del Cobre: Retos Para La Sostenibilidad

Dirección Nacional de Prospectiva y Estudios Estratégicos EL CLÚSTER PRODUCTIVO DEL COBRE: RETOS PARA LA SOSTENIBILIDAD Documento de trabajo Actualizado al 21 de diciembre del 2020 El clúster productivo del cobre: retos para la sostenibilidad Javier Abugattás Presidente del Consejo Directivo del CEPLAN Centro Nacional de Planeamiento Estratégico Bruno Barletti Director Ejecutivo del CEPLAN Jordy Vilchez Astucuri Director Nacional de Prospectiva y Estudios Estratégicos Equipo técnico: Erika Celiz Ignacio, Marco Francisco Torres, Karin Rivera Miranda, Gustavo Rondón Ramirez. Editado por: Centro Nacional de Planeamiento Estratégico Av. Canaval y Moreyra 480, piso 11 San Isidro, Lima, Perú (51-1) 211-7800 [email protected] www.ceplan.gob.pe © Derechos reservados Primera edición, junio de 2020 2 Tabla de contenido Resumen ejecutivo .............................................................................................................. 5 I. Introducción ..................................................................................................................... 6 II. Marco metodológico ........................................................................................................ 7 2.1. Marco de Medios de Vida Sostenibles .................................................................................. 7 2.1.1. Principios ............................................................................................................................ 7 2.1.2. Elementos que conforman el marco de Medios de Vida Sostenibles -

Principles of Extractive Metallurgy Lectures Note

PRINCIPLES OF EXTRACTIVE METALLURGY B.TECH, 3RD SEMESTER LECTURES NOTE BY SAGAR NAYAK DR. KALI CHARAN SABAT DEPARTMENT OF METALLURGICAL AND MATERIALS ENGINEERING PARALA MAHARAJA ENGINEERING COLLEGE, BERHAMPUR DISCLAIMER This document does not claim any originality and cannot be used as a substitute for prescribed textbooks. The information presented here is merely a collection by the author for their respective teaching assignments as an additional tool for the teaching-learning process. Various sources as mentioned at the reference of the document as well as freely available material from internet were consulted for preparing this document. The ownership of the information lies with the respective author or institutions. Further, this document is not intended to be used for commercial purpose and the faculty is not accountable for any issues, legal or otherwise, arising out of use of this document. The committee faculty members make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this document and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. BPUT SYLLABUS PRINCIPLES OF EXTRACTIVE METALLURGY (3-1-0) MODULE I (14 HOURS) Unit processes in Pyro metallurgy: Calcination and roasting, sintering, smelting, converting, reduction, smelting-reduction, Metallothermic and hydrogen reduction; distillation and other physical and chemical refining methods: Fire refining, Zone refining, Liquation and Cupellation. Small problems related to pyro metallurgy. MODULE II (14 HOURS) Unit processes in Hydrometallurgy: Leaching practice: In situ leaching, Dump and heap leaching, Percolation leaching, Agitation leaching, Purification of leach liquor, Kinetics of Leaching; Bio- leaching: Recovery of metals from Leach liquor by Solvent Extraction, Ion exchange , Precipitation and Cementation process. -

News Release ______

News Release _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: Contact: Darren Rogers Senior Director, Communications & Media Services Churchill Downs Racetrack (502) 636-4461 (office) (502) 345-1030 (mobile) [email protected] SIR TRUEBADOUR GIVES ASMUSSEN HIS RECORD-EQUALING FIFTH BASHFORD MANOR LOUISVILLE, Ky. (Saturday, June 30, 2018) – Whispering Oaks Farm LLC ’s Sir Truebadour led every step of the way in Saturday’s 117th running of the $100,000 Bashford Manor (Grade III) on closing day at Churchill Downs’ 38-day Spring Meet to beat Mr Chocolate Chip by two lengths and give Hall of Fame trainer Steve Asmussen an impressive fifth win in the nation’s first graded stakes race for 2-year-olds. Ridden by Ricardo Santana Jr., Sir Truebadour, who was sent to post as the hot 3-2 favorite, ran six furlongs over a fast main track in 1:12.77 – the slowest of 19 Bashford Manor renewals at the six-furlong distance. Sir Truebadour was leg weary late in the stretch but had a jump on his 11 rivals after breaking alertly from post 4. He battled from the inside with 48-1 longshot The Song of John and Mr. Granite for the early lead and ran the first quarter mile in a swift :21.35. The Song of John got within a half-length of Sir Truebadour at the top of the stretch but the winner spurted clear after a half mile in :45.63 and drew clear midway down the lane, and had enough to hold on comfortably. “Steve and his team did a great job with this horse,” Santana said. -

Hard-Rock Mining, Labor Unions, and Irish Nationalism in the Mountain West and Idaho, 1850-1900

