Doolittle Raid

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

H1 Toryjournal

TheWittenberg H1 toryJournal Wittenberg University • Springfield, Ohio Volume XXXII Spring2003 From the Editors: Greetings from the editors of the WittenbergUniversity History Journal. As you may notice, the format for this year's publication has changed from previous issues. We hope that this change is the first step in redefining the journal by making the physical publication even more professional. The within articles are, as always, excellent examples of what students here at Wittenberg are writing, and we hope that you wili enjoy reading them. A very special thanks is due to Tom and Tina Lagos, the Admission Office at Wittenberg and the Wittenberg History Club for their generous donations. Without their financial assistance, this publication would not have been possible. We would also like to thank all those involved in making this journal possible and congratulations to all the writers on creating such superior works. Mark Huber, Mandy Oleson and Dustin Plummer The Wittenberg University History Journal 2002-03 Editorial Staff '04, '03 Co-editors .......................... Mark Huber Mandy Oleson and Dustin Plummet '03 Editorial Staff ................. Erica Fornari '04, Greer Illingworth '05 Nicole Roberts '03 and Rebecca Roush '03 Advisor ......................................................... Dr. Jim Huffman The Hartje Papers The Martha and Robert G. Hartje Award is presented annually to a Senior in the spring semester. The History Department determines the five finalists who write a 600 to 800 word narrative essay dealing with a historical event or figure. The finalists must have at least a 2.7 grade point average and have completed at least six history courses. The winner is awarded $500 at a spring semester History Department colloquium and the winning paper is included in the HistoryJournal. -

Guide to the Doolittle Tokyo Raider Association Papers (1947

Guide to the Doolittle Tokyo Raider Association Papers (1947 - ) 26 linear feet Accession Number: 54-06 Collection Number: H54-06 Collection Dates: 1931 - Bulk Dates: 1942 - 2005 Prepared by Thomas J. Allen CITATION: The Doolittle Tokyo Raiders Association Papers, Box number, Folder number, History of Aviation Collection, Special Collections Department, McDermott Library, The University of Texas at Dallas. Special Collections Department McDermott Library, The University of Texas at Dallas Contents Historical Sketch ................................................................................................................. 3 Sources ................................................................................................................................ 3 Additional Sources .............................................................................................................. 3 Series Description ............................................................................................................... 4 Scope and Content Note...................................................................................................... 5 Collection Note ................................................................................................................... 8 Provenance Statement ......................................................................................................... 8 Literary Rights Statement ................................................................................................... 8 2 -

Another Perspective on Pearl Harbor, Containing an Epic Story with Powerful Characters Life of Mitsuo Fuchida to Be Unveiled in Upcoming Book, Possible Film

Another perspective on Pearl Harbor, containing an epic story with powerful characters Life of Mitsuo Fuchida to be unveiled in upcoming book, possible film Donald L. Gilleland, retired in Suntree, served 30 years in the military and is former corporate director of public affairs for General Dynamics Corp. Saturday, December 7, 2013 On Dec. 8, 1941, as part of a declaration of war, President Franklin Roosevelt said, Dec. 7 “ is a date which will live in infamy ...” Since then, many books have been written about the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, but most of them are strictly from an American perspective. “Wounded Tiger,” a book about to be published, will give Americans a somewhat different view, because much of the story is told from a Japanese perspective. Written by T. Martin Bennett, “Wounded Tiger” is a historical nonfiction novel based on the life of Mitsuo Fuchida, the Japanese pilot who led the attack on Pearl Harbor. Fuchida was a Japanese hero because of his aviation skills in the war with China from 1937 to 1941. Because of his record in the Chinese theater, he was picked to plan and lead the attack on Pearl Harbor, after which he was promoted and given a personal audience with Emperor Hirohito. Following the war, Fuchida met Staff Sgt. Jacob DeShazer, an American member of the Doolittle Raiders who had spent most of the war brutalized in a Japanese prisoner of war camp, In this photo provided by the U.S. Navy, a Navy launch pulls up to the before becoming a Christian blazing USS West Virginia to rescue a sailor, Dec. -