UNPOLISHED EMERALDS IN THE GEM STATE: HARD-ROCK MINING, LABOR UNIONS AND IRISH NATIONALISM IN THE MOUNTAIN WEST AND IDAHO, 1850-1900 by Victor D. Higgins A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Boise State University August 2017 © 2017 Victor D. Higgins ALL RIGHTS RESERVED BOISE STATE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE COLLEGE DEFENSE COMMITTEE AND FINAL READING APPROVALS of the thesis submitted by Victor D. Higgins Thesis Title: Unpolished Emeralds in the Gem State: Hard-rock Mining, Labor Unions, and Irish Nationalism in the Mountain West and Idaho, 1850-1900 Date of Final Oral Examination: 16 June 2017 The following individuals read and discussed the thesis submitted by student Victor D. Higgins, and they evaluated his presentation and response to questions during the final oral examination. They found that the student passed the final oral examination. John Bieter, Ph.D. Chair, Supervisory Committee Jill K. Gill, Ph.D. Member, Supervisory Committee Raymond J. Krohn, Ph.D. Member, Supervisory Committee The final reading approval of the thesis was granted by John Bieter, Ph.D., Chair of the Supervisory Committee. The thesis was approved by the Graduate College. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author appreciates all the assistance rendered by Boise State University faculty and staff, and the university’s Basque Studies Program. Also, the Idaho Military Museum, the Idaho State Archives, the Northwest Museum of Arts and Culture, and the Wallace District Mining Museum, all of whom helped immensely with research. And of course, Hunnybunny for all her support and patience. iv ABSTRACT Irish immigration to the United States, extant since the 1600s, exponentially increased during the Irish Great Famine of 1845-52. -

Evaluation of Scale-Up Model for Flotation with Kristineberg Ore

Evaluation of Scale-up Model for Flotation with Kristineberg Ore Adam Isaksson Chemical Engineering, master's level 2018 Luleå University of Technology Department of Civil, Environmental and Natural Resources Engineering Evaluation of Scale-up Model for Flotation with Kristineberg Ore Adam Isaksson 2018 For degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Luleå University of Technology Department of Civil, Environmental and Natural Resources Engineering Division of Minerals and Metallurgical Engineering Printed by Luleå University of Technology, Graphic Production 2018 Luleå 2018 www.ltu.se Preface As you may have figured out by now, this thesis is all about mineral processing and the extraction of metals. It was written as part of my studies at Luleå University of Technology, for a master’s degree in Chemical Engineering with specialisation Mineral and Metal Winning. There are many people I would like to thank for helping me out during all these years. First of all, my thanks go to supervisors Bertil Pålsson and Lisa Malm for the guidance in this project. Iris Wunderlich had a paramount role during sampling and has kindly delivered me data to this report, which would not have been finished without her support. I would also like to thank Boliden Mineral AB as a company. Partly for giving me the chance to write this thesis in the first place, but also for supporting us students during our years at LTU. Speaking of which, thanks to Olle Bertilsson for reading the report and giving me feedback. The people at the TMP laboratory deserves another mention. I am also very grateful for the financial support and generous scholarships from Jernkontoret these five years. -

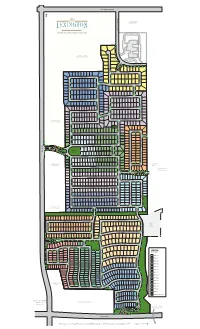

Lex Mastermap Handout

ELDORADO PARKWAY M A MM *ZONED FUTURE O TH LIGHT RETAIL C A VE LANE MASTER PLANNED GATED COMMUNITY *ZONED FUTURE RETAIL/MULTI-FAMILY M A J E MAMMOTH CAVE LANE S T T IN I C O P P L I R A I N R E C N E O C D I R C L ORB DRIVE E A R I S T MACBETH AVENUE I D E S D R I V E M SPOKANE WAY D ANUEL STRE ARK S G I A C T O AR LANE CARRY BACK LANE 7 M O E L T A N E 8 NORTHERN DANCER WAY GALLAHADION WAY GRINDS FUN N T Y CIDE ONE THUNDER GULCH WAY M C ANOR OU BROKERS TIP LANE R T M ANUEL STRE E PLAC RAL DMI WAR A E T DAY STAR WAY *ZONED FUTURE 3 LIGHT COMMERCIAL BOLD FORBES STREET FERDINAND VIEW LEON PONDER LANE A TUS LANE SEATTLE SLEW STREET GRAHAM AVENUE WINTE R GREEN DRIVE C OIT SECRETARIAT BOULEVARD C OUNT R O TURF DRIVE AD S AMENITY M A CENTER R T Y JONES STRE STRIKE GOLD BOULEVARD E T L 5 2 UC K Y DEBONAIR LANE C 1 A Yucca Ridge *ZONED FUTURE V FLYING EBONY STREET A LIGHT RETAIL L C Park ADE DRIVE AFFIRMED AVENUE Independence High School SUTHERLAND LANE AZRA TRAIL OMAHA DRIVE BOLD VENTURE AVENUE C L ONQUIS UC O XBOW K Y DEBONAIR LANE C 4 T A ADOR V A A VENUE L C ADE DRIVE WHIRLAWAY DRIVE C OU R 9T IRON LIEGE DRIVE *ZONED FUTURE IRON LIEGE DRIVE LIGHT COMMERCIAL 6 A M EMPIRE MAKER ROAD E RISEN STAR ROAD R I BUBBLING OVER C W A AR EMBLEM PL N Future P H City A R O Park A H D R A O R CE I AD V E DUST COMMANDER COURT FO DETERMINE DRIVE R W ARD P 14 ASS CI SPECTACULAR BID STREET REAL QUI R CLE E T R TIM TAM CIRCLE D . -

Celso Furtado As 'Romantic Economist'from Brazil's Sertão

Brazilian Journal of Political Economy, vol 39 , nº 4 (157), pp 658-674, October-December/2019 Celso Furtado as ‘Romantic Economist’ from Brazil’s Sertão Celso Furtado como Economista Romântico do Sertão JONAS RAMA* JOHN BATTAILE HALL** RESUMO: Em The Romantic Economist (2009), Richard Bronk lamenta que o pensamento iluminista tenha dominado a economia durante sua formação como ciência. O “Movimen- to Romântico” seria um contraponto, mas foi mantido distante. A economia abraçou a cen- tralidade da racionalidade e preceitos iluministas, tornando-se uma “física-social”. Desde então, as características humanas como sentimento, imaginação e criatividade são evitadas. Embora Bronk não identifique um economista “romântico” de carne e osso, nossa pesquisa busca estabelecer Celso Furtado como um. Profundamente influenciado por sua sensibili- dade e raízes, Furtado fez uso de uma metáfora orgânica – o sertão nordestino – em seu entendimento de complexos processos de desenvolvimento. PALAVRAS-CHAVE: Brasil; Celso Furtado; Richard Bronk; movimento romântico; sertão. ABSTRACT: In The Romantic Economist (2009), Richard Bronk laments that Enlighten- ment thinking dominated Economics during its formation as a science. As counterpoint, the ‘Romantic Movement’ had much to offer but remained peripheral. Consequently Economics embraced the centrality of rationality and other Enlightenment precepts, leading to a ‘social- physics’. Meanwhile human characteristics such; as sentiments, imagination and creativ- ity were eschewed. While Bronk fails to identify an in-the-flesh ‘Romantic Economist’, our inquiry seeks to establish that indeed Celso Furtado qualifies. Profoundly influenced by his sensitivities and attachment to place, Furtado relies upon an organic metaphor – o sertão nordestino – for insights into complex developmental processes. KEYWORDS: Brazil; Celso Furtado; Richard Bronk; romantic movement; sertão. -

Principles of Geochemical Prospecting

Principles of Geochemical Prospecting GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 1000-F CONTRIBUTIONS TO GEOCHEMICAL PROSPECTING FOR MINERALS PRINCIPLES OF GEOCHEMICAL PROSPECTING By H. E. HAWKES ABSTRACT Geochemical prospecting for minerals includes any method of mineral exploration based on systematic measurement of the chemical properties of a naturally occurring material. The purpose of the measurements is the location of geochemical anomalies or of areas where the chemical pattern indicates the presence of ore in the vicinity. Anomalies may be formed either at depth by igneous and metamorphic processes or at the earth's surface by agents of weathering, erosion, and surficial transportation. Geochemical anomalies of deep-seated origin primary anomalies may result from (1) apparent local variation in the original composition of the earth's crust, defining a distinctive "geochemical province" especially favor able for the occurrence of ore, (2) impregnation of rocks by mineralizing fluids related to ore formation, and (3) dispersion of volatile elements transported in gaseous form. Anomalies of surficial origin-^secondary anomalies take the form either of residual materials from weathering of rocks and ores in place or of material dispersed from the ore deposit by gravity, moving water, or glacial ice. The mobility of an element, or tendency for it to migrate in the.surficial environment, determines the characteristics of the geochemical anomalies it can form. Water is the principal transporting agency for the products of weathering. Mobility is, therefore, closely related to the tendency of an element to be stable in water-soluble form. The chemical factors affecting the mobility of elements include hydrogen-ion concentration, solubility of salts, coprecipitation, sorption, oxidation potential, and the formation of complexes and colloidal solutions.