Japan's Pacific Campaign

2 Japan’s Pacific Campaign MAIN IDEA WHY IT MATTERS NOW TERMS & NAMES EMPIRE BUILDING Japan World War II established the • Isoroku •Douglas attacked Pearl Harbor in Hawaii United States as a leading player Yamamoto MacArthur and brought the United States in international affairs. •Pearl Harbor • Battle of into World War II. • Battle of Guadalcanal Midway SETTING THE STAGE Like Hitler, Japan’s military leaders also had dreams of empire. Japan’s expansion had begun in 1931. That year, Japanese troops took over Manchuria in northeastern China. Six years later, Japanese armies swept into the heartland of China. They expected quick victory. Chinese resistance, however, caused the war to drag on. This placed a strain on Japan’s economy. To increase their resources, Japanese leaders looked toward the rich European colonies of Southeast Asia. Surprise Attack on Pearl Harbor TAKING NOTES Recognizing Effects By October 1940, Americans had cracked one of the codes that the Japanese Use a chart to identify used in sending secret messages. Therefore, they were well aware of Japanese the effects of four major plans for Southeast Asia. If Japan conquered European colonies there, it could events of the war in the also threaten the American-controlled Philippine Islands and Guam. To stop the Pacific between 1941 and 1943. Japanese advance, the U.S. government sent aid to strengthen Chinese resistance. And when the Japanese overran French Indochina—Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos—in July 1941, Roosevelt cut off oil shipments to Japan. Event Effect Despite an oil shortage, the Japanese continued their conquests. They hoped to catch the European colonial powers and the United States by surprise. -

Additional Historic Information the Doolittle Raid (Hornet CV-8) Compiled and Written by Museum Historian Bob Fish

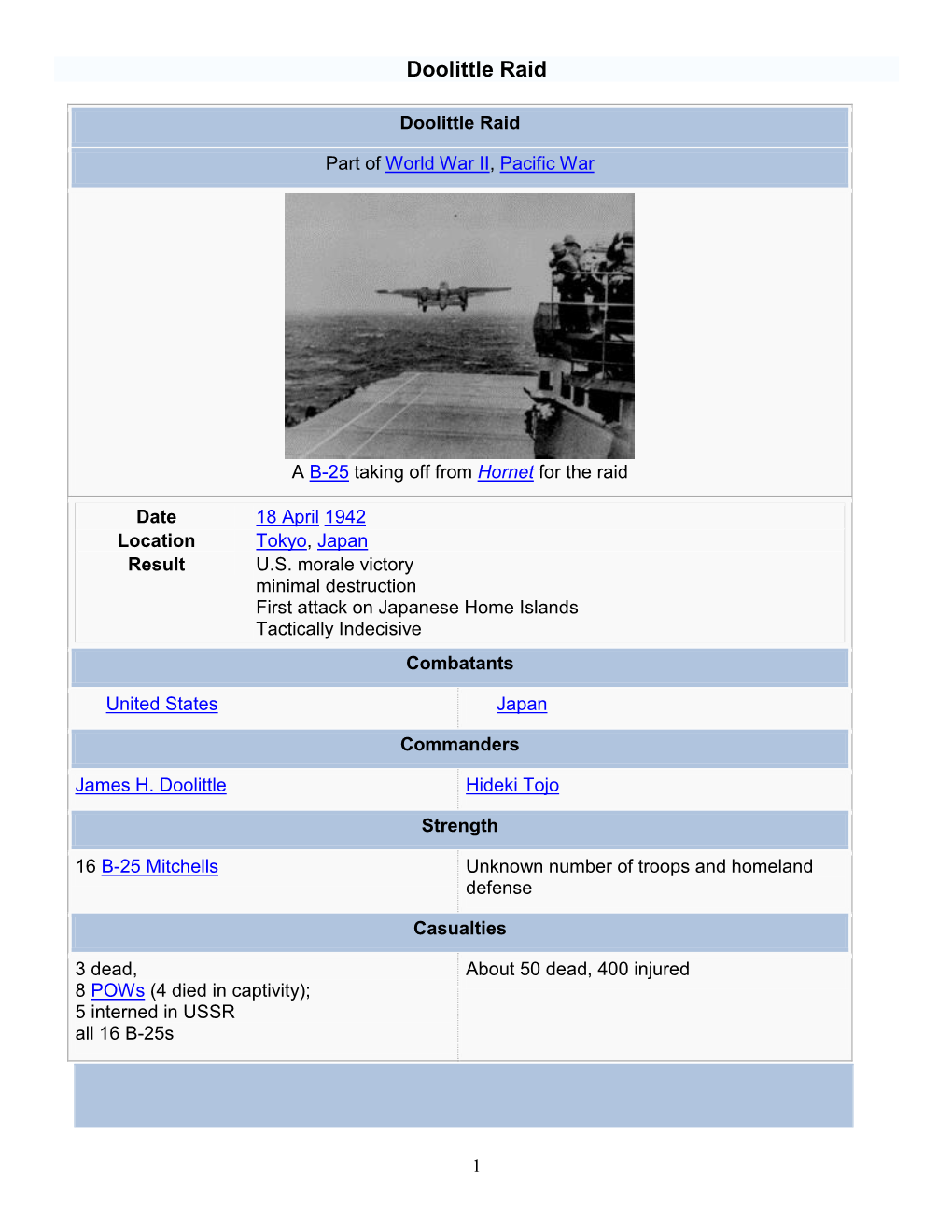

USS Hornet Sea, Air & Space Museum Additional Historic Information The Doolittle Raid (Hornet CV-8) Compiled and Written by Museum Historian Bob Fish AMERICA STRIKES BACK The Doolittle Raid of April 18, 1942 was the first U.S. air raid to strike the Japanese home islands during WWII. The mission is notable in that it was the only operation in which U.S. Army Air Forces bombers were launched from an aircraft carrier into combat. The raid demonstrated how vulnerable the Japanese home islands were to air attack just four months after their surprise attack on Pearl Harbor. While the damage inflicted was slight, the raid significantly boosted American morale while setting in motion a chain of Japanese military events that were disastrous for their long-term war effort. Planning & Preparation Immediately after the Pearl Harbor attack, President Roosevelt tasked senior U.S. military commanders with finding a suitable response to assuage the public outrage. Unfortunately, it turned out to be a difficult assignment. The Army Air Forces had no bases in Asia close enough to allow their bombers to attack Japan. At the same time, the Navy had no airplanes with the range and munitions capacity to do meaningful damage without risking the few ships left in the Pacific Fleet. In early January of 1942, Captain Francis Low1, a submariner on CNO Admiral Ernest King’s staff, visited Norfolk, VA to review the Navy’s newest aircraft carrier, USS Hornet CV-8. During this visit, he realized that Army medium-range bombers might be successfully launched from an aircraft carrier. -

Cincinnati's Doolittle Raider at War

Queen City Heritage Thomas C. Griffin, a resident of Cincinnati for over forty years, participated in the first bombing raid on Japan in World War II, the now leg- endary Doolittle raid. (CHS Photograph Collection) Winter 1992 Navigating from Shangri-La Navigating from Shangri- La: Cincinnati's Doolittle Raider at War Kevin C. McHugh served as Cincinnati's oral historian for "one of America's biggest gambles"5 of World War II, the now legendary Doolittle Raid on Japan. A soft-spoken man, Mr. Griffin Over a half century ago on April 18, 1942, characteristically downplays his part in the first bombing the Cincinnati Enquirer reported: "Washington, April 18 raid on Japan: "[It] just caught the fancy of the American — (AP) — The War and Navy Departments had no confir- people. A lot of people had a lot worse assignments."6 mation immediately on the Japanese announcement of the Nevertheless, he has shared his wartime experiences with bombing of Tokyo."1 Questions had been raised when Cincinnati and the country, both in speaking engagements Tokyo radio, monitored by UPI in San Francisco, had sud- and in print. In 1962 to celebrate the twentieth anniversary denly gone off the air and then had interrupted program- of the historic mission, the Cincinnati Enquirer highlight- ming for a news "flash": ed Mr. Griffin's recollections in an article that began, Enemy bombers appeared over Tokyo for the "Bomber Strike from Carrier Recalled."7 For the fiftieth first time since the outbreak of the current war of Greater anniversary in 1992, the Cincinnati Post shared his adven- East Asia. -

Tokyo Bay the AAF in the Asiatic-Pacific Theater

The U.S. Army Air Forces in World War II The High Road to Tokyo Bay The AAF in the Asiatic-Pacific Theater Daniel Haulman Air Force Historical Research Agency DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT A Approved for Public Release Distribution Unlimited "'Aý-Iiefor Air Force History 1993 20050429 028 The High Road to Tokyo Bay In early 1942, Japanese military forces dominated a significant portion of the earth's surface, stretching from the Indian Ocean to the Bering Sea and from Manchuria to the Coral Sea. Just three years later, Japan surrendered, having lost most of its vast domain. Coordinated action by Allied air, naval, and ground forces attained the victory. Air power, both land- and carrier-based, played a dominant role. Understanding the Army Air Forces' role in the Asiatic-Pacific theater requires examining the con- text of Allied strategy, American air and naval operations, and ground campaigns. Without the surface conquests by soldiers and sailors, AAF fliers would have lacked bases close enough to enemy targets for effective raids. Yet, without Allied air power, these surface victories would have been impossible. The High Road to Tokyo Bay concentrates on the Army Air Forces' tactical operations in Asia and the Pacific areas during World War II. A subsequent pamphlet will cover the strategic bombardment of Japan. REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704-0188 The public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. -

The Eagle's Webbed Feet

The Eagle’s Webbed Feet The Eagle’s Webbed Feet •A Maritime History of the United States A Maritime History of the United States A Maritime History of the Uniteds The Second World War “Scratch one flattop!” “Damn it Captain, they’re getting away!” Pearl Harbor • China is the real bone of contention between the US and Japan • May 1941, Roosevelt orders the fleet to remain in Pearl Harbor • July 1941 – Oil imports to Japan halted • Japanese decision to go southeast for resources • The Soviet-Japanese Border Wars (1932-1939) o Battles of Khalkhin Gol (Nomonhan) (May-Sept 1939) o Neutrality Pact (April 1941) • The Philippines is the real target of the Pearl Harbor attack • Mahan’s influence on the IJN. “If you attack us, we will break your empire; before we are through with you …. we will crush you.” Admiral Stark (CNO) to Ambassador Nomura (Nov 1941) • What were the Japanese thinking? (Compromise Peace) Pearl Harbor (2) • Destroyed or severely damaged 8 battleships, 10 cruisers/destroyers, 230 aircraft, & killed 2400 men. Cost was 29 planes, 5 midget subs. • A “short war” meant they could ignore fuel depots, repair facilities and the submarine base. • Their air superiority meant they could ignore the US carriers • War declared on Japan the next day • On December 11th Germany declared war on the US (???) • One of the two stupidest decisions of World War Two USS Arizona USS Shaw War in the Atlantic • The US Navy’s role in the Atlantic War was: • The U-Boat War (Priority #1) • Safely convoying troops, equipment, and supplies • Destroy the U-Boat fleet • Conduct amphibious operations of Army forces • Because of Pearl Harbor, the Navy reluctantly supported the “Germany First” policy envisioned in Rainbow Five but it did not really believe in it. -

Picturing the War in the Pacific a Visual Time Line

LESSON PLAN: Picturing the War in the Pacific A Visual Time Line (National Archives and Records Administration, WC 1221.) INTRODUCTION By analyzing photographs and building a time line, students will be able to identify, discuss, and analyze the major events of World War II in the Pacific. First, students must match iconic images from the war in the Pacific with their captions. Then, they will place each image and caption in the correct chronological order to build a comprehensive time line of the war in the Pacific from the Japanese invasion of Manchuria to their surrender aboard the USS Missouri. Students will view the raising of the American flag on Mount Suribachi, look for a kamikaze attack on a US aircraft carrier, and identify the first Navajo code talkers sworn into the US Marine Corps. OBJECTIVES • By analyzing photographs and building a time line, students will be able to identify, discuss, and analyze the major events of World War II in the Pacific. • Students will also be able to identify the temporal structure of a historical narrative. GRADE LEVEL 7–12 TIME REQUIREMENT 1 class period MATERIALS • This lesson plan uses photographs and date and caption strips that are included as inserts with the printed guide and online at ww2classroom.org. • You may also need string and clothespins for this lesson. ONLINE RESOURCES ww2classroom.org The photographs, datelines, and captions used in this lesson are available online. LESSON PLAN PICTURING THE WAR IN THE PACIFIC The War in the Pacific 93 TEACHER STANDARDS COMMON CORE STANDARDS CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.SL.9-10.4 Present information, findings, and supporting evidence clearly, concisely, and logically such that listeners can follow the line of reasoning and the organization, development, substance, and style are appropriate to purpose, audience, and task. -

Commander of the Attack on Pearl Harbor

Mitsuo Fuchida Commander of the attack on Pearl Harbor Sunday Morning in Pearl Harbor The date was December 7, 1941. At approximately 7:49 a.m. Commander Mitsuo Fuchida, 39, led a fleet of 360 Japanese fighter planes through the billowy clouds high above Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. He had one thought in mind—cripple the American enemy. As Fuchida and his forces zeroed in on the peaceful harbor, the commander reached for his microphone, smiled, and ordered, "All squadrons, plunge in to attack!" _________________________________________ "All squadrons, plunge in to attack!" __________________________________________ During the ensuing hours, a pounding fury swallowed up the quiet waters as, one by one, American battleships were hit and began tilting into the sea—succumbing to the surprise invasion. Fuchida’s fleet mercilessly bombed nearby airfields, dry docks, and barracks. And 3,622 U.S. military personnel were reported killed or missing, with more than 800 wounded. With the famous words, "Tora! Tora! Tora!" Commander Fuchida signaled over the radio waves to his Japanese generals that the attack had been made. "It was the most thrilling exploit of my career," Fuchida later stated. Meanwhile... That same morning, Sergeant Jacob DeShazer was on KP duty peeling potatoes at a U.S. army base in Oregon. When news of the attack on Pearl Harbor by the Japanese came over the loudspeaker, DeShazer became enraged and shouted, "The Japs are going to have to pay for this!" At that moment, intense hatred for the Japanese was born in young Jacob DeShazer’s heart, and it grew with every passing day. -

Jimmy Doolittle E Commander Behind the Legend

THE 17 DREW PER PA S Jimmy Doolittle e Commander behind the Legend Benjamin W. Bishop Lieutenant Colonel, USAF Air University Steven L. Kwast, Lieutenant General, Commander and President School of Advanced Air and Space Studies Thomas D. McCarthy, Colonel, Commandant and Dean AIR UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF ADVANCED AIR AND SPACE STUDIES Jimmy Doolittle The Commander behind the Legend Benjamin W. Bishop Lieutenant Colonel, USAF Drew Paper No. 17 Air University Press Air Force Research Institute Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama Project Editor Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Jerry Gantt Bishop, Benjamin W., 1975– Copy Editor Jimmy Doolittle, the commander behind the legend / Tammi K. Dacus Benjamin W. Bishop, Lieutenant Colonel, USAF. pages cm. — (Drew paper, ISSN 1941-3785 ; no. 17) Cover Art, Book Design, and Illustrations Includes bibliographical references. Daniel Armstrong ISBN 978-1-58566-245-6 Composition and Prepress Production 1. Doolittle, James Harold, 1896-1993—Military leadership. Michele D. Harrell 2. Generals—United States—Biography. 3. Command of Print Preparation and Distribution troops—Case studies. 4. United States. Army Air Forces. Air Diane Clark Force, 8th. 5. World War, 1939-1945—Aerial operations, Amer- ican. I. Title. UG626.2.D66B57 2014 940.54’4973092—dc23 2014035210 AIR FORCE RESEARCH INSTITUTE AIR UNIVERSITY PRESS Published by Air University Press in February 2015 ISBN: 978-1-58566-245-6 Director and Publisher ISSN: 1941-3785 Allen G. Peck Editor in Chief Oreste M. Johnson Managing Editor Demorah Hayes -

Doolittle Scenario 1

Enemy Coast Ahead The Doolittle Raid special aviation project no. 1 Jeremy White scenario book table of contents Introduction 1 Scenario 7: The Army Launches for Tokyo 19 Historical Scenarios (1-9) 3 Scenario 8: The Planned Launch 25 Scenario 1: Attack of the First Flight 5 Scenario 9: The Doolittle Raid 29 Scenario 1v: Attack of the First Flight (night) 7 Scenario 10: Special Aviation Project #1 33 Scenario 2: Attack of the Second Flight 9 Multi-Player Games 37 Scenario 3: Attack of the Third Flight 11 Credits 37 Scenario 4: Attack of the Fourth Flight 13 Squadron Roster 38 Scenario 5: Attack of the Fifth Flight 15 Squadron Log 39 Scenario 6: TNT Attacks 17 GMT Games, LLC P.O. Box 1308, Hanford, CA 93232-1308 www.GMTGames.com 1 Introduction There are ten scenarios. The rst nine are “historical scenarios,” meaning they are studies of the Doolittle Raid in game format, beginning with small tactical fragments and culminating with the entire mission. Scenarios 1-6 are presented chronologically to study the tactical action over the targets, incorporating only the rules of Part 1 [rule sections 1.0-4.0]. Using only an 8.5” x 11” Target Map, they are brief aairs that portray each fragment of the raid. Taken collectively, the fragments combine to present the eeting but violent mission over Japan. Each scenario includes a unique Debrieng Chart (in this book), putting its fragment into a historical context and oering a glimpse of a larger narrative. If you are new to Enemy Coast Ahead: The Doolittle Raid, Scenario 1 is a good place to start [p.5, but read pages 3-4 too